November 20th, 2015

Crossover

Raktim Ghosh, MD

Raktim Ghosh, MD, is a 2015-16 Chief Resident at St. Vincent Charity Medical Center, in Cleveland, Ohio.

My final year of residency is almost halfway complete. The job market for 2016 is heating up. For last month, I have been starting my day by browsing job websites and checking emails from the recruiters. After completing two residencies in two different specialties and one research fellowship, I want to get an academic hospital medicine position, but choosing the first job is no less intense than choosing the right residency or fellowship program. The challenge starts with creating a comprehensive CV, which summarizes all my achievements, including education, training, research, and administrative experiences. Undoubtedly, my chief residency experience fills up some paragraphs in the CV, including teaching, leadership, and administrative roles. The next step is getting good letters of recommendation from the program director and other senior faculty as required by some academic institutions.

Making my career decision of academic vs. community or private practice is not easy at this juncture of my professional life. This is not just choosing between academia vs. more money. Part of it could be that I am not very familiar with job roles outside of academia. Deciding whether to stay at my alma mater vs. moving to a new system or facility is difficult as well.

Job interviews are different in many ways from residency and fellowship interviews. It’s not just about all-expense paid trips, staying in nice hotels, and chauffeur-driven cars. The question I have been asked so far in every job interview is, what can I contribute besides clinical medicine? The next 2 years as a junior faculty member will be a crucial foundation step for my long-term goal of excelling in academic medicine. This will be the time to not only boost everyone’s (including my own) confidence in my ability but make myself prominent in the department. Outside of clinical work, I also need to focus on an area of interest, which could administration, medical education, or clinical research.

Job interviews are different in many ways from residency and fellowship interviews. It’s not just about all-expense paid trips, staying in nice hotels, and chauffeur-driven cars. The question I have been asked so far in every job interview is, what can I contribute besides clinical medicine? The next 2 years as a junior faculty member will be a crucial foundation step for my long-term goal of excelling in academic medicine. This will be the time to not only boost everyone’s (including my own) confidence in my ability but make myself prominent in the department. Outside of clinical work, I also need to focus on an area of interest, which could administration, medical education, or clinical research.

I was never good at reading legal documents, but this is time to read in between the lines in the contract paper. Starting with compensation, number of shifts, protected time, malpractice, tail coverage RVU, and productivity bonuses to name a few.

I want to become a physician researcher, so it’s imperative for me to choose a senior faculty member as my mentor whose interests match mine.

Very excited and maybe a little nervous… I am ready to take the plunge in the real world after years of training.

Wish me luck.

November 13th, 2015

Procedural Competency

Briana Buckner, MD

Briana Buckner, MD, is a 2015-16 Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

It’s 2 am, and the patient’s blood pressure is beginning to rapidly decrease. Every IV line is occupied by an antibiotic or IV fluids, and we are in need of a vasoactive medication. The nurse comes to my computer and sternly states, “We can no longer avoid it. I think the patient needs a central line.” I quickly say “OK,” but I don’t move. I am momentarily frozen by my unease with the bedside procedure ahead. My mind is racing and questioning whether I can make any other treatment or management decision to avoid this procedure. I’ve got nothing. This is definitely what the patient needs. The nurse asks, “Are you signed off?”

I reply earnestly, with a strong “yes,” to convey to her that I am confident in my skills and comfortable. The honest reality is that I am nervous about doing this central line procedure and am finally facing my procedural comfort level straight on. Although I met the institutional requirement for quantity of this procedure needed for unsupervised performance of this skill, my comfort had waned in the few months since I had performed the procedure.

The real question I faced that night as a second-year resident was whether my level of comfort reflected my competency and ability to complete the procedure safely. If we assume that comfort reflects competency, our current quantitative benchmarks for performing unsupervised procedures may not be enough. In one prospective study of residents’ comfort with 9 aspects of 4 common bedside procedures, the residents reported lack of comfort in at least one aspect of 51% of procedures performed over the course of a year (1). Higher procedure numbers and direct supervision were associated with greater comfort.

What feels like a recent development of more physicians being less comfortable with bedside procedures may really be a result of procedures transitioning primarily into the hands of specialists. A survey of internists from the American College of Physicians showed that primary internists regularly performed 16 in-office procedures in 1986, versus 7 in 2004 (2). There has also been a recent movement to provide procedure-service models on many inpatient services that serve as exemplary models of procedure execution. These models offer expert supervisors, consistent teaching technique, and a controlled environment for the patient. Although these models are a plus for the patient, some would argue procedure services are performing procedures that previously would have been performed by trainees — the same trainees who must develop into our next generation of experts.

So how do these issues affect our journey to procedural safety for our patients and the training of future procedural experts? In recent years, the American Board of Internal Medicine has transitioned away from quantitative requirements to determine if physicians-in-training are ready for unsupervised performance of skills and has implemented milestone-based assessments. These milestone- and competency-based assessment tools require trainees to demonstrate effective mastery of needed technical skills and to understand and be able to manage complications (in addition to reaching a defined number of each procedure). Although the ABIM has embraced milestone-based evaluation, many of our training programs continue the longstanding “signed off” culture after 5 or so of a common procedure are performed. Which, in my case, was not the point of comfort and may have not been the point of competency. As procedural training often is considered one of the most important aspects of training, I hope with innovation and diligence we can continue to train competent procedural experts.

Do you have thoughts on bedside procedural comfort or competency? How can we improve procedural training? Please feel free to share your comments.

References:

- Huang GC et al. Beyond the comfort zone: Residents assess their comfort performing inpatient medical procedures. Am J Med 2006 Jan; 119:71.e17.

- Wigton RS and Alguire P. American College of Physicians. The declining number and variety of procedures done by general internists: A resurvey of members of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2007 Mar 6; 146:355.

October 23rd, 2015

Musings from Japan

Gregory Shumer, MD

Greg Shumer, MD, is a third-year resident and 2015-16 Co-Chief Resident at the University of Michigan Family Medicine Residency Program in Ann Arbor.

I spent the first two weeks of October in rural Shizuoka, Japan, rotating through clinics and hospitals in Mori-machi and Kikugawa, and observing medical education at Hamamatsu Medical School. The University of Michigan Department of Family Medicine has a unique and positive relationship with the Shizuoka Family Medicine residency program that allows for collaboration. I lived in Japan for 1 year before medical school, and I was thrilled to be accepted to the international rotation in Shizuoka. Below are some of the most striking observations from my time in rural Japan.

During an afternoon clinic session with Dr. Yamada at Mori-machi clinic, I observed a stretch when she saw patients aged 83, 77, 86, 91, and 96 — consecutively. The two patients older than 90 were both women who lived independently, and who were able to walk to clinic unassisted for their appointments.

The proportion of the Japanese population older than 65 is projected to increase from 12% to 40% between 1990 and 2050, and was estimated at 22.7% in 2009. In comparison, the U.S. elder population is projected to increase from 12% to 21% over that same time, and was estimated at 13% in 2009 (1, 2). The two major variables that are driving Japan’s rapid demographic shift are the incredibly long life expectancy (86.1 for women, 79.3 for men), and the relatively low birth rate (1.41 births per woman) (1).

Healthcare financing in Japan — Containing costs

Japan’s health financing structure is very different from the U.S. system. Japan has achieved universal health insurance through a combination of employment-based and government-financed insurance. The Japanese government keeps healthcare costs low through setting a strict national fee schedule on all services and procedures, which results in lower payments to physicians and hospitals than in the U.S. The fee schedule sets the price, and doctors are then paid fee-for-service (1). Prices for services that increase in volume over time tend to be lowered to control cost. For example, the price for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head was recently reduced by 30% to 11,400 yen (US$104) (3). Because of efforts like these, Japan spent just US$2878 per capita on healthcare in 2009 (8.5% GDP), compared with the US which spent US$7,960 per capita on healthcare in 2009 (17.4% GDP) (2).

Universal coverage in Japan improves access and eases transitions of care

One afternoon, I accompanied Dr. Tsunawaki on a home visit to see a 90-year-old woman with advanced stomach cancer, who had been discharged from the hospital 1 week prior with a plan for home healthcare services with focus on comfort care. I asked him about the process of discharging a patient with home services or to a long-term care facility. I voiced my frustration about difficulties I often encounter when trying to find placement for patients who are uninsured or underinsured in the U.S., which can delay discharge. He explained that because of the universal healthcare system in Japan, the process of discharging any patient home with home services, or to a long-term care facility, is a relatively simple and efficient process.

Brief comparisons: U.S. vs. Japanese healthcare systems

Although several aspects of the Japanese healthcare system work well, the strict national fee schedule isn’t perfect. As a result of low reimbursements, physicians must see a high volume of patients per day, squeezed into shorter visit times, which can disrupt the physician-patient relationship. Although the Japanese system provides less benefits for physicians, there is no shortage of well-qualified doctors, and it keeps costs low and access high for consumers, making it a successful system, in my opinion.

The U.S. spends the most money in the world on healthcare with variable results on quality metrics compared with other countries (2). The Affordable Care Act (ACA) helps by decreasing the number of uninsured patients through the Medicaid expansion and other measures, and by creating measures to increase access and (potentially) lower costs. However, it fails to provide universal coverage, and how the ACA will affect spending in the near future is unclear (4). Because of this, the U.S. would be wise to continue learning from healthcare systems with universal coverage that have been successfully implemented, like those in Japan and other industrialized nations.

Opioids are rarely prescribed in Japan

While I was working with Dr. Horie one morning at Morimachi clinic, we saw a 66-year-old man with chronic low back pain that had acutely worsened. Dr. Horie refilled his prescriptions for Tylenol and topical menthol-based pain-relief pads, and provided some stretching and strengthening exercises for his low back.

Outside of the patient’s room, I asked Dr. Horie about how often opioids are prescribed to patients in Japan.

“Almost never,” he told me. “Really, only for terminal patients to help with their pain.”

“What about postoperatively? Or for acute pain relief after injuries?” I questioned.

“No, we primarily use NSAIDs, Tylenol, and pain relief pads.” He explained matter-of-factly.

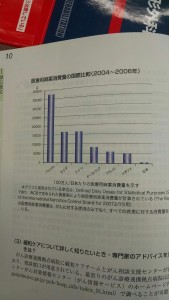

He then showed me a chart (pictured left) that visually displayed how the U.S. and Japan are on opposite ends of the spectrum in terms of opioid prescribing habits: The U.S. prescription rate is represented by the bar on the far left of the graph, and Japan’s rate is the barely visible bar on the far right. In comparison to Japan’s strikingly low use of opioids, the epidemic of opioid drug abuse and misuse in the U.S. is well-documented: An estimated 259 million prescriptions were written for opioids in 2012 — enough for every American adult to have a bottle — and every day an estimated 46 people die from prescription medication overdoses (6).

I saw several patients with complaints of acute and chronic pain while working in clinics and hospitals in Japan, but the only time I saw opioids used was for terminally-ill patients with cancer-related pain during home visits.

Finally, Japan is beautiful

If you are searching for a spot to spend your next vacation or work-related adventure, I highly recommend the rolling green hills of the Japanese countryside. The natural beauty of the countryside is matched by the warmth and hospitality of the people. Thank you to everyone at Shizuoka Family Medicine for making me feel at home during my 2 weeks there; I hope to see you again soon.

Special thanks to Dr. Machiko Inoue, the program director at Shizuoka Family Medicine, for helping to coordinate my experience in Shizuoka, and also to Professor Jersey Liang, for the education he has provided through his Health Systems course at the University of Michigan Executive Master’s Program in Health Management and Policy, which helped provide some of the material for this post.

References:

1. Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K. Understanding Health Policy, Chapter 14. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2009.

2. Squires, David A. Explaining High Health Care Spending in the United States: An International Comparison of Supply, Utilization, Prices, and Quality. Issues in International Health Policy. The Commonwealth Fund. 2012; 1.

3. Ikegami N, Campbell J. Japan’s Health Care System: Containing Costs And Attempting Reform. Health Affairs. 2004; 23:26.

4. Connors E. Health Care Reform—A Historic Moment in US Social Policy. JAMA. 2010; 303:2521.

5. Cancer Palliative Care Guidebook. Nihon Ishikai. 2013. pg 10.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Vital Signs – Opioid Painkiller Prescribing. 2014. (http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/opioid-prescribing/)

October 9th, 2015

We Were a Wreck, but the Baby Was Fine

Ahmad Yousaf, MD

Ahmad Yousaf, MD, is the 2015-16 Ambulatory Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School.

I dropped the little booger off at daycare today. I was over-prepared, and the nanny’s face said it all, “this is your first time, huh?”

It was. Before this, Safiya was being taken care of by her loving grandmothers and a wonderful nanny that was literally like family. But now she is almost 2, the nanny had moved on to greener pastures, and grandmothers have jobs and other things going on in their lives. I know this post has started off like a mommy/daddy blog, but this is different from the cliché “First day of Daycare” sob story (or, I like to think it is, at least). This is how I felt today:

http://https://youtu.be/JghkG4WydNk

We have a story:

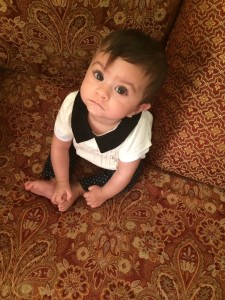

Safiya was born at 3:39 PM on 11/8/13, even though she was due 8 weeks later. She was an SGA neonate born to a mom suffering from pre-eclampsia whose blood pressure was twice the normal range. After 2 days of labor and 2 days of steroids, she came into the world with a little squeak that literally almost made me fall to the ground as I understood what that little mouse noise meant. I imagined that, at that very moment, her blood circulation reversed as her lungs went from unwelcoming high pressure to loving and kind low pressure. Blood rushed into her pulmonary vasculature, and, as she took another deep breath between squeaks, oxygen diffused across tiny, wet alveoli and was delivered to her 3.5 lb body. As the NICU team worked on her, I looked over their shoulder at the acrocyanotic newborn and instantly fell in love. My wife gradually recovered, I was a wreck, but the baby was fine.

She spent the next 28 days in the neonatal ICU surrounded by the beeping of her telemetry monitor that alerted the doctors that she was apneic for short periods of time… Those moments of breathlessness left her mommy and me in a state difficult to describe: Imagine floating alone in a pool in the dark of night and, when you come up for a breath, you hit a glass ceiling. Your body begins to panic as it starves for oxygen, and you slam on the glass as the blackness envelopes you. You hear the beep. You see the number on the monitor go from 60 to 30 and then to 0, and you punch harder. The nurse runs over and stimulates the tiny being from behind the NICU incubator, and she awakens. And just as she takes that deep breath, you break through glass, get your head above water and gasp with her. That happened for 28 days… every day. We were a wreck, but the baby was fine.

We took her home on a cold, rainy day at a fighting weight of 5 pounds on an apnea monitor and caffeine. She felt like a feather in my palm, and her gray eyes stared at me like I meant something. I would place her chest to my ear and hear the harsh sound of blood rushing through the hole in her ventricular septum during systole. Every time, I was relieved that it was beating. Relieved that she was breathing EVERY TIME. Being a physician didn’t help. Being a pediatrician who had just spent his final senior month in the NICU didn’t help. As a matter of fact, it made it worse. I dreamt of intraventricular hemorrhages, pulmonary hypertension, and cerebral palsy. I tested for spasticity as she weakly sucked on a bottle, and I would wake up in the middle of the night to reach over to her bassinet and make sure I could feel her chest rise. When she arched her back from reflux, my heart arched with her. When she turned red from infant dyschezia, I would find myself unable to swallow. When her arms jerked in her sleep from benign neonatal myoclonus, all I could think about was getting an EEG. When she slept through a meal or had two consecutive spit-ups, I wanted a blood gas and an ammonia level because I was sure it was a urea cycle defect. My wife and I were a wreck, but the baby was fine.

All this while, my wife and I were in the throes of residency. My wife commuted to the city and sat in hours of traffic on the cursed Cross Bronx Expressway while covertly pumping breast milk that provided immunity for her little bundle of joy and anxiety (yes, she pumped while driving). I would run a code at work and give a family bad news and then rush home to have Safiya sleep on my chest while I read about inflammatory bowel disease and the side effects of a variety of HIV meds. I would come back from night call exhausted but exhilarated to hold her and sleep with her close enough to me that I could feel her breath on my face. We were drowning in our everyday lives, but it kept us from drowning in our worry. We were a wreck, but the baby was fine.

Here we are today: A day when I entrust her to a group of strangers surrounded by more adorable little strangers that may bite or kick or even kiss her… I dropped all the hundred or so little containers of random foods that my wife had packed into her little cubby and moved towards the door as she was distracted by a coloring book. She cried a little when she caught me sneaking away, and I took that as an excuse to run back to her. I picked up her now 30 lb frame and gave her a hug and told her I was right down the street. She looked at me in the eye through angry tears and clearly did not approve. A few seconds later, I ran out of the room when she was again distracted by the clock in the room. I watched her through the daycare window for a while as she played with her new friends and toys. I took a picture… or 7… and sent them to my nervous wife in the Bronx. We were a wreck, but the baby was fine.

Alhamdulilah.

~Yousaf

September 25th, 2015

More Work Hours, More Strokes?

Andrew Ip, MD

Andrew Ip, MD, is a 2015-16 Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia.

Do doctors work too much? Residents would probably say “Yes! I’m burnt out,” and supplement it with some form of “I’d much rather work less.” Outside of residency, the answer may be a mix of yes, no, and maybe.

Recently, Lancet published a meta-analysis on work hours and its effect on incident coronary disease and stroke. The study showed that those who worked more than 55 hours weekly on average had an increased relative risk of 33% for stroke and 13% for coronary disease. Stroke risk increased linearly as average work hours rose. NEJM Journal Watch’s Dr. Bruce Soloway reviewed this article; his comment is below:

“Mechanisms for an association between long working hours and incident CHD and stroke are unknown but might include prolonged or repetitive stress, physical inactivity, and excess alcohol consumption. Average working hours vary widely among developed countries and represent modifiable social decisions. Social policies encouraging or requiring people to work longer hours could have substantial health implications.”

“Mechanisms for an association between long working hours and incident CHD and stroke are unknown but might include prolonged or repetitive stress, physical inactivity, and excess alcohol consumption. Average working hours vary widely among developed countries and represent modifiable social decisions. Social policies encouraging or requiring people to work longer hours could have substantial health implications.”

These results must sit in the consciousness of nearly all residents, regardless of specialty, as our average work hours usually are greater than 50 and often average greater than 60 or 70 hours on a busy inpatient month. At our residency program, we realize a personal work/life balance is key, given our rigorous clinical demands. Wellness initiatives at Emory this year include more happy hours, a research mentorship program, Fitbit competitions, and food at conferences. Even as residents graduate, attending/fellowship life does not get any less stressful, although work hours usually are fewer. But how do we prevent burn out? After all, we are a primarily service-oriented occupation that often requires selfless sacrifice in the name of greater good for patients’ well-being.

One solution might be a Stanford ER program that relies on the concept of ‘time-banking’ to save physicians from burning out (Washington Post article). This $250,000 2-year pilot rewarded ER attendings who spent extra time at work mentoring residents, covering shifts for colleagues, or spending time on committees. The extra ‘banked’ time resulted in benefits such as grant-writing help, dry cleaning pick-up, or even food deliveries to home. The result was astonishing, as most physicians improved their work-life balance and job satisfaction and, importantly, wrote more grant proposals (22 were submitted, with an above average 40% success rate for a whopping $10 million in support). The latter alone is a compelling reason to fund these types of time-bank pilots elsewhere, as they can very quickly pay for themselves. A second reason is that the culture within this emergency department became more collegial and friendly — many attendings volunteered to cover coworkers’ shifts as they realized their service would not go unappreciated because of the time-bank system.

This innovative method to avoid burn-out and improve work-life balance may be a way to address the stress that can contribute to excess strokes, especially because work hours will not go below 55 anytime soon for residents or attendings. Physician-wellness curriculums are also key to teach physicians how to cope with stress or manage their time effectively. My own personal tip to is to not lose whatever defines you as you go through medical training — for me this included playing basketball or Frisbee, talking to loved ones, and attending church whenever possible.

I would love to hear any other social-wellness initiatives that were successful for you personally or within your residency!

-Andrew

September 16th, 2015

Tips for Intern Survival

Ahmad Yousaf, MD

Ahmad Yousaf, MD, is the 2015-16 Ambulatory Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School.

With the start of the residency year comes a new batch of excited residents who will have many of the same successes and failures as those who tread the path before them. They will quickly fall into cliché niches within the residency class: the gunner, the humanitarian, the slacker, the superstar, the researcher.

Their medically immature hands will explore their new environments the way my 2-year-old discovers that things that are hot will burn her and that sand is icky but shapeable and that every action has consequences. The new interns will learn that what comes out of their mouths can be the shovel that buries them with the scrubs of residency or the rocket that elevates them into the ranks of legendary residents before them. A few will reveal themselves as superstars, and a few unfortunates will come out on the dreaded bottom. The reality is that most residents are average, and average doctors are great!

So what are 8 (semi-serious) categories of residents that you do not want to become? If you are labeled as one of the following, your residency experience will be a bit rougher than it needs to be. And, then, 7 things that will help you be above average!

- Lazy/Apathetic: This is the category of death for an Internal Medicine intern. If you gain the reputation as the doc who does everything he or she can do to NOT do anything, you will have a hard time. Word travels through residency programs like poison gas. You may not know it is around but, by the time you realize you have been exposed, it’s too late to recover from the fumes. NEVER be the lazy one.

- Debbie Downer: Every resident complains. You should; it is natural to complain about the absurd torture that is residency: sleepless nights, stressful days, and immeasurable workloads, mixed in with the gumbo of constantly coming face to face with mortality and suffering. In fact, it would probably be strange if you did not commiserate with your colleagues after a long day of work. Debbie Downer, however, takes it to another level. Nobody wants to work with someone who never has anything positive to say. At the first chance for a break in the hectic day on the wards, the last thing a team of residents want to hear is one of their own constantly reminding them how bad they have it. You have to bite your tongue once in a while and try to find a silver lining, even if that silver lining is simply being able to go home at the end of the day.

- Always Late Guy/Gal: This is self-explanatory. If you want to get extra negative marks, walk in 10 to 15 minutes late with a cup of coffee, a perfectly crisp white coat, a big awkward smile on your unpunctual face, and muffin crumbs in your beard. Everybody wants to get home to their family, food, and bed… Don’t mess with that.

- Arrogantly Ignorant: In traditional Islamic scholarship there is this concept of simple vs. compounded ignorance. A teacher’s goal is to move people from compounded ignorance to simple ignorance and with that achievement, the teacher can claim that he or she did his or her job. The major ingredient that differentiates failure from success is the presence or absence of a dose of humility. Examples of each:

- Simple Ignorance — this is OK!

- Question: What is behind that wall?

- Answer: I do not know.

- This is a completely acceptable answer. In fact, we know you do not know! That is why you are here, to learn. Take it a step further and follow that up with, “I will go look it up,” and all of a sudden you look like a go-getter superstar!

- Compounded Ignorance — NOT OK!

- Question: What is behind that wall?

- Answer: There is a lion behind that wall… ?!?!

- The problem is this: You do not know what is actually behind the wall, because you do not yet have the tools to see over or behind it. You have confidently (and likely overconfidently) answered a question about which you had no clue. This is frustrating for team members and, more importantly, dangerous for your patients.

- Simple Ignorance — this is OK!

- Missing the Forest for the Trees: BUN went from 11 to 12, MCHC is at the lower limit of normal, and the patient’s left toe nail is a little green… The problem? The patient is hypotensive and crashing, and you have wasted 10 minutes telling me that he has a pet dog with a family history of anxiety, and you forgot to mention the meningeal signs you elicited on exam. Sometimes you have to take a step back, take a deep breath and reassess. Asking your seniors will also help big time.

- Jaded on the First Day of Residency: You have no reason to be jaded on your first day of residency. If, by the end of your first week, you come into work with beard stubble, a stained white coat, a litany of derogatory things to say about ‘all of the drug-addicted low-lifes’ for whom you provided care, and you sigh every time you get an admission, you may need to check yourself. You should be coming up with wide differentials with zebras at the bottom and not just be assuming that your poor patient is ‘just another drug-seeker.’

- The Rambler: Say what needs to be said and nothing more. Present objective facts and not how you feel about every ‘normal’ or ‘abnormal’ finding. You are an intern, and your job is to collect and disseminate information while learning during the process. One of the most painful things to see is a resident who does not know when to say nothing… Do less talking and more nodding and listening, and you will be golden.

- Improper Hygiene: How expensive your clothes are does not matter… whether they are clean and ironed does matter. I am a proud member of the Marshall’s and Kmart clubs, and they have worked out just fine for me. Hygiene includes smelling ‘neutral.’ No heavy cologne or Axe spray required… you are getting very up close and personal with many people, and their nostrils will appreciate not smelling you (good or bad).

So far, I have given you insight on what to avoid. Here are some things you can do to rise to the top and survive that first year of residency:

- Come to work on time, and be grateful for the opportunity to treat people and to make a phenomenal living while doing so.

- Keep your head down, and get the work assigned to you done before you go home. You would be surprised how just doing exactly what you are instructed to do in the expected time translates into people knowing that you are ‘one of the good ones.’

- Recognize that perception is everything. This may often seem (or be) unfair, but no matter how smart, efficient, and compassionate you are, if you have an image problem or a bad reputation, it is very hard to shake.

- Be optimistic! You are in a field many would love to be in. You get to be closely involved with people who are at the most vulnerable moments of their lives; accept the responsibility, and own it.

- Know your strengths and weaknesses. If punctuality is a weakness for you, plan to get to work 15 minutes earlier than you have to. Not being punctual can really ruin the reputation of an otherwise solid resident. If you’re bad at documentation, spend extra time on it. (If you’re good at it, help your colleagues!)

- Remember that nobody in the room knows everything and that nobody expects you to know everything either. Be willing to be humble and say you do not know. Use this as a motivation to go find the answer in a book or through a senior/attending.

- Usually interns have the most book/basic science knowledge on their team, but the least clinical sense. This is expected, because the only way you pick up the latter is with sheer volume and exposure. You need to see everything many times before your Doctory Spidey Sense becomes reliable. Give yourself a break and be willing to make controlled mistakes so that you can learn what really matters.

That’s it! You got this! Keep your head up, caffeinate often, and ask your seniors/chiefs for help. You are going to be great!

~Yousaf

September 11th, 2015

Overnight Admission

Gregory Shumer, MD

Greg Shumer, MD, is a third-year resident and 2015-16 Co-Chief Resident at the University of Michigan Family Medicine Residency Program in Ann Arbor.

BEEEP BEEEP BEEEP BEEEP – I pressed a button to silence my pager and rose groggily from the bed in the on-call room. I hadn’t truly been asleep, just catching a quick rest between pages. It was 2am. I was 19 hours into my shift and, from the looks of the page, there was a new patient ready for admission to our family medicine inpatient service. I picked up the phone and called down to the ER to get the full story.

“New admission: 47-year-old male who’s dehydrated and needs IV fluids and pain control before upcoming flight to his home in east Africa. He’s got widespread metastatic cancer; oncology thinks days-to-weeks to live, without additional options for treatment. Enrolled in hospice last week but hasn’t seen them yet. He bought plane tickets for him and his sister, and his plan is to fly home in 2 days to be with his wife and child for the remainder of his life.”

The ER physician’s words echoed in my head as I reviewed the patient’s chart. This was not the typical admission to our service. I slipped on my white coat and began the long walk from the 8th floor of the hospital down to the basement — the home of the emergency department. As the senior night resident, it was my job to admit this man to the hospital.

As I approached his room, I remembered a lesson from one of the palliative care specialists in our department. He taught that, at the end of life, it’s most important to first determine the patient’s goals and then let those goals guide recommendations and therapy. For critically ill patients, we have IV fluids and medications to support dropping blood pressures, oxygen and mechanical ventilation to help with breathing, and strong antibiotics to stave off disease. However, if the patient’s goals are to be comfortable and at home, surrounded by loved ones at the end of life, then these invasive and often-times uncomfortable medical interventions are better left on the sideline, replaced by medications to help make the patient more comfortable.

I knocked on his door, waited for permission, and entered. Inside the dimly lit room were two people: A middle-aged woman adorned in a beautiful light-blue hijab stood and introduced herself as the man’s sister; and the patient, bald and with sagging eyes, laid on the hospital bed looking up at me. I introduced myself to both of them, glanced at the monitor, saw with relief that his vital signs were within the normal ranges, and then sat in a chair next to his bed. He sat up and extended both of his hands towards me, enfolding my right hand in a warm and gentle handshake. He smiled and told me his name. Despite these signs of strength, he looked cachexic and weak.

“What are your goals for this hospitalization?” I began.

“I know I do not have long in this world, and I am at peace with this,” he began. “I want to go to my home country to be with my family for my remaining days, but am worried because I have not been able to eat or drink.”

BEEEP BEE… I pressed the button to silence my pager and urged him to carry on. Whatever it was, it could wait.

“I would like to get fluids to regain my strength,” he continued, “and medication to help with pain and nausea so I can endure the flight to my home.”

I nodded in understanding. I reviewed his medications and discussed what had worked best for his symptoms in the past. I assured him and his sister that our objectives as his doctors would be in line with his goals, and we would aim to get him safely on his flight in 36 hours.

At the end of our conversation, he smiled at me. “Thank you for your humanity,” he said.

©www.tOrange.us Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

I never saw him again. I ordered IV fluids, and medications for his pain and nausea. I gave sign-out to the morning team to let them know his goals and, when I followed up with the team later that week, was happy to hear that his symptoms had improved and he was able to get the appropriate prescriptions in time to make his flight.

I played a very small part in his care, but the brief interaction still sticks with me. And, I hope that by doing my part as the overnight resident physician, I helped to make him more comfortable on his journey home.

September 4th, 2015

Time Flies

Raktim Ghosh, MD

Raktim Ghosh, MD, is a 2015-16 Chief Resident at St. Vincent Charity Medical Center, in Cleveland, Ohio.

We are approaching another September 15. This date is probably the second-most important in the U.S. residency application and selection season; the most important is obviously the match day. But, on September 15, residency applicants can start sending their applications to Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) accredited programs through Electronic Residency Application Service, and programs can also start downloading the applications. Nowadays, it is crucial to apply early to the programs. Some of them screen applicants on a rolling basis and start scheduling interviews as early as in mid-October.

For me, this brings back memories of September 2012, when I applied for residency. Working on my ERAS residency profile started a month before. It included writing my personal statement, choosing appropriate programs, uploading my CV, and sending letters of recommendation to the Educational Council for Foreign Medical Graduates. Like many other international graduates, I was also part of a USMLE residency forum on a popular social networking site. The forum members posted immediately as programs started sending interview requests. Then came those days when I refreshed my email every 30 minutes for any possible interview invitation. A 2013 survey by National Residency Matching Program showed that U.S. medical school seniors who successfully matched in residency usually attended a median 11 interviews. After interview confirmation, it was all about booking bus or flight tickets — finding the cheapest bus or plane fare and the closest reasonably priced hotel to the hospital. The entire process of interview travel was very grueling, exhausting, and expensive. I remember finalizing the answers of prototype residency interview questions while driving to the interview: Why internal medicine? Why our program? Why this city? Where do you see yourself in 5 years?

For me, this brings back memories of September 2012, when I applied for residency. Working on my ERAS residency profile started a month before. It included writing my personal statement, choosing appropriate programs, uploading my CV, and sending letters of recommendation to the Educational Council for Foreign Medical Graduates. Like many other international graduates, I was also part of a USMLE residency forum on a popular social networking site. The forum members posted immediately as programs started sending interview requests. Then came those days when I refreshed my email every 30 minutes for any possible interview invitation. A 2013 survey by National Residency Matching Program showed that U.S. medical school seniors who successfully matched in residency usually attended a median 11 interviews. After interview confirmation, it was all about booking bus or flight tickets — finding the cheapest bus or plane fare and the closest reasonably priced hotel to the hospital. The entire process of interview travel was very grueling, exhausting, and expensive. I remember finalizing the answers of prototype residency interview questions while driving to the interview: Why internal medicine? Why our program? Why this city? Where do you see yourself in 5 years?

Now, being a chief resident, I am part of the core team that will select next years’ residents. I can see the enormous work our graduate medical education staff puts to streamline the recruitment process. It’s not easy to identify suitable interview candidates from a pool of close to 3000 applicants. Today, I’m on the other side of the table. Our interview selection is not based just on good USMLE steps scores but also on research and publication experience, good letters of recommendation, and prior U.S. clinical experience for international medical graduates. I, along with my two co-chiefs and the GME staff, are currently busy outlining program selection criteria, updating the residency website, making slides for presentations, and preparing on interview schedule. I close my eyes for a moment and can vividly remember my interview experience with the same program director and core faculty 3 years back: It was a mixed bag! It’s an extreme honor and responsibility to sit next to the same people who brought me into this program and to help them choose the best suited candidate for next year. This enormous administrative experience is probably the most enriching lesson of my chief residency year.

I would like to send my best wishes to all the 2016 residency candidates. Good luck!

August 28th, 2015

How Do You Teach Art?

Andrew Ip, MD

Andrew Ip, MD, is a 2015-16 Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia.

When I first applied for medical school, I beamed about exploring not just the science of medicine, but also the art. But what is that art? Some would say it’s clinical experience, combined with being cultured and compassionate and communicating with clarity/conviction. But how would one teach that art?

Journal Watch’s Dr. Allan Brett recently reviewed a multicenter US study following ~300 metastatic cancer patients who had failed initial chemotherapy (NEJM JW Gen Med Aug 6 2015). The study showed that additional chemotherapy for patients with poor life expectancy <6 months had no better quality of life or prolonged survival. In fact, patients who had the highest performance status had worse quality of life when given additional chemotherapy.

Even with our remarkable scientific discovers in medicine, we still have a very tough job to deliver the science of medicine in a patient-centered format. Oftentimes, it is a judgment call to decide if a patient with end-stage liver disease or heart failure or COPD or cancer would benefit from any additional aggressive treatment. From my experience, many patients, and their families, are initially resistant to accept a terminal prognosis and want to pursue aggressive measures. What happens next involves a moment in which the physician can analyze the situation, with risks/benefits in mind from a scientific point of view, and then deliver a message that keeps the patient’s goals of care in mind while also informing the patient that you do not wish to harm them with interventions that may be not in their interest. This is one of the toughest things to do as a clinician, often leading to many of us tip-toeing a fine line.

One story that has stuck with me from residency is the story of Mr. G, an Ethiopian patient. Mr. G had end-stage cardiomyopathy and had been in the hospital for 3 months while on inotropes. Unfortunately, he did not qualify for any advanced heart failure therapies. As our team was trying to explain the dire situation, he initially wanted all aggressive measures. He also said to me, “please, don’t tell my wife and children.” He squeezed my hand as he spoke to me, and I squeezed back.

As a clinician who prides myself on my empathy and compassion, this was one instance where I had to go against honoring all of my patient’s wishes. Our team felt aggressive measures would not give any quality of life and would likely lead to more harm than good. We also contacted his wife and children to inform them their loved one was going to die soon. This was the most difficult part, as Mr. G was extremely upset from a cultural and personal standpoint that his family knew his prognosis. It was a judgment call that, because I misunderstood the cultural implications, fractured my physician-patient relationship with Mr. G at the time. However, I did not give up on delivery of care, and I treated Mr. G and his family as my own family — and a remarkable turnaround occurred in our relationship. His children delivered a card and flowers to me, thanking me for all the personal care I gave to their father, and Mr. G embraced me as his physician, holding my hand yet again. Mr. G died peacefully 2 days later, with his family at his bedside.

Maybe the art of medicine is not something you teach. Maybe it is an individual style you develop with experience with direct patient care or with role models and mentors. But what we often forget is the patient should be at the center of anything we deliver in medicine. That may be the art.

I would love to hear thoughts from others about their experience developing their own art of medicine, or in scenarios where sometimes treating a patient may have caused more harm than good.

August 25th, 2015

Motivations of a Doctor in Training

Ahmad Yousaf, MD

Ahmad Yousaf, MD, is the 2015-16 Ambulatory Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School.

As my co-chiefs and I try to figure out how to best serve our residents and deliver a worthwhile education to them, I have begun contemplating what it is that really motivates doctors in training. What is the driving force behind a resident striving to be a more knowledgeable clinician? How do we convince them that they need to work hard and take an immense amount of time and exert an enormous amount of effort to acquire both the didactic knowledge and the clinical sense required and expected of them by their profession and patients?

After a lot of thought and discussion with colleagues, I have found that the drive for each resident is a unique combination of 4 major factors; every resident’s makeup varying the exact ‘amount’ of ingredient that needs to be tapped into to make their training experience worthwhile and productive:

- Fear/Guilt… That knot in the pit of your stomach… that globus sensation that makes it impossible to swallow… that nightmare that wakes you up in the middle of the night as you replay all of the things you missed earlier in the day. It is the fear of killing someone — a drive that is so potent that it leaves residents googling the side effects of the Benadryl they just prescribed as they sit on the toilet between bouts of irritable bowel syndrome at 2AM. This fear and guilt is healthy, but, if not tempered at the beginning of residency, it can be all consuming and harmful. It is a powerful motivating factor when you recognize the immense responsibility that you have — that your order might permanently change the lives of another human being and his or her family.

- Signs that your resident is highly motivated by fear/guilt:

- Twitchy and nervous on rounds

- Frequent bathroom breaks

- Checking and then rechecking orders and notes the way Jack Nicholson checks his door locks in “As Good as It Gets.

- Shame… Do you remember when the teacher called on you and asked you a question that you definitely should have known the answer to, and you froze? Can you recall how you felt the warmth of embarrassment crawl up your chest, pass your palpitating heart, move through your almost completely closed throat and into your now red cheeks? Do you recall the deafening silence that you were responsible for weighing down on all your peers, and the 9-month-pregnant pause your teacher allowed to mature into a full-grown baby of shame and self-loathing? Do you remember thinking about that time over and over again and re-living the terror of that moment of humiliation? That is the moment of shame that drives some of your residents to read, to work harder, and to always be prepared.

- Signs that your resident is highly motivated by shame:

- Crumpled up notes in overstuffed white coat pockets

- Coming to the hospital 2 hours before the next resident for pre-pre-pre-rounds with multiple cups of coffee on board before the team attending has even rolled out of bed.

- Overly concerned about evaluations that peers and attendings spend about 4.7 seconds of mindshare completing.

- Ego… or the Id, if you want to get all Freudian on me. It is the impulse to want to be the best and to triumph over all others. This is the drive that makes you seek the admiration of all, the respect of those beneath you, and the recognition of those ethereal beings we know as attendings and administration. It is the desire to attain a status in which you can look in the mirror and say you did it and declare to everyone, or sometimes nobody but yourself, that you are the epitome of what a doctor should be. I also take the liberty of placing attainment of loftier position/money in this category of motivation — i.e., fellowship and dollar bills.

- Signs your resident is highly motivated by ego:

- Aspiring cardio fellow (likely a ‘gunner’ intern) that walks around with calipers in his pocket despite being on an outpatient rheumatology elective.

- Pristine white coat over an Armani suit, far too much hair gel or the clickiest shoes in town.

- The resident who takes every opportunity to quote obscure papers from Scandinavian research cohorts written in the 1950’s that almost never pertain to the patient or patient population at hand. Impressive? Yes. Clinically applicable? Never!

- Vocational Aspiration… Close your eyes and think about the physician you always wanted to be like. The one who gets down to eye level with his/her patient, speaks confidently about the matter at hand, shows love and compassion that cannot be faked or learned in a textbook, and exemplifies the characteristics of a healer. You see this in the resident who has taken medicine on as a vocation… as a calling. It is who they are and as a consequence, they take it as their responsibility and duty to strive for well-rounded excellence because, to them, there is no other option. This is the drive we strive for but only catch glimpses of when we are not devoured by our fears and shames and egos. If you ask every resident why they do what they do, they give answers that fall into this category: “I want to help people.” “I want to make people better.” “I want to make myself a better person and doctor.” It is what we write in residency application essays but seldom see in ourselves while in training. This is the most important motivator to trigger and mature in the residents we work with. All of the others are important tools to get people going, but without this, we are producers of machines and not physicians.

Factors/Motivators that deserve an honorable mention:

- Golden Child Syndrome

- “My parents made me do it.” You know these people. They were told what to do and are good at being told what to do.

- The Challenge

- The intellectual challenge of medicine drives so many physicians. The puzzle that a clinical case represents can be enough of a driver for some residents.

- Silencing the Naysayers

- There are some who do what they do because they have been told they cannot do it. Medicine…then Mt. Everest. See Ego for further detail.

- The Narcissist

- “Let me take a selfie while I sew up this laceration like a plastic surgeon.” Are you noticing an ego trend?

There are probably tons of other motivators you see that get people going. Share them in the comments and tell us the tell-tale signs that come with someone who is motivated by that factor.

~Yousaf