May 5th, 2014

Physical Activity Improves Heart Rate Variability In The Elderly

Larry Husten, PHD

A new study in Circulation offers fresh evidence that physical activity is beneficial to the heart in people aged 65 and older. Benefits were observed both in elderly people who reported the highest amount of overall physical activity and in those who increased their physical activity over time.

U.S. researchers evaluated heart rate variability (HRV) using serial 24-hour Holter monitoring in 985 older adults over a 5-year period. They found that greater total leisure-time activity, walking distance, and walking pace were each associated with more favorable HRV indices. HRV has been previously shown to predict cardiac risk.

Increased physical activity was also associated with additional measures of improved cardiovascular risk, including a healthier circadian pattern. Any physical activity “is better than none, and more is better,” write the authors. The results were consistent with previous studies in younger populations.

May 5th, 2014

Two Experts Look at a Failed HDL Trial

William Edward Boden, MD and Prediman K Shah, MD

Despite robust epidemiological evidence suggesting that HDL has a strong protective effect against cardiovascular disease, there has been no good evidence showing that HDL-based therapies are beneficial. Now, the CHI-SQUARE (Can HDL Infusions Significantly QUicken Atherosclerosis Regression) study, published online in the European Heart Journal and the largest to ever study an HDL mimetic, has failed to find even a glimmer of benefit.

Within two weeks of having an acute coronary syndrome, 507 patients were randomized to receive 6 weekly infusions of either placebo or 1 of 3 doses of CER-001, an HDL mimetic from Cerenis Therapeutics. CER-001 had no significant effect on atherosclerosis, as assessed by both intravascular ultrasonography (IVUS) and quantitative coronary angiography (QCA). There were also no significant differences in the number of patients who had at least one major cardiovascular event.

CardioExchange asked William Boden and Prediman (PK) Shah to comment on CHI-SQUARE. — Larry Husten

William Boden, who is PI of the NIH’s AIM-HIGH trial, was asked whether it was time to write the obituary for HDL:

Boden: You have to be kidding me! The end of what? HDL RIP? How about: RIP suboptimal study design and trial hypotheses? I continue to be amazed that we see nothing but pejorative commentary and noise about the death knell for the HDL hypothesis and HDL-raising therapy when, time after time and trial after trial, we see the same unenlightened study design perpetuated.

What do ILLUMINATE, dal-OUTCOMES, HPS-2 THRIVE, and this CHI-SQUARE trial all have in common? The answer is: an unreasonable study population in which to test HDL-raising therapy. The two CETP inhibitor trials and this one included ACS patients who were not pre-selected for a profile of low HDL-C cholesterol. In fact, I did not see any baseline lipid value for CHI-SQUARE. The baseline Apo-B values were <80 mg/dL in two groups and were 81 and 86 in the other two group0s — values that would be considered “optimal” or ideal. The Apo-A1 values of >130 mg/dL are likewise normal. Hence, we can presume that the baseline LDL-C and HDL-C were normal, or perhaps optimal. Why on earth would one expect a patient with an HDL-C of, say, 50 mg/dL to demonstrate a reduction in coronary atherosclerosis or clinical events when you are making a normal baseline value super-normal with an HDL-raising intervention? Since the epidemiology of HDL-C tells us that the risk of incident CV events is both inverse and curvilinear, if the starting HDL-C is on the flat (normal) part of the event relationship, then why would one expect that raising the HDL-C to 70 or 80 would reduce CV events?

Our recent data (from four separate sources of observational and post hoc RCTs) suggest that baseline HDL-C <30 mg/dL may be the threshold below which one needs to target HDL-raising therapy. This is where the event curve steepens inversely and where one might expect to see an HDL-raising therapeutic benefit.

So this trial tells me nothing new that I haven’t seen in the other trials I’ve mentioned. In our post hoc analysis of AIM-HIGH (admittedly only “hypothesis-generating”) an HDL-C <31 mg/dL was associated with a niacin treatment effect for the primary endpoint. This would actually be the fifth data set to show that it’s the very low HDL-C subset that we need to target, not these “all-comers” designs where patients have normal or high HDL-C to start.

We have yet to see the right trial design. And, of course, since the great majority of AIM-HIGH and HPS-2 patients were receiving statins for 1-5 years, how can you expect, as in HPS-2, to see an incremental HDL-C raising effect when the baseline LDL-C was 63 mg/dL and the baseline HDL-C was ~47 mg/dL? Maybe we need trials of patients who are statin naïve, not such well-treated patients where risk mitigation perhaps cannot be achieved.

PK Shah is the Director of the Atherosclerosis Prevention and Treatment Center and of the Oppenheimer Atherosclerosis Research Center at Cedars-Sinai, he holds the Shapell and Webb Family Chair in Clinical Cardiology, and is a Professor of Medicine and Cardiology.

Shah: This is a very disappointing study showing no short-term effects of rHDL (containing wild type Apo A-I linked to two phospholipid carriers) infusion at doses of 3, 6, 12 mg /kg on non-culprit coronary lesion size as assessed by IVUS and QCA.

If you are a pessimist and disregard all the biological plausibility data on the vascular protective effects of Apo A-I or its mutants, such as Apo A-I Milano shown in preclinical models and small clinical studies, you could conclude that Apo A-I infusions therapy may not realize its promise; on the other hand, if you are an optimist, you could make the argument that a negative study could have been due to:

1. Not measuring plaque composition, which is more likely to change before plaque size changes; i.e., not measuring lipid core size and the inflammation that goes with it. IVUS may not be the best methodology.

2. Not choosing the type of patient most likely to show a change in plaque; i.e., a patient with a lipid-rich plaque rather than any plaque without regard to its composition.

3. Not using a high enough dose (the Apo Milano study in 2003 used 15 and 45 mg/kg/per dose while as doses used in this study were 3, 6, 12 mg/kg/dose).

4. Not using enough infusions to remodel the plaque.

5. The compositional features of the HDL mimetic used in this study may not be optimal; HDL containing Apo A-I Milano, possibly a gain of function mutant, may produce different results as suggested by preclinical studies done in our laboratory.

As a believer in HDL’s vascular protective effects, I remain optimistic that, although HDL has been a tough nut to crack, one of these days we will get it right using the right formulation, right patient, and right dose; research in this field must continue until we get it right, the basic biology is very compelling.

May 5th, 2014

What Role Should Coca-Cola Play in Obesity Research?

Larry Husten, PHD

What role should Coca-Cola and other food and beverage companies play in funding and communicating research about nutrition and obesity?

The question is prompted by a recent article in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology. The “state-of-the-art” paper reviews the relationship of obesity and cardiovascular disease and presents the case that a decline in physical activity is the primary cause of the obesity epidemic. The article downplays the role of calories and diet and does not include the words “sugar,” “soda,” or “beverage.” Three of the five authors of the paper report financial relationships with Coca-Cola.

It is important to acknowledge that there is an active scientific controversy about the relative importance of diet and exercise. But it also seems clear that the perspective on this controversy as presented in this paper is remarkably congruent with the interests of Coca-Cola.

Defending Coca-Cola

I asked the lead author of the paper, Carl Lavie, a Louisiana cardiologist and obesity expert, to respond to concerns that the authors’ relationships to Coke may have affected the content of the paper. Here is Lavie’s (lightly edited) response:

My personal relationship was providing consulting and giving a couple of lectures on the importance of fitness. My colleagues have also consulted and received non-restricted educational grants for research studies. Coca-Cola had nothing to do with the details of the study, analyzing results, or publishing the paper. Therefore, I do not think that this relationship adversely impacts any of the results of their studies or my invited state-of-the-art review article, which happens to be on a topic where I have published more than anyone else in the world during the past 10-15 years.

My article really was not on sugar, and you are correct that this (or diet in general) was only briefly mentioned. Although there is a lot of attention on fast foods and sugary beverages causing obesity, the research from my colleagues and I show that very marked declines in physical activity, which is also a major component in leading to fitness, is by far the major cause of obesity, not sugar and fast foods. Nevertheless, I agree if the physical activity is very low, one must cut all calories to compensate, including those from sugar and fast foods. Regarding Coca-Cola, although their “flagship” product is a sugary beverage, keep in mind that they have many more low or no calorie products in their comprehensive arsenal!!

In the medical field, many companies fund studies and educational programs, but the investigators and speakers are not changing what they say due to who sponsors the work!”

Lavie subsequently sent a succinct summary of his position:

1) Hopefully the science speaks for itself, regardless of the sponsor.

2) Science itself is improved by data and facts.

3) Not to be too harsh, but my opinion (based on my interpretation of the science) is not for sale and cannot be bought. I am sure my colleagues feel the same way.

4) All researchers have bias, as do I, but if you try to eliminate every researcher/scientist/clinician with bias, there will be hardly any left.

5) Therefore, the best way to proceed is to focus on well-designed and well-executed studies.”

I then sent Lavie some followup questions:

Do you believe there should be any limitation on industry funding of research and education? What about research sponsored by a tobacco company?

Lavie: I do not think so, as long as it is fully disclosed. I believe that in some of the tobacco settlements they are having to pay money for research. There are very little potential health benefits of tobacco, although I guess if one smoked one cigarette a week there may not be much harm. I personally have no problem with [some]one accepting funds, particularly as a non-restricted educational grant, but suspect few would do so considering the negative feelings that so many have about the tobacco industry. I suspect that very few feel as strongly about Coca-Cola, Pepsi cola, McDonalds, Burger King, Taco Bell, etc.

What about unconscious bias or subtle bias? For instance, isn’t it possible that the paper would have contained a brief discussion of sugar and sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) without the financial associations of the authors with Coke?

Lavie: This is possible I guess if one were working for a company, but in my case for example, receiving a few minor honorarium would hardly taint my views. My first lecture for Coca-Cola was just a couple of years ago, and I have been publishing on this topic for nearly 15 years, so this is probably not applicable. I have never published on sugar or even related to this in any of my nearly 800 publications, so personally this really does not apply much…

What do you think is Coca-Cola’s motivation in providing funds for research and education? Does this represent altruism on the company’s part? Would it be likely to fund researchers who hold opinions that are less congenial to their business?

Lavie: I think that they want to provide a public service that is good for their image. Also, I believe that at least many in such a company want to learn the scientific truth. I would suspect that they know that some of the studies they fund may come out neutral or even negative for their products. It would be reasonable to think that they would not want to fund someone who is viciously attacking them, but I would believe they would still fund a good, honest scientist who did a study that found some negative effect of one of their products. Pharma does this all the time. They fund studies that are stopped due to toxicity or have negative findings. Also, good drugs have adverse effects in some, and sometimes many have adverse effects and still the negatives may not outweigh the pros.

What are your thoughts about Coke (and other companies) having financial relationships with health organizations like the ACC and the AHA? How would the objectivity of these organizations be affected by these relationships in regard to public policy advocacy, such as sodas in school or a tax on SSBs? And to push this question: Should organizations like these accept support from tobacco companies?

Lavie: As long as it is all out in the open, I do not believe that the ACC or AHA would sell their scientific statements. Also, the money they would accept would have no strings attached and be for educational purposes. The AHA is not going to endorse or not endorse products based on their funding source, and I am sure the AHA/ACC would be happy to get funds from Pepsi and many of the fast food chains, who also have some “healthier choices” compared to others. McDonalds and Taco Bell are not the cause of the obesity epidemic, lack of physical activity is. I suspect that these organizations may feel uncomfortable taking funds from the tobacco industry, but I am personally okay as long as it is disclosed. If the tobacco companies, which clearly cause adverse health outcomes, provide funds from their profits that in some ways lead to promotion of better health, why would this be a bad thing?

May 5th, 2014

FDA Comes Out Against Aspirin for Primary Prevention

Larry Husten, PHD

In the latest development in a long-simmering debate, the FDA has announced that aspirin should not be marketed for primary prevention for heart attack or stroke. The announcement follows the FDA’s rejection on Friday of Bayer Healthcare’s decade-old petition requesting approval of a primary prevention indication. [PDF of FDA rejection letter]

Aspirin is still widely used for primary prevention. Many physicians, including cardiologists, recommend it for some of their patients. The American Heart Association currently supports the use of aspirin for primary prevention when recommended by a physician in high-risk patients. (There is widespread agreement that for secondary prevention the benefits of aspirin outweigh the risks and should be used to prevent a second heart attack or stroke after an earlier cardiovascular event.)

In its statement the FDA said it had “reviewed the available data and does not believe the evidence supports the general use of aspirin for primary prevention of a heart attack or stroke. In fact, there are serious risks associated with the use of aspirin, including increased risk of bleeding in the stomach and brain…” The FDA reaffirmed the use of aspirin in secondary prevention.

Cardiologist Sanjay Kaul, who often serves as an FDA consultant and advisory committee member, offered the following comment:

There have been nine primary prevention trials evaluating the role of aspirin in CVD. Not a single trial has been positive so far. When the data are pooled together in a meta-analysis, there is a small, but statistically significant, benefit which is counterbalanced by an equally small, but statistically significant, risk of bleeding. On balance, the totality of evidence does not yield a favorable benefit-risk ratio for aspirin in primary prevention. The FDA declined to approve aspirin for primary prevention in 2003. Overall, I agree with the FDA’s stance. The tough task ahead for professional societies is to acknowledge the tepid evidentiary support for their guideline recommendations. Equally challenging a task is that patients will have to recalibrate their opinions about aspirin for primary prevention of CVD.”

May 2nd, 2014

A New Tool to Discuss Primary Prevention with a Statin with Patients: Life Expectancy Gain

Darrel P Francis, MD FRCP

A new Circulation study explores the spectrum of individual medication disutility for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in a sample of the general population, and juxtaposes it against the spectrum of expected longevity gain from initiation of statin therapy. Authors Darrel Francis, Professor of Cardiology at the National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, and Judith Finegold, Clinical PhD trainee in Cardiology, put the study’s findings into perspective for CardioExchange.

When we advise a patient on primary prevention of CVD we face a paradox. Current primary prevention practice recommends starting therapy largely based on cardiovascular risk. As age increases, annual risk goes up, which guideline convention interprets as increasing reason to initiate cardiovascular prevention (e.g., with statins). Taking this reasoning to its logical conclusion, however, initiation of statins would become mandatory in all of the very elderly. Practicing clinicians may feel uncomfortable with that concept.

There are two possibly unhelpful features of our current formal processes for deciding whether to recommend treatment with (for example) statins:

1. We judge the utility of initiating statin therapy, for life, based on artificially short time windows (e.g., 10 years), rather than examining lifetime benefit in terms of lifespan gain.

2. We assume that patients will universally consider prevention to be so desirable that it would always offset the inconvenience of having to take daily medication for life.

In our recently published study we present a new way of thinking about the pros and cons of cardiovascular primary prevention, and we propose two changes:

1. Estimate the benefit (utility) in terms of increase in life expectancy.

In our study we calculate not cardiovascular risk but life expectancy (i.e., lifespan) gain from a primary prevention intervention such as a statin (Figure 1). The pattern of life expectancy gain seems at first familiar, with increasing blood pressure and cholesterol associated with higher values (redder colors), but it has one crucial difference: Cardiovascular risk increases with increasing age, but life expectancy gain from statin initiation reduces with age of initiation. Initiating a lifetime of statins adds more to life expectancy if it is done earlier than later.

Figure 1. Distinction between cardiovascular risk and life expectancy gain. Both increase with increasing cholesterol and increasing blood pressure; but while risk (left panel) increases with age, the life expectancy gain from initiating a lifetime of preventative therapy (right panel) decreases with age. (The right panel is a simplified version of a chart in our paper, Fontana et al, Circulation 2014.)

2. Assess the patient’s willingness to take even an idealized medication to increase life expectancy: you might be surprised.

Population health policies have been based on the assumption that most people do not mind taking medication to increase their life expectancy, and, if patients do mind, this displeasure (called “disutility”) is so small as to be negligible compared to the financial cost of statins. However, with patent expiry, the financial cost of statins has fallen to near zero, so cost-effectiveness analyses can no longer afford to assume that disutility is zero or near-zero in everyone.

There are many reasons for not wanting to be on medication. We wanted to determine the lower limit on disutility in each subject, i.e., the disutility in an idealized situation where these main reasons are artificially removed. Real-world disutility is likely to be higher than that (but cannot be lower). We asked respondents to imagine a tablet treatment that had (a) no side effects, (b) no significant cost to them, (c) no requirement to visit a doctor, and (d) no consequences (apart from corresponding partial loss of benefit) of missing doses or stopping and restarting treatment at will.

Our study surveyed the general public. It found that, while there are many people who would be happy to take such an idealized medication for a small increase in life expectancy, there are also many who would do so only if the life expectancy increase was large. In fact, there is a substantial group who would not take daily medication even if it gave them 10 extra years of lifespan.

Figure 2. Juxtaposition of distribution of disutility (dislike of taking regular medication, upper panel) against distribution of utility (life expectancy gain from taking a statin, lower panel) in the general population. For patients with low disutility (green), regardless of their level of risk factors (and therefore utility) it appears rational to take preventative medication. For patients with high disutility (red), regardless of their level of risk factors, disutility seems to exceed utility. For the patients in between (the grey zone), the net effect of utility and disutility depends on their individual level of risk factors. Expressing both utility and disutility on a common scale, of extra life expectancy obtained or demanded, permits them to be juxtaposed easily and discussed openly. Redrawn from data in our paper, Fontana et al, Circulation 2014.

Our study indicates that there may be many patients whose dislike of daily medication may exceed the benefit delivered by statins. This becomes easy to see when both are expressed in common units such as lifespan gain.

It should be remembered that we have assessed only a lower limit on real-world disutility. We specifically asked respondents to assume there were no side effects. We did this to set aside the public controversy on whether statins do frequently cause side effects. A recent study from our group has examined the randomized blinded trial evidence on symptoms reported on statins versus on placebo, where both groups are given the same background information and same level of inquiry regarding symptoms. It found that under these blinded conditions there is very little difference between groups (i.e., very little incremental effect of statins). This information may at first seem difficult to believe when symptoms (such as muscle ache) are so common in daily primary prevention practice. However, the key message is not that the symptoms do not occur with statins, but rather that they occur equally on placebo when patients undergo the same level of questioning with neither the patient nor doctor knowing whether they are taking the real statin.

This calculation is not universally accepted because not everyone agrees that randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled data are the most reliable way to detect genuine mechanistic causation from other phenomena, as we have seen in the recent commotion over renal denervation . The powerful risk of bias from prior belief arising from our unblinded daily experience is all the more reason to seek out blinded data.

A new way to support primary prevention consultations?

Taken together, both our current and recent studies offer options for better-informed and more individualized consultations:

1. Doctors can now show patients charts that convey benefit of statin intervention in a readily understood language: that of life expectancy gain.

2. Doctors and patients now have reliable information on side effects, coming from 80,000 patients in blinded randomized controlled trials of statin versus placebo.

3. Patients can express their individual level of dislike of taking lifelong medication using the same metric (lifespan gain) as used to express benefit.

Ultimately, patients must make their own decisions and we must support them with the best quality information we can obtain.

Do you think the tools described here may be useful towards making primary prevention choices truly personalized?

April 30th, 2014

Thinking About Risk

John E Brush, MD

The new ASCVD risk and lipid guidelines created quite a stir. People have questioned the accuracy of the risk calculator and the wisdom of giving statins to people above the 7.5% 10-year risk threshold. We have had a very robust and good discussion. But I have been wondering about how our patients will perceive their risk. Will they truly understand what we mean when we give them an estimate of their 10-year risk? It is conceptually easy to talk about an LDL target, but it is much harder to understand one’s 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event. The difficulty of wrapping one’s head around the concept of risk may be part of what is driving the controversy over the risk guidelines.

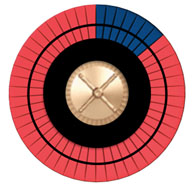

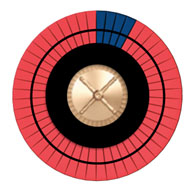

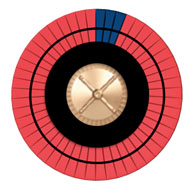

One way to visualize the idea of individual risk is to use an image of a roulette wheel. Imagine that each of us has one spin of our own roulette wheel and that spin will determine our 10-year cardiovascular outcome. We can change the design of our own roulette wheel to reflect our own 10-year cardiovascular risk.

Imagine a wheel with 50 spaces, some dark, representing bad outcomes, and the others red, representing good outcomes. Increasing the risk increases the number of dark spaces. If we stop smoking, we can reduce the number of dark spaces by roughly half. If we start a statin, we can reduce the number of dark spaces by about 20%.

Figure A shows the roulette wheel for a 59-year-old African-American man with a total cholesterol of 220, HDL of 40, with untreated systolic blood pressure of 120, without diabetes, who smokes. The 10-year ASCVD risk is around 13%. If he stops smoking, his risk drops to 8%, as shown in Figure B. With statin treatment, the risk drops further to about 6%, as shown in Figure C. The roulette wheels give a visual demonstration of the absolute and relative risks. If you had just one spin of the wheel, which wheel would you prefer to use? Are you willing to take a statin for 10 years to go from the wheel in Figure B to the one in Figure C?

Figure A Figure B Figure C

Risk is another word for probability, something that isn’t always easy for people to think about. Some consider it to be the observed frequency of an outcome, measured repeatedly over the long-run. Pictorial displays of little icons can visually show this notion of probability, but they don’t display what is really going on with the risk calculator. Others use a Bayesian or subjective notion, where probability is one’s degree of belief that a particular outcome will occur. A third example is to view probability from a design point of view. How we design a roulette wheel, a coin, a die, or a lottery can determine the frequency of events over the long-run, or our degree of belief about the outcome for a single individual. We can design our own roulette wheel through risk factor modification. As the saying goes, we can make our own luck.

The roulette wheel analogy may help us wrap our heads around the concept of individual risk and explain this concept to our patients. To read more about risk, I highly recommend a new book called Risk Savvy: How To Make Good Decisions by Gerd Gigerenzer.

How do you think about risk?

April 29th, 2014

Dietary Fiber After MI Linked to Improved Survival

Larry Husten, PHD

Consuming more dietary fiber after myocardial infarction is associated with a reduced risk for death.

In a report published in BMJ, researchers analyzed long-term data about diet and other risk factors from more than 4000 healthcare professionals who had an MI. Nine years after the MI, people who were in the highest quintile of fiber consumption had a 25% lower risk for death from any cause. Overall, there was a 15% reduction in mortality risk associated with every 10-g/day increase in fiber intake

The strongest association was observed for fiber derived from cereals and grains. A strong benefit was also found for people with the largest increases in fiber consumption after their MI.

The findings remained significant after adjustment for other factors known to influence survival after MI. However, the authors acknowledge that they were unable to “fully adjust for all known or unknown healthy lifestyle changes, and results may still be subject to modest residual and unmeasured confounding.”

The authors note that fewer than 5% of people in the U.S. consume the minimum recommended amount of fiber (25 g per day for women and 38 g per day for men).

April 28th, 2014

Selections from Richard Lehman’s Literature Review: April 28th

Richard Lehman, BM, BCh, MRCGP

CardioExchange is pleased to reprint this selection from Dr. Richard Lehman’s weekly journal review blog at BMJ.com. Selected summaries are relevant to our audience, but we encourage members to engage with the entire blog.

NEJM 24 Apr 2014 Vol 370

High vs. Low BP Target in Patients with Septic Shock (pg. 1583): The New England Journal has put so many good articles online first lately that I’ve left myself with thin pickings this week. This big French study of blood pressure targets in septic shock has been on the website for some weeks, and I didn’t comment on it sooner because I have only ever treated a single patient for septic shock in my working life. At the time I was a house officer on a urology ward. Despite my best efforts over a day and a night, he survived. Physiological emergencies cause a flow of adrenaline: there is an urge to do everything possible. A mean blood pressure of 65mm Hg doesn’t seem enough to keep anyone’s kidneys working, so this trial used adrenaline (epinephrine) or noradrenaline to push it up to a target of 80 or 85 in the intervention group. But these patients did no better than those whose BPs stayed at 65 or 70.

JAMA 23/30 Apr 2014 Vol 311

Effect of the Use of Ambulance-Based Thrombolysis on Time to Thrombolysis in Acute Ischemic Stroke (pg. 1622): Reading this week’s JAMA makes me think we need better outcomes research in stroke medicine. Two papers in this neurology-themed issue are devoted to systems changes aimed at reducing event-to-needle times for stroke; i.e. shortening the time between the actual event and the moment when tissue plasminogen activator reaches the cerebral circulation. One moment the leather-clad young RAF pilots are lounging in the sunshine drinking tea and smoking their pipes: the next moment the siren sounds and they are racing to their Spitfires to shoot down bandits. Never did so many owe so much to so few. But is this really true of crash teams for stroke? In this PHANTOM-S trial, ambulances in Berlin were set up with their own CT scanners, at a cost of a million euros each, and manned by teams trained to give tPA. Berliners giving a history suggesting Schlaganfall would rapidly hear the siren of an approaching Ambulanz; they would be whisked into the scanner; images would be relayed to waiting radiologists; and if there was clot, the tPA would go in before the vehicle reached the hospital door. This happened some weeks and not others. In the active weeks, alarm-to-treatment time was reduced by 25 minutes. Although the trial went on for 18 months and covered a catchment of 1.3 million people, it could not demonstrate any improvement in mortality. Never did so few owe so little to so many?

Door-to-Needle Times for Tissue Plasminogen Activator Administration and Clinical Outcomes in Acute Ischemic Stroke Before and After a Quality Improvement Initiative (pg. 1632): Meanwhile in the USA Gregg Fonarow and colleagues were trying out a new in-hospital protocol for reducing door-to-needle time in ischaemic stroke. All Get With The Guidelines (GWTG)—Stroke hospitals were encouraged to participate and each hospital received a detailed tool kit, including the 10 key strategies, protocols, stroke screening tools, order sets, algorithms, time trackers, patient education materials, and other tools. This massive effort across more than a thousand hospitals resulted in a reduction of median door-to-needle time from 77 to 67 minutes, and was associated with a before-and-after reduction in all-cause in-hospital mortality from 9.93% to 8.25%, and a rise of 5% in the number of patients discharged to their own homes. Note that we cannot know how much of this was due to any part of this complex intervention.

JAMA Intern Med April 2014 Vol 174

Different Time Trends of Caloric and Fat Intake Between Statin Users and Nonusers Among U.S. Adults (OL): Since taking a statin, I have got fatter. I am part of a trend, according to an analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999 through 2010 (N.B. I’m keeping the American “through” here because it is a useful construction). “Caloric and fat intake have increased among statin users over time, which was not true for nonusers. The increase in BMI was faster for statin users than for nonusers.” So far, so incontestable: this was a thoroughly conducted survey. But now for the speculation: “Efforts aimed at dietary control among statin users may be becoming less intensive. The importance of dietary composition may need to be reemphasized for statin users.” We’ve no idea whether this is actually true of this population, let alone individuals within it. It certainly isn’t true for me. I’ve always just eaten what I enjoy: I just need more exercise.

April 28th, 2014

Calorie, Fat Consumption Up Among Statin Users

Nicholas Downing, MD

Calorie and fat consumption increased significantly from 1999 to 2010 among statin users — but not among nonusers — according to a JAMA Internal Medicine study. The researchers conclude that “the importance of dietary composition may need to be reemphasized for statin users.”

The researchers evaluated 24-hour dietary recall data from nearly 28,000 adults participating in U.S. nutrition surveys over the 12-year period. They found that among statin users, caloric intake was 10% greater, and fat intake 14% greater, in 2009-2010 than in 1999-2000. No significant increases were observed among nonusers. In addition, statin users had a greater increase in BMI than nonusers did (1.3 vs. 0.4 units).

The authors speculate that statin use “may have undermined the perceived need to follow dietary recommendations.” They add that the aim of statin therapy “should be to allow patients to decrease risks that cannot be decreased without medication, not to empower them to put butter on their steaks.”