July 13th, 2016

Running Through Life

Charity Maniates, MSPA, MPH, PA-C

The announcer calls the mass of runners, ranging in age from fourteen to ninety-one, to the starting line. The air feels suddenly stuffy and a strong waft of body odor circles; the heat from cramped bodies feels like a 95-degree day. “On your mark!” The throng of runners pushes to the starting line. The gun pierces the air and bodies spring forward, releasing invisible energy into the atmosphere. Scanning the crowd, I see my two-year-old perched in his father’s arms with his shark slippers peeping out and pacifier bobbing, pointing at me as I run by. Crushed that I did not stop to see him, he cries.

The first mile feels effortless as the runners move and breathe like a school of fish, merging in one direction. By the end of mile two, my pace settles, following the rhythm of my breath, and I resist the urge to follow the few people who pass me. Yet, my racing instinct calculates a strategy to slowly pick off runners who are waning or slowly wear them down by hovering on their heels. My body reminds me that simply holding my pace will be a challenge, as my “training” entailed fumbling out of bed at 4:30 AM to run 3 to 4 miles for the last month. Prior to motherhood, I was much more ambitious — integrating speed workouts or hill repeats, interval training, and long runs on the weekends. For now, the simple process of just running without a strategy is cathartic and satisfying.

The first mile feels effortless as the runners move and breathe like a school of fish, merging in one direction. By the end of mile two, my pace settles, following the rhythm of my breath, and I resist the urge to follow the few people who pass me. Yet, my racing instinct calculates a strategy to slowly pick off runners who are waning or slowly wear them down by hovering on their heels. My body reminds me that simply holding my pace will be a challenge, as my “training” entailed fumbling out of bed at 4:30 AM to run 3 to 4 miles for the last month. Prior to motherhood, I was much more ambitious — integrating speed workouts or hill repeats, interval training, and long runs on the weekends. For now, the simple process of just running without a strategy is cathartic and satisfying.

In the middle of mile 3, I glimpse a spry older man in his 60s, moving at a good clip just ahead. As a runner, I appreciate his smooth stride, and as a physician assistant, I’m impressed by his strength and fitness in stark contrast to patients his age recovering in rehab, unable to ambulate more than 200 feet daily. I assume that the runner I’m following is healthy because he doesn’t fit the picture of the patients I see. I think about the typical underlying reasons for my patients’ failing health — lifelong tobacco abuse, drug addiction, obesity, and alcoholism, taxing aging bodies that no longer can fight. For others, these factors are not central to their health histories, but diseases root themselves no matter how healthy one appears. One particular patient stands out in my mind — a frail man with advanced Parkinson’s disease and severe dyskinesia leaving him wheelchair-bound. Just 10 years prior to his illness, he had been an avid marathoner and, sadly, was not able to stave off the insidious course of dementia. It strikes me that the fit, older runner I’m trailing could have been a mirror image of my patient during his running days.

I keep my eyes fastened on the nameless older runner as we run the hills and he stays strong, reeling me in with his own steady pace. His gait slows at the last hill and I pass him, and for a moment, in between my labored breath and burning quadriceps, I feel as though I’ve wronged a good friend. Grateful the hills are behind me, I feel the surge of energy propelling my unsteady legs down the backside of the hill with 1 mile to go. This is when my flimsy training regimen falls short, as evidenced by my poor recovery and lack of accelerations. I’m 1/2 mile from the finish and I attempt a push, only to sputter pathetically when I approach an incline and desperately rely on my mental toughness and determination to across the finish line. A cold water is thrust into my hand. I spot the phantom runner walking to his car, looking refreshed, as though he had never run the race.

After cooling down, I scan the final posting times and am struck by the intergenerational aspect of road racing, which is unlike most sports. I have come in 6th for the 40–49 age group, which is a pleasant surprise for me. What is more impressive is the final finisher — a 91-year-old man who frequents the local road-racing circuit, defying the typical path of the aged, committed to moving and breathing until he can no longer.

This year, I entered a new age bracket in both life and road racing, shifting my fitness goals to enhance my future health and simply revel in placing one bunion-clad foot in front of the other on the road, up a mountain, or in the woods. If all goes well in the next 30 years, maybe I’ll be the one to provide inspiration to that tired mother on the race course who just wants to keep moving.

June 29th, 2016

The Specialty Shuffle

Harrison Reed, PA-C

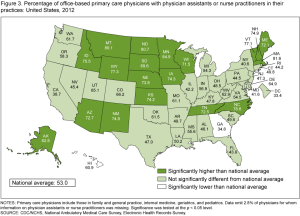

More recently, a well-meaning acquaintance told me that the PA profession was important because “most of you work in primary care, right?” While I felt the comment required some factual correction, I found my own response somewhat lacking. The actual percentage of PAs in primary care is somewhere between 20 and 30%, I told him. But I couldn’t answer the next question: why?

I could just point to physicians. After all, we do “pretty much” what they do, right? It makes sense that our specialty distribution should mirror theirs and the same factors pulling physicians away from family practice should affect PAs as well.

But it’s not that simple.

New research by Perri Morgan and colleagues published in the Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants (JAAPA) sheds light on the interplay of physician-PA specialty selection. To start, the study confirms that the proportion of PAs entering primary care is declining, from 50% in 1997 to 30% in 2013. It’s a finding that mirrors trends in other healthcare professions and by itself is not surprising.

But the authors found another correlation in their data: the positive link between PA employment and the ratio of MD-to-PA salary. If that one made you pause, it should. Of course PAs might be attracted to specialties in which we make higher salaries. But why would there be more PAs in specialties in which our physician colleagues collect bigger paychecks relative to PAs?

Perhaps the answer lies not in the supply of PAs (i.e., where we choose to practice) but in the demand for them (i.e., the number of jobs available). High-earning physicians stand to make more money when they free up time by offloading clinical tasks to PAs (like a surgeon who operates more by hiring a PA to provide post-operative care). PAs in these fields also represent a better bargain when compared to hiring another highly paid physician in the same specialty.

It might sound intuitive and straightforward, but the economics of specialty distribution are essential to understanding why a smaller proportion of PAs are entering primary care. If there really is a primary care provider shortage, one that is set to worsen in the coming decades, we should consider insights from research like the Morgan study before planning interventions.

If PA salaries rise at rates greater than those of our primary care physician colleagues, practices will reap fewer financial rewards by hiring PAs. If well-meaning incentives designed to lure PAs to underserved primary care clinics (like salary increases, bonuses, or loan repayment) drive up the average cost of a PA in primary care beyond what non-subsidized practices can afford, we may see a further decline in the overall percentage of PAs in primary care.

Of course, we have always needed a healthy supply of primary care providers and the percentage of clinicians in that field must grow as we insure more Americans and as our population ages. But the choppy seas of healthcare economics respond to legislative and financial interventions in unpredictable ways. More healthcare workforce research might help us see the waves before they come crashing down.

June 22nd, 2016

Gun Violence — A Public Health Crisis

Elizabeth Donahue, RN, MSN, NP-C

On Monday, June 13, the familiar (in the wake of the Pulse Nightclub shootings) gave me pause. I asked my first patient of the day a question I had posed to hundreds of patients before her, but on that Monday morning, I nearly spat out the words: “Do you or does anyone in your home own a gun?” Maybe I imagined it, but I could have sworn that my patient gave a slight shiver before responding with a quiet but emphatic, “No, absolutely not.”

As people who provide health care, we ask multiple emotionally charged and personal questions every day. We ask patients about their alcohol use, their sexual activity, their history of domestic abuse, their family, and all kinds of other things within the context of understanding their risks and in trying to prevent and treat physical and mental illness. But in light of the violence in Orlando and the subsequent national discussion, I found myself wondering— how many providers are posing questions about firearms to their patients?

I am trained in family medicine, and in the first two (most sleepless) years of my practice, I had the opportunity to see patients across the lifespan. I really enjoyed working with pediatric patients during this time. I cared for a lot of adolescents, who were honest and, frankly, unfiltered in a way that adults are not. It was one of those adolescent patients who put me face-to-face with the reality of what a gun can do to a human being. I saw her in follow-up of an accidental gunshot wound to her dominant hand. She matter-of-factly described the events of a night out with friends that led her to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, and whereby she became an innocent bystander in a shootout. As we monitored her course over months, her story alternated between how “lucky” she was to have sustained minimal injuries (someone else in the incident had lost their life to the same spray of bullets) and frustration at her lack of progress in recovering. She had lost significant mobility and suffered nerve damage. And the physical wounds, according to her mother and advocate, were nothing compared with her frequent nightmares and setbacks at school and socially. I felt the same empathy for her that I feel for patients who have also suffered any accident or illness that occurs randomly and causes everyone to ask, “why?”

I am trained in family medicine, and in the first two (most sleepless) years of my practice, I had the opportunity to see patients across the lifespan. I really enjoyed working with pediatric patients during this time. I cared for a lot of adolescents, who were honest and, frankly, unfiltered in a way that adults are not. It was one of those adolescent patients who put me face-to-face with the reality of what a gun can do to a human being. I saw her in follow-up of an accidental gunshot wound to her dominant hand. She matter-of-factly described the events of a night out with friends that led her to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, and whereby she became an innocent bystander in a shootout. As we monitored her course over months, her story alternated between how “lucky” she was to have sustained minimal injuries (someone else in the incident had lost their life to the same spray of bullets) and frustration at her lack of progress in recovering. She had lost significant mobility and suffered nerve damage. And the physical wounds, according to her mother and advocate, were nothing compared with her frequent nightmares and setbacks at school and socially. I felt the same empathy for her that I feel for patients who have also suffered any accident or illness that occurs randomly and causes everyone to ask, “why?”

This patient, along with all of my patients under age 18, was asked to complete a safety screening form at every annual visit that includes the question, “Do you or anyone in your home own a gun?” But what about adult patients? Likely out of habit, I have continued to screen every patient in the last 6 years for the presence of a gun in the home, and now my EMR prompts this question in a section on “social history.” Why do we ask? Because we might be able to advise a change in behavior that can prevent a dangerous outcome. When I ask a patient this question, it can prompt a discussion with those who do own a firearm. The discussion is not aimed at removing guns from their owners, but simply at ensuring that a household is safe. Sometimes a patient hasn’t thought about locking their guns, or about storing them unloaded and keeping their ammunition in a separate location. Sometimes a patient hasn’t thought about their children — about how their age and inherent curiosity can present a safety risk. Sometimes a patient hasn’t thought about the implication of owning a gun while living with a family member who has mental health issues. I believe it is my job to have these conversations — in the same way that I ask patients about seat belt use, substance abuse, contraception options, and other things that could affect their health and safety. I do not ask in order to make a judgment of the patient, but in an attempt to uncover information that could help me to best care for him or her.

I also believe that it is part of my job as a care provider to be engaged in learning and advocating about issues of health and safety. When a patient suffers from gun violence, we understand part of the “why” — pathology, forensics, etc. piece together the effects of a gunshot wound. But we don’t seem to have enough research, data, or funding to truly understand “why” on a bigger level. Because of a lack of knowledge, it is difficult to make changes or recommendations to decrease the possibility of a gun-related death or injury. The American Medical Association recently declared gun violence a public health crisis, and also declared their intent to lobby for a lifting of the ban on gun violence research imposed on the CDC. The American Nurses Association defended healthcare providers against suggested “gag rules” that would have prevented professionals from discussing gun safety with patients after the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in 2012. I support these professional organizations tasked with improving public health in their attempts to support meaningful changes that could reduce gun violence in our country.

I also believe that it is part of my job as a care provider to be engaged in learning and advocating about issues of health and safety. When a patient suffers from gun violence, we understand part of the “why” — pathology, forensics, etc. piece together the effects of a gunshot wound. But we don’t seem to have enough research, data, or funding to truly understand “why” on a bigger level. Because of a lack of knowledge, it is difficult to make changes or recommendations to decrease the possibility of a gun-related death or injury. The American Medical Association recently declared gun violence a public health crisis, and also declared their intent to lobby for a lifting of the ban on gun violence research imposed on the CDC. The American Nurses Association defended healthcare providers against suggested “gag rules” that would have prevented professionals from discussing gun safety with patients after the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in 2012. I support these professional organizations tasked with improving public health in their attempts to support meaningful changes that could reduce gun violence in our country.

In the meantime, I’ll keep asking my patients about guns in their homes and counseling them on how to be safe in the presence of guns and when to consider removing a gun from a home where there is increased risk for its unintended use.

Thus far in 2016, 6232 people have died due to gun violence. Nearly 1600 of those deaths represent children under the age of 18. Could any one of these lives lost have been saved by a conversation between a provider and a patient? I can’t answer that question, but I do think it’s worth our time to ask, just in case.

Notes and Links:

Yesterday, June 21st marked National ASK “Asking Saves Kids” Day. To learn more about this campaign designed to promote children’s safety click here:

http://www.askingsaveskids.org/

To learn more about the recent AMA position on gun violence after the Pulse Nightclub shooting click here:

http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/news/news/2016/2016-06-14-gun-violence-lobby-congress.page

To learn about ongoing discussions about funding and provider discussions regarding gun safety after the Sandy Hook Elementary School Shooting in 2012, click here:

June 16th, 2016

When Is It A Good Time to Retire?

Scott Cuyjet, RN, MSN, FNP-C

One consideration is money, of course. The longer I wait, the more income I will have per month. According to the Social Security Administration, “If your full retirement age is older than 65 (that is, you were born after 1937), you still will be able to take your benefits at age 62, but the reduction in your benefit amount will be greater than it is for people who were born before 1938 […] If you start your retirement benefits at age 62, your monthly benefit amount is reduced by about 30 percent.”

Another consideration is performance: Do I wait until I can’t do my job as well, or do I get out while I am still at the top of my game? I read an article recently that addressed this theme, but on the topic of when to stop driving. It is about seniors being in control of when they stop driving by thinking about it ahead of time and discussing it with family, in contrast with having someone else make the decision for them, which can cause embarrassment.

Another consideration is performance: Do I wait until I can’t do my job as well, or do I get out while I am still at the top of my game? I read an article recently that addressed this theme, but on the topic of when to stop driving. It is about seniors being in control of when they stop driving by thinking about it ahead of time and discussing it with family, in contrast with having someone else make the decision for them, which can cause embarrassment.

So, when is it a good time to retire? And what are the implications of this decision as a healthcare provider?

First, sometimes, we become aware that we are no longer at the top of our game, and this could affect the quality of our patient care delivery. It is one thing to forget the details of a diagnosis or treatment we rarely see, which is normal unless you are gifted with a photographic memory, but yet another to forget things that are common knowledge or routine practice for clinicians (e.g., forgetting to get a complete history, forgetting to document something you talked about with a patient, or ordering the wrong medication or the wrong dose). If our coworkers notice our performance slipping, they may or may not say anything to us or to our supervisors in order to protect us. If they do not speak up, this often forces them and others to have to compensate for us, and this can put patients at risk.

Second, according to The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, “One in every five American workers is over 65, and in 2020, one in four American workers will be over 55, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.” A mass exodus of retiring workers, who subsequently also need healthcare as an aging population, could simultaneously leave healthcare without many of its providers while adding to the load placed upon it. Older, experienced providers also frequently play important roles as leaders and mentors, and without them we may wind up with a less-experienced healthcare workforce, which could also have negative consequences for patient care.

Second, according to The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, “One in every five American workers is over 65, and in 2020, one in four American workers will be over 55, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.” A mass exodus of retiring workers, who subsequently also need healthcare as an aging population, could simultaneously leave healthcare without many of its providers while adding to the load placed upon it. Older, experienced providers also frequently play important roles as leaders and mentors, and without them we may wind up with a less-experienced healthcare workforce, which could also have negative consequences for patient care.

Retirement does not have to mean stagnation. With some planning, a healthcare provider could do something that utilizes a different skill set, such as teaching. We could also go back to school to learn a new skill. Another temporary option, which I have chosen recently for myself, is to simply cut back on the amount of work time. I went from working a 5-day week at 100% to a 4-day week at 80%, and this may help keep me going for a few more years while I think about my options. In the end, I think a little planning can make for a smoother transition, as opposed to waiting for life to give us a swift kick in the gluteus.

If you have any advice on how to know when it’s time to retire, as a healthcare provider or otherwise, and how to do it gracefully, I’d appreciate your comments.

June 8th, 2016

The Fringe: Part 3 – Deciphering Your Benefits Package

Bianca Belcher, MPH, PA-C

- Does your employer offer life insurance and if so, how much is the policy worth and how much do you pay for it?

- Does your employer offer short term disability and if so, what percentage of your salary does it cover? Is it a pre- or post-tax payout?

Out of 15 people, only 2 were able to answer yes/no with confidence. Most “thought” they had checked off a box at some point for life insurance and disability, but were unable to discuss the details of either. A little knowledge and forethought with these topics can go a long way if something bad were to ever happen.

Short-term disability

Short-term disability (STD) is insurance that pays you a percentage of your salary if you were to become temporarily disabled for a short period of time. If you are talking about a long period of time (usually > 3 months), you’ll need long-term disability. A few of the most common claims for STD are pregnancy, back pain, and digestive disorders, but as you can imagine – the possibilities are endless. If you think about it, you and your ability to earn income are your biggest asset.

If you are disabled and use your STD, your employer will pay you a percentage of your salary (usually 50-60%) after a waiting period of 90-180 days. Things for you to consider:

If you are disabled and use your STD, your employer will pay you a percentage of your salary (usually 50-60%) after a waiting period of 90-180 days. Things for you to consider:

- Get a running total of your monthly expenses. You should split them into two categories (Essential and Non-Essential). The Essential column should contain all expenses that you absolutely need to pay – rent, monthly medications, heat, water, car, etc. The Non-Essential list should include everything else that you spend money on that makes you happy, but you could probably live without – cell phone, expensive gym or country club membership, annual vacation to the Caribbean, Starbuck every morning, etc. Be diligent and try to include everything. The point is to give you an idea if a regular STD plan would cover you and what you’d have to sacrifice during that time.

- Ask your employer if your STD is paid out PRE or POST tax. If your employer pays you 60% of your salary and then you have to pay income taxes on that, your take home will be much less than if you receive 60% after the taxes have been taken out.

- Are you covered for YOUR profession? Many of the less expensive policies cover you for ANY profession. This means that if you are a surgical PA and lose two fingers you probably wouldn’t be able to work as a surgical PA anymore, but you could flip burgers at the local diner (meaning you can still work doing something). Because you can still work, they could deny/cut off your disability payments. This is problematic since the income potential for a surgical PA versus a diner line cook is substantially different. Conversely, if you are covered under YOUR profession (a surgical PA), if you can no longer work as a surgical PA anymore, then you can get disability based on your earnings as a surgical PA. Specialized disability insurance is a little more expensive, but depending on your salary – it might just be worth it.

- What if your employer coverage isn’t adequate? See a professional group specializing in this about a “bolt-on” or “stand-alone” policy to augment or replace your benefit from your job. Typically a bolt-on policy can get close to 85% of your base salary. These policies can grow with your career, so getting them early can be a smart, flexible decision.

Life Insurance

Life insurance is tricky and can depend significantly on your personal circumstances. Here are the basics:

- Know what your employer provides. A standard employment package likely includes 1X or 2X your salary for free with an option to purchase additional coverage at a very low rate.

- Think about why you may (or may not) need additional life insurance. Do you have children, spouse, or other dependents? Do you have debt (mortgage, student loans with co-signers, or a business)? Do you want to provide for your family in the event of your death? If you answered “yes” to any of the above, you may consider an additional policy. For a young, healthy individual, life insurance can be very affordable.

Company Match

Take a look at the retirement section of your benefits. Many companies offer a match. This means that if you put a certain percentage of your salary into retirement at work, the company will “match” that money up to a certain percent or dollar amount. To be clear, the company is giving you money to participate in the retirement plan. The folks at Highland Financial recommend contributing (at a minimum) the match-maximum to take full advantage of the greatest amount of money that the company will give you for participating.

Take a look at the retirement section of your benefits. Many companies offer a match. This means that if you put a certain percentage of your salary into retirement at work, the company will “match” that money up to a certain percent or dollar amount. To be clear, the company is giving you money to participate in the retirement plan. The folks at Highland Financial recommend contributing (at a minimum) the match-maximum to take full advantage of the greatest amount of money that the company will give you for participating.

For example, if your company will match your contributions up to 3%, make sure that you are at least putting 3% of your salary into the retirement fund. It will be as though you are putting 6% in there each year. This is a great perk and can sometimes be the differentiator between two similar job offers. In the rare case you spend your career with a single employer, those choices can make a tremendous difference.

Reimbursement

Reimbursement categories can add up to a significant amount of money. Be sure to take advantage of every opportunity possible.

- Relocation – If you are moving across the country, it can be very expensive ($2,000-$10,000).

- Professional Licensure/Certification/State Controlled Substance/DEA- The first time around, these costs are about $1,500 for PAs (this varies for MDs and NPs); after that the fees tend to spread out – some are annual, while others are every 3 years.

- CME events/conferences – You need continuing medical education in order to maintain your license. If you are at a large academic institution, you probably can’t walk down the hall without tripping over a free CME opportunity, but if you are at a private practice or smaller hospital, this reimbursement will be crucial. To put things into perspective, $1,500-2,000 usually covers 1 conference after adding up conference fees, flight, hotel, and food.

Hope this was helpful. The Fringe: Part 4, the last installment, will address retirement — a subject that becomes more interesting the older we get, but should be considered important by providers early in their career as well.

A special thank you to Michael Franchella, financial expert specializing in medical professionals, and Highland Financial Group for their wisdom and expertise with much of the above content.

June 3rd, 2016

The Sound of Silence

Charity Maniates, MSPA, MPH, PA-C

Why is this trend happening? It’s multifactorial, as we say in medicine. Unsafe living environments, decreased functionality, frailty, advancing dementia, and progressive disease all contribute. Yet perhaps the primary reason— one that if addressed could reduce this challenge substantially — is poor communication between providers and patients and their families during the early stages of illness, when a dialogue should occur about goals of care, especially when a serious or advancing illness is experienced. Over the course of advancing illness, often the prognosis is not clear to the patient and family, leading to unrealistic expectations or unsuccessful recovery. Additionally, when end-of-life care wishes are not voiced or appear clouded, extensive workups that do not improve quality of life occur. Consequently, care is reactive every time an exacerbation recurs or symptoms worsen, resulting in unnecessary prolonged suffering or, worse, dying in a hospital bed rather than quietly at home.

The simple solution is to initiate clear conversations at early stages of serious illness. However, on the whole, this discussion does not come easily or naturally to medical providers. After all, we are trained to diagnose and treat disease and save lives; robust training in palliative care and end-of-life care is scant. Faced with office visit time constraints or patients lost to follow-up, providers may not feel they have the time or the ability to engage patients in a delicate conversation. Consequently, providers avoid broaching the topic and resort to what we are comfortable with: tests, medical jargon, and workups. For many patients, a robust conversation about their illness occurs after multiple hospitalizations, triggering a palliative care consult. In an ideal approach, the entire medical community should take responsibility as a whole to engage a patient in assessing the understanding of their illness and prognosis. In the long term, being proactive will reduce futile readmissions and, most importantly, honor the wishes of patients when end of life is near.

Working in geriatrics and skilled nursing facilities, I frequently engage in conversations about goals of care, and many times I have left a patient’s room feeling frustrated that a resolution or next step was not reached. Recently, I attended a training on engaging a patient in a “serious illness conversation” and learned that with some practice, a provider can engage in an effective 20-minute serious illness conversation, according to an evidence-based guide developed by Harvard Medical School Center for Palliative Care and Ariadne Labs.

The trainers highlighted that a serious illness conversation is evolving and touched upon numerous times as illness or symptoms change. A concrete resolution or action may NOT be reached during a conversation, which was an epiphany for me. (Really, how can we expect every patient to have concrete answers or acceptance of their illness during one conversation?) Time is often needed to assimilate information, reflect, and talk with loved ones.

A significant proportion of the conversation guide focuses on sharing and exploring prognosis. When sharing prognosis (surprisingly, the most overlooked and avoided topic for medical providers), allowing silence and then exploring the emotion of the patient is key. This is harder than one would expect. During the training, I role-played sharing a prognosis with a stoic patient. I allowed for silence — a short, uncomfortable, three-second silence. Feedback from observers was that I rushed to provide information too quickly, not allowing the patient enough time to ask questions or process. Utilizing a conversation guide helps to ensure vital components surrounding prognosis are addressed including: important goals, fears, worries, and how much a patient is willing to go through for the possibility of more time. Once comfort is achieved with the flow of conversation, tailoring for each patient becomes much easier.

What drives me to continue to cultivate my “serious illness conversation” is the positive response I have received from patients when conversations have gone well. I recall a family member crying on the phone, thanking me for bringing up the topic because she didn’t know how to. In another, a patient in rehab with end-stage cardiomyopathy was failing and desperately wanted to go home. Hospice care was initiated at her discharge, and three days later, the patient’s sister called me, overwhelmed with gratitude that she had passed peacefully at home, fulfilling her last wish. (My only wish was that it had been six months earlier.) These are moments that fill me with passion and fulfillment for the work I do.

The next time you have a visit with a patient with a serious illness, resist the urge to brush over “that topic.” Don’t assume that the next provider will bring it up, because most likely they won’t. Simply ask the patient if they are open to talking about their illness and how things are going. This straightforward invitation to delve into a gray area of medicine, rather than offering a procedure or test, can be more powerful to your patient than you know.

May 25th, 2016

The Book and The Novelty

Harrison Reed, PA-C

Friedel rocked the chess world when he created Chessbase, a computerized database that catalogued every single game of chess ever played. This stockpile of chess history not only recorded the individual moves of every match, it revealed an embarrassing truth: even the grandmasters rely on heavy repetition.

In chess, there are a finite number of opening moves. No matter which one a player selects, it has been played millions of times in prior games. The second move, no matter what, will also look familiar from some fraction of those previous games. The same holds true for the third and the fourth and the fifth, each to a smaller degree. While the number of prior identical games will decrease with each subsequent turn, the fact remains that someone, somewhere, has played the exact combination of moves before. The best players in the world can exchange pieces for hours without ever featuring an original combination of moves.

The massive collection of known chess board positions is known as “The Book.” Many moves in The Book are so well known in chess circles that grandmasters can play portions of a game from strict memory, without any original thought or tactic. With such well-documented and rehearsed strategy, you might wonder why chess fanatics even bother with the game at all.

The massive collection of known chess board positions is known as “The Book.” Many moves in The Book are so well known in chess circles that grandmasters can play portions of a game from strict memory, without any original thought or tactic. With such well-documented and rehearsed strategy, you might wonder why chess fanatics even bother with the game at all.

But there is a special moment that happens in nearly every chess match. As two players locked in battle lunge and parry, feign and circle, they stray further and further from the routine and predictable setups. And then, in a single move, the players find themselves in a situation that is utterly unique, never before concocted in a prior match. From that point on, the players have no road map, no blueprint. The game is pure creation.

That moment is known as The Novelty. And it is the reason people play the game.

Of course, medicine has a Book, too. Heck, medicine has a whole library of Books. The amount of established medical knowledge now doubles at an alarming rate. And with each large clinical trial or new set of recommendations from expert organizations, the known moves in medicine become a little more established. Sometimes it seems even the grandmasters of medicine can just play from memory.

But medicine has a complexity that chess never will. We don’t play on a fixed wooden board with the same set of pieces. We practice at the intersection of a unique patient and a dynamic world. It is great to know the Book, but it is even better to know when to make a different move, when the rules do not apply, when to break convention.

Today’s version of medicine may feel like speed chess, with pieces slammed down with as much regard to the time on the clock as the position on the board. But every patient’s story has a little wrinkle that makes it different. That requires us to always be prepared to make a move for the sole benefit of that individual. That is The Novelty.

And it is the reason we play the game.

May 18th, 2016

The Nurse In Me

Elizabeth Donahue, RN, MSN, NP-C

While there is plenty to celebrate during Nurses Week, including but not limited to care provided, research led, innovations generated, and compassion demonstrated by nurses, it is also a time for reflection. What is nursing? Why did I choose it and what does it mean to me?

As a nurse practitioner, I am frequently caught between the worlds of nursing and medicine. I have the educational foundation and roots of a nurse. And yet, in my advanced practice role, I spend my time as a provider akin to my physician colleagues — assessing, diagnosing and planning for treatment. I often notice that I am feeling the strain of straddling two worlds — trying fervently not to let go of the identity that shaped me, but acknowledging that my role has changed and seeking to fit into a new reality. Not only that, but I have spent a significant amount of time defending my position in this provider world — touting my advanced training and independent licensing, my experience and my ability — and aiming to find my place, one that is respected and welcome. I imagine it’s not unlike what an immigrant to a new country feels like — identifying with and cherishing the traditions of their home while trying to assimilate to the culture in which they find themselves. Thankfully, that is not a struggle that I have ever had to endure, but one I know well from the stories of my patients and through many immigrants I have encountered through volunteer work.

As a nurse practitioner, I am frequently caught between the worlds of nursing and medicine. I have the educational foundation and roots of a nurse. And yet, in my advanced practice role, I spend my time as a provider akin to my physician colleagues — assessing, diagnosing and planning for treatment. I often notice that I am feeling the strain of straddling two worlds — trying fervently not to let go of the identity that shaped me, but acknowledging that my role has changed and seeking to fit into a new reality. Not only that, but I have spent a significant amount of time defending my position in this provider world — touting my advanced training and independent licensing, my experience and my ability — and aiming to find my place, one that is respected and welcome. I imagine it’s not unlike what an immigrant to a new country feels like — identifying with and cherishing the traditions of their home while trying to assimilate to the culture in which they find themselves. Thankfully, that is not a struggle that I have ever had to endure, but one I know well from the stories of my patients and through many immigrants I have encountered through volunteer work.

During the day-to-day provision of care, I find that it can be easy to let the nurse in me fade into the background while I wear my provider “hat.” I practice under the same conditions as my physician colleagues, that of shorter appointment slots than might be ideal, the pressure to enroll a certain number of new patients or meet an RVU target, the foreboding knowledge of the notes left to document or phone calls to return. It is all too natural to reduce the patients themselves to diagnoses waiting to be uncovered, chronic diseases needing management, checklists or tasks to be completed. I see this strain among the staff across disciplines in primary care — the front desk managing one more phone call, the medical assistants being asked to take on one more initiative, etc. By doing this, we can lose sight of the purpose of our work.

Thankfully, during the times when I have reached this lowest low of looking at patients as parts, the universe intervenes, and I am reminded of the “nurse” included in my title. Recently, a patient reflected on her visit, noting that she felt that something about her care was different. The way I explained her condition and instructed her made it seem easier to attain her goal. She said “maybe it’s because you are a nurse.” And I thought, yes, perhaps it is – because I am. Lately, as part of an initiative by our hospital nursing department, each day I receive an email with a reflection/reminder to practice in the way that nurse theorist Jean Watson intended when she scribed her “Philosophy and Science of Caring.” It has served as a daily reminder. When I am returned to my nursing roots, I am a better provider. I see the patient as a person again. I focus on their needs and their abilities. I realize that this endeavor toward health works better when patients see that I care and that I am their partner. I recognize the import of cura personalis, Latin for “care for the entire person,” a value stressed in my Jesuit education. I embrace the core values of caring, integrity, and excellence. And I can model this patient-centered attitude for all of my colleagues.

I am grateful to be a part of this wonderful profession called nursing. And I wish to use this Nurses Week to remind anyone in healthcare that we can better serve our patients when we truly view them and care for them as people. “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts,” per Aristotle; may we be cognizant of this principle not just during this special week but during all of those that come before and after it.

May 4th, 2016

The Fringe: Part 2 – Debt Management

Bianca Belcher, MPH, PA-C

So many students come out of medical school, PA school, or nursing school with a significant amount of debt. Couple graduate loans with undergraduate loans and/or other loans that you may have taken on over the years (car, house, etc.) — and the final number can be scary.

I had the opportunity to sit down with a financial expert, Keith Gilbreath from the Highland Financial Group, who specializes in financial management for medical professionals and he was able to present five very relevant tips to help with debt management.

TIP #1: Organize your student loans by interest rate. Focus on paying off the highest interest rate loans first.

| Who You Owe | Loan Amount | Interest Rate | Monthly Payment | Ranking |

| Lender A | 25,000 | 5.25% | $200 | 2 |

| Lender B | 20,000 | 3.50% | $150 | 4 |

| Lender C | 22,000 | 5% | $165 | 3 |

| Lender D | 15,000 | 7.90% | $125 | 1 |

Sit down and list out all of your loans, their amounts, interest rates, and monthly payments. Add a final column entitled Ranking. Run-through all of your loans and rank them according to interest rate (Highest = 1). Focus on paying off your highest interest rate loans first. According to the example above you would focus on paying off Lender D first. So, in addition to the monthly payment, you should try to pay extra per month just toward that loan as opposed to the group of loans. Once you pay it off, you then can take that $125 per month payment (that you are used to paying already) and add it as an “extra” payment for Lender A (Rank #2) and so on and so forth.

TIP #2: Consider Consolidation. When possible, a simplified payment to a singular entity (at a low interest rate) always trumps multiple payments to a bevy of providers. New private providers (big banks) focus on debt repayment every few months. Keep an eye out for great interest rates and consolidation deals, even if it is just for the highest interest rate debt that you have. If you qualify, it could save you thousands in the long run!

TIP #3: Pace Yourself. Although paying off loans is very important, don’t forget about the other things in your financial life that need attention – like retirement!

TIP #4: Create Automatic Payments. Debt and revolving credit often carry penalties for late or missed payments. Set yourself up for success by scheduling automatic payments and chip away at those balances worry free. In addition, some lenders even offer a reduction in interest rates if you sign up for automatic payments.

TIP #5: Review you balance(s) periodically. Everyone likes success and while you may groan at the sight of your remaining balance, remember: 1) where you started, and, 2) that you are headed in the right direction! Progress should always be celebrated.

In the upcoming part 3 of “The Fringe” series, we will discuss deciphering your benefits package.

; [/php]/images/AU000_cmaniates.jpg)

; [/php]/images/AU000_hreed.jpg)

; [/php]/images/AU000_edonahue.jpg)

; [/php]/images/AU000_scuyjet.jpg)

; [/php]/images/AU000_bbelcher.jpg)