August 14th, 2015

The Answer

Ahmad Yousaf, MD

Ahmad Yousaf, MD, is the 2015-16 Ambulatory Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School.

“Please answer my call.”

That was the text I received over the weekend from a friend after having missed his call. I called back and he was panicked: “what is alpha… al… alteplase?” There was a pause as I waited for context… “My mother-in-law… she went into cardiac arrest. They got her heartbeat back, but they said she needs that medicine… should they give it?”

After hearing the context, I advised him that I thought it made sense — that they should give alteplase a try, given how critical the situation seemed. I hung up the phone. I had been sitting on a lawn chair in my backyard studying for the boards and, although I knew what the answer to this clinical question was on the ABIM, a feeling of uncertainty filled me. Without knowing what had just occurred on the phone, my wife saw my face and could tell something was wrong. I explained what was happening and that I needed to go to the hospital to be there for my friend.

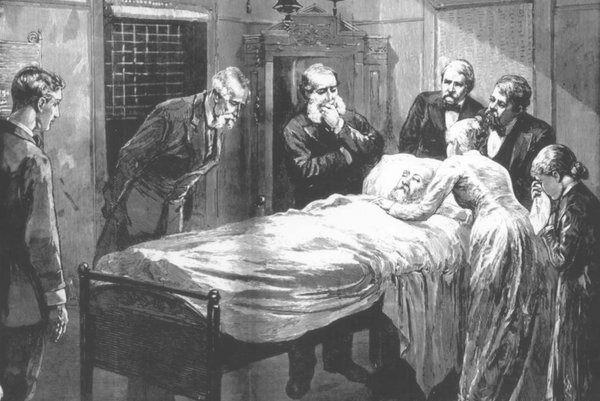

By the time I arrived to the hospital, the situation had deteriorated further. The patient’s loving family was in all stages of grief as their mother/sister/aunt held on to life with the support of pressors and a ventilator. I wanted to do something but knew it was not my place. I was a doctor in an alternate universe but today… today, I was just a friend. I gave a hug or two and awaited news on the status of the sweet woman who lay critically ill behind the ER curtain. She was the mother of 5 wonderful adult children, 2 of whom I have the pleasure of knowing. They are the type of people who never meet you without warm smiles and that ‘big-family’ type of love. On this day, however, I only saw pain in their eyes. I stood in the ER corridor with family I had never met and bowed my head and prayed with them.

An ER resident emerged from behind the curtain with a walk I was all too familiar with. He had bad news, and I could see his mind racing with the words that were going to be needed as he approached a large family who sat on the edge of hope and despair. The family collectively leaned forward as the resident fumbled with medical jargon like “coded,” pulmonary embolism, tPA, vasopressors, and futility. The eldest son frantically asked the questions on the mind of everyone except me: “What does all of that mean? Is she going to be okay?”

The resident took a deep breath and reworded his initial statement in an even less coherent manner. He was struggling. They were struggling. He concluded his ramblings with a request of clarification of code status and ‘DNR.’

It has always been a personal frustration of mine to see a physician drop a bad-news bomb on a family and, then, in the time of their biggest vulnerability, saddle them with the burden of a perceived ‘decision’ that never really existed to begin with. I put my hand on the shoulder of the resident mid-sentence and asked him to give us a few minutes. He gave me a look of relief and quickly escaped away to the sanctuary behind the nurse’s station. I have always felt comfortable delivering bad news and saying what needs to be said, but this day was different. I felt like a man between the two worlds of healthcare: the deliverers and the receivers.

She peacefully passed away about an hour later with her caring family around her. She was surrounded by their affection and prayers. I was a witness to their love and in awe of their display of absolute class and dignity. At one point, I absconded to my car and looked at the stethoscope and white coat that lay in the passenger seat. I concluded that so little of medicine had to do with those archetypal items that lay there and so much more of it with the intangible… The figurative space between a physician and his patient/family is full of that unquantifiable mixture of love, respect, fear, and worry. It is up to us to manage that space. That is our domain and our responsibility. The white coat… the stethoscope… the prescription pad… never has and never will be the answer.

~Yousaf

August 7th, 2015

Cat Herding

Gregory Shumer, MD

Greg Shumer, MD, is a third-year resident and 2015-16 Co-Chief Resident at the University of Michigan Family Medicine Residency Program in Ann Arbor.

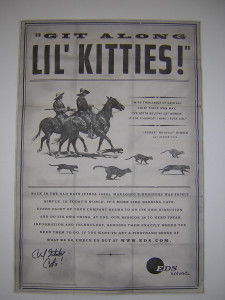

“The day you earned your MD, you became a leader… A leader to your future patients, a leader in your community, and a leader within the healthcare system.”It’s May 7th, 2015 – day 1 of the annual Chief Resident Leadership Development Program in Kansas City, Missouri. It’s an event meant to welcome the newly selected chiefs from family medicine programs around the nation and instill them with leadership skills and enthusiasm as they enter their third year of residency and chief years at their programs. The program’s director is delivering an introduction speech to his audience – roughly 150 bright-eyed chief residents, including myself and my co-chief, who traveled from across the country to be part of the 3-day conference.

“And as chief resident, you are a leader of leaders – not an easy task!” he continues. “Leaders are often independent and opinionated, and trying to direct an entire group of them is as easy as trying to herd a group of cats.”

“And as chief resident, you are a leader of leaders – not an easy task!” he continues. “Leaders are often independent and opinionated, and trying to direct an entire group of them is as easy as trying to herd a group of cats.”

He pushes a button on his handheld pointer, and a video begins on the big screen projector, showing images of rough-and-tough cowboys trying to circle up and direct large groups of small cats.

“Anyone can herd cattle,” one of the cowboys says as cats meow in the background, “but holding together 10,000 half-wild shorthairs, now that’s another thing altogether.”

We had a good laugh, and the chief conference was under way.

During our 3 days together, we learned that we all share common challenges. Scheduling conflicts are near the top of the list. Low morale and burnout are other common themes — attributed to long hours and the natural stress that occurs during residency. We also realized that family medicine programs across the country share several positive themes, such as the sense of community and teamwork that exists within programs, and the strong bonds that develop through working together at the hospital and in clinic.

We learned that as chief residents, we wear many different hats. In an average week, we serve as leaders, organizers, motivators, negotiators, problem solvers, teachers, and of course, third-year resident physicians in clinics and at the hospitals. Through Myers-Briggs personality testing, we discovered our different leadership styles. As an ENFP (Extroverted, iNtuitive, Feeling, Perceiving), I fall in the category of “idealist,” with strengths that include diplomatic persuasion and cultivating morale, and weaknesses that include an aversion to conflict and difficulty with setting limits for bad behavior. We learned about five leadership practices: model the way, inspire a shared vision, challenge the process, enable others to act, and encourage the heart.

By the end of the conference, I felt inspired and ready to take on this whole chief resident thing. I had been performing chiefly duties for about a month — dealing with scheduling conflicts, leading the annual residency retreat, participating in monthly meetings, etc — and it was the perfect time for this type of motivating and thought-provoking experience. Now, close to 3 months later, I think back to my time in Kansas City whenever I start to feel tired or overwhelmed.

July 1st has come and gone. The new interns arrived with their nervous smiles and freshly ironed white coats, and we all moved up a rung on the ladder. As a chief resident, the beginning of a new academic year brings new challenges. But it also allows for new and exciting opportunities — chances to serve as a resident advocate, to “model the way” for the interns and second-years, and to inspire positive change, little-by-little, day-by-day. Thankfully, my co-residents and faculty here in Ann Arbor make it rewarding and fun.

So, onward and upward. Cat herding — ain’t a feeling like it in the world!

July 31st, 2015

Do I Want My Daughter to Be a Doctor?

Raktim Ghosh, MD

Raktim Ghosh, MD, is a 2015-16 Chief Resident at St. Vincent Charity Medical Center, in Cleveland, Ohio.

It was not a very typical Saturday morning in Cleveland, at least not to us. My soon to be 1-year-old daughter woke up with surprise in her big doe eyes. That’s right… she woke up not in her nanny’s lap or in her crib, but in between both of her parents who were still sleeping. This was probably the first time since she started recognizing us that she found both of us beside her in the morning.I smiled at her. “That’s how it is supposed to be, dear, but your parents are still residents, they are budding physicians. Moreover, for you, my little munchkin, your mom and I split calls so that one of us can be with you, although that leaves us in a situation where we live together but don’t see each other for days. Now I can see the obvious question in your innocent mind, ‘why do you work so hard, mom and dad?’ I could give you a simple answer, like, to get you more toys.”

A sudden cold zing waved through my back and jolted through me this lazy morning. I asked the same question to myself… why did I choose this path? More than 12 years ago, when I started medical school on a different continent, I actually had to work harder than this to get there. I thought it would be cool to be in a profession that involves saving lives. I chose clinical pharmacology as my residency specialty because I felt I needed to know about drugs that can cure suffering people. After I finished residency, I decided that my path wasn’t good enough. Call me ambitious or an overachiever! But the reality was, that feeling was chasing me. The decision to leave my country, my parents, and an established career was not easy. Now, when I’m in the final year of my second residency, have become a chief resident, and have almost started seeing the glimpse of light at the end of the tunnel again, part of me is back to asking hard questions. “That’s it? Or shall I go for subspecialty training?” I don’t know the answer yet. The only truth is ‘miles to go before I sleep.’ The primary reason I chose to apply for chief residency was to teach and give back to my juniors what I have learned so far. This is the most satisfying part of practicing medicine to me — being intellectually challenged every morning. However, this ambition takes away a few extra hours from my daughter’s play time, as daddy is still busy with his Ipad after coming home from work. I’m now used to switching between UpToDate and YouTube Baby Songs while she sits on my lap. But, it’s the rare Saturday morning that the three of us wake up together.

I never felt bored during my long course of training. Physically, I was tired at times, but mentally, I was never fatigued. It gives me feeling of extreme accomplishment and happiness when I see my patients can connect to me. They want to come back and see me again even when they’re not sick. This liaison keeps me going. There is no better feeling than throwing some rays of hope into some hopeless eyes. Even when I have lost the track at times, my teeny tiny, but extremely strong, girlfriend-turned-wife and now mother of my child stood by me like a lone cypress for last 15 years. She has been my pillar of strength in my topsy turvy roller coaster ride, and undoubtedly, she’s the woman who made me what I’m today.

So I come back to the eternal question, “do I want my daughter to become a doctor?” Of course, I want her to make her own choice at the end, but my answer is YES. Because I think there is no better way to live than to feel content at the end of the day for what you do. I do sleep well at night, not because I am tired, but because I am happy.

July 24th, 2015

Heroes Do Exist

Ahmad Yousaf, MD

Ahmad Yousaf, MD, is the 2015-16 Ambulatory Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School.

We live in a time of great cynicism and skepticism. We seem to see only the mundane and boring in even the most interesting and spectacular things. The electrical rhythm of the heart that pulses through cardiac tissue and results in a coordinated muscle contraction that effectively ejects blood to the rest of the body for appropriate oxygen delivery is just… a bland grouping of chemical/physical terms that relay information, without the awe that should accompany it. Perhaps it is the overload of data hurled at us from all different technologies that make everything seem ‘blah.’ Or maybe the cultural barrage of the age of ‘enlightenment’ that comes with modernity has left us so intellectually arrogant that we refuse to allow our hearts and minds the satisfaction of wonderment. Either way, it is as though we have lost the ability to appreciate the magnificence of existence around us and we have instead replaced it with dull expectation and assumed banality.

I was recently watching a debate between a few friends about which comic book superhero had the most depth. One of my friends claimed Batman was the most layered character, and his reasoning was as follows: Bruce Wayne was actually the costume and he was only himself (in his own voice and character) when he donned the Batman suit and cape. Anytime he was Bruce Wayne to the people of Gotham, he was just acting and putting on a show. It was only when he was Batman that we could see what the real man was all about. I mulled over the argument in my mind and could not help but think of the child-like awe comic book heroes still elicit from me, even as an adult. I thought: “Could it be that the heroes I adore are all around me already in suit and cape?” I began to think of the men and women that have affected how I think, act, and work.

There is the one physician who carries so much medical knowledge in his superhuman mind that he nullifies the suspense of case conference by simply stating the rare diagnosis before anyone else can even process the differential. And the one doctor whose very intellectual prowess can result in the collective anal sphincter tightening of an entire intern class… And one whose eyes are surrounded by dark circles formed over a multitude of sleepless nights as he mulled over what else he could do for his ill patient. They all don their capes every day. The ICU doctor who conveys bad news like soft kisses or the one who seems to restlessly pace the halls of the cancer ward deep into the night like a vigilante there to stomp out any chance of pain and misery. There is the doctor who has been serving long enough to walk the corridors like a sentry, protecting the hospital from inappropriate care or unneeded costs. They move among us and look like us… but they are so much more. They are what we aspire to be. The one who doles out chocolate like justice or the one who holds the weight of the academic program solely on his shoulders. They uphold the honor and dignity of a profession that has turned to bitterness, misanthropy, and the bottom line. They live for this. For their patients. For their Robins. They are the heroes we need, if only we could see past the darkness of our preconceived notions of medicine. They are there. On the proverbial rooftops of our hospitals… watching over us… teaching us… making sure that someone is ready to replace them when they are gone.

But then, they remove their white coats and return home to their families to continue their ‘normal’ lives as they try to convince the world that they are but mere mortals like the rest of us.

~Yousaf

July 17th, 2015

Good Luck! You Will Be Great!

Nicole Hugel, MD

Nicole Hugel, MD, is a 2015-16 Chief Medical Resident at University Hospital in London, Ontario, Canada

July 1st, the date of new beginnings in medical training. This is the day where we first get to use the title “Doctor,” start our first senior-level call, become subspecialty fellows, or finally reach the end of residency and formal clinical training. For me, July 1st marked the first day in my role as Chief Medical Resident (CMR). In my program, the CMR position is shared among six residents across two teaching hospitals. We have both teaching and administrative responsibilities, and, like most other CMR positions in Canada, we complete these alongside our regular clinical rotations.

Since discovering that I would get to be CMR this year, I have felt a mix of excitement and insecurity. I would go to sleep confident that I could excel in this position, then have nightmares that I would get in front of the whiteboard for a teaching session and completely forget everything I had prepared. As July 1st got closer, I got increasingly nervous.

Insecurity as I take on new clinical responsibilities is definitely not a new experience for me or for most other trainees and residents. As we progress through medical training, we are torn between feeling ready for more independence, and being worried we have not learned enough to complete more difficult medical assessments. These same feelings hit us with our first unstable patient, first time running a code, and first time on senior-level call. We are eager to make our own decisions and then second-guess every decision we make.

Part of this insecurity is a safety mechanism, and it helps motivate us to learn and make better clinical decisions. But, as residents, we need reassurance that our insecurity is normal. Mentorship is a huge part of building a career in medicine, but I find it especially important when moving toward additional clinical or administrative responsibility. Our mentors normalize our apprehension and build our confidence. They share their own successes and failures, and remind us that we are not alone in the challenges we face.

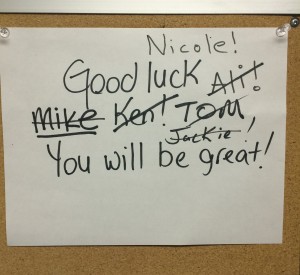

On June 30th, I was acutely aware of the big shoes I had to fill as CMR. The former CMRs have been wonderful teachers and mentors during my training. Exceptionally smart, they were an intimidating group of people. But as I walked into the CMR office for the first time, both excited to contribute to the program and nervous that I would not meet the standard they had set, the formers CMRs once again came through. I saw this simple sign posted in the office and was reminded that each of these individuals also had a first day as CMR. They each got through their first teaching session, call schedule conflict, and administrative challenge, and came out as leaders within our program.

Knowing I had the support of those who held the CMR position before me, I got through my first teaching sessions and now have several weeks of CMR behind me. I still have a lot to learn, but I already see an improvement in my teaching and clinical reasoning. I am ready for the new challenges this year will bring, and this simple sign makes me smile every day.

So, to everyone moving on to new roles this July, and facing the insecurity that comes with taking on more responsibility, I echo the statement of the CMRs before me, “Good luck! You will be great!”

July 10th, 2015

Transitions of Care

Andrew Ip, MD

Andrew Ip, MD, is a 2015-16 Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia.

Brief HPI: 3rd year resident, Asian-American male, from Philly, presented to Emory University as a wide-eyed intern July 2012, currently admitted to become a new Chief resident at the VA

Meds: see EMR

Pertinent Labs: see EMR

Top Active Problems:

- Computer Codes – missing but awaiting IT approval

- Awaiting MRI of brain past 48 hrs – syncope work up

- Psychosocial – extremely anxious to start chief-ing and leave behind a transformative experience in residency

Sign-out: NTD overnight

Anticipatory Guidance: If starts to have a panic attack about being chief, ok to give Haldol 2 mg IM

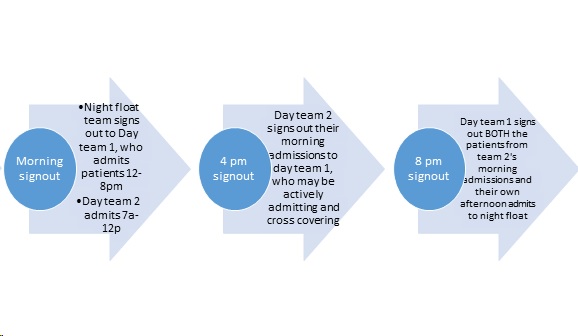

Medical transitions of care are never easy – just the thought of signing out patients to a night float resident frightened me as an intern. Even as an upper-level resident, I was unsure at times of my ability to properly hand off patient care. The above example follows a standardized format to give a cross-cover provider a succinct overview of a patient’s care, but things do get lost in translation. There is no better example of this at my residency program then the ICU month at our public safety-net hospital, Grady. Below is a graphic of our ICU sign-out structure:

Our ICU signout process

This format keeps a team (1 resident, 2 interns) intact by avoiding any 24 hour calls; however it was extremely prone to sign-out mishaps and fragmented patient care. One case I will never forget ended up with a patient coding, likely due to hypoglycemia. During verbal sign-out rounds at 8pm, no one mentioned hypoglycemia; in fact, the call team (day team 1 in above graphic) did not even know much about the patient’s history or reason for ICU admission. The written sign-out also left out the critical information that patient had a blood glucose of ~25 on arrival to the ER. This was the infamous sign-out of a sign-out we all dread from multiple departments, let alone in the MICU.

While medicine transitions of care sometimes leaves a sour taste in my mouth (thankfully, iCompare, the flexible arm, will allow for a MICU 24-hour call system and hopefully address these sign-out issues), I want to now focus on a much different, non-medical transition – leaving residency.

As I signed out in the beginning, I’m going through the initial pangs of transitioning to my new role as a chief resident. It is a wonderful opportunity to teach, mentor, and work on the administrative side of academic medicine. But leaving behind the wonderful class of 52 residents I’ve worked with, laughed with, and cried with has made this transition so bittersweet.

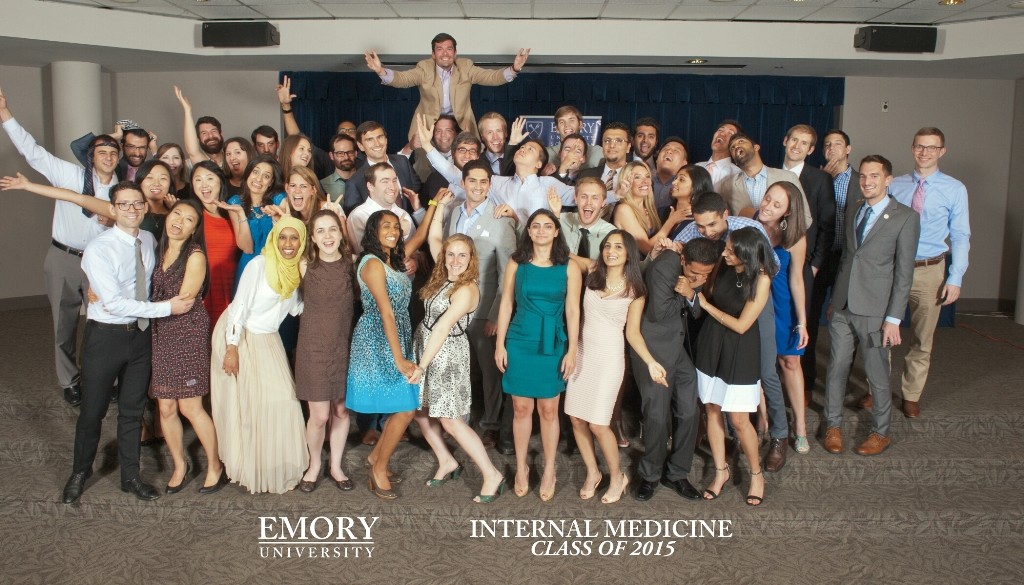

Graduation June 17, 2015 for Emory Internal Medicine residents. Photo taken by Terrance Mason ™

Many in my class will move away from Atlanta, GA — in fact, will move to 13 other states by my count. The time I’ve spent the past 3 years with these individuals has been transformative, a thorough ‘through-the-fire’ refining. Residency launches many of us into a maelstrom of clinical duty mixed with scholarship and rounded out with lifelong bonds formed from shared experiences that only other co-residents can understand. My experience was so intricately tied with who I worked with that I know the friendships and memories made will endure much longer than my career. So if you’re a graduated resident, a graduating resident, or even a budding student doctor, remember to cherish the people you work with and the memories you make along the way.

One part of me is excited to transition to my new role as a chief resident, but the other part of me, ironically, doesn’t want to sign out of residency. Is that so wrong?

I would love to hear other people’s thoughts on transitions in their medical training, or even thoughts on transitions of care within the hospital!

June 30th, 2015

The Storm Is Coming

Ahmad Yousaf, MD

Ahmad Yousaf, MD, is the incoming 2015-16 Ambulatory Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School.

The tempest approaches. July the First. The interns approach the edge of their protected nests and prepare to jump into the whirlwind of senior-hood. The responsibility of managing a team weighs them down like the gravitational force, pulling them toward the unforgiving earth. They will flap their little wings and flex their intellectual muscles frantically in an adrenaline-rushed attempt to gain flight and legitimacy amongst their peers and attendings. If they look below, they will see the monsters they fear awaiting their failure: M&Ms, the furrowed brows of skeptical attendings, families with unrealistic expectations, and chief residents that appear more like administration than compassionate older siblings.As the interns graduate into medical adulthood, the miraculous circle of residency life repeats itself as wide-eyed, innocent, and fragile medical students crack the shells that have kept them from any burden of accountability. They will enter a coddled world of note writing, experiencing their senses and environments, and frequent feeds. Feeds packed full of tidbits of semi-pertinent medical knowledge regurgitated from seemingly reliable sources in the cited portions of UpToDate and Wikipedia. They will learn and grow strong and even feel, at times, that they could do what their predecessors had done without all of the ceremony and ritual. There will be many successes in the coming year, but even more moments of humility. The true question of the day is, do they have the grit and luck to survive the tumultuous time when they are most prone to insult and injury? … And, most of the time, they do.

The final group to speak of during this momentous change of the seasons is the veteran horde of steely-eyed 3rd-year residents. Their faces carry the consequences of 3 years of struggle and perseverance. They are a collection of the wise, the hopeful, and the jaded. They glide through their final days efficiently and competently. Some look forward optimistically with eyes full of dollar bills, whereas others only see the mountains of debt that await them. Both groups, however, have begun the collective sigh of relief that comes with the conclusion of the most grueling, but satisfying, period of life they will ever experience.

And so the day approaches … July the First. The day when some will lift off into the stratosphere and others will be overwhelmed by the gale-force winds. Either way, the chiefs will watch over them, in hopes of catching those who fall and moving out of the way of those who soar. In the meantime, we hunker down … and prepare for the storm that is coming.

June 3rd, 2015

Work-Life Balance for the Uninitiated

Guest Blogger

Jenna Kay, MD, is a Chief Resident at Emory University Hospital. She will be starting her cardiology fellowship in July, 2015.

My daughter was born, 3 months premature, during my third year of residency.  Following a harrowing 3 months in the NICU, we joyfully welcomed her home. After 8 blissful but isolating weeks, I was eager to return to the wards. I happily reunited with colleagues and patients, but I also deeply missed being home. During quieter moments, I daydreamed about stroking my daughter’s tiny fingers and toes, bathing her in the kitchen sink, watching her breathe as she slept on my chest. I wanted to be everywhere at once.

Following a harrowing 3 months in the NICU, we joyfully welcomed her home. After 8 blissful but isolating weeks, I was eager to return to the wards. I happily reunited with colleagues and patients, but I also deeply missed being home. During quieter moments, I daydreamed about stroking my daughter’s tiny fingers and toes, bathing her in the kitchen sink, watching her breathe as she slept on my chest. I wanted to be everywhere at once.

I loved my growing family and was deeply invested in my training, but at the same time, many days felt unbearably hard. I was exhausted. Essentially, I was permanently on call, both at work and at home. There were no days off, no lighter months, no vacation. The support I received from my residency program was incredible, and my husband was an outstanding stay-at-home parent, but I still struggled with the adjustment. Spare time and independence were concepts of the past. A type A perfectionist, I reluctantly delegated tasks like laundry and grocery shopping to my husband, then felt disappointed if he didn’t do things exactly how I wanted. An avid runner, I discovered that I had to get up at 4 AM to feed my daughter, exercise, and get to the hospital by 7 AM. We ate a lot of pasta and canned soup. I finally understood why my older sister with two young children only called me when she was in the car. Multitasking was essential.

I couldn’t be everywhere at once, and I felt guilty leaving my daughter at home. The feeling was partially allayed by my staunch commitment to provide her with breast milk, which was especially important for a preemie. Every 4 hours, I had to excuse myself, find a private room, set up the apparatus, store everything in a specialized ice pack, and clean everything meticulously. Twice during pumping sessions, I had to abruptly detach to run to codes in the MICU. The lactation room was filthy, and I was terrified that I would give my daughter C. difficile. When I felt like giving up, five faculty members offered me their offices to pump. Not a single attending ever rolled their eyes when I asked permission to step out to pump. On the contrary, I felt celebrated and brave. And I kept going. Every time I hit a new low, the pendulum swung, and I soared higher than seemed possible. When my daughter was born, we weren’t certain she would live, and now she was thriving. We felt indescribably blessed.

When I began my year as chief resident, my head was slightly clearer. I was determined to pay it forward. Apart from pointing out lactation rooms (and offering my office) and optimizing schedules, I focused on checking in with new parents. How was life with baby, and how could I support them? We shared stories, advice, photos. Life is a constant juggling act, but somehow it gets easier. It helped to know that we were figuring it out together.

I never questioned my ability to handle both motherhood and medicine. No one told me it was impossible, and I wouldn’t have listened if they did. But a seamless “work-life balance” was impossible. Being in one place always meant I was missing out on the other. Balance is an ever-changing ideal that I set my sights on, but know that I will never permanently reach. It helps me reflect on what I want in the moment and figure out where to spend my energy. I can’t be everywhere, but I can make the most of every situation. My best is more than enough. Repeat.

April 30th, 2015

The Nepal Earthquake: A Harvard Fellow Shares Her Experience Near Everest Base Camp

Guest Blogger

Renee N. Salas, MD, MS, is a fellow in wilderness medicine in the Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Emergency Medicine. She is also an instructor of surgery at Harvard School of Medicine.

Dr. Renee Salas was working in a clinic below Mount Everest Base Camp when a 7.8-magnitude earthquake struck Nepal on April 25, 2015. She shares her perspective as an emergency responder.

Dr. Renee Salas was working in a clinic below Mount Everest Base Camp when a 7.8-magnitude earthquake struck Nepal on April 25, 2015. She shares her perspective as an emergency responder.

It was just after noon, and my colleagues and I were in the living space of the Himalayan Rescue Association (HRA) clinic in Pheriche, Nepal, which is below Everest Base Camp. As realization set in about the events that were occurring, we ran outside to see nearly all of the buildings of the small village of Pheriche crumbling, at least partly. About a third were completely destroyed. In the midst of screams and dust clouds, we quickly circled the village after the earthquake vibrations had settled to see if anyone was injured. Amazingly, the only injury was small — a head laceration. If this disaster had occurred at night, I fear the injury rate would have been much higher. The village came together as everyone comforted one another and assisted those who had completely lost their houses. Some even began rebuilding their stones walls after the initial waves of aftershocks.

Due to the severity of the damage and the strength of the earthquake, we were very concerned that the gravity of the event as a whole was severe. This was my first experience with an earthquake, and the severity of the earth’s movement was astounding. I felt as if I were on a boat at sea. The immediate thoughts and concerns were to the status of the families of the Nepali workers here and to our HRA colleagues in Everest Base Camp and Manang. Unfortunately, we had few means to gain credible information. We had been without internet contact for the preceding few days, and the internet remained inoperable. We attempted to reach Everest Base Camp with the radio system we had in place but were unsuccessful. Through conversations that my Nepali friends had with family and the HRA headquarters in Kathmandu, we learned that the earthquake had affected the city, but we had no understanding of the severity. We then began to assess the damage to the clinic, which had thankfully been limited to only a portion of the living quarters and left the patient treatment area unaffected. The numerous aftershocks we experienced caused the villagers to remain outside for a good portion of the day. Unfortunately, it was snowing with moderate winds, making the situation more difficult.

Due to the severity of the damage and the strength of the earthquake, we were very concerned that the gravity of the event as a whole was severe. This was my first experience with an earthquake, and the severity of the earth’s movement was astounding. I felt as if I were on a boat at sea. The immediate thoughts and concerns were to the status of the families of the Nepali workers here and to our HRA colleagues in Everest Base Camp and Manang. Unfortunately, we had few means to gain credible information. We had been without internet contact for the preceding few days, and the internet remained inoperable. We attempted to reach Everest Base Camp with the radio system we had in place but were unsuccessful. Through conversations that my Nepali friends had with family and the HRA headquarters in Kathmandu, we learned that the earthquake had affected the city, but we had no understanding of the severity. We then began to assess the damage to the clinic, which had thankfully been limited to only a portion of the living quarters and left the patient treatment area unaffected. The numerous aftershocks we experienced caused the villagers to remain outside for a good portion of the day. Unfortunately, it was snowing with moderate winds, making the situation more difficult.

The first patients from Everest Base Camp were two climbing Sherpas who arrived about 9 hours after the earthquake, as they had immediately descended via foot and by horse. We saw and treated them — one was moderately injured and was admitted overnight and one with minor injuries was treated and released. We began to understand the gravity of what had occurred at Everest Base Camp as they recounted their experiences. We initially remained awake, believing that more would be arriving late that evening, but soon retreated to the sunroom (a free-standing building across from the clinic) to sleep given the continued aftershocks.

We awoke the next morning, a little before 6 AM, to the sounds of helicopter traffic heading up the valley. We received word that all of the critically ill and wounded from Everest Base Camp would be evacuated to our facility, and we quickly began preparing for the possibility of significant patient volume. This is exactly the type of mass casualty situation that my emergency medicine and wilderness medicine training prepared me for. Our clinic has two inpatient beds, one consult room bed, and another extra bed in our research room. Our physician staff includes me, Andrew Nyberg from the U.S., and Katie Williams from the U.K. Meg Walmsley from Australia, one of the Everest ER physicians, descended via helicopter that morning to assist with the large patient influx. Gobi Bashyal, our clinic manager, leaped into action and began making phone calls to the surrounding areas and country officials to obtain the necessary manpower and helicopters, while Thaneshwar Bhandari, our assistant manager, began assisting us with preparations. We quickly mobilized the sunroom into a patient facility, and the owner of the Panorama lodge next door, whose lodge was one of just two that had been unaffected by the quake, graciously donated his dining room. We received approximately 10 critically ill patients first and placed them in the clinic and sunroom — many on makeshift beds placed on the floor. There was a mix of Nepalis and international patients. Approximately 20-30 more suffered major injuries and were unable to ambulate. I cared for the most critically ill patients in the clinic and sunroom. In total, we saw and evacuated an estimated 73 patients, including many “walking wounded.” We utilized disaster training and placed large white stickers on patients with their names, injuries, vital signs, and medication administration times. Our resources here include intravenous fluids, medications, and ultrasound. However, we are a remote post without access to blood products or the ability to perform subspecialty procedures that many patients required. Luckily, the weather cleared, and we were able to arrange further evacuation down to the hospital in Lukla, which had more resources. Numerous helicopters, including an MI-17 — which could hold 16-18 patients — made many trips as all patients were evacuated over a 5-hour period.

We awoke the next morning, a little before 6 AM, to the sounds of helicopter traffic heading up the valley. We received word that all of the critically ill and wounded from Everest Base Camp would be evacuated to our facility, and we quickly began preparing for the possibility of significant patient volume. This is exactly the type of mass casualty situation that my emergency medicine and wilderness medicine training prepared me for. Our clinic has two inpatient beds, one consult room bed, and another extra bed in our research room. Our physician staff includes me, Andrew Nyberg from the U.S., and Katie Williams from the U.K. Meg Walmsley from Australia, one of the Everest ER physicians, descended via helicopter that morning to assist with the large patient influx. Gobi Bashyal, our clinic manager, leaped into action and began making phone calls to the surrounding areas and country officials to obtain the necessary manpower and helicopters, while Thaneshwar Bhandari, our assistant manager, began assisting us with preparations. We quickly mobilized the sunroom into a patient facility, and the owner of the Panorama lodge next door, whose lodge was one of just two that had been unaffected by the quake, graciously donated his dining room. We received approximately 10 critically ill patients first and placed them in the clinic and sunroom — many on makeshift beds placed on the floor. There was a mix of Nepalis and international patients. Approximately 20-30 more suffered major injuries and were unable to ambulate. I cared for the most critically ill patients in the clinic and sunroom. In total, we saw and evacuated an estimated 73 patients, including many “walking wounded.” We utilized disaster training and placed large white stickers on patients with their names, injuries, vital signs, and medication administration times. Our resources here include intravenous fluids, medications, and ultrasound. However, we are a remote post without access to blood products or the ability to perform subspecialty procedures that many patients required. Luckily, the weather cleared, and we were able to arrange further evacuation down to the hospital in Lukla, which had more resources. Numerous helicopters, including an MI-17 — which could hold 16-18 patients — made many trips as all patients were evacuated over a 5-hour period.

The local and international community here in the region came together in a way unlike anything I have ever experienced. Locals from the village and neighboring town of Dingboche assisted with transporting patients, arranging supplies, and giving patients and volunteers tea and food. International trekkers with nonmedical backgrounds who were in the region assisted selflessly with patient transport and donated first aid supplies and materials. We had numerous international physicians, nurses, and EMTs who spontaneously arrived and quickly set to work seeing patients, checking vital signs, and administering medications. When the last patient was evacuated, the nearly 100-200 people who had assisted all cheered and hugged one another for the amazing team effort… and then dispersed back to their villages while many international trekkers continued their descent to lower villages.

The local and international community here in the region came together in a way unlike anything I have ever experienced. Locals from the village and neighboring town of Dingboche assisted with transporting patients, arranging supplies, and giving patients and volunteers tea and food. International trekkers with nonmedical backgrounds who were in the region assisted selflessly with patient transport and donated first aid supplies and materials. We had numerous international physicians, nurses, and EMTs who spontaneously arrived and quickly set to work seeing patients, checking vital signs, and administering medications. When the last patient was evacuated, the nearly 100-200 people who had assisted all cheered and hugged one another for the amazing team effort… and then dispersed back to their villages while many international trekkers continued their descent to lower villages.

We have remained opened and will continue to see locals and trekkers until our job here is done. This likely won’t be until Everest Base Camp is cleared, and then we will convene with our Everest ER friends and colleagues and determine the next best course of action. Those descending from Everest Base Camp have shared their stories about their experiences on that fateful day, and we’ve tried to assist individuals as they attempt to learn about friends and loved ones. It has still been a very surreal situation that hasn’t truly hit home yet. There have been continued aftershocks that have served as jarring reminders that the danger is ongoing. Helicopter traffic has been constant between Everest Base Camp and Pheriche as climbers from Camps I/II and Everest Base Camp — and the bodies of the deceased — are evacuated.

Until we regained access to the internet yesterday evening, we had been in a vacuum with limited knowledge of the gravity of the situation within the remainder of this amazing country that has become our home for the past 2 months. This is a country full of loving people, and the innately welcoming culture has created a collaborative and selfless post-disaster environment here in the Khumbu Valley. However, this is a country with very limited resources. We spent the first week of March in Kathmandu for orientation before our acclimatization trek here, so I know parts of the city well. The situation in Kathmandu sounds grave as medical facilities have been quickly overwhelmed and they have struggled to take care of patients in damaged buildings and in the continued wake of aftershocks. The situation in the more remote outlying villages is unknown. As food and water resources dwindle and the lack of sanitation grows, risk for epidemics is high — which will turn an already dire situation into a nightmare. The country will require basic needs such as food/water and medical and infrastructure personnel and supplies. Any assistance, depending on your resources and abilities, would be greatly appreciated, including prayers. Similar to the Haiti earthquake aftermath, in which I participated, this will be a marathon and not a sprint as further pitfalls lie ahead as we attempt to rebuild this country. As I have limited knowledge of the true situation in Kathmandu, I cannot speak to specific needs currently, but these will become clear as time progresses and especially when I descend to the city in the coming 1 to 2 weeks.

April 10th, 2015

Being Taught to Be a Teacher

Guest Blogger

Guest Blogger: Jenna Kay, MD, is a Chief Resident at Emory University Hospital. She will be starting her cardiology fellowship in July, 2015.

How to insert a central line had been drilled into me long before my first attempt, and I was admittedly nervous performing my first procedure as an intern. But, as a senior resident, watching the intern in front of me insert his needle into the patient’s neck was 10 times more anxiety-provoking. I wanted to guide him successfully through the first of many procedures he would need to master, in the same way my senior resident had guided me. I fought a strong temptation to take over entirely. By now, I could do a central line in my sleep. But teach one? I hadn’t given it much thought until that moment.

Medical trainees are provided an extraordinary amount of resources geared toward helping us learn. Beyond experiential learning, we have journals, meetings, webinars, textbooks, virtual interactive cases — just about any imaginable resource for every kind of learner. The opportunities to learn how to teach, however, are a smaller portion of the curriculum and a relatively new area of focus for medical institutions. Before I stood behind my intern that day, I was entirely focused on my own learning. But in that instant, my emphasis shifted: Did I have the necessary skill set to teach? As an aspiring academic clinician, I was hungry for those resources.

In the final month of my intern year, we attended a session with experienced faculty who advised us on effectively leading a team, engaging trainees at different levels, and giving constructive feedback. It all rang true, based on my experience as a learner, but I still felt hesitant to jump in. Teaching seemed to be an immense responsibility that humbled me before I even started.

On my first day as a chief resident, I sat at a pristine desk with a full candy jar and plenty of tissues, but… lead morning report? Me? I was excited by the theoretical possibility of becoming a better teacher but also full of self-doubt and reluctant to ask for help. Did I really want to ask someone to watch me lead a noon conference, or teach aspects of the physical exam that I myself had mastered only incompletely? The answer was no — I did not want to subject myself to scrutiny and judgment in front of an evaluator. But the answer was also an overwhelming yes, because I could see how much potential for growth lay ahead if I could push past my ego.

As part of our faculty development program, I signed up for a teaching mentor. He was full of ideas. We agreed that he would sit in on conference and watch me lead rounds; I made plans to shadow him with his team. I started to recognize and accept other opportunities to teach that I had assumed were only for “real” teachers, and I made a point to ask for feedback, painful as it sometimes was. Hands down, the hardest part was making the decision to ask. Once I took the plunge, I always gained perspective and felt inspired about what to try next.

Now my eyes are wide open, and experience has opened the door to bravery. I’ve been able to take advantage of many teaching opportunities and have started to create a personalized teaching blueprint. When residents come to my office asking for advice on teaching, guiding them is one of the highlights of my job.

Jenna Kay, MD