January 30th, 2019

I’m Sad That Interns Don’t Want to Do a Palliative Care Rotation

Justin Davis, MBBS

It’s an exciting time for final-year medical students in Australia. Exams are over. They’re in their last-ever clinical rotations, and they’ve finally found out in which hospital they’ll be starting their careers. Most are happy. Perhaps some aren’t, I dunno. But most are simply excited to finally start their intern year as doctors, having spent 8 or more years in college and medical school. Finally getting to practice medicine. I suspect the fact they’ll be getting a regular wage is also something they’re looking forward to. I was surprised when, all of a sudden, I could afford a bigger tv after a few weeks of work as an intern.

The final day of my own medical school time. Cricket on the right, Mario Kart on the left. And beer, of course.

Of course, finding out which hospital you’ll be working at also comes with finding out about rotations. These are definitely more varied than hospital choices — your new hospital will often offer a gajillion different rotations. (I wonder how many zeros a gajillion is? *looks it up* — Oh, it’s an unspecified large number. OK, so a gajillion is correct.) Here in the Land Down Under, our interns are required to have an emergency medicine rotation, a surgery rotation, and a general medical rotation in order to satisfy their intern training requirements, so those are not optional. The others could be anything. Perhaps even rotations you wouldn’t necessarily choose.

So, I was chatting with intern friends about their rotations. Overall they were pretty happy with their particular list of rotations for next year, but several people noted that their colleagues who were assigned palliative care rotations were trying to swap them out. And they wondered why anyone would agree to swap anything for a palliative care rotation.

This really saddened me. It made me muse and reflect on my own experiences as a palliative care intern and how good that rotation had been for my medical learning and growth. Why wouldn’t our newly minted doctors want to experience the personal improvement that working in palliative care could provide?

Of course, there is a story behind all of this (like most of the blog posts I write, I’ve come to realize). I was quite happy with my own intern rotations: with the aforementioned emergency, surgery, and general medicine already allocated, I was given palliative care and orthopaedic rehabilitation as my optional ones. My own intern year started in emergency medicine.

The next paragraph is tricky. Emergency medicine was a… difficult rotation. Outside of intensive care, which I would experience later as a registrar (have you ever felt the dread of standing alone at 2am staring at an ECMO machine while your patient has just crashed, having never seen an ECMO before or had anything to do with one and wondering what the next steps are? I have.), emergency medicine was, by far, the most challenging experience I have had as a doctor. I think everyone, when they start out, has an existential crisis when they realize they have the responsibility of, you know, caring for sick patients. But, if you start in general medicine, you have ward-based registrars to run decisions through, which lessens the brunt of that responsibility.

Palliative care is about endings, but endings can be beautiful. I love sunsets, so putting nice ones into this blog goes with the spirit of palliative care.

There is a different culture to emergency medicine. Cold neon lights illuminate that place, no matter what the time or weather is outside. Like all of medicine, it’s a grinding wheel that never stops, but the relentless pressure there is something else. I remember walking down the corridor one day, with monitored cubicles to my right that continually beep and alarm like every patient is going into VT (they aren’t) and my second-favourite staff base to my left (you can have favourite staff bases. Don’t look at me like that), and thinking I had just wasted the last 8 years of my life. I should have stayed working at Dan Murphy’s (Uncky Dans is a liquor store chain in Australia, and I have to admit, if you’re going to have a part-time job to support yourself through university, you couldn’t ask for a better one). And all that excitement about working? Starting out? Finally being a doctor? Gone. Extinguished under the cold neon lights, while another category 2 comes into resus 3, and the monitored cubicles alarm for no good reason.

But, something happened that changed my perspective. That “something” was my palliative care rotation, my second rotation after the battering and brutal introduction that emergency medicine gave me. Instead of having to move patients to somewhere, anywhere, as long as it’s out of emergency, quick! Quick! And the relentless pressure … palliative care was a completely different experience. We had time for patients and their families. To sit down and talk with them about the issues they were having and what we could do to make their lives better. We didn’t need to investigate everything to make sure it wasn’t dangerously lethal, or to do things quick! Quick! Instead, the focus was on comfort, dignity, and making people’s lives better in what time they had left. Focusing on their needs and how we could best address them. Time. Empathy. Compassion.

It changed my outlook on wanting to work as a doctor and my enjoyment of the job. It was a liberating experience to be a part of a team of doctors and nurse practitioners (whom I cannot thank enough) who simply made people’s lives better without investigating, referring, testing, or moving patients. Just talking, focusing on essential medications that would take their symptoms away, and having the time to spend with patients and their families, listening to their concerns. You could tell it was a valuable experience for the people whom we consulted on, and it certainly was for me as well.

And another sunset, taken one night on the three and a half hour drive to my rural hospital placement.

The business that is specialist medicine has the potential to draw out the worst qualities of the medical grindstone. Sometimes, we simply have too much to do in one day. This is why I was saddened to learn that others wouldn’t want to experience a rotation like palliative care during their own intern years. Perhaps they won’t come to it from as low place as I did, but the experiences and the satisfaction of just making people feel better is something that new doctors shouldn’t miss out on. When I fnd myself having difficult discussions with patients and their families, I often reflect on the conversation skills that palliative care taught me. But mostly, it was nice to do so much for people by doing so little. A palliative care rotation is definitely worth swapping into.

“With time, every epilogue extends into a sequel.”

January 5th, 2019

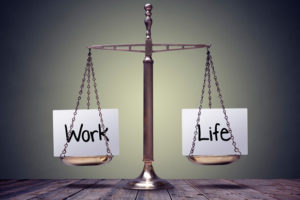

I Call BS on Work–Life Balance

Ellen Poulose-Redger, MD

Physician wellbeing, burnout, and “work-life balance” are pretty common topics in training. We start at intern orientation, discussing how to work 80 hours a week, eat, sleep, exercise, and still have some semblance of a social life. It’s like we’ve forgotten the origins of our job title: “resident” or “house staff” — implying that, until recently (and even now, in places outside of North America), we, the physicians-in-training, lived at the hospital. And that sometimes (often times), we still spend more time at the hospital or clinic than we do anywhere else in a week. There are 168 hours in a week, and just under half of them are considered reasonable for us to work. That’s double a “normal” full-time job (40 hours/week).

I’m definitely not saying that medical training, should be shorter or encompass fewer hours. If anything, sometimes it feels like it should be longer (or maybe that’s just the slight fear of my first “attending” shifts coming up — because now it really is my call on things). We have huge responsibilities, and that responsibility requires intensive training. In all honesty, another key component of medical training is the lesson that we are all life-long learners — that our education cannot and does not stop simply because we graduate, get an attending job, and go into practice. There it is again — a word that, if we look at it, reveals the origins of medicine. We practice. We try things, we learn new things, we keep working at getting better. This is not to say that the first patients I see on my own will be poorly taken care of, but just that (as with many professions) we all get better at our jobs over time. We hone that sixth sense, trust our guts a little more, get better at pattern recognition, and know when to call other experts to help us and our patients. We keep practicing, trying to make perfect.

That search for perfection is inherent to many physicians. As a group, we are type A, driven, competitive people. It is one of the things that allows us to give nearly a decade of our lives to school and training to do our jobs — prime years, usually in our 20s and 30s. Those same years, though, are the ones when other people are starting careers, developing hobbies and interests, buying first homes, and starting a family. When we do go looking for our first jobs (as residents, fellows, and first-time attendings), we are expected to be ambitious, well-rounded, compassionate, and well-developed people, not automatons. So, during our medical training, we have to fit a life into the 88 hours per week when we are not at work.

This brings me back to the idea of balance. I take issue with the phrase “work–life balance.” When I picture a balance, I picture something where the two sides offset each other, like old-fashioned scales. With this picture in mind, then, work–life balance would mean that the two sides are equal. In my 88 hours of “personal” time each week during residency, I drive to and from work (round trip totaling at least 1 hour each day), sleep (hopefully at least 7 hours each day), shower/get ready for the day (and, since I’m a girl, that realistically takes an hour each day), and cook/eat/do laundry/clean my apartment/see my husband. That doesn’t really leave a lot of time for any sort of a life, hobbies, research, or anything else that would help me to be a thriving and well-rounded person. Something always gives when people are busy (regardless of their field), and it is usually their personal lives.

a balance, I picture something where the two sides offset each other, like old-fashioned scales. With this picture in mind, then, work–life balance would mean that the two sides are equal. In my 88 hours of “personal” time each week during residency, I drive to and from work (round trip totaling at least 1 hour each day), sleep (hopefully at least 7 hours each day), shower/get ready for the day (and, since I’m a girl, that realistically takes an hour each day), and cook/eat/do laundry/clean my apartment/see my husband. That doesn’t really leave a lot of time for any sort of a life, hobbies, research, or anything else that would help me to be a thriving and well-rounded person. Something always gives when people are busy (regardless of their field), and it is usually their personal lives.

I don’t necessarily have a way to fix this: We need long and intensive medical training to be good at our jobs. We need to find time to sleep and take care of ourselves so that we can first do no harm (to ourselves). I just don’t think it is fair to say we are striving for balance, because we aren’t. We are striving for survival, until the next step in our careers, when we might get more time for ourselves. We are putting off relationships, families, houses, retirement funds, and many other things while we train. Maybe one way to help with this is to develop robust programs at every institution to help trainees (and honestly, all physicians) accomplish some of these life tasks (e.g., laundry, food, cleaning services). But I think one (free) thing that would to help with this is to just stop calling it “work–life balance” and admit that it will always be unequal and weighted toward work while we are in training, and perhaps for a large part of our careers. One of my husband’s attendings once told him that you can have two out of three: family, fame, or fortune — but not all three. Something will always give in medicine. It’s just easier to accept that we’re giving up something if we don’t pretend we can have it all.

December 26th, 2018

Trapped – Chronic Pain and Opioids

Ashley McMullen, MD

“I feel like a caged animal” — My patient offered me this lens through which to view his life seeped in chronic pain. For him, pain dictated his entire sense of being — it was something that simply could not be distilled down to a single value on a 10-point scale. The cage represented the restriction of life and the boundaries within which he was allowed to experience, let alone enjoy, even the most mundane of activities. It also represented a loss of control. Long before our paths crossed, this patient had access to high doses of prescription medications that danced with the mu-receptors in his brain and dulled his senses. From the time he woke up in the morning, to the time he went to bed at night, these pills offered transient entry into a perceived life of freedom.

However, somewhere in the intervening years, the line between freedom and captivity became blurred. Questions of safety were raised as doctors struggled to define whether this patient was controlling his pain, or was being controlled by his pain medications. He was ultimately diagnosed as having an opioid use disorder. Thus began a long tapering plan that slowly drained this man of what little semblance of sovereignty he had in his life. He felt he was being backed further and further into this “cage,” whose walls were now personified as his doctors, who were locking him in and throwing out the key. This is the situation under which I first met this patient in clinic. —

However, somewhere in the intervening years, the line between freedom and captivity became blurred. Questions of safety were raised as doctors struggled to define whether this patient was controlling his pain, or was being controlled by his pain medications. He was ultimately diagnosed as having an opioid use disorder. Thus began a long tapering plan that slowly drained this man of what little semblance of sovereignty he had in his life. He felt he was being backed further and further into this “cage,” whose walls were now personified as his doctors, who were locking him in and throwing out the key. This is the situation under which I first met this patient in clinic. —

When it comes to treating chronic, noncancer-related pain in the context of a burgeoning opioid epidemic, I feel weak and disempowered. It is my personal primary care Kryptonite. Although we have many great multi-modal treatment options, it can be incredibly challenging to impanel patients who, at one time or another, received chronic prescription opioids. Currently, no fancy blood test, imaging, or invasive procedure exists that can objectively measure the physical and emotional burden of pain. Patients therefore are beholden to the subjective disposition of doctors who must decide how to treat pain, and in whom. So, when disagreements arise with patients on this topic, as they often do, it can mean the difference between a good day in clinic and a hellacious one.

Today’s trainees are grappling with a crisis that is in large part attributable to yesterday’s standard of practice. It is one of the many toilsome aspects of general medicine that pushes trainees to choose specialty over primary care. In April of this year, I was fortunate to attend C.R.I.T., a conference on addiction medicine run by top leaders in this field from Boston University. The conference is designed for chief residents, fellows, and faculty mentors to gain immersive training in managing substance use disorders. The experience also involved learning best practices for supporting residents in taking care of these patients who, while challenging, incur a substantial amount of stigma from healthcare providers.

Today’s trainees are grappling with a crisis that is in large part attributable to yesterday’s standard of practice. It is one of the many toilsome aspects of general medicine that pushes trainees to choose specialty over primary care. In April of this year, I was fortunate to attend C.R.I.T., a conference on addiction medicine run by top leaders in this field from Boston University. The conference is designed for chief residents, fellows, and faculty mentors to gain immersive training in managing substance use disorders. The experience also involved learning best practices for supporting residents in taking care of these patients who, while challenging, incur a substantial amount of stigma from healthcare providers.

One poignant take-away from this conference came from the keynote speaker, Michael Botticelli, a former director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy who also struggled with addiction. To paraphrase his comments, he stated that, as doctors, we no longer have the luxury of choosing whether or not to deal with pain and/or addiction. This epidemic affects all of us and, as such, we all have a responsibility to get informed and to treat patients as safely and empathically as possible.

In the short time we’ve known each other, my patient has already managed to run me through the gauntlet of emotions. He’ll offer me glimpses into the depth of his suffering then immediately blame everyone from distant relatives to Barack Obama. Although I have learned to set strict boundaries with patients on my tolerance for diminutive language, I recognize how opioid use disorders can destroy even the most beloved of personalities. It might just take a stronger effort on the part of physicians to see the human beings stuck behind the thick veil of this particular disease. My hope is that, with time and trust, my patient and I can work together to find a way out.

In the short time we’ve known each other, my patient has already managed to run me through the gauntlet of emotions. He’ll offer me glimpses into the depth of his suffering then immediately blame everyone from distant relatives to Barack Obama. Although I have learned to set strict boundaries with patients on my tolerance for diminutive language, I recognize how opioid use disorders can destroy even the most beloved of personalities. It might just take a stronger effort on the part of physicians to see the human beings stuck behind the thick veil of this particular disease. My hope is that, with time and trust, my patient and I can work together to find a way out.

December 20th, 2018

Medicine Robbed Me of My 20s

Scott Hippe, MD

“Medicine robbed me of my 20s.” I’ve heard the line many times in my medical training. It often comes accompanied by a long sigh, a slow sip of coffee, and a glazed stare off into the distance. “Imagine what could’ve been,” the seasoned physician muses, “if I had my 20s to do over, without medicine.”

But now, I am mere months away from leaving my 20s behind. To be completely honest, I often feel similar to those physicians I heard earlier. I see my friends outside medicine doing exciting things and visiting exciting places. And then there is my brother, a teacher, who is off work for summers and every single family holiday. Sometimes — especially on 28-hour shifts — I wonder if medicine is really worth it. I wonder if the journey is leading me to my best self.

Lamenting the things I’ve missed

We have a maladaptive tendency as humans to focus on that which is not, rather than appreciating the good in what actually is; we define ourselves by what we miss, rather than by what we catch. In this vein, I started making a list of things I missed in my 20s. Then I got depressed. But here is what I had, to start:

- Missed lunch today and many days; man, am I grumpy today

- Missed going out last Friday

- Missed my alarm and a call to deliver one of my pregnant patients

- Missed calling my mum on her birthday

- Yikes, missed zipping up my fly before ICU rounds

- Missed pickup basketball on Saturday, and the Saturday before that

- Missed registering for the CME conference all my friends attended

- Missed being home for the holidays

- Missed diagnoses, including DKA, stroke, and heart failure

- Missed family weddings, reunions, and a tragedy

- Missed the chance to travel abroad with friends

What misses mean for resident wellness

Focusing on misses like this has a negative effect, not just on big-picture life satisfaction, but also on day-to-day wellness. The bitterest pill to swallow in residency for me is not the long hours. The most soul-crushing piece is being drawn away from places you want to be and people who are dear.

There is dissonance here: I desire to be well in my life and work, but medical training is challenging and exceedingly time-consuming. The realities of residency take me away from the things that make me “well.”

Residencies are waking up to the idea of wellness. At my residency, we have been trying to increase dedicated administrative time to decrease charting outside of clinic. Our wellness committee puts on quarterly events to build community. We have a supportive faculty.

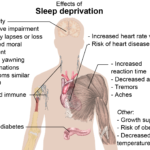

Having adequate time to sleep, exercise, and experience a loving community forms the perfect foundation. Yet without feeling good about the work, efforts to improve life outside of residency responsibilities ultimately fall short at achieving whole-person wellness. We just work too stinking much for this not to be the case.

Encountering a low point

Long hours and some uncertainty about my future after residency caught up to me recently. While transient, this bump in the road put me in an anxious and sleep-deprived condition. My work felt devoid of meaning. Fifteen-plus hour workdays are long ones if you feel empty.Without prompting, the wife of one of my middle-aged male patients said “Dr. Hippe, you’re the first doctor my husband has been able to tolerate in 50 years.” That hint of positive connection made me start paying attention again. The next day, two infants I’d delivered in previous months came in for checkups. They were thriving, their families were happy, and I shared in their joy of new life. Unknowingly and in subtle ways, my patients helped me find my center at work again.

Finding wellness at work

An alumnus from my residency recently sent a message about wellness. She quoted an article published in JAMA, in which the author relates “I can think of no other dichotomy so damaging to a young physician or the patients he or she will treat, than to imagine that life begins only once a shift has ended” ( This former resident then added her own thoughts: “How can we re-frame and experience work as an enjoyable part of life rather than something entirely separate from who we are and how we live?”

What I appreciate most about the question is that there is no singular best answer. Personally, I often find wellness at work through connecting with my patients. Other times it has been support from my resident community, or the exhilaration of becoming competent at a new procedure. The answer to the question will be different for everybody, and can change along the way.

I am sure of one thing, though: the answer to what makes us well at work is worth pursuing, both individually and as groups of residents and physicians.

December 11th, 2018

No, I Am Not Patient Transport

Cassandra Fritz, MD

“Oh, you’re here to take me to my test.” I have heard this too many times to count, and I have come to perfect my response. “No, I am not patient transport, your social worker, or your nurse. I am your doctor.” After a moment of confusion, I usually see a facial expression signaling that the patient is reframing his or her initial thoughts. Maybe I am misidentified because I am young, or black, or female. No matter the reason, I get annoyed instantly every time this happens. Do patients have some preconceived notion about who I am? I always conclude my internal dialogue wondering… Will they trust me?

In sharing these experiences, I feel that women, especially minority women, deal with this more than other physicians. Although this issue may seem insignificant to some, continually having to define your role drains morale and can erode confidence. In spite of my white coat and MD, patients mistake me for everything BUT a doctor. I have joked that, even if I tattooed MD on my forehead, there would still be misperceptions about my position. All kidding aside, the repeated misunderstanding about women being physicians speaks to the strength of implicit bias in medicine.

In sharing these experiences, I feel that women, especially minority women, deal with this more than other physicians. Although this issue may seem insignificant to some, continually having to define your role drains morale and can erode confidence. In spite of my white coat and MD, patients mistake me for everything BUT a doctor. I have joked that, even if I tattooed MD on my forehead, there would still be misperceptions about my position. All kidding aside, the repeated misunderstanding about women being physicians speaks to the strength of implicit bias in medicine.

Implicit bias stems from our past experiences and stereotypes. It is an unconscious process that allows our brains to make automatic associations based on initial yet superficial qualities. Basically, implicit bias is one way our brain sifts through the information constantly bombarding us. Patients may be more at-risk of relying on automatic unconscious associations when they are stressed or sick. Yet, I have often wondered, do these interactions affect patient care?

So if you find yourself annoyed by repeatedly stating “I am your doctor,” here are a few things to consider:

Implicit Bias Is Strong

Physicians’ implicit bias toward patients is commonly discussed. Yet we aren’t taught how to deal with being on the receiving end of bias. Nonetheless, the “hidden curriculum” during medical school and residency has provided models of how to navigate these situations. What I have found most helpful is to quickly establish common humanity with patients. By sharing small aspects of my story, I can help people disassociate from their previous bias. Giving patients the opportunity to reconstruct their thoughts about who I am, and hopefully establish a trusting and a therapeutic relationship.

Physicians’ implicit bias toward patients is commonly discussed. Yet we aren’t taught how to deal with being on the receiving end of bias. Nonetheless, the “hidden curriculum” during medical school and residency has provided models of how to navigate these situations. What I have found most helpful is to quickly establish common humanity with patients. By sharing small aspects of my story, I can help people disassociate from their previous bias. Giving patients the opportunity to reconstruct their thoughts about who I am, and hopefully establish a trusting and a therapeutic relationship.

Confronting Bias Is Important

I would be debt free if I had $10 every time a nurse asked for orders from my 6 ft+, usually white, male medical students in their short white coats. We all have biases about the type of person we look to for help.

I would be debt free if I had $10 every time a nurse asked for orders from my 6 ft+, usually white, male medical students in their short white coats. We all have biases about the type of person we look to for help.

During my second year of residency, I worked with an amazing female fellow in the ICU who helped me find my voice in high-stakes situations. She encouraged me to correct people when they were looking to the wrong members of the team for orders or guidance. She taught me something important in that moment — you have to confront bias head on.

Acknowledgement Is Key

As I mentioned above, confronting bias provides an opportunity for people to reconstruct their initial associations. This confrontation can be tricky though when a patient is involved. What is the appropriate way to “check” your patient? I think most of us already do this in a proper manner: We politely correct patients (no matter how many times it takes). Is it hard to repeatedly define your role? Absolutely! Yet this is why I think acknowledgement of the bias against you as a physician is very important.

Physicians need to acknowledge to their team that they are being bombarded by waves of implicit bias. Because I just can’t believe that this doesn’t affect us. When this happens to me, I conscientiously tell my team about the interaction. I do this not to make people feel uncomfortable, but to make sure I am scrutinizing my own bias so as not to affect patient care.

Implicit Bias Is Everywhere

We are all guilty of making quick associations, especially in high-stakes situations. It is important to make patients feel comfortable, but there isn’t anything wrong with clarifying and re-clarifying your role. Most importantly, we should all try our best to support each other during these situations. Be open to the fact that some colleagues might need to air their frustrations as a way to manage their own bias toward patients. Acknowledging our human flaws and supporting each other really is what’s best for us and for our patients.

December 4th, 2018

Conferences Are Really About Mental Health Breaks

Justin Davis, MBBS

I recently attended the Australian and New Zealand Society of Nephrology’s (ANZSN) annual conference. I had a really good time. I had been to one of these before, when it was in Perth a few years ago, but that was way before I was accepted into the nephrology program. I remember the weekend being a whirlwind of getting out and back to Perth on a Friday and Sunday, attending as many of the talks as I could, and also missing a live event for one of my favourite video games that only ran that weekend (go figure). While that first conference was an enjoyable experience, the one I went to recently in Sydney was so much more enjoyable, and, naturally, when I notice something like that, I get to musing as to why that’s the case.

Darling Harbour on one beautiful morning. Only made better by the addition of coffee (not pictured).

I had been looking forward to this conference for a while. Before I went, I was excited both about attending a conference hosted by the society to which I had just been accepted into training and about the scientific talks and learning that would happen there. But, as the week went on, I started realising that it wasn’t just the lectures that I was appreciating. Instead, as my blog title suggests, it was more the time off, the break from the grind that is clinical work — a few days where I didn’t have to battle the phone or the clinic, or try to solve the multitude of issues that crop up on a daily basis. Instead, my biggest worry on any conference day was where was I going to source my morning coffee from so that I could be awake enough to pay attention to the aforementioned talks. (I am not a morning person, and this is especially true before I have had some sort of warm caffeinated beverage. I can’t start my ward round without one. Also, if anyone is curious, my hotel had a café in the lobby that did pretty good coffee, so this issue was solved very quickly).

Appreciating the poster viewing part of the conference, mostly by pointing out our co-regs specific posters for our amusement.

But it’s more than just the simple time off from work that made the conference enjoyable. If that were the case, I would be writing about every weekend that I have off.(Curiously enough, I’m writing this blog post on a Sunday evening where I have had a lovely little weekend off. It’s sunny and warm for the first time in ages here in the Land Down Under [well, the Victorian portion of it. I mean, Queensland is always sunny. Like Philadelphia]). I mentioned above that I was looking forward to my first nephrology conference as a nephrology registrar, and that’s because, in a speciality program, there’s something nice about being part of a group of varied, but still sorta-like-minded, people (after all, there was something that all drew us all to the kidneys). Where I work, I’m the only renal advanced trainee, which is nice, as I have formed close relationships with the staff around the unit (after all, I am the conduit for most things going through that unit). But this year, I’ve also been privileged to meet and become friends with a lot of the other nephrology trainees in my state, through various events and phone calls between hospitals. But I don’t have much to do with my registrar colleagues on a day to day basis, so I was appreciative of this year’s conference for the social aspect of it and for getting to spend some time with everybody else. Aside from Friday night travel, which was a scrambled mess of trying to get to the airport on time, every night at the conference was spent out for drinks, good food, and generally gallivanting about Sydney. (Have you ever noticed that if you’re trying to leave the hospital early or, at the very least, on time for something, instead of having a nice quiet day the hospital is insanely busy every time? I swear Murphy’s law and medicine have some sort of pact.) Admittedly, even on the Friday evening, I ran into some of the other registrars at the airport and had a nice chat (as well as the rather amusing group chat situation about the storms in Sydney that were cancelling various flights and the social media messages that created). And this, to me, was the key reason why I enjoyed this conference so much more than the last one; even though they both had scientific talks, it was the social aspect of this one that made it much more enjoyable. (Curiously enough, I also missed out on the first weekend of a launch of the newest edition of the same video game that I missed out on in Perth a few years ago. Go figure again, hey?)

Conferences aren’t just about the talks, the time off, or the social aspects. There’s also the opportunity to explore new places. I’ve actually been to Sydney a few times (including a rather amusing time where we stayed in what I swear must have been the hottest, most cramped, and non-air-conditioned backpackers’ hostel in the world during the middle of summer. It was great!), but this was the longest time I’ve spent there. Sydney has a heap of cool things to see in it, and Darling Harbour (on which our conference was held) is always a very pretty and pleasant place to visit. It was nice to get out and explore some more of the city, including going for a run pretty much every day I was there — including the opportunity to run around Circular Quay and enjoy the Harbour Bridge and the Opera House. (It’s fun to be a tourist even in your own country sometimes). Even getting the time to sit out on Darling Harbour with a beer and a book (my favourite author managed to release his newest book right in the middle of the conference, which was excellent timing — I actually devoured it in a couple of days) watching the sunset was a refreshing experience, one I don’t have the opportunity to do during everyday life.

Of course there is a selfie in front of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. I mean why wouldn’t you take that opportunity whilst you’re there?

It’s important to note that I did also enjoy the talks that were given during the conference, especially the one emphasising updates in granulomatous with polyangiitis (GPA) with a discussion on the recent PEXIVAS trial. I feel like this one is going to create controversy in the nephrology world for a while yet. It probably was the highlight for me. But the conference was so much more than that. It was time off work, socialising, the chance to explore a new city, and even just little things like going for a run around Darling Harbour listening to music (from the same video game I was missing out on. Don’t look at me like that …) or sitting with a book and wine, watching the sunset. That was the conference. And that’s what made me come to the realisation that conferences are more about the mental health break than anything else. And hey, if you get to experience that every year or so then it makes conferences more than worth it.

“The greatest Warlocks understand how little they understand.”

What’s that? More random quotes? Sure, why not?

November 6th, 2018

Making the Most of the Holidays as a Resident

Ellen Poulose-Redger, MD

It’s that time of the year again — Halloween has passed (and with it, the best excuse for an adult to dress up in costume), and the winter holidays are just around the corner. I was in a store on November 1st, and Christmas decorations were being put up. Already. Whether or not you happen to celebrate a particular holiday, this time of the year is associated with friends and family and togetherness. For many residents, though, it might be the first time that they spend many (if not all) of the holidays away from family and friends they grew up with. We all make new friends (and some would say, family) in residency and beyond, but there is also something about being home for the holidays.

As a kid, I lived within 45 minutes of all four of my grandparents and was lucky enough to have them all around until 2010. Many Thanksgivings were spent at my dad’s parents’ house, where aunts and uncles and family friends and really, anyone, came to have an American Thanksgiving and then a second round of Indian food. It was a tradition that started in the 1970s when my grandparents, immigrants to the U.S., wanted their children to grow up with a true “American” Thanksgiving — turkey and trimmings, pies, and enough food for four times as many people as were actually in attendance. Christmas for us was not as stereotypical. Both of my parents are physicians, so Christmas happened sometime around the 25th of December, whenever they could both be off and awake at the same time, and the focus was not on gifts (although we did receive them). The focus for Christmas was being together.

As a kid, I lived within 45 minutes of all four of my grandparents and was lucky enough to have them all around until 2010. Many Thanksgivings were spent at my dad’s parents’ house, where aunts and uncles and family friends and really, anyone, came to have an American Thanksgiving and then a second round of Indian food. It was a tradition that started in the 1970s when my grandparents, immigrants to the U.S., wanted their children to grow up with a true “American” Thanksgiving — turkey and trimmings, pies, and enough food for four times as many people as were actually in attendance. Christmas for us was not as stereotypical. Both of my parents are physicians, so Christmas happened sometime around the 25th of December, whenever they could both be off and awake at the same time, and the focus was not on gifts (although we did receive them). The focus for Christmas was being together.

Holiday celebrations during residency

Fast forward to residency, when my husband and I moved literally halfway across the country (Kansas to New York). Our first year in NY, I worked Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve, New Year’s Eve, and New Year’s Day — somehow, I managed to have actual Christmas Day off. [I’m sure he worked at least one of those, too, but while the urology service slims down for the holidays, the various medical services I’ve been on over the years do not.] My  second and third years weren’t quite as bad, but in a two-physician household, you can bet that on most holidays, at least one of us is working. That’s how it goes — patients will always be sick and in the hospital — it’s part of being a physician.

second and third years weren’t quite as bad, but in a two-physician household, you can bet that on most holidays, at least one of us is working. That’s how it goes — patients will always be sick and in the hospital — it’s part of being a physician.

Being away from our families during the holidays isn’t fun or easy, but my husband and I have learned to make it work. We participate in Friendsgiving (coincidentally the afternoon/evening after the urology in-service exam), our co-residents have organized “Secret Santa” gift exchanges, and we try to have a Christmas meal with members of our work family. We’ve even experienced our first Hanukkah, where I made very non-kosher lasagna.

“Holidays for the strays”

About 10 years ago, my parents started hosting “holidays for the strays.” This was an open invitation to their colleagues and residents to come over on Thanksgiving or Christmas or some random day near to the holidays to share a meal and spend time together. Over the years, this has morphed from a last minute “oh, no, these residents are going to be all alone on Christmas” to a fully planned, official headcount, catering-to-various-dietary-restrictions event that everyone looks forward to each year. [In fact, one of the Jewish attendings had his first Christmas dinner last year!]

About 10 years ago, my parents started hosting “holidays for the strays.” This was an open invitation to their colleagues and residents to come over on Thanksgiving or Christmas or some random day near to the holidays to share a meal and spend time together. Over the years, this has morphed from a last minute “oh, no, these residents are going to be all alone on Christmas” to a fully planned, official headcount, catering-to-various-dietary-restrictions event that everyone looks forward to each year. [In fact, one of the Jewish attendings had his first Christmas dinner last year!]

When the “stray holidays” first started, my siblings and I understood that it was about bringing people together, but now, as a (chief) resident, I see how it is so much more than that. Holidays for the strays is a way to make sure that residents and faculty know they belong to a bigger family than the one they grew up with — they belong to the family of medical professionals where someone must work 24/7/365 to take care of others. Holidays for the strays are a way to make sure no one is sitting at home with leftovers or takeout on a day when everyone else is crowded around a table with family and friends. It is a way to get to know your colleagues outside of the hierarchy of the hospital or clinic. And most importantly, it is a way to ensure that even for those of us who work most (if not all) holidays, there’s still a table full of family and friends waiting to squeeze you in.

This year, as I made one of the residency class schedules, I notated where various holidays fell (including major Jewish and Muslim holidays) and tried to give the appropriate people days off on the appropriate holidays when it was possible. It was my way to try to ensure that the residents had a chance to pull a chair up to a table and spend time with those they love.

This year, as I made one of the residency class schedules, I notated where various holidays fell (including major Jewish and Muslim holidays) and tried to give the appropriate people days off on the appropriate holidays when it was possible. It was my way to try to ensure that the residents had a chance to pull a chair up to a table and spend time with those they love.

Maybe I can’t have you all over for my Christmas tenderloin, or bake up a bunch of pies for everyone for Thanksgiving, or share my famous French toast with you for New Year’s brunch, but I can encourage everyone to do something together, even for a few hours on just one of the holidays. You can bet that once we finally move on from living in apartments, we’ll be having our own “holidays for the strays.” And, for any of my residents reading this, I’ll see you on Thanksgiving — at the hospital.

October 25th, 2018

Part of the Equation, but Not Equal

Ashley McMullen, MD

Fall is finally here — the weather is changing, good TV shows are back on, and, for residency programs, interview season is fast approaching. That means it is time, once again, to choose the next class of interns to take the formative next step in their careers. In this process of selecting a few from many qualified applicants, the concept of diversity is one that comes up often. Its value is especially relevant in medicine as we seek to build a workforce of providers that is, at least partially, representative of an increasingly diverse patient population. However, while we recruit more trainees who are underrepresented in medicine (URM), it begs the question – “What are residency programs doing to both assess and address the environments in which their URM physicians practice?”

The results of a survey that went out to residents at my own institution found that, among the demeaning interactions encountered either directly or indirectly in the workplace, the vast majority originated from patients or their families. It comes as no surprise that the intense divisions playing out across our TV screens and social media do not cease to exist inside the hospital walls. Indeed, several recent mainstream and peer-reviewed publications have documented instances of overt discrimination leveled at physicians. Likewise, in a 2016 New England Journal of Medicine perspective, Paul-Emile et al. cite a particularly egregious incident that took place at one of our hospitals (N Engl J Med 2016; 374:708). Here, they outline an approach to dealing with racist patients. However, more often, the subtle instances of perceived bias present the biggest challenges.

One evening on a particularly arduous shift in the emergency department, I was readying myself to deliver bad news to a patient’s family. The medical student rotating with us that night asked me if he could come observe the conversation as a learning opportunity; I replied, “of course.” To be sure, delivering bad news is never easy, but I felt I’d had enough experience at that point in my training to confidently model this skill. Upon entering the waiting area, several of the patient’s family members were sitting patiently with silent apprehension. Anticipating the challenging news to come, they wanted to wait for one more relative to arrive before starting the conversation. When this person walked into the room, she moved with authority and purpose — clearly, she was the spokesperson for the family. I stood up to greet her, and although we made eye contact, she continued moving right past me and up to my tall, white, youthful-appearing, male medical student. “You must be the doctor,” she said.

This story is not unique among those who are underrepresented in medicine, but I can tell you how it uniquely affected me. In that moment, when I needed to evoke empathy and compassion for this family, I found myself trying to sit taller and to speak louder and with more confidence. I was trying to increase my psychological size as way of compensating for the fact that I couldn’t be the doctor this family expected or wanted at this difficult time. I often find myself going to meet a new patient and wondering how they will react when they see me — will they be pleasantly surprised, disappointed, angry, or indifferent? Regardless, I know that whether the patient is wearing a red MAGA hat or a red Colin Kaepernick jersey I must afford them the same level of care and professionalism. It is yet another example of how the rigors of medical training are compounded by the realities of our current sociopolitical climate.

As long as physician burnout continues to be on the forefront of conversation, we must also address the additive impact that these types experiences have on URM trainees and attendings. Many institutions do well to incorporate talks on implicit bias, diversity training, and cultural competency in the workplace. However, we should be allocating equal time and resources to surveying the institutional climate, discussing concrete policies around dealing with discrimination, and building a supportive community around those most often on the receiving end of biases, both implicit and overt.

In a recent meeting with a mentee who is applying to medical school, we discussed this topic over coffee. She reminded me of the lyrics from Janelle Monáe’s song, Queen, in which she states, “Add us to equations, but they’ll never make us equal.” It is true — although we’ve made impressive strides in adding more URM physicians to the equation, we’ve got a ways to go in terms of making those physicians equal.

October 4th, 2018

Diapers During Residency

Cassandra Fritz, MD

I had the fascinating experience of interviewing for residency at 20+ weeks’ pregnant. Although a number of people told me that I was doomed, I found the experience to be quite enlightening. Since I couldn’t hide the fact that life outside medicine was going to be important to me during residency, I felt empowered to ask the “don’t ask” questions during my interviews. What did I have to lose? The perk of interviewing while pregnant was that it was very apparent which programs were going to be supportive of work-life balance and which programs were trying to wish away my protruding belly. This experience helped me to determine where I was going to have the most support, academically and personally.

Some people find the thought of having children during residency unimaginable, but a growing number of us not only contemplate having children while in training, but decide to take actually the plunge into changing diapers. Pregnancy during residency is not a new concept. In 1986, a study reported that 12% of women from Harvard-affiliated programs had at least one pregnancy during residency training (N Engl J Med 1986; 314:418). Jump forward to 2013–2016, when another study showed that approximately 40% of residents had or were planning to have children during residency (Acad Med 2016; 91:972). Although diapers during residency continues to gain traction, residency programs have a paucity of standard guidelines that outline how to best support residents with children. So, do residents feel like they are blazing a new trail at their program if they decide to have children?

Some people find the thought of having children during residency unimaginable, but a growing number of us not only contemplate having children while in training, but decide to take actually the plunge into changing diapers. Pregnancy during residency is not a new concept. In 1986, a study reported that 12% of women from Harvard-affiliated programs had at least one pregnancy during residency training (N Engl J Med 1986; 314:418). Jump forward to 2013–2016, when another study showed that approximately 40% of residents had or were planning to have children during residency (Acad Med 2016; 91:972). Although diapers during residency continues to gain traction, residency programs have a paucity of standard guidelines that outline how to best support residents with children. So, do residents feel like they are blazing a new trail at their program if they decide to have children?

If you decide diapers are going to be in your near future, here is some advice:

- Be organized! ’Cause mama doesn’t have time not to be

You will be wearing many hats: resident, mommy/daddy, wife/husband/partner — and all of these roles will require  your attention. My personal secret was to compartmentalize my life as much as possible. When I was home, it was family time until my kids went to sleep. While I was at work, I focused on work. But compartmentalization doesn’t get you out the door on time in the morning, organization does! Our family has a routine, and we live and die by that routine. When I walk in from work each day, I don’t pass go until bottles and lunches for the next day are prepared. Organization at home will allow you to be efficient, on time, and present at work.

your attention. My personal secret was to compartmentalize my life as much as possible. When I was home, it was family time until my kids went to sleep. While I was at work, I focused on work. But compartmentalization doesn’t get you out the door on time in the morning, organization does! Our family has a routine, and we live and die by that routine. When I walk in from work each day, I don’t pass go until bottles and lunches for the next day are prepared. Organization at home will allow you to be efficient, on time, and present at work.

- Don’t be afraid to ask for help, because the only way to do it all is with A LOT of help.

I am blessed that I have a great support system around me. If I know my schedule won’t allow me to pick up my kids from daycare at a reasonable time, I have a list of people who are happy to spend time with my boys. I don’t worry about how this looks to outsiders, or the fact that I probably have the longest list of people on my “approved for pick up list” at daycare. Who cares? What is important is that my boys are well cared for and loved. Having a strong support system means that I rarely have to call off from work because of child care issues. Because, let’s face it, we still work in an environment when “mommy issues” at work are frowned upon. Although it was initially hard for my type A personality to let go and ask for help, it is the only way to have it all.

- Advocate for yourself: Understanding the difference between equity and equality is imperative

Traditionally, I think we fall into a trap where we think that everything should be equal. If resident A gets a thing, then so should resident B. But in truth, maybe resident B doesn’t need what resident A needs. We need to move to a system that values equity over equality. This is not intuitive, so when you are resident parent, you must be your own advocate. You are inevitably going to have different concerns than your co-residents who don’t have children and/or significant others. There was one point during my intern year when my husband was traveling for work, and I made it a priority to pick up my son from daycare on time each evening (other than call days). Although my rush to get out of the hospital at the end of the day could have been seen as a negative, I had a co-intern and a senior resident who were extremely supportive, because I communicated with both of them what my needs were that week. Obviously, I always got my work done, but our team dynamics were improved because our open lines of communication were open. Fast forward to my second year, when another co-resident fell ill and needed coverage during an ICU month: I happily volunteered to cover his shifts. When you and your program focus on equity over equality, everyone can get what they need to be successful. It really does all balance out.

Traditionally, I think we fall into a trap where we think that everything should be equal. If resident A gets a thing, then so should resident B. But in truth, maybe resident B doesn’t need what resident A needs. We need to move to a system that values equity over equality. This is not intuitive, so when you are resident parent, you must be your own advocate. You are inevitably going to have different concerns than your co-residents who don’t have children and/or significant others. There was one point during my intern year when my husband was traveling for work, and I made it a priority to pick up my son from daycare on time each evening (other than call days). Although my rush to get out of the hospital at the end of the day could have been seen as a negative, I had a co-intern and a senior resident who were extremely supportive, because I communicated with both of them what my needs were that week. Obviously, I always got my work done, but our team dynamics were improved because our open lines of communication were open. Fast forward to my second year, when another co-resident fell ill and needed coverage during an ICU month: I happily volunteered to cover his shifts. When you and your program focus on equity over equality, everyone can get what they need to be successful. It really does all balance out.

At the end of the day, if you are ready to become a parent, don’t let residency stop you. If you are in the special position of choosing a program while expecting a child, ask those “don’t ask” questions during your interview to gauge programs’ receptivity to resident parents. I promise you, they will show their hand.

Some might say I am too positive and naïve, but I think we can do it all (with a lot of help and the “right” supportive program). When you are a doctor, there is never going to be a “best” time to have children. Finding and doing what makes you happy both in and out of the hospital is an important aspect of developing resiliency and experiencing joy during these 3 hard years. Although you will laugh when non-parent residents complain about sleep deprivation, you will also find that babies can teach you a lot about yourself and keep you grounded during this journey. Personally, my boys brought me so much joy during my training years that I truly can’t imagine doing residency without changing diapers. So, as far as my personal belief about changing diapers during residency: do it well and do it often because no one needs a “blow out” right before walking into rounds.

September 25th, 2018

Medicine-Induced Metabolic Syndrome

Justin Davis, MBBS

I run a clinic a couple of times a week as part of my nephrology training here at Barwon Health. I love my clinic. In addition to enjoying the longitudinal follow-up of patients and the relationships you build with them (one of the quintessential things that drew me toward physician training, and nephrology in particular), I like that it is rather varied. On any day, I might be dealing with relapsing glomerulonephritis, seeing one of our long-term haemodialysis or transplant recipients, or managing something like recurrent renal calculi. But far and away, the biggest number of patients that we see are those with chronic kidney disease (CKD). CKD is an interesting beast. While you get occasional cases that occur after severe acute kidney injury or are associated with a single kidney or perhaps obstructive uropathy, most CKD cases occur in people who are lumped into the category of “renovascular disease/diabetic nephropathy” — a nebulous miasma of patients who, more often than not, have raging metabolic syndrome or at least a whole bunch of cardiovascular risk factors that presumably have driven their CKD.

And, it was seeing these patients in clinic — these patients with obesity and relentlessly progressive CKD and a multitude of other chronic, incurable issues — that made me reflect on my own metabolic health. And while I don’t want to sound pejorative, it also made me vow to never turn out like them. I don’t want to be the overweight chap with uncontrolled diabetes who is sitting opposite the specialist. But what I want to touch on in this post is exactly that – how easy it can be to fall into that downward metabolic spiral, particularly with a job like ours.

Let’s all sit down for story time with Uncle Justin. I love playing basketball. I have loved it since I started in … what? Under 9s? Under 10s? (Somewhere around there). I’m tall, lanky, and completely uncoordinated, which makes me a terrible basketball player, but I still enjoy getting out there and running about (and the team aspect of it). Back in medical school, I was playing on three different teams a week (including one with the other medical students, called Rebound Tenderness, which is simultaneously the dorkiest and best name for a medical school basketball team ever). This was my major form of sport and activity, and it kept me in reasonable fitness for the 15+ years that I played.

Then something happened. That something was the physician’s exam; specifically, the written component of the exam. Suddenly (although “suddenly” is the wrong word, given you have well over a year to prepare and study, but I think it encapsulates just how disruptive that exam is to your life and schedule), I was heading to lectures that were broadcast by the Royal Australian College of Physicians every Thursday evening. (I’m aware I could have watched them later, but I wouldn’t have (a) paid attention or (b) learnt stuff that way. It’s just how I am.) Thursday was my one remaining basketball evening (the others having been whittled down slowly by demands during my intern and residency years). And just like that, I went from being a reasonably active kind of guy to doing no exercise and slaving over a computer. I wrote over a million words for this exam during the course of a year — the number of hours I put into it is kind of staggering. I was studying late, working long hours, and eating poorly. That, naturally, is a recipe for the kind of unhealthy lifestyle and diet that I like to call “the medicine-induced metabolic syndrome.”

A typical night at the RACP lectures, me being the only person there studying, happily watching (and clapping, apparently) alone.

It was just after the written exam when I realised just what the sequelae of study and work with no exercise had done to me. I had just come off my intensive care unit rotation, which I found exceptionally challenging, both because of the unique work involved and the nasty hours. (Physicians are not a critical care–trained specialty in Australia. I can happily work up a patient with raging lupus nephritis, but ask me which vasopressor to use next or how to fiddle with some ventilator settings, and you’ll likely just get a blank look from me.) The paradigm of 7-day, 12-hour shifts, week on– week off, plays absolute havoc with your circadian rhythm, particularly if you’re using energy drinks (like I was) to stay awake during the long nights and then spending off weeks doing nothing but study for an exam.

And so, just like that (although really, it was the consequence of the previous year of little exercise and an unhealthy diet), I had put on 10+ kg (I have no idea how many pounds this translates to, for our American audience. [Consults Google.] Ok, it’s about 22 pounds.) Although I was still a tall and (now, slightly less) lanky guy, most of that extra poundage had sneaked its way directly onto the stomach region — you know, the exact area that poses the highest metabolic risk, and where you don’t want extra adiposity.

It was a surprising wake up call, one that is echoed every time I’m in clinic with patients who have raging metabolic syndrome (and there are a lot of those people). Because I can understand how easy it is to fall into that trap. For me, it is associated with the particularly in the high-stress environment that calls itself medicine and with studying for the once-a-year, high stakes exam that you must pass. Why would I waste an hour running when that hour could be used for study? It’s the pitfall that causes medicine-induced metabolic syndrome – we need to look out for our own health, too.

How could you not want to go for a run around my hometown of Geelong, when it offers up views such as this?

I’m thankful to my fiancée (for this and many other reasons), because she encouraged me to eat better, and I started to run with her, which I’ve found is a fantastic way to stay active and avoid the dangers of the work/study black hole. I’ve figured out that running also is a great way to fit in the video game podcasts I enjoy listening to (and when else would I have time to listen?) I’m much healthier than I was at this time a couple of years ago. I’m currently 15 kg down (33 pounds, for our imperial system friends) from where I was right after the written exam, and that’s a good thing. Because I don’t want to be that guy on the other side of the doctor’s desk with unchecked metabolic syndrome, if I can help it. I just wish I had thought about that while I was studying.

“Do not allow the quest for knowledge to become paralytic. Only through action can you iterate on your belief.”

* The quotes from the unnamed source continue for my own amusement. Although I understand a few people have Googled it to come up with the answer.