August 17th, 2011

Transition — A Note from the Journal Watch Editors

Charleen Hamilton

First, Journal Watch would like to thank Dr. Greg Bratton for helping us to establish our Chief Resident blog. Greg has moved on to a Sports Medicine fellowship, but we’ll try to convince him to post his most interesting cases and insights as he continues his medical training.

Second, we’re very happy to announce that Dr. Gopi Astik and Dr. Heidi Zook, Chief Residents in Internal Medicine at the University of Missouri–Kansas City, will be our new bloggers. Starting in September 2011, Gopi and Heidi will offer their insights on the medical education experience and the challenges that residents and students face in incorporating evidence-based medicine into practice.

Finally, Dr. Sarah Lewis Bergman, a Senior Resident in Pediatrics at Seattle Children’s Hospital and a member of the Journal Watch Pediatrics editorial board, has kindly agreed to provide us with a taste of what life is like in this very important primary care field. She’ll be writing for the rest of the summer about her patients and experiences.

Please feel free to correspond with any of our resident bloggers by using the Comments feature at the end of each post.

August 4th, 2011

The End …

Greg Bratton, MD

I did it. I graduated.

I remember in sixth grade writing a paper about wanting to grow up to be a doctor, and today, I can truly say, “I did it.”

Graduating from residency, beginning my fellowship, and completing my Family Medicine board exam has made me feel as if I have finally put the punctuation at the end of this journey’s sentence. And despite having 12 more months to learn and refine my skills in Sports Medicine and another board exam on the horizon, I feel free. Free from the feeling of swimming upstream, free from the fear of not making it, and free from not seeing the light at the end of the tunnel.

Graduating from residency, beginning my fellowship, and completing my Family Medicine board exam has made me feel as if I have finally put the punctuation at the end of this journey’s sentence. And despite having 12 more months to learn and refine my skills in Sports Medicine and another board exam on the horizon, I feel free. Free from the feeling of swimming upstream, free from the fear of not making it, and free from not seeing the light at the end of the tunnel.

I know I will face more adversity, self-doubt, and obstacles in the future, but, right now, I am enjoying this feeling of accomplishment. For the first time in a long time, I can take a deep breath and relax.

However, I have to ask myself, “Why was the journey so hard and stressful?” Is it because I am a Type A personality that can make a massage stressful? Is it because the relationship medicine and I have is similar to that of a square peg and a round hole? Or is it because it really is just that difficult? I believe the latter.

So, in an effort to help ease the journey for others, I have compiled a Top 10 list of things I think can make the path to being a doctor a little more enjoyable and/or tolerable.

Here we go…

10. In college, major in something other than pre-med. You will learn enough science in medical school. Choose something like art, philosophy, or dance. It will expand your mind, and you will become well rounded and able to communicate with patients on a “natural” level.

9. Remember that, ultimately, you are a person first and a doctor second. Patients will relate to you. They will trust in your treatment plans and adhere to your recommendations. Find time to decompress. Take weekends off. Schedule date nights. Get involved with charities. Go fishing. Do something to keep in touch with who you are as a person. Don’t let medicine define you. You were John Doe before medical school, be John Doe after.

8. Date. Get married. Have children. Some say that it is too much to handle with studying, it is too expensive, or it is “just not the right time.” I disagree. I think it makes you better. Plus, no matter how hard of a day you’ve had or how grueling your week is, when you get home, someone is there to take your mind off of it. As a buddy of mine said after having his first son, “there are no more bad days.”

7. Read gossip magazines. After hours of memorizing Robbins Pathology or Grey’s Anatomy, you’ll need something to purge your brain. And what is better than keeping tabs on Lindsay Lohan, Britney Spears, and all the other train wrecks in Hollywood?!?! In addition, it will help you understand the many psychiatric problems you will one day be diagnosing and treating.

6. While at dinner, no matter how many of your classmates or fellow residents are present, DO NOT TALK ABOUT MEDICINE!! It always happens — you go out for a relaxing evening and inevitably start talking about work. Don’t do it! It is not fair to the non-medical professionals listening. Instead, talk about sports, weather, or the latest happenings in US! Magazine (another reason #7 is so important).

5. Periodically, wear normal clothes. I think we all will agree that one of the benefits to working in a hospital is the that you can wear scrubs every day. But remember, scrubs are forgiving; they won’t let you know that you’re not tying the drawstring as tight as you used to. Whether you weigh 150 lbs or 180 lbs, you are still going to wear the same size scrubs. Put on your jeans — they will tell you the truth about your circumference.

4. Exercise. Endorphins are good. Plus it will counteract the late night Cheetos, pizza, and soda consumed while being on-call or studying. And before you say it, there is always time! Just find it.

3. Call home. Talk to your mom and dad, brother and sister, hometown friends. Just because you’re “in medical school” does not mean you get to stop being their son, sibling, or friend. They are your support. Use them, lean on them, involve them. And remember, you are where you are because of them.

2. Keep an open mind while doing 3rd-year rotations. Even if you think you know what you want to do, don’t force yourself to like it. Enter each rotation with an open mind. Go with your gut. I wanted to do orthopedics but found myself “tolerating” the OR, not loving it. Yet, I loved taking care of families, seeing the same patient routinely, and developing relationships with patients. So I chose Family Medicine. Had you told me during my 1st or 2nd year of medical school that I would end up doing primary care, I would have laughed at you. But I love it and can’t imagine doing anything else.

1. Take a deep breath and relax occasionally. Don’t be like me and wait until you receive your diploma to re-center yourself. Do it daily. Know that although the journey is long, it doesn’t have to be rushed. Enjoy the moment. Enjoy the challenge. Realize that you, too, are on your way to achieving your dreams.

And, before you know it, your graduation day will be here.

The next chapter is frightening, but I’m ready, and you will be too. I don’t know where I will practice, what the government has in store for primary care, or how medicine will evolve, but it really doesn’t matter to me much right now. Today, I am happy. Today, I am free.

I did it. I graduated.

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading about my thoughts and experiences during the last year. I’ve definitely enjoyed sharing them.

Greg Bratton

July 7th, 2011

The Price of Being a Doctor

Greg Bratton, MD

I saw a patient while I was moonlighting the other night that actually made me question whether or not it was worth it to be a doctor.

The patient was a 56-year-old gentleman who presented to the emergency room complaining of neck pain. When I went to talk with him and learn more about his complaint, he told me that he had a history of neck pain and felt as if it was about to start “rebounding again.” He had no previous or recent injury to his neck, never underwent radiographs, and had no neurological symptoms, but some physician somewhere had felt it was appropriate to give him hydrocodone, and he had been treating his pain “effectively” with this medication ever since. He was taking no anti-inflammatories, had never seen a physical therapist, and had taken no other conservative measures to manage his pain. In fact, he had no primary care physician at all.

As we talked, it became blatantly clear that his “rebounding pain” was running in direct correlation with his dwindling hydrocodone prescription. I readily admit that I believe we, as a whole, under treat pain (for fear of inducing potential addiction, tolerance, and side effects), which is a disservice to our patients and their quality of life. However, as a sports medicine physician, I see my fair share of chronic musculoskeletal pain and, therefore, am comfortable with my treatment algorithm and with who qualifies for narcotic medications.

This guy did not require narcotics.

In further discussing his condition and my medical opinion that he needed to treat the ailment rather than masking it with pain meds, he became agitated (as you could imagine) and demanded hydrocodone. “I need hydrocodone 10/325 and I need a quantity of 30,” he emphatically stated. “It is the only thing that works.”

In further discussing his condition and my medical opinion that he needed to treat the ailment rather than masking it with pain meds, he became agitated (as you could imagine) and demanded hydrocodone. “I need hydrocodone 10/325 and I need a quantity of 30,” he emphatically stated. “It is the only thing that works.”

At this point my patience was wearing thin. Not only was this patient misusing the medical system by arriving at an emergency department for what appeared to be a medication refill, he was now attempting to bully me into prescribing him medication I did not feel was medically necessary. To make a long story short, I told the patient that this was not a negotiation and that I was going to treat him no differently than I treat any of my other patients. I stayed true to my clinical criteria for prescribing narcotics, and he left with a script for Mobic.

I was later informed by my nurse that, as he was leaving, he turned to her and asked, “What night does that doctor not work?” as if he was plotting his next attack.

I went back to my desk, irritated, and reflected about how I spent 4 years of medical school, incurred a large amount of debt, trudged through residency, sacrificed family time to extend my training through moonlighting, paid big bucks to take a board exam — not to mention the cost of licensing, DEA, and DPS numbers — and how it was all just lost on this patient because I was expected to do what he wanted.

And to be quite honest, it pissed me off.

There are people in our communities that have capitalized on physicians’ fears of litigation and willingness to practice defensive medicine to get what they want. They feel entitled when they are seen by a doctor. They “know” what is medically best. They aren’t coming to their appointments to get evaluated and treated, but rather, they are using the doctors as suppliers. They are successful because they instill a sense of “if you don’t do what I want, I will report you for failure to treat my pain adequately.”

And if this is how practicing medicine is going to evolve (insert political commentary here), then is it still worth it to be a doctor??

I had this question answered for me on Easter Sunday. I was enjoying a nice Easter service with my family. I had just returned to my pew after communion when, from the back of the sanctuary, a hysterical mother called out, “Is there a doctor in the house!?!?” A silence fell over the congregation and everyone stood frozen in their place — except for me. I arose from my pew and made my way to the mother.

As I approached the woman, I found her 14-year-old daughter lying horizontal on the wooden pew, pale and diaphoretic, with a confused and scared look on her face. She had passed out and was just awakening when I arrived. With the help of some other providers, we tended to the young girl, comforted the mom, and handled the situation appropriately.

Thankfully, the mother’s call for help was for something minor, but, to me, it was a major boost to my failing sense of purpose. To have my “name” called in a moment of personal despair and to realize that, in a gathering of 300 or more people, I was the only physician, made me feel as if being a physician still was something special.

So, is it worth it??

Yes, it’s priceless.

May 19th, 2011

Practice-Changing Articles V

Greg Bratton, MD

Recent advances and discussions in medicine are the cornerstone of Journal Watch. Here’s the fifth installment of the articles that made the biggest impression on me in the past 2 weeks. I hope you enjoy the articles I selected.

Please feel free to leave a comment on the articles — Do you like them? Dislike them? Agree, disagree, state your opinion, and participate in the discussion. And if you know of another recent interesting article, post a link to it. I would love to read it.

Greg Bratton, MD

Articles of Interest:

Physicians Recommend Different Treatments for Patients Than They Would Choose for Themselves – This interesting article brings the dreaded question, “What would you do, Doc?” to the forefront. We have all been asked how we would proceed in a given situation. This article suggests that our answers are not always truthful. A group of primary care physicians were presented one of two hypothetical clinical scenarios. One scenario involved choosing between two treatment options for colon cancer, and the other asked about two treatment options for avian flu. For the two treatment options in each scenario, one had a high rate of side effects but low risk for death, and the other had a low rate of side effects but a higher risk for death. In analyzing the data, in both scenarios, a large percentage of physicians chose treatments with higher risk for death for themselves, but only offered them to their patients between 25% and 50% of the time. Which begs the question, “Are we, in fact, treating our patients like we would our mother??”

Physicians Recommend Different Treatments for Patients Than They Would Choose for Themselves – This interesting article brings the dreaded question, “What would you do, Doc?” to the forefront. We have all been asked how we would proceed in a given situation. This article suggests that our answers are not always truthful. A group of primary care physicians were presented one of two hypothetical clinical scenarios. One scenario involved choosing between two treatment options for colon cancer, and the other asked about two treatment options for avian flu. For the two treatment options in each scenario, one had a high rate of side effects but low risk for death, and the other had a low rate of side effects but a higher risk for death. In analyzing the data, in both scenarios, a large percentage of physicians chose treatments with higher risk for death for themselves, but only offered them to their patients between 25% and 50% of the time. Which begs the question, “Are we, in fact, treating our patients like we would our mother??”- Cardiac Troponin: Lowering the Threshold, Improving the Outcome – In an attempt to make sense of mildly elevated troponins in the ER, researchers examined plasma troponin concentrations (<0.05 ng/mL, 0.05–0.19 ng/mL, and 0.20 ng/mL) and the clinical outcomes of those with suspected acute coronary syndrome. When the diagnostic threshold for troponin was lowered to 0.05 ng/mL from 0.20ng/mL, the rate of death or MI decreased. Ultimately, I believe if ERs adopt a lower troponin threshold for ACS criteria, we might improve morbidity and mortality, but at a cost of more interventions and hospital admissions and greater patient risk.

- Treating Sepsis in the Emergency Department Is Cost-Effective – This study hits home for me, as our ICU attendings at JPS Hospital currently are investigating sepsis and early goal-directed therapy (EGDT). Seeing that EGDT was associated with a gain of 1.3 quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) per patient at a cost of about $5400 per QALY suggests that EGDT was cost-effective (probability, >98%). And, with sepsis being one of the most serious and fatal diagnoses among patients admitted to hospitals, having a protocol to identify and treat it expediently will revolutionize emergency medicine centers.

May 13th, 2011

A Change of Heart

Greg Bratton, MD

It has been 18 months since I last lifted a dumbbell, ran on a treadmill, or attempted anything else to tune my body. In my own defense, I didn’t stop working out because I was lazy; in fact, quite the contrary. Truth is, 18 months ago, my son was born, and, since then, I couldn’t justify spending an hour more away from him than I needed to.

So, over the last year and a half, you could say I became a bit “soft.” Soft around the mid-section; soft in my dietary choices; and soft in my commitment to a healthy lifestyle. Chicken nuggets, macaroni & cheese, donuts, and French fries are so hard to turn down when the precious little hand of your son is feeding them to you, and you see the smile on his face every time you take a “dinosaur bite!”

But, if I have learned anything over the last 6 weeks of working in the ICU and on the Cardiology service, it is that dinosaurs are extinct, and I will be too if I don’t start changing my ways.

Specifically, over the last 2 weeks, I have seen four patients my age (+/- a year or two) who suffered heart attacks and required intervention. Let me be clear here, I saw FOUR patients in a span of 10 days who suffered non-fatal MIs not far from their 32nd birthdays!

One patient I am caring for is a 63-year-old gentleman who also recently suffered a heart attack and subsequently received angioplasty and stent placement. He had no risk factors, no family history, and was not obese. He simply awoke one day with chest pain and decided to get it checked out. Thank goodness he did, because he had near- complete blockage of his left anterior descending artery.

When we rounded on him this morning, he was sitting at his bedside alongside his wife, full of life and with a notebook full of questions. As my attending began to debrief him on the recent events and procedures that were performed, I could see his mind going into overdrive trying to absorb all the information. When it came time for him to ask his questions, he scanned his premade list, took a deep breath, and asked, “How can I prevent this from happening again?”

When I heard this, like a cowboy had jerked on the reigns of a horse, my head perked up. For some reason, this fortunate man’s simple question struck a chord in me. Why should I wait until I am 63 years old and recovering from a heart attack to change my ways? Why should it take an adverse event to convince me that I need to live healthier? I am young and knowledgeable. I need to do it now, if not for me, then for my son and future children. I need to be healthy for them.

When I left work today, I turned over the proverbial leaf. Instead of heading straight home to sit on the couch and wrestle with my little man, I made a quick stop with longstanding benefits.

I joined a gym.

April 13th, 2011

Practice-Changing Articles IV

Greg Bratton, MD

Recent advances and discussions in medicine are the cornerstone of Journal Watch. Here’s the fourth installment of the articles that made the biggest impression on me in the past 2 weeks. I hope you enjoy the articles I selected.

Please feel free to leave a comment on the articles — Do you like them? Dislike them? Agree, disagree, state your opinion, and participate in the discussion. And if you know of another recent interesting article, post a link to it. I would love to read it.

Greg Bratton, MD

Articles of Interest:

Glycemic Control in Hospitalized Patients: Hold On Loosely? – A common topic on Medicine rounds – whether in the ICU or on the wards – is blood sugar. Likely, this is because of the preponderance of diabetics that require hospitalization. However, keeping tight control of their sugar in the hospital might not be as crucial as keeping tight control of it in outpatients. According to this study, intensive insulin therapy (IIT) “… did not improve short-term mortality (at 28 days), and no consistent evidence showed that long-term mortality (at 90 or 180 days), length of stay, or infection rates were better with IIT.” The major side effect of IIT was hypoglycemia, which might be associated higher mortality, dementia, and adverse cardiovascular events. The American College of Physicians have now recommended a target blood glucose level of 140 to 200 mg/dL while in the hospital. And suddenly, I hear nurses in the background scream in excitement as q4hr Accuchecks become a thing of the past!!

Glycemic Control in Hospitalized Patients: Hold On Loosely? – A common topic on Medicine rounds – whether in the ICU or on the wards – is blood sugar. Likely, this is because of the preponderance of diabetics that require hospitalization. However, keeping tight control of their sugar in the hospital might not be as crucial as keeping tight control of it in outpatients. According to this study, intensive insulin therapy (IIT) “… did not improve short-term mortality (at 28 days), and no consistent evidence showed that long-term mortality (at 90 or 180 days), length of stay, or infection rates were better with IIT.” The major side effect of IIT was hypoglycemia, which might be associated higher mortality, dementia, and adverse cardiovascular events. The American College of Physicians have now recommended a target blood glucose level of 140 to 200 mg/dL while in the hospital. And suddenly, I hear nurses in the background scream in excitement as q4hr Accuchecks become a thing of the past!!- Osteoarthritis of the Hip or Knee Raises Mortality Risk – During 14 years, 1163 patients who had symptomatic x-ray confirmed osteoarthritis of the hip and knee were found to have excess all-cause mortality compared with the general population. Similarly, they had excess cardiovascular-, cancer-, and dementia-associated mortality as well. Even as a Sports Medicine doc, I never really put 2 and 2 together when it came to OA. But, in reading this article, it all makes perfect sense. Patients with advanced OA limit their activity to limit pain. In doing so, they become “functionally sedentary,” which equates to increases in weight, cardiovascular risk factors, blood clots, and many other potentially dangerous conditions. In particular, the authors of this article speculate that less physical activity, smoldering inflammation, and use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs play a large part in mortality risk. This is definitely something I will implement into my daily discussions with patients about why it is important to address OA aggressively.

- Antihypertensive Treatment in Patients Without Hypertension – Although this was a technically limited study, an interesting approach is brought to light. We all know the benefit of anti-hypertensive medications when it comes to blood pressure and associated adverse events (stroke, MI, etc.). But using these meds in a population without hypertension in order to prevent these outcomes seems ridiculous. Or does it? In this meta-analysis of 25 randomized trials of antihypertensive medications, 64,162 nonhypertensive patients with cardiovascular disease (CHF, MI, CVA) or risk factors for CVD were studied. The outcomes showed “relative risk reductions for patients with known CVD were 23% for stroke, 20% for MI, 29% for CHF events, 17% for CVD-related mortality, and 13% for all-cause mortality.” The limitation being the number needed to treat to establish such reductions were 20-130 patients. There was no significant benefit when participants had only CVD risk factors. Whether lower-risk patients without CVD benefit from prehypertension treatment is less clear, but this study does raise some interesting questions. And as I always say, even a bonfire starts with a single flame.

April 7th, 2011

The Colors of Life

Greg Bratton, MD

For a week, the patient in bed 301 had been fighting.

After being found unresponsive and hypothermic in the field, this 48-year-old male was brought to the ICU and was treated for metabolic acidosis, end-stage liver disease, hepatic encephalopathy, and an acute upper GI bleed, all in the context of presumed alcohol intoxication/withdrawal. It was not until later that we discovered that, in conjunction with everything else, he had ingested a substantial amount of ethylene glycol, better known as antifreeze.

From what we could gather, he was a transient and had spent the last several years living in the streets and his family members’ couches. In fact, 3 months ago, he left his aunt’s house one morning and “disappeared,” not to be heard from or seen again. It wasn’t until we called the number in his chart to obtain collateral information that his family discovered his whereabouts.

He had a past medical history significant for hepatitis B andC but continued to abuse alcohol and other substances. As a result, his liver had been so severely damaged that he suffered from esophageal varices, recurrent ascites, and altered mentation. Now, as a result of his antifreeze ingestion, he had grade D esophagitis as well; hence his GI bleed.

While in the ICU, he was on a ventilator for respiratory failure, hemodialysis for acute kidney failure secondary to the ethylene glycol intoxication, pressors for hemodynamic instability, and serial paracenteses. And despite our best efforts, he simply did not improve. He failed multiple weaning trails from the ventilator and could not maintain his blood pressure without medication. We all knew early on that his prognosis was poor.

One night, while I was on call, I stopped by his room to see how he was doing. With the beep of an empty IV bag in the background and the timed inspirations and expirations of the ventilator blowing precisely every few seconds, I stood beside his bed and quickly realized that his prognosis had gone from “poor” to “fatal.” Sometime during the last hour or so, he had begun to bleed out of everywhere. His foley, rectal tube, endotracheal tube, and nasogastric tube were all full of blood; his central and peripheral lines had saturated their dressings. His body had gone into DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, a poor prognostic sign which carries with it 10%-50% mortality. Casually, DIC stands for “Death Is Coming.”

I quickly contacted family and advised them to come as soon as possible. For his mom, it meant driving 3 hours from Oklahoma. I assured her that I would do everything I could to keep him alive until she arrived, but I could make no promises. She said, “Please, do your best.” So we began to hang blood and clotting factors to try to limit his body’s destruction. The family arrived to bedside around midnight.

It was about 3 o’clock in the morning when I got the page from my nurse. After what had to be a very painful and difficult couple of hours, his family had decided to withdraw care. Out of respect for the family, I wanted to be present to answer any last questions and to show my support for their decision.

We extubated him, turned off the pressors, gave him some pain medication, and made him comfortable. Then, I left the room to allow his family to share in the moment privately, but sat outside within view of the patient, just in case.

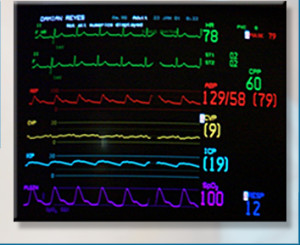

As I sat and waited for nature to run its course, I found myself staring at the monitor. This 20” black screen with a black background captivated me like nothing has before. I watched the red cardiac rhythm line, anticipating its demise to asystole. I watched the blue respiration line, waiting for it to cease making upward movements as his breathing failed. And I watched the green pulse line and rate number continue to fall toward zero. I was enamored with the little black box and all the information it was feeding me.

As I sat and waited for nature to run its course, I found myself staring at the monitor. This 20” black screen with a black background captivated me like nothing has before. I watched the red cardiac rhythm line, anticipating its demise to asystole. I watched the blue respiration line, waiting for it to cease making upward movements as his breathing failed. And I watched the green pulse line and rate number continue to fall toward zero. I was enamored with the little black box and all the information it was feeding me.

But then, out of the corner of my eye, I saw my patient’s mother, aunt, and brother, leaning over his bed, whispering caring remarks into his ear, holding his hand, and crying. They were doing everything they could to demonstrate to him their love and heartbreak. They ran their fingers through his hair, caressed his legs, and kissed his cheeks. It was a terrible, beautiful sight.

Suddenly, I realized that I had fallen victim to what happens to so many doctors. I stopped feeling. I stopped seeing Bed 301 as a person. To me, he was a critically ill patient that needed to have care withdrawn because Medicine told me he would not survive. I had accepted that he needed to die because his condition was deteriorating rapidly. What else could we, as doctors, do? Dump tons of blood and blood products into him, at the cost of depleting the blood bank and his family’s bank account and delaying the inevitable??

I forgot that he was someone’s son, someone’s brother, someone’s love. I forgot that even though Medicine told me he would not survive, it meant nothing to his family who relied on faith and miracles. I discounted that all his family wanted was a chance for him to survive. And I thought of my own son and family and, abruptly, the power and emotion of the moment became real to me.

I was affected that night.

I am nearing the end of my residency and, perhaps, have become jaded and skeptical and insensitive to many situations. I find myself doubting a patient’s pain level due to presumed drug-seeking; questioning the truth behind a patient’s story; and not giving a patient the benefit of the doubt when a treatment regimen fails.

What Bed 301’s passing did for me was reinforce to me that patients are not objects. Their conditions are not black and white. In fact, they are people, dynamic and colorful, just like the rainbow of colors bouncing on the monitor.

And, although I was focused on the right thing the night the patient in Bed 301 died, my context was way wrong. Those colored lines in the little black box represented life, not vital signs.

So, thank you, Bed 301, for reintroducing me to the colors of life. When I stop and look at them, they are beautiful.

March 22nd, 2011

Practice-Changing Articles III

Greg Bratton, MD

Recent advances and discussions in medicine are the cornerstone of Journal Watch. Here’s the third installment of the articles that made the biggest impression on me in the past 2 weeks. I hope you enjoy the articles I selected.

Please feel free to leave a comment on the articles — Do you like them? Dislike them? Agree, disagree, state your opinion, and participate in the discussion. And if you know of another recent interesting article, post a link to it. I would love to read it.

Greg Bratton, MD

Articles of Interest:

- Senior Match Day Results; Residencies Up In Pediatrics, Family Medicine – “Positions filled by U.S. seniors rose by 11% in family medicine … and family medicine matches were higher for the second year straight.” As a nation, the United States remains underserved in primary care, but it appears more medical students are willing to fill the gap. Once considered a cast-off specialty, Family Medicine residencies across the country are becoming more and more competitive, as evidenced by only 78 out of 453 programs not filling.

- Statins and Risk for Intracerebral Hemorrhage – In recent study of survivors of an intracerebral hemorrhage, findings suggested that statin use might be associated with higher risk for intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). “Statin therapy was predicted to increase the baseline annual probability of recurrence of lobar ICH from approximately 14% to approximately 22%.” Although statins are a drug with many benefits ranging from cholesterol lowering to anti-inflammatory actions to prevention of macrovascular complications in those with diabetes, this study raises a new concern. However, until a true randomized clinical trial can be performed, we must consider these findings.

Sterile Gloves to Obtain Blood Cultures? – Although it seems intuitive, a study published in the Annals of Internal Medicinereveals that the rate of positive blood cultures went down when sterile gloves were used. Mentioned in this review was the fact that the current guidelines from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute do not require the use of sterile gloves. From personal experience, making this small procedural change would save time, money, and potential antibiotic resistance by limiting the number of “coag-negative staph in clusters” found in routine blood cultures.

Sterile Gloves to Obtain Blood Cultures? – Although it seems intuitive, a study published in the Annals of Internal Medicinereveals that the rate of positive blood cultures went down when sterile gloves were used. Mentioned in this review was the fact that the current guidelines from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute do not require the use of sterile gloves. From personal experience, making this small procedural change would save time, money, and potential antibiotic resistance by limiting the number of “coag-negative staph in clusters” found in routine blood cultures.

March 15th, 2011

Match Day

Greg Bratton, MD

I was talking to the third-year medical student who was rotating on my Medicine service the other day about what type of medicine he thought he might end up practicing and, astutely, he said, “Family/Internal Medicine.” I raised my eyebrows. Shortly thereafter, he conceded with a chuckle that he wasn’t sure.

I was talking to the third-year medical student who was rotating on my Medicine service the other day about what type of medicine he thought he might end up practicing and, astutely, he said, “Family/Internal Medicine.” I raised my eyebrows. Shortly thereafter, he conceded with a chuckle that he wasn’t sure.

“I hope I figure it out soon,” he said. “It is really nerve racking.” I told him not to sweat it. I also told him that things would work out like they are supposed to and that one day he would wake up and just know.

When I went to medical school, I had no doubt in my mind that I was going to be an orthopedic surgeon and work with elite athletes. Coming off of a collegiate sports career myself, that’s all I knew. So for my first 3 years of medical school, I did everything I could to make sure that this would be my reality. I joined the orthopedic interest group and served as an officer; I did research; I schmoozed with the faculty to assure quality letters of recommendation; and I surrounded myself with orthopedic friends. I did everything I could be become a member of the fraternity.

But when I did my orthopedics rotation as a third year, I found that I enjoyed it, but I didn’t love it. I tolerated the operating room and the surgeries, but I never found myself getting excited about scrubbing in like I thought I would. Initially, I chalked it up to being a MS-III and not really being able to participate — other than to retract — and possibly to not having the best residents and faculty on my team to introduce me to the specialty. But as time went on and the ERAS application began to stare me in the face, I felt just like my medical student does now — scared about my future.

Daily, I would try to convince myself that things would be different in residency and out in practice; that I could learn to love the operating room; or that orthopedics was still what I was supposed to do. Then, one morning in late May of my third year, out of the blue, I awoke and saw things differently. As if I had decided in my sleep, my worries were gone and my mind was clear. I realized that I was not going to pursue orthopedics, but rather Family Medicine.

What!!?!?! Family Medicine?? Out of nowhere, I jumped ship from the specialty for which I had been grooming myself to primary care??

My only experience with Family Medicine was a 6-week rotation at the very beginning of my third year. Sure, I loved it, but I figured that was because it was my first rotation, and I was finally out of the lecture hall. Heck, I probably would have loved basket weaving at that time! When I analyzed my decision, a determining factor was the ability to have more consistent time with my family. With Family Medicine, I could coach little league, go to the school plays, and take my kids camping — things I couldn’t do if I was tied to the operating room. Plus, I could envision myself seeing patients in a clinic at age 50, but I couldn’t see myself in the OR at that stage of my life.

This week is “Match Week” for the 4th-year medical students. By Friday, these young physicians will be learning their professional fate. Whether they’re ready or not, they will open envelopes that will tell them where they will be spending the next 3 to 5 years of their life. And, if they are like I was, the anxiety of this moment is killing them because the future they were so scared of as third-year students will soon be reality. Their fear and anxiety now likely isn’t about making the right choice, but rather is about not getting into their number one choice, ending up living in the middle of nowhere, or of not matching at all.

However, on my Match Day, my fear and anxiety was centered around whether I had made the right choice by not pursuing orthopedics. Now, though, 3 years later, I am about to graduate from JPS as a Family Medicine physician, and I am happier than I could have ever imagined. And I can say without a doubt that I absolutelymade the right decision. Family Medicine has afforded me every opportunity that I want out of medicine. I think critically about medicine patients; I perform procedures ranging from colonoscopies to skin biopsies to joint injections to delivering babies; I develop relationships with my patients; and I get to see my family. I get to live the life that I always dreamed of!

So if I could talk to this year’s graduates, I would tell them what I told my third-year medical student, “Don’t sweat it. That things will work out like they are supposed to.”

Believe it or not, dreams do come true. Mine did. Happy Match Day!

February 28th, 2011

Practice-Changing Articles II

Greg Bratton, MD

Recent advances and discussions in medicine are the cornerstone of Journal Watch. Here’s the second installment of the articles that made the biggest impression on me in the past 2 weeks. I hope you enjoy the articles I selected.

Please feel free to leave a comment on the articles — Do you like them? Dislike them? Agree, disagree, state your opinion, and participate in the discussion. And if you know of another recent interesting article, post a link to it. I would love to read it.

Greg Bratton, MD

Articles of Interest:

Cribs, Playpens Pose ‘Unacceptable Level of Danger’ (and the original Pediatrics article) – Stories of children walking into their parents’ rooms one morning asking for breakfast after climbing out of their cribs could be a thing of the past. In a retrospective review of 19 years worth of emergency room data concerning injuries to children younger than 2 years, 80% involved cribs and roughly 2 in 3 involved falls, proving an “unacceptable level of danger.” So although using the baby crib you were raised in could save some money, maybe you’ll want to think twice.

Cribs, Playpens Pose ‘Unacceptable Level of Danger’ (and the original Pediatrics article) – Stories of children walking into their parents’ rooms one morning asking for breakfast after climbing out of their cribs could be a thing of the past. In a retrospective review of 19 years worth of emergency room data concerning injuries to children younger than 2 years, 80% involved cribs and roughly 2 in 3 involved falls, proving an “unacceptable level of danger.” So although using the baby crib you were raised in could save some money, maybe you’ll want to think twice.- Effects of Cell Phone Radio frequency Signal Exposure on Brain Glucose Metabolism – At some point, cell phones were going to be shown to influence our health (everything does). And although this study is cursory at best, it could be the match that lights the fire. Using a PET scan to show altered glucose metabolism in the area of the brain nearest the antenna – with no known consequence – this study does hint that cellular signals affect us on a physiologic level.

- Knee Replacement Surgery? AAOS Says Get Two At The Same Time – I get asked all the time, “Should I get both my knees replaced at the same time or one at a time?” Under normal circumstances, I advise them to consider their age, their support system at home, and their likelihood of going back for a second surgery. However, this study now provides a little more to think about. Published by the Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, it showed that replacing both knees at once versus in two separate procedures was associated with significantly fewer prosthetic joint infections but with higher risk for cardiovascular events, including pulmonary embolism and heart attack.