February 12th, 2016

What Have I Learned as a Chief Resident?

Raktim Ghosh, MD

Raktim Ghosh, MD, is a 2015-16 Chief Resident at St. Vincent Charity Medical Center, in Cleveland, Ohio.

At my institution, next academic year’s chief residency application email was sent out last week. The APDIM spring meeting for chief residents and program administrator is going to be held in Las Vegas in April 2016. The 2016 chief residents need to be selected before that meeting.

That e-mail brought a flashback memory for me. I met Charleen (the NEJM JW Resident blog editor) at the last APDIM meeting, and that’s how my association with ‘NEJM Journal Watch Insights on Residency Training’ started. I clearly remember walking up to the NEJM booth and seeing a card on a table that read ‘If you are a chief resident and interested in writing, please stop by.’ We spoke for a while, and I decided to apply. My journey as a chief resident and a blogger started at the same time. Now, I have finished 70% of my tenure as a chief resident and a blogger. It’s probably time for introspection about what I have learned during this journey and what I have delivered to my institution.

Last year at APDIM, I attended many different sessions, including morning report teaching, keeping residents engaged, making call schedules, preparing an academic calendar, addressing conflicts between residents, and dealing with difficult residents. I did not realize at that time that most of my learning would actually come in the form of real life experiences in all of these areas.

I surely have evolved into a more mature individual from dealing with these issues. It’s not just about what to say, but how to say it. It’s about what to write in an official email. How to get work done without offending the majority of people. How to improvise new teaching strategies to keep the audience engaged in different situations. Acquiring the ability to stay neutral and unbiased as an administrator and to maintain confidentiality.I learned to identify weak and strong people from a team and mentor them accordingly to achieve their individual goals. And, the most difficult situation I faced was saying no to my best friends’ call change requests but still hanging out together after working hours. I definitely see and appreciate the enormous amount of work done by graduate medical education staffs to run residency programs in academic institutions — working closely with people who have administrative roles has been an invaluable learning opportunity.

At times, I struggle to balance clinical work, study, administrative work, and family life. However, I am not complaining. This is what I wanted! I have enjoyed every day so far as a chief resident. So, a few more months of this, and then a new journey begins. What I have learned as a Chief Resident will stay with me for the rest of my life. If you’re thinking of becoming a Chief Resident, prepare yourself for a whole new learning experience, and enjoy every moment of it!

February 5th, 2016

Don’t Give Up!

Gregory Shumer, MD

Greg Shumer, MD, is a third-year resident and 2015-16 Co-Chief Resident at the University of Michigan Family Medicine Residency Program in Ann Arbor.

There comes a time in most people’s training when adversity threatens to become overwhelming and swallow them whole. It could be as a medical student, while spending countless hours in the library or when on demanding rotations. Or, it could be during residency, from the 80-hour work weeks or the stressful patient care situations. It might even happen well into training, when the weekly grind just becomes too much. Burnout, generally defined as “loss of enthusiasm for work, feelings of cynicism, and a low sense of personal accomplishment,” is more common among physicians than other American workers – 46% of physicians responded that they had feelings of burnout in a 2015 survey, with the highest rates occurring in physicians on the front lines of care, in specialties like emergency medicine and primary care.

When I was young, I wanted to quit everything I tried. It happened first at age 5. Tears welled in my eyes when I was unable to kick the ball correctly during my second soccer practice. The coach tried to help me, but the ball just wouldn’t go where I wanted it to. I was a stubborn child, and on this occasion, I stomped off the field after practice and cried all the way home. I told my mom I was never going to play soccer again. I took a pen and stabbed holes in my jersey to prove the strength of my 5-year-old will.

The next day, my mom and dad sat with me during breakfast, and calmly told me that despite my wishes, I was actually not going to quit soccer — that they wouldn’t let me. I was still angry, and I fought back. In the end, we agreed to a compromise: that I would finish the season, but afterwards, if I didn’t want to play anymore, I could stop. By the end of the season, I loved soccer. I played throughout high school, and I continue to play today in adult men’s leagues.

It happened again when I was 11, this time during summer camp. It was my first experience spending a significant amount of time away from home, at a sleep-away camp in northern Michigan. By day three, I was homesick and miserable. The other kids were too loud at night, and I couldn’t sleep. I didn’t like the food. The activities were boring. I wrote my parents every day, begging them to come pick me up. Again, my parents pushed back, reminding me that just a few weeks earlier I had begged them to go to camp in the first place and that I must finish my commitment.

In medical school, it very nearly happened again, this time threatening to end my medical career before it really even got started. I took a year off before starting medical school, working as an English teacher in Japan. Not only was it difficult for me to transition back into the role of student, but I also wasn’t prepared for the difference in intensity and volume of medical school work compared with undergrad. After 3 months of courses in anatomy and biochemistry, I was performing poorly and not putting in the time needed to succeed. I began feeling more and more overwhelmed, and those old tendencies that I had as a child started to creep in.

Maybe this isn’t for me, I remember thinking. I was so much happier in Japan, so much more carefree! Maybe I should quit medical school and go back… I could get another job as a teacher…

I thought back to those childhood lessons on the importance of perseverance. Instead of giving up, I decided instead to dig in and work harder, because I remembered why I entered medical school in the first place — my dream of becoming a primary care physician. I spent more time in the library. I joined study groups. I did extra practice problems and took more thorough notes. Better results came almost immediately. My scores improved, as did my mood. Now, nearly 7 years later, I am so relieved that I stuck with it. I am enjoying my final year of residency, and I’m excited about my future career as a family medicine doctor.Medical training is hard, no doubt about it. The hours are long, and the job can be demanding and stressful. Although burnout and stress are sometimes unavoidable, my advice from personal experience is to try to keep those feelings at bay when you see them approaching. If the stress becomes too much and threatens to overtake you, think twice before giving up. Maybe what’s needed is some personal time, a change of direction, or a conversation with someone you trust and admire as a mentor.

For me, what was needed during that first year of medical school was a long look in the mirror and a greater commitment to my long-term goals. And, I’m not sure I would have made the same decision without some timely lessons throughout my childhood.

Thank you, mom and dad!

February 3rd, 2016

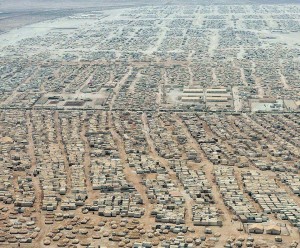

Zaatari: Day 3 with Syrian Refugees

Ahmad Yousaf, MD

Ahmad Yousaf, MD, is the 2015-16 Ambulatory Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School.

This is my third post about my trip to the Zaatari Refugee camp in Jordan with the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS). I will continue to share my daily journal entries with you in hopes of educating the American medical and nonmedical communities about what I saw, erasing the irrational fears that have guided the discussion of refugees in this country, and as a form of therapy for myself.

Reflections from Day #3 with Syrian refugees:

1) The Zaatari refugee camp is both a fascinating human achievement and, simultaneously, a mark of shame on the record of humankind. There are organized shipping container-like abodes set up in miniature communities, with tiny malnourished, barefoot children roaming the streets despite the freezing cold. The supply distribution system is impressive, but the condition of 80,000 innocent human beings stuck in a place far from the comforts of home is horrendous. There is a combination of hope and horror intertwined into the mundane life of waiting/surviving in this limbo — people seem to just stare off into space, daydreaming of a home that probably doesn’t exist.

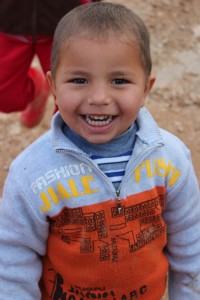

2) The human spirit’s ability to simply survive is remarkable. A living hell exists in this world, and children with nothing to be happy about and EVERYTHING to cry about, push through and flash peace signs and smiles. We were unworthy of those smiles but they graced us with wide eyes, excitement, and imagination we truly didn’t deserve.

3) The human touch in western medicine is severely underrated. Putting your hands on people, giving a big bear-hug, holding a child to your chest, shaking the hands of an elder respectfully… It is all we have to offer sometimes…

Photography by Amal Rass and Joshua Margaritondo

One Syrian refugee described the refugee experience as a “slow death.” He contemplated whether or not going back to Syria was better because, at least if he died, it would be swifter than what he and his family were experiencing at the moment. He spoke of his people coming together again, in heaven. The following is a poem inspired by that conversation in combination with the news of the siege of the city of Madaya in Syria.

The Slow

His cold fingers tighten around our necks, clasped,

The last bit of air escapes and with it hope, collapsed,

The deep sleep is to follow but the screams keep us from the Light,

Dreams of feasts call us closer to slumber, but the pains of hunger keep us up this night,

Our mothers’ hands run over our bellies to fill them, a mercy,

Our fathers take up arms against the devils, to kill them, bravery.

But they are murdered by the victory of a false god, an evil wrought,

We only have prayer, the bitterness of salt and water sustains us not,

He now surrounds us, his barrels facing the barrels of our chests,

Our ribs now part, what is inside now visible through the skin and bones of our breasts,

We are but target practice, our hearts the bullseye,

Our names unknown, our value mistaken, too dry to cry,

We see him now, his darkness begins its plodding embrace,

Squeezes us gradually, tightly towards his face,

We meet his eyes and know the suffering is soon to be done,

We now welcome his coolness and the calm that lays beyond, the One.

We go limp in his arms, and up goes an army of lifted souls,

He carries us from Zaatari and Madaya to another heaven above, an incomplete people to be again made whole,

And so the screams are replaced with laughter. Tears of joy, not despair, now fill our eyes,

The Slow Death has delivered us and now we indulge in the everlasting supply of His Love in Paradise.

~Yousaf

To donate to the Syrian American Medical Society, click this link http://bit.ly/1pmh8ZR and scroll down to Jordan missions.

If you have questions or are interested in volunteering, please reach out; even if you’re not in the medical field, you’ll be of help, especially if you speak Arabic.

January 29th, 2016

Zaatari: Day 2 with Syrian Refugees

Ahmad Yousaf, MD

Ahmad Yousaf, MD, is the 2015-16 Ambulatory Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School.

This is my second post about my trip to the Zaatari Refugee camp in Jordan with the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS). I will continue to share my daily journal entries with you in hopes of educating the American medical and nonmedical communities about what I saw, erasing the irrational fears that have guided the discussion of refugees in this country, and as a form of therapy for myself.

Reflections from Day #2 with Syrian refugees:

There were two moments today that are going to be hard to forget.

1) When I’m caring for children, I often make corny old doctor jokes with moms and their kids in the office in America. This day in the Zaatari clinic, two children with viral infections came into the exam room with their mother. Their mother, a woman in her mid 20’s, was concerned her kids kept getting sick. I asked if they played with a lot of other kids or go to school. She said that they are often with a lot of the other refugee kids. I made my ‘go-to’ joke: “At ages 4 and 6, children hate sharing anything with each other, except for the things we do not want them to share. They love to share their boogers and illnesses with each other, their mamas, and their papas …” There was a pause… It was heavy. I had  assumed that the children’s father was alive, not imprisoned, and not separated from his family in the escape from Syria. The mom’s eyes welled up with tears. “They don’t have a papa anymore.” The words hit me hard, and shame overwhelmed me. I thought of my own baby girl and the absolute terrible thought of her not having me to love her, care for her, protect her, and provide for her. I offered weak condolences and tried to refocus on the kids’ infections. Before they left, we stuffed extra lollipops in their pockets and gave them hugs. We can treat the infections, but how do you treat a problem that doesn’t have a cure?

assumed that the children’s father was alive, not imprisoned, and not separated from his family in the escape from Syria. The mom’s eyes welled up with tears. “They don’t have a papa anymore.” The words hit me hard, and shame overwhelmed me. I thought of my own baby girl and the absolute terrible thought of her not having me to love her, care for her, protect her, and provide for her. I offered weak condolences and tried to refocus on the kids’ infections. Before they left, we stuffed extra lollipops in their pockets and gave them hugs. We can treat the infections, but how do you treat a problem that doesn’t have a cure?

2) A mother came in with four children who all had chronic coughs and congestion issues. The mother was funny and warm, and when I asked her what her kids’ names were, she said the names of her three older sons and then the name of her youngest daughter, Shaam. She looked at us with a smile and said: “That is where we are from in Syria. We love that place, and my daughter is a reminder that we will love the day we finally get to go home with her.”

Shaam was born a refugee. She knows nothing of her homeland. Her entire life has been spent in a shipping container that has served has her temporary abode in the camp. May her parents’ wish be granted that she one day return to her namesake.

Shaam was born a refugee. She knows nothing of her homeland. Her entire life has been spent in a shipping container that has served has her temporary abode in the camp. May her parents’ wish be granted that she one day return to her namesake.

Photography by Amal Rass and Joshua Margaritondo

It has now been almost 2 weeks since my return, and I still have images of the children of Zaatari imprinted in my memory. I hold up my own 2-year-old daughter and look into her eyes, knowing that if I work hard, I will provide her with everything she ever needs. The children of Zaatari do not have that. Their fathers have been killed, imprisoned, or stripped of any opportunity to protect them or provide for them. Their mothers are left caring for entire families. (I saw one woman caring for 12 children, mostly nephews and nieces who had been orphaned.) Many of the caregivers are teens. The devastating war that has ravaged Syria is still ongoing — the factor that actively produces Syrian refugees is still happening. And for the most part, we do nothing. That feeling of hopelessness is immense.

To donate to the Syrian American Medical Society, click this link http://bit.ly/1pmh8ZR and scroll down to Jordan missions.

If you have questions or are interested in volunteering, please reach out; even if you’re not in the medical field, you’ll be of help, especially if you speak Arabic.

January 22nd, 2016

Today’s Medical Care — A Trap for the Sick and Elderly ?

Andrew Ip, MD

Andrew Ip, MD, is a 2015-16 Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia.

One of the great things about serving as chief resident this year is the opportunity to attend wards. Below is a short story about a patient that was admitted to my team for less than 1 hour, but whose impact on me will last the rest of my career:

In November, I had the privilege to take care of Mr. E. Mr. E had an anterior STEMI last summer with a resultant EF of 25%, leading to several heart failure (HF) exacerbations that required hospitalization. When we, the medicine team on call, were asked to admit him in late November for yet another HF exacerbation, my resident astutely noted he was cold and wet. I agreed, and we sent him immediately from the ER to the CCU to receive inotropic support. He never returned back to my team, but stayed in the ICU for more than 30 days. I visited him regularly in the CCU – he was always in good spirits, despite becoming inotropic dependent and undergoing a heart transplant evaluation.

On the 28th day of his hospitalization, a special occasion occurred – his 55th birthday. We had a heart-to-heart, and he expressed his desire to continue to live. I asked him what he meant by that, and he said he wanted to go home and to be with his family. That was ‘living’ for him. He expressed his strong belief in God, and he asked if I could pray with him, to which I agreed. Throughout his 36-day hospitalization, he underwent multiple procedures and diagnostic tests to see if he would qualify for a heart transplant, only to be denied. His hopes to return home and to be with his family were denied as well, as his condition quickly deteriorated with cardiac arrest from ventricular tachycardia (he survived that, however, after 1 shock) and multi-organ failure. Mr. E passed away on the inpatient palliative care floor at our hospital at 4 am on Christmas day, with no family at his bedside.

When I first started medical school, my naivete was that the art of medicine was practiced with the idea that the patient should be at the center of anything we deliver, as I wrote in August. Mr. E did not want to spend his last hours and days alone in the hospital, but that is exactly what happened to him. Why? I think now, 8 years after I started my journey into medical training, I’ve become jaded: I think that, despite what is preached in school and academic hospitals, most healthcare is still delivered with a culture of paternalism.

Perhaps a better way to say it is that medical care for our sick and elderly is a winding maze of never-ending appointments, procedures, treatments – a total trap. What do I mean by this? Once a sick patient is seen in multiple medical/subspecialty clinics, or admitted to the hospital and seen by multiple services, the patient, such as Mr. E, feels like he or she is at the mercy of what the doctor decides is the best course of action. Often, patients may not even realize, due to poor socio-economic status, that they have a voice in their care — an all-too-common scenario at my county hospital.

Another extension of our health care system, nursing homes, is another great example of how we trap our patients, this time the elderly, into an environment that caregivers and families believe is in the patient’s best interest. Often, this results in a total loss of control and alienation of our aging population, which (by the way) will only continue to become older AND healthier (Jagger C et al. Lancet 2015 – NEJM Journal Watch’s post) .

Atul Gawande wrote a fantastic book, Being Mortal, detailing his thoughts and sharing his stories about the perils of aging and modern medical care in today’s world. Topics mainly centered around how the sick and the elderly are treated more like inanimate check-lists or to-do lists, with providers focusing on fixing the disease or caregivers focusing solely on activities of daily living. He eloquently writes that our medical profession seeks to ensure health and survival, rather than “to enable well-being.”

*Please note, the next paragraph is heavily influenced by my recent viewing of the hit Netflix crime documentary Making a Murderer, which I HIGHLY recommend :)*

Recently, I’ve mulled in my head that a great parallel of our current healthcare system ‘trapping’ our sick and elderly once admitted to the hospital is our current judicial system ‘trapping’ an accused defendant who has a criminal past. Just like in healthcare, where many providers ask “how can we fix this disease?” and forget the patient, so do many in the court system ask “how can we convict this killer?” and forget the defendant is still presumed innocent until proven guilty. The medical team in a hospital has powers such as ‘medically holding’ a patient against their will, just like a judge can overrule a defendant’s pleas to throw out illegally obtained evidence. The physically afflicted and the accused – both deserve to have a fighting chance to preserve their well-being and innocence, but both can be trapped in systems that have different agendas.

How do we avoid this trap? I would propose a listen-first, treat-second approach to most of our patients, with shared decision-making being the ultimate goal. This is not a new idea, but certainly patients like Mr. E remind me I have to be much better at empowering my patients and advocating for them.

January 15th, 2016

Zaatari: Day 0–1

Ahmad Yousaf, MD

Ahmad Yousaf, MD, is the 2015-16 Ambulatory Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School.

“I am going to a Syrian refugee camp.”

The words came out of my mouth without hesitation, and my wife’s reaction is exactly what I expected… She already knew. After 5 years of marriage and 8 years of being stuck with me, she knew how I was going to react when I saw the medical mission video at the fundraiser to which we had been invited. I could not sit in my chair and watch the whole thing. My skin was crawling with guilt about how apathetic I had been until I saw this video. I jumped up and spoke to the presenter as soon as he finished, and I had pretty much signed up by later that evening. I had no idea what it entailed or what I was getting myself into, but it was a decision that has since significantly changed my view of the world.

The next several posts from me will be my daily reflections from my trip to the Zaatari refugee camp for Syrian refugees in Jordan with a nonprofit organization: SAMS (Syrian American Medical Society). I flew to Jordan on New Year’s Eve and returned a short 8 days later, although it felt like much longer. I type now from the comforts of my Rutgers Chief Medical Resident office, but, I assure you, my heart and mind are still with the Syrian refugees. The opinions expressed in this and the coming blog posts are mine alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of NEJM Journal Watch or the New England Journal of Medicine. I also make the following disclaimer: I am not Syrian, nor do I have roots in Syria. The purpose of my trip was unclear to me at the beginning, but as I return, my goal is much more clear: Let the world know what I saw and experienced. Let my medical and nonmedical family, friends, and colleagues know what it is I saw in the eyes of the Syrian refugees I treated and touched and interacted with. The pictures you see will be credited to those who took them (to the best of my knowledge). The most profound ones you will see are from Amal Rass, a journalism student from Chicago who accompanied the physicians of SAMS and did her best to document the realities of the camp and the refugees. Finally, before I begin… I ask you to share these posts with your family, your doctors, and your colleagues and reflect on the stories and pictures yourself. You may catch a glimpse of what we witnessed while we were there and it may affect you just enough to do something that will truly change things.

Reflections from Day 0-1:

1. (From JFK airport) I’ll be somewhere over the Atlantic when the clock strikes midnight and the year changes from 2015 to 2016. Most of us live an experience where there is some sort of value to one year changing to another. Some progression of something… an assumed movement forward. Refugees don’t have that luxury. When survival and hunger and warmth and escape are the only things on your mind, the only thing that matters is being right here, right now, in this moment… This moment is all we are promised and, for some, ‘next year’ is just a continuation of this moment and not something new to feel hopeful about or to look forward to.

2. We were picked up from the Amman Airport by SAMS personnel, one of them a Syrian refugee himself, but now employed by the nonprofit. We sat in the van and began introducing ourselves and asking about details on what the Zaatari camp was all about. It is now the 5th largest city in Jordan with 75,000-85,000 residents. At its peak 2 years ago, almost 250,000 people lived there. When asked what happened to all of those people, he said, “Some died. Some escaped to Europe. A lot of refugees went back to Syria. In the refugee camps, they were dying slow deaths. In Syria, it was fast death… fast death is better, I think.”

When we arrived in Amman, it was snowing… Warmth is a luxury.

3. The most important medications we dispensed today had nothing to do with the tons of donated meds we had available.

A hand on a shoulder, a smile, a little prayer, and some reassurance were far more effective. I require a translator most of the time to get some of the details… but the prescriptions are almost always nonverbal, unwritten, and intimate.

The most memorable patient we saw today was a young Palestinian boy, around 6 years old. He had to leave the country he was born in for fear of detention. We didn’t have to understand his language to appreciate the animated story he told about why he was here and not in his homeland. And despite the sadness of that premise, he smiled the entire time.

We will come back different people. The things we have seen cannot be unseen. The faces are imprinted in our memories, and theirs smiles are seared in our minds. As I finished up this post, I received a message from one of the residents who came with me on the trip, Dr. Eman Rashed. It was her second day back at work as an intern in Newark, and her message said:

“I wonder how long before I feel like I’m normal again. Seems like never.”

I could not agree more.

Photography by Amal Rass

To donate to the Syrian American Medical Society, click this link http://bit.ly/1pmh8ZR and scroll down to Jordan missions.

If you have questions or are interested in volunteering, please reach out; even if you’re not in the medical field, you’ll be of help, especially if you speak Arabic.

December 29th, 2015

Holiday Reflection

Briana Buckner, MD

Briana Buckner, MD, is a 2015-16 Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Once a year, we have this very exciting period of time filled with holiday fun. The holidays bring families together, children get excited for Santa Claus, and the parking lots of malls make you think really hard about every gift you are seeking to buy.

Despite all this excitement, the holidays can mean something a tad bit different for a resident or intern that is in the midst of medical training. Once residency begins, the holidays can be a shock and, for many residents, the first holiday ever spent away from family. What seemed to be an every-year occasion while in school becomes a prized possession when everyone can’t be off service at the same time. During my intern year, I finally I arrived home for New Year’s: I realized that I had not set foot in a mall since August, I had no gifts to give, and no one saved me any of our family’s famous Christmas banana pudding!

Since finishing residency, I have realized that residency creates a different definition of holiday fun. My holiday fun during residency was ugly-sweater day on the medicine inpatient service, late-night hot chocolate parties hosted by the night nurses, singing Christmas carols with my patients, and learning about funny holiday traditions of others who were also working on the holiday.

While I definitely longed for my family during those Christmas holidays in the hospital, I realize that I also built memories that still make me chuckle, and my appreciation for my family during the holidays has increased tenfold. I still tell my parents and friends about my patient who loved soul Christmas songs. After rounding with my team, I came back to see this special patient, and we listened to the Christmas radio station together. Within minutes, we were singing and dancing to the Jackson 5 version of “I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus” and James Brown’s “Santa Claus Go Straight to the Ghetto.” I never told my patient how much that moment meant to me and how much it comforted me that day. I felt as though I was right on my grandfather’s couch and enjoying my own family. In that moment my patient became my family, and I’m sure I became his as well.

For all the residents who must spend the holidays away from their own families… I’m want to say “thank you.” Thank you for stepping away from your own family to take care of the families of others. You will often feel overlooked, but you are appreciated. Your patients appreciate you more than you know. For many of them, you will definitely become their family this holiday, and they will forever remember you. Take a pause, enjoy a sincere moment with your patients, and remember to tell your family that you love them.

For all the residents who must spend the holidays away from their own families… I’m want to say “thank you.” Thank you for stepping away from your own family to take care of the families of others. You will often feel overlooked, but you are appreciated. Your patients appreciate you more than you know. For many of them, you will definitely become their family this holiday, and they will forever remember you. Take a pause, enjoy a sincere moment with your patients, and remember to tell your family that you love them.

December 18th, 2015

Morbidity and Mortality

Ahmad Yousaf, MD

Ahmad Yousaf, MD, is the 2015-16 Ambulatory Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School.

He nervously shifted in his position in front of the audience of his peers. His voice was a little shaky, and the few words trying to escape his lips were chewed and swallowed. He was narrating a case in which a colleague’s sense of urgency, or rather, her lack thereof, likely negatively affected his patient. She sat in the front row with her head down, scared that the presentation might eventually lead to the revelation she was the one at fault. That would not be the case.

This is Morbidity and Mortality (M&M) conference. Most attendings and chiefs will tell you that it is, far and away, the most valuable educational experience in residency… and I agree. It is a conference in which there is objective iteration of a case in which a physician, team member, or system error occurred. Emphasis is  on what could be done so that the error is never repeated. Sometimes, the issue is one that never affected a patient’s care but could have, in another scenario: a “near miss.” Other times, the conference focuses on an error that directly affected the welfare of a patient and, rarely, resulted in or contributed to the death of a patient. Classically, M&M felt like a firing squad in which elders in the hierarchy of medicine picked apart residents who always seemed to make the most egregious gaffes when faced with a room full of people pointing their figurative rifles. There was a lot of sweating and stuttering and apprehension. Thankfully, things have changed across the medicine academic realm, and M&M has changed from a blame game and target practice to a time to reflect and develop.

on what could be done so that the error is never repeated. Sometimes, the issue is one that never affected a patient’s care but could have, in another scenario: a “near miss.” Other times, the conference focuses on an error that directly affected the welfare of a patient and, rarely, resulted in or contributed to the death of a patient. Classically, M&M felt like a firing squad in which elders in the hierarchy of medicine picked apart residents who always seemed to make the most egregious gaffes when faced with a room full of people pointing their figurative rifles. There was a lot of sweating and stuttering and apprehension. Thankfully, things have changed across the medicine academic realm, and M&M has changed from a blame game and target practice to a time to reflect and develop.

Humans make mistakes, and doctors are human. Therefore, doctors will make mistakes. This paradigm must be acceptable for medical academia to have a culture that results in the production of competent and confident physicians. M&M conference is the teaching modality that makes an error… a mistake… a point of reflection and a motivator for improvement, not a finger-pointing blame game.

The presenter concluded his case presentation, and the room stayed quiet for a moment. The burden of that silence is immense. Somebody died, and one of us could have done a better job to try to prevent it. That burden often results in tears. Every doctor in the room knew what it feels like. We have all been there. We all have a personal M&M folder locked away in the recesses of our psyche that highlights our limitations, reminds us of the blunders we have made, and impels us to never make those mistakes again.

The boss in the back of the room broke the silence with a reflection after seeing the intern up front with tears in her eyes. “It is completely okay that you cry about the mistakes you have made when it negatively affects your patient. It means you care.” I thought about those words of wisdom and appreciated how important it is to have a safe venue, especially during residency, to regret something you have done. The conference concluded with a list of learning objectives everyone in the room should take to heart so that countless mistakes do not have to be made for the physicians in the room to gather insight. We succeed together, and we fail together. And then… back to the floors so you can do it better.

~Yousaf

December 15th, 2015

Frequent Flier

Ahmad Yousaf, MD

Ahmad Yousaf, MD, is the 2015-16 Ambulatory Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School.

The name of the patient has been changed to preserve his privacy.

“Donald passed away.”

We had been sitting in the chiefs’ office with a few of the attendings who had all had Donald on their service at one time or another. Everybody exhaled a collective sigh, soaking in the sting of the knowledge of Don’s death; then, within a few seconds, everybody had smiles on their faces. The smiles were born out of a personal experience with him in the hospital. He was a special man. He was a dogged veteran who had fought in two wars: Vietnam and the war against the disease and illness that riddled his body. His words were rarely sweet, his blood pressure was always through the roof, his bone marrow had burned out to MDS, and his kidneys had begun giving up under the stress of his uncontrolled diabetes. On top of this, he was never adherent to his prescription regimen and medical recommendations.

He was the quintessential ‘frequent flier.’ When you saw his name on your patient list in the morning, you were usually unsurprised, a little frustrated, and somewhat satisfied you would see again the familiar, hardened face of a man who ‘wouldn’t take nothing from no one.’ Despite the difficulty in dealing with his tenacious personality, he always left you with a smile on your face — whether out of incredulity or amazement.

The attendings in our office began to share some of their stories about Donald:

“You know, once I had to bribe Donald with donuts so he would let us transfuse some blood.”

“You know, once I had to bribe Donald with donuts so he would let us transfuse some blood.”

“Once he was in renal failure because he had an overenlarged prostate, and when I told him we needed to put in a Foley catheter to relieve the pressure, he looked at me sternly and said, ‘you know, Doc, friends don’t hurt friends’.”

“One day I found him with a bucket of KFC despite strict sodium restriction recs, and I asked the nurses what happened. They told me there was no way they could stop Donald from doing what he wanted when he put his mind to it.”

“One day I found him with a bucket of KFC despite strict sodium restriction recs, and I asked the nurses what happened. They told me there was no way they could stop Donald from doing what he wanted when he put his mind to it.”

“He was always hungry. He would tell the techs to get him Chinese food secretly and would give them a couple of extra bucks for egg rolls so they would keep their mouths shut.”

I listened to the stories, and in my heart, I thought that Donald would have gotten a kick out of knowing we were remembering him this way. I thought about how I would like to be remembered. Hopefully, the day I leave this world, some people I care about will have some good stories to tell about me that will make them laugh and think and reflect.

Donald lived his life the way he wanted. He was pathologically stubborn and irritatingly argumentative, but he still had that bit of charm that showed through most in the moments when he was most ill. Donald should have died long before today, but he was too stubborn, even for death. He clawed and scratched every last breath and every last heart beat in this world, and he left a mark on all of us. We all knew that this day was coming. That we would hear that Donald had finally met his maker… and just like the countless times we saw his name on our patient list, we were unsurprised, we were a little frustrated, but we had little smiles on our faces.

Rest in Peace.

November 27th, 2015

A Generation of Softies

Ahmad Yousaf, MD

Ahmad Yousaf, MD, is the 2015-16 Ambulatory Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School.

I watch as my almost-2-year-old daughter awkwardly climbs the stairs. I do not hold her hand, but I do not turn my back on her either. She is still clumsy, and her little bowed legs often miss their targeted landing spots. She holds on to the rail with a vice grip that steadies each monumental step forward and upward. Every so often she wobbles as she miscalculates the distances and her toes barely catch the edge of the next step. Her knuckles become white as she reorients herself, recalculates her next move, and ensures she does not tumble backwards. My palms sweat and my muscles tense during every mishap and sway… I want her to get to the top… but just as importantly, I want her to do it herself. After she regains her composure from a mini-spill, I cheer, “Good Girl!” I am close enough to catch her if she falls all the way down but not close enough that she can use me as a crutch to get where she needs to go. I think she senses this, and it gives her just enough confidence to keep going. Every fiber in me wants to get up and carry her the rest of the way, but I know the consequences down the road: She will always expect me to do it for her. She will cry and whine and, when it gets too hard, good old Baba will come to the rescue and move her to safety. She gets to the top and turns to look at me. I consciously look away as if I wasn’t watching her every move. “Baba… up!” The grin on her face makes me fall apart, and I run up the stairs and tickle her until she cannot breathe.

This is an everyday occurrence with her. Sometimes she fails and cries and looks up at me with her big green eyes begging for a hand to Providence (at which point I melt like any man would and give in to her tiny wishes) and other times, she gets back up by herself and tries again… and gets the job done.

I want her to be safe, but I do not want her to be ‘soft.’ This is the dilemma that most physicians in the academic realm struggle with every day in training the new generation of doctors. Psychology Today recently published an article that discussed what seems like an epidemic of individuals in college who are unable to cope with even the simplest unavoidable day-to-day adversities.

Although the article dismisses the fact that, historically, most psychosocial troubles that students faced were undiagnosed and swept under the rug and that the increase in numbers of those seeking help may just represent a generational recognition of the needs for those services, it still surfaces a serious concern. Many people in teaching/training positions in the medical academic realm believe that many medical students and residents lack resilience and self-sufficiency. With much discussion focusing on how to decrease burnout, increase physician (and docs in training) access to psych support, and better resident well-being, are we in danger of going too far the other way? Are we setting ourselves up for a generation of ‘soft’ doctors who lack the ability to handle the stress of an occupation defined by its intensity? Internists come face to face with mortality, familial strife, and enormous amounts of emotional distress, all while being expected to remain calm, cool, collected, and objective. The reality is, it’s the physician who is expected to carry the brunt of the stress and mold plans of action for multiple patients every day. Can a ‘soft’ doctor handle that level of responsibility? SHOULD a doctor handle that responsibility?

Then the question becomes: How do we turn out quality physicians who are armed with the tools (knowledge, skill, AND personal fortitude) from training systems in which the major concern is preventing burnout? This question is difficult, and the process will alienate many as being ill-equipped to handle the job.

Finding the balance between developing physicians with the capabilities needed to handle the realities of the job AND not burning out a large portion of them before they even get so see a patient autonomously must be the focus of those who control the avenues of training. I do not have a good answer for this question — both endeavors are extremely vital for the future of medicine. Perhaps the answer can be found somewhere in the tale of how a parent deals with his or her child climbing the stairs: letting them take risks, experience the consequences, know the taste of failure, encourage persistence, and celebrate eventual success. All I can say for certain is that the best part of parenting is when you get to celebrate with them when they’ve reached the top.

~Yousaf