April 27th, 2016

A Shift Towards Well-Being

Charity Maniates, MSPA, MPH, PA-C

The elders sit in the communal living space, dotted with mismatched chairs, a small table scattered with newspapers, and the constant haze of fluorescent lighting. The nurses’ station, like a miniature watchtower, sprawls in the living space. CNAs cluster near the nurses’ station; their laughter is intermingled with the reporting of the day’s events and tasks to be completed. Nurses sit at the computers, focused on rapidly finishing their charting, or rushing to process orders and completing care plans. The medication carts stand like dreary beacons in the midst of the community room, staff opening the drawers exposing the stacks of pill packets for the shift medication count. Adding to the pulsing of noise is the high-pitched ringing of the unit telephone that no one has time to pick up. The unit doors are flung open, welcoming the constant flow of traffic from visitors, kitchen staff, providers, and others walking purposely through the residents’ living space. The elders sit watching, uncertain how to respond to the actions, sounds, and influx of new people.

The atmosphere crescendos and intensifies, washing over the residents sitting in rocking chairs or self-propelling aimlessly on the unit. One resident, a vocal and ambulatory individual, stands up, grabs her walker, and angrily storms over to another resident telling her to keep quiet and attempts to strike her. This elicits reactions from residents from tears to yelling — in particular, a commanding order from a feisty, lovable woman with dementia to “LEAVE HER ALONE!” that reverberates above the others. A few staff intervene and attempt to redirect the agitated woman to another chair. Another woman approaches the nurses’ station and anxiously asks,” I’m not sure what I do? Where do I go next?”

A man with advanced dementia sitting quietly in his wheelchair, who only communicates in unintelligible sounds, starts singing loudly at the top of his lungs. A 101-year-old resident approaches the nurses’ station, adeptly maneuvering her electric wheelchair around the tangle of people, demanding repeatedly to the nurse, “I want you to call my daughter, tell her to come pick me up and bring me to camp!” Her request seems quite reasonable. Why wouldn’t she want to escape the chaotic environment and head to her camp on a lake in northern Maine? I certainly would if my home were invaded daily by unfamiliar faces surrounding me.

At numerous moments throughout the day, including change of shift, nursing home residents are bombarded with stimuli, unfamiliar faces and schedules. Layer on hearing and visual impairments, and the ability to process simple daily interactions through language and body cues becomes quite complex. Because dementia blunts the ability to vocalize needs, simple reactions are perceived as “agitation.” Often the solution is a black-label antipsychotic that quells agitation by causing oversedation. Understanding the individuality of each patient helps to identify triggers of irritation, pleasure, or soothing. Contrary to current perceptions, this approach doesn’t take extra time or intensive training.

Nursing homes, federal systems and the outdated policies overseeing those systems haven’t changed much in the past 50 years. Organizational change and research efforts are excruciatingly slow. So, what can we do now?

Recently, I had the opportunity to hear the insights of Dr. Allen Power, a physician and internationally known advocate of the Eden Alternative, an approach to addressing dementia behaviors through changing nursing home culture towards person-to person approaches and away from medications. This model features seven foundational tenets of caring for elders with dementia that, if addressed, reduce perceived “negative behaviors:”

IDENTITY—being well-known; having personhood; individuality; having a history

GROWTH—development; enrichment; expanding; evolving

AUTONOMY—liberty; self-determination; choice; freedom

SECURITY—freedom from doubt, anxiety, or fear; safety; privacy; dignity; respect

CONNECTEDNESS—belonging; engaged; involved; connected to time, place, and nature

MEANING—significance; heart; hope; value; purpose; sacredness

JOY—happiness; pleasure; delight; contentment; enjoyment

Ultimately, focus is diverted to the individual and their well-being, rather than to the specific task at hand. The result? A more meaningful interaction and role for both the elder and those providing daily care.

For more on these seven domains of well-being in dementia care, below is a short video clip of Dr. Power:

April 20th, 2016

Wave

Harrison Reed, PA-C

On the road ahead, a silhouette appears between the blinding rays of sunlight, bouncing to a familiar pulse. As the figure approaches, you can only think of the air passing in and out of your lungs, the ache of your feet, and the heat that sizzles the back of your neck. But just before that other runner passes, you do something that an exhausted person in any other circumstance would find ridiculous.

It might seem strange to onlookers. Nobody waves to strangers anymore. But for two passing souls on a lonely stretch of road, that little greeting is an unwritten tradition in running.

I sometimes wonder why it seems so natural. The impulse to give that bit of humanity to a traveler passing the opposite way doesn’t require thought or planning. It just happens.

Like all instincts and reflexes, it must come down to survival. After all, out on a desolate road, as the miles tick by, there is no help if something goes wrong. If your ankle turns the wrong way, some hidden debris pierces your foot, or an internal organ decides to fail, your very survival could depend on a passing stranger. So maybe you wave knowing that you might be that person’s sole lifeline.

And he might be yours.

But that rule of the open road is often absent in medicine. It’s easy to forget that the bustle of a crowded ER or a busy ICU can be just as isolating as the most remote trail. And sometimes that other runner’s broken ankle or dehydration isn’t obvious. In healthcare, we push those wounds deep beneath the surface.

Every runner knows you have to run your own miles. And in medicine, you can’t shoulder someone else’s burden. But you can look ahead, far down the road, and spot a silhouette bounding along in your direction. You can make sure they are still putting one foot in front of the other.

And you can wave.

April 13th, 2016

How Do You Treat an Epidemic?

Elizabeth Donahue, RN, MSN, NP-C

A few weeks ago, I met my fourth new patient of the day, a man transferring care from out of state and needing refills on all of his current medications. That list happened to include suboxone for the simultaneous treatment of the chronic pain he experienced from a remote traumatic brain injury and the substance use disorder he suffered as a result of treating that pain with opioids for years. Because he had been receiving his medication from his former out-of-state provider for the nearly two months it had taken him to find a primary care provider in Massachusetts (see my previous thoughts on that topic here), he was due for refill on his suboxone within a week of his visit with me. Herein lies a major problem: I want to be able to provide this essential treatment for this patient and so many like him, but as a nurse practitioner, I cannot obtain a DEA X license that would allow me to do so. And even in a well-resourced state like Massachusetts, I fear that this patient will face barriers to continuing his treatment and may relapse.

Despite this hurdle, I was feeling optimistic about my ability to care for this man and others going forward because I was signed up for a health policy workshop dedicated to learning about the opioid crisis and how clinicians can understand the trends and “bend the curve.” Arriving at the workshop, I sat down eager to learn and soon found myself stunned by the breadth and depth of the opioid abuse epidemic. I also felt a bit irresponsible that I hadn’t educated myself earlier and gotten involved sooner. So here’s what I learned, and how I hope all clinicians can help.

We were welcomed by Dr. Monica Bharel, Commissioner of the MA Department of Public Health, who shared some information about the source of the problem. It was not surprising to learn that a great majority of substance use disorders start with the prescription of opioids. However, it was surprising to hear that most of these opiate prescriptions in Massachusetts are initiated by primary care providers — not surgeons or specialists, but providers like me.

Next, we heard about the scope of the problem based on some data from the CDC — how overdose deaths outnumbered traffic deaths in 31 states in 2010 (up from only 10 states in 2005). The statistics about how many people are suffering became even more overwhelming when I learned that the deaths only scratch the surface of how widespread the problem is. Each death is representative of approximately 32 ED visits for misuse/abuse, and each death represents nearly 130 people who misuse opioids or suffer from opioid use disorder that has not yet escalated. Finally, we heard about shortcomings regarding current solutions to the issue: Only physicians can obtain a waiver to prescribe needed agonist medications to treat opioid use disorder, yet only 1–5% of physicians in each state have applied for and obtained the license needed to prescribe this life-saving treatment, and those physicians are limited to treating 30 to 100 patients. More surprising statistics from my own research included this: Only 50% of addiction treatment centers offer medications, and in those that do, only 38% of patients deemed in need of treatment are offered it.

Thankfully, the speakers moved toward solutions that have already demonstrated success. And I was grateful to hear that there are a range of possible options — from those that can be implemented immediately (without too much pain for already overburdened primary care practices) to long-term solutions currently in the works. An NP colleague from the North Shore, Christine Malagrida, discussed how her practice uses screenings for alcohol use, drug use, and depression at all new patient appointments and annual physicals and then follows up with motivational interviewing techniques and suggestions/resources for the patients who screened positive. Of course, it’s important to know the resources in your area before implementing patient screening for substance use disorder, so that if you uncover an issue, you can direct your patient appropriately.

One model practice initiative in Massachusetts was presented by Colleen LaBelle, a leader in substance use disorder work in Massachusetts and Director of Boston Medical Center’s Office Based Opioid Treatment with Buprenorphine program. The program focuses on a collaborative teamwork model that supports physicians who prescribe agonist medications by providing patient care via nursing staff, case managers, social workers, and others who can address the many other physical and mental health concerns of patients undergoing treatment. This initiative has dramatically decreased ED visits and hospital admissions among those receiving treatment and has increased the number of patients receiving treatment from 0 to >8000 between 2007 and 2014. This type of initiative should be studied and replicated.

The most encouraging news was about two pieces of legislation that should dramatically increase access to medical treatment of opioid use disorder. The TREAT Act filed by MA Senator Markey would remove artificial barriers that currently limit the number of patients whom physicians can treat, thus allowing more patients to get the care they need from MD providers. President Obama also recently included a $1.1 billion budget line item dedicated to pilot projects that would extend DEA X waivers to nurse practitioners and physician assistants (in states that already have controlled substance prescriptive authority) in order to expand the numbers of prescribers who are able to treat patients needing suboxone for substance use disorder. Nearly 33% of NPs surveyed indicated that they would be willing to prescribe this type of medication. Also, projected growth of NPs and PAs by 2020 is 30% and 58%, respectively (compared to 8% for physicians), so this is a group with a demonstrated interest and growth rate to support a real-time increase in access to care for patients who need it.

The most encouraging news was about two pieces of legislation that should dramatically increase access to medical treatment of opioid use disorder. The TREAT Act filed by MA Senator Markey would remove artificial barriers that currently limit the number of patients whom physicians can treat, thus allowing more patients to get the care they need from MD providers. President Obama also recently included a $1.1 billion budget line item dedicated to pilot projects that would extend DEA X waivers to nurse practitioners and physician assistants (in states that already have controlled substance prescriptive authority) in order to expand the numbers of prescribers who are able to treat patients needing suboxone for substance use disorder. Nearly 33% of NPs surveyed indicated that they would be willing to prescribe this type of medication. Also, projected growth of NPs and PAs by 2020 is 30% and 58%, respectively (compared to 8% for physicians), so this is a group with a demonstrated interest and growth rate to support a real-time increase in access to care for patients who need it.

Inspired to change my practice by this incredibly informative and empowering workshop, I returned to my office the next day. My first patient arrived at clinic under the influence of heroin, which was reported to me by my medical assistant, who completed a routine screening on the patient as part of intake. I was glad to have at least the basics in place, to be asking the right questions, and also to have incredibly knowledgeable and compassionate staff with whom the patient felt comfortable being honest. The patient discussed with me that she has been using heroin daily for the last 4 months after her previous primary care doctor discontinued her prescription for oxycontin as treatment for her lower back pain and a neighbor offered her street drugs as a substitute. She expressed a sincere desire to stop using heroin and find a more appropriate treatment for her back pain, but also felt defeated at the stigma she had experienced at the hands of previous providers. (What could have reinforced the need for opioid abuse treatment to me better than this patient?) Thankful for the assistance of a social work colleague but cursing the delays in legislature and stigma surrounding this problem, I will do my best to care for her with the help of waivered physician colleagues as part of the team. In the meantime, I have signed up for the necessary training so that when the time comes when I can apply for a DEA X license, I will be ready. I hope that you, my provider colleagues, will consider it too.

Below are sources of information on both the staggering statistics and available resources. Though I am by no means an expert on this topic, I now realize that the scope of the opioid abuse problem — which is now THE number one cause of preventable death in the U.S. — is far too large to stand back and watch someone else solve.

Practical resources for providers:

Information and Application for DATA Waiver (DEA X license to treat)

Safe Opioid Prescription Education

Overdose Prevention and Nalaxone Rescue Kits

Screening and interview tools:

- AUDIT http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Audit.pdf

- PHQ 9 http://www.phqscreeners.com/sites/g/files/g10016261/f/201412/PHQ-9_English.pdf

- DAST http://www.bu.edu/bniart/files/2012/04/DAST-10_Institute.pdf

- SBIRT http://www.masbirt.org/sites/www.masbirt.org/files/documents/toolkit.pdf

Reference Sources and Articles of Interest:

- CDC National Vital Statistics System, Multiple Causes of Death. 2010

- The Future of Nursing Institute of Medicine Report. 2011

- HRSA, Health Workforce Analysis. 2013

- CDC/NCHS National Vital Statistics System NCHS Data Brief. March 2015

- SAMHSA Substance Abuse and Mental Health Data Archive. 2016

- Dart RC et al., Trends in Opioid Analgesic Abuse and Mortality in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 2015.

- E. Clark et al., The Evidence Doesn’t Justify Steps By State Medicaid Programs To Restrict Opioid Addiction Treatment With Buprenorphine. Health Affairs, 2011.

- LaBelle et al., Office-Based Opioid Treatment with Buprenorphine (OBOT-B): Statewide Implementation of the Massachusetts Collaborative Care Model in Community Health Centers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 2016.

- Walley AY et al., Office-based management of opioid dependence with buprenorphine: clinical practices and barriers. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2008.

Special thanks to:

Colleen T. LaBelle MSN RN-BC CARN

Program Director STATE OBOT B

Executive Director MA IntNSA

Laura G. Kehoe, MD, MPH

Assistant Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital

Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School

Medical Director, MGH Substance Use Disorders Bridge Clinic

Christine Malagrida, RN, MSN, CNP

Chief Operating Officer

North Shore Community Health

Monica Bharel, MD, MPH

Commissioner

Massachusetts Department of Public Health

Kiame Mahaniah, MD

Chief Medical Officer

Lynn Community Health Center

Christopher Shaw, NP

NP Team Leader

Addictions Consult Service, Massachusetts General Hospital

April 6th, 2016

Providers Need Care Too

Scott Cuyjet, RN, MSN, FNP-C

Granted, every situation is different and should be assessed prior to showing emotion or drawing a parallel to one’s own or another patient’s experience. In an emergency, there is often no time for this until after the event is over, and although a provider’s actions should still be guided by kindness and empathy, an emotional decision could be fatal. However, in non-emergency encounters, when someone is telling me a story about being abused, for instance, it can be appropriate and necessary to feel and express some emotion in a show of empathy to assist the healing process.  Patients want to know that their provider is human and not an automaton. Sometimes I generalize information about other patients who have experienced a similar health situation so that a patient doesn’t feel so alone and isolated. Other times, I share my own experience — as a teenager growing up and getting into trouble, or as a parent of teenagers — with my teen patients and their parents to make the point that things kids do during adolescence don’t always define who they will become later in life. Ultimately, as providers, we have to do what feels comfortable and comes naturally to us so that it does not come across as awkward or forced and have the opposite effect of making a patient feel uncomfortable.

Patients want to know that their provider is human and not an automaton. Sometimes I generalize information about other patients who have experienced a similar health situation so that a patient doesn’t feel so alone and isolated. Other times, I share my own experience — as a teenager growing up and getting into trouble, or as a parent of teenagers — with my teen patients and their parents to make the point that things kids do during adolescence don’t always define who they will become later in life. Ultimately, as providers, we have to do what feels comfortable and comes naturally to us so that it does not come across as awkward or forced and have the opposite effect of making a patient feel uncomfortable.

Given that I feel this way as a clinician, I was surprised when I recently found myself specifically not sharing my emotions as the family member of a critically ill patient, my grandmother. I was away from my home and family, helping to guide my mom who had power of attorney, and I realized that I was not allowing myself to feel. When hospital staff or family members asked how I was doing, I would give an analytical response about my grandmother’s condition and why this was the appropriate course, which helped me avoid my feelings, as I did not want them clouding my judgment. Given the emotional intensity of the situation, and my lack of sleep from sleeping in a chair in the ICU, I was starting to break down from the inside as well as the outside, which made me less capable of supporting my mom, who needed it the most. I also had not been able to run, bike, or go to yoga class as I do in my daily routine. When my grandmother was transferred out of the ICU to the floor, a nurse asked me how I was doing, and I finally broke down and told her how I was feeling. It felt really good to put down the weight I had been carrying so that I could continue to take some of the burden off my mom. As I walked away, I thought about how nurses also need to be nursed sometimes, not just patients.

Sometimes it is difficult to accept help when you are a helper. But it is hard to help others heal when we are in pain ourselves, so it is important that we clinicians make sure we take time for self-care.

March 29th, 2016

The Fringe: Part 1 – Negotiation Basics

Bianca Belcher, MPH, PA-C

In this series, with input from some financial industry experts, I will be addressing the four most common topics that I am asked about by PA students and experienced PAs who are transitioning roles or jobs. This series is meant to give you a basic idea of each topic and empower you to seek help and ask questions regarding your own personal finances. The topics are:

- Negotiation Basics

- Debt Management

- Deciphering Your Benefits Package

- Retirement Contributions

Let me start by saying that I’m not an expert in negotiation, but I have done a lot of research on the art of negotiating, interviewed experts in the field, and helped dozens of PAs negotiate their contracts. I first became interested in negotiation when I realized that I had no idea what I was doing. The whole process seemed so complicated that I basically accepted defeat before it even started. Negotiations are awkward. No one likes discussing money with a total stranger, but if you don’t ask for what you want– rest assured – they won’t offer. You won’t always get everything you ask for; in fact, sometimes you may not get anything, but the point is — if you don’t ask, you’ll never know. Over time, I have developed a few tips designed to increase your comfort level with the negotiation process and enable you to have reasonable expectations.

Let me start by saying that I’m not an expert in negotiation, but I have done a lot of research on the art of negotiating, interviewed experts in the field, and helped dozens of PAs negotiate their contracts. I first became interested in negotiation when I realized that I had no idea what I was doing. The whole process seemed so complicated that I basically accepted defeat before it even started. Negotiations are awkward. No one likes discussing money with a total stranger, but if you don’t ask for what you want– rest assured – they won’t offer. You won’t always get everything you ask for; in fact, sometimes you may not get anything, but the point is — if you don’t ask, you’ll never know. Over time, I have developed a few tips designed to increase your comfort level with the negotiation process and enable you to have reasonable expectations.

Tip #1. Do your research. You would not walk into an exam or new surgical procedure without preparing; you shouldn’t walk into negotiations without preparing either. Here are a few things to investigate before you discuss salary.

- Know what the regional starting salary is for your position and level of experience. The AAPA works hard to survey practicing PAs regarding their salary and benefits packages to create the AAPA Salary Report that is available free to AAPA members. (Remember this when the survey lands in your inbox next time – the more people that complete the survey, the more accurate the report is!) In addition to the Salary Report, I received helpful information by just asking classmates and colleagues with whom I have a good comfort level about their current salary range. It isn’t necessary to know the exact dollar amount, but a range of $10-12K was helpful to know if I was in the ballpark. Along with salary, you should also be asking about years of experience, hours worked per week, and other job demands. If you are applying for an outpatient family medicine position without night/weekend/call requirements – your friend in CT surgery who works 80hrs a week plus nights/weekend/call probably isn’t the best point of reference to start salary discussions.

- Know the range of benefits packages in your area. What are practices in your area offering for annual CME money? Do they cover your initial licensing costs or is there a delay? Some practices will only cover licensing and certification costs 6-12 months after start of employment, which means you may be responsible for those expenses. Remember, DEA fees alone are $750. Do they offer community perks like reduced-cost childcare, gym memberships, or subsidized parking/public transport passes? What do the short term/long term disability plans look like? Do you have employer matching for retirement plans? Do they offer a health reimbursement account? These aspects of a benefits package are easily overlooked but can save or cost you hundreds of dollars per year.

- Know the pay structure for the position. Are you salaried or hourly? This makes a huge difference when you continually work longer than scheduled. Hourly payment is becoming increasingly less common for PAs, but it still exists.

- Know the demands of the position. Will your job include nights, weekends, call? Are they compensated or part of the offered salary? Consider these demands in the context of your work-life balance as well.

Tip #2. Know your worth. What can you offer the employer in this position that others cannot? If you are a new graduate applying for a sports medicine orthopedic position and worked as an athletic trainer for 5 years before PA school – use that in your negotiations! Do you have an additional degree (MPH or MBA) that may help advance the practice? Don’t just expect them to add more money to the offer because you have more letters after your name. Discuss specifically how your prior experiences/degree could benefit your prospective employer.

Tip #3. Once you receive an offer, ask for time to consider your options. Accepting a job is a big decision. Most of us wouldn’t impulsively buy a house or make a large investment without taking some time to think about it. Consider accepting a job offer in the same way. Once you receive an offer, it is common to ask them for 48 hours to discuss this great opportunity with your family. Take the time to sleep on it, think about negotiations, and consider whether or not the job is a good fit for you.

Tip #4. Never, and I mean NEVER, take the first offer. This is a hard concept to teach people, especially new graduates and women. I have found that new grads are grateful for a paycheck and often jump at the first offer. Women, as seen in study after study, are much less comfortable with negotiating for themselves than their male counterparts. Interestingly enough, women are excellent negotiators on the behalf of others. I have discussed this concept with women I have helped with negotiating, and often times, changing their thinking from negotiating on their own behalf to negotiating on the behalf of their family (in other words, a better salary means more money for little Johnny’s college fund or Suzie’s braces) helps mitigate their discomfort.

Tip #5. Try thinking about salary talks in the long term, not the short term. You salary today could dictate your earning potential from here on out. Let’s say you take a job for $100,000 and annually you get a 3-5% cost of living raise (I’ll use 4% for the math). In year 2, you would be earning $104,000. Year 3 would be $108,160, etc. Now let’s say you negotiate a starting salary of $105,000. In year 2 you would be earning $109,200. Year 3 would be $113,563, etc. By year 5, you would be making nearly $6,000 more per year than if you didn’t negotiate at all.

Tip #6. Be prepared for the negotiation. You should craft a list of “wants/needs” and rank them in order of importance. This list is for your eyes only and will help keep you on track during negotiations. This list will likely change over time – I tend to see “Salary” on the top of most young negotiators’ lists and things like “Work-Life Balance” or “Retirement” on the top for more seasoned clinicians. A good starting point for talks may be the following statement: “Thank you for your generous offer…” then discuss some of the job/offer aspects that you liked, then you can state that “the base salary was a little lower than I was expecting, is there any room for negotiations?” And with that, the discussions begin. If they say yes, I recommend giving a range of expected salary and go from there. If they say no, you may ask if other aspect of the benefits package are negotiable such as vacation days, CME money, etc.

Tip #6. Be prepared for the negotiation. You should craft a list of “wants/needs” and rank them in order of importance. This list is for your eyes only and will help keep you on track during negotiations. This list will likely change over time – I tend to see “Salary” on the top of most young negotiators’ lists and things like “Work-Life Balance” or “Retirement” on the top for more seasoned clinicians. A good starting point for talks may be the following statement: “Thank you for your generous offer…” then discuss some of the job/offer aspects that you liked, then you can state that “the base salary was a little lower than I was expecting, is there any room for negotiations?” And with that, the discussions begin. If they say yes, I recommend giving a range of expected salary and go from there. If they say no, you may ask if other aspect of the benefits package are negotiable such as vacation days, CME money, etc.

Tip #7. Mentally prepare for all outcomes. No matter how good of a negotiator you are, sometimes the employer cannot meet your non-negotiable needs. It is at this point that you will have to reassess your needs or walk away from the position. Thinking about your limits prior to negotiations is paramount. After looking at your finances (rent, loan payments, insurance, car payment), what is the absolute lowest base salary for which you are able to work? Are you passionate about teaching students and this new job has a firm policy against taking students? Ultimately, the job may not be a good fit, which is OK. A polite conversation declining the offer with your reasoning will prevent you from burning bridges for future employment offers.

Tip #8. Be reasonable. Sometimes this is a tough conversation to have with new graduates. They heard about this PA in plastic surgery who makes $300,000 a year (totally possible, but obviously not the norm) and wants to negotiate something similar for him/herself. At the end of the day, salary is important, but it isn’t the only thing when considering a new job. Be sure to take all aspects into account and back up your salary and benefits requests with data – not just a one-off that you heard about through a friend of a friend.

I hope these basic tips will be helpful in your next negotiation. Comments with additional words of advice are always welcome!

March 22nd, 2016

The Art of Listening – Beyond Your Patient

Charity Maniates, MSPA, MPH, PA-C

In this situation, I could have discharged the patient home, attributed the patient’s dyspnea to just feeling tired, and simply had her follow-up with her PCP in one week. Realistically, the patient would have returned to the ED in 24 hours for rehospitalization. The therapist’s observations were key in my decision-making and ultimately led to a better outcome.

This scenario happens all too often. A multidisciplinary team member (e.g., a therapist, CNA) or a family member notes changes in a patient’s baseline that may be subtle or inconsistent. It can be easy to flippantly attribute such vague symptoms as self-limiting or irrelevant. However, a dismissive response to a team member’s or relative’s concern conveys that you prefer no communication and is degrading. That approach only causes breakdown and may delay needed early intervention or treatment for a patient.

This scenario happens all too often. A multidisciplinary team member (e.g., a therapist, CNA) or a family member notes changes in a patient’s baseline that may be subtle or inconsistent. It can be easy to flippantly attribute such vague symptoms as self-limiting or irrelevant. However, a dismissive response to a team member’s or relative’s concern conveys that you prefer no communication and is degrading. That approach only causes breakdown and may delay needed early intervention or treatment for a patient.

One busy morning, a physical therapy aide followed me to the nurses’ station and wanted to let me know that a patient seemed quite fatigued and unable to perform therapy. The 86-year-old patient had just been admitted to rehab a few days prior for generalized weakness after a fall resulting in a pelvic fracture. I remarked that it wouldn’t be out of the ordinary for her to be weak, but I sensed that the physical therapy aide was not satisfied. She showed me the patient’s vitals signs on a scrap of paper. “I know her vital signs are stable but I can hear her wheezing and she’s so weak.” This prompted me to see the patient that morning. The patient had diffuse rales and lower-extremity pitting edema, so I initiated diuretics and ordered a ProBNP (which was elevated) and an echocardiogram. Clinically, she improved substantially over the next few days and was ambulating with a walker. Because the physical therapy aide was persistent in her communication, treatment was initiated before the patient’s symptoms progressed. Early intervention in the elderly is essential, as decline happens swiftly and can lead to a transfer to the ED.

At end of life, those providing daily care are especially sensitive to subtle changes in patients’ breath sounds, respiratory rate, and overall responsiveness. These cues prompt shifting in medications or pain management or indicate that death is approaching. I was engaged in reviewing a long list of medications for a new patient when a CNA approached me. She was amazed that a hospice patient had been alert and talking the day before but had refused all her oral medications that morning and could not be roused. Normally, this report would be given to the nurse, but the one nurse on the unit was not available. My train of thought was derailed, and I had to shift my plan for the morning. I stopped by the patient’s room, and she was unresponsive with 10-20 second periods of apnea, indicating that death was close. She had declined further since early morning.

At end of life, those providing daily care are especially sensitive to subtle changes in patients’ breath sounds, respiratory rate, and overall responsiveness. These cues prompt shifting in medications or pain management or indicate that death is approaching. I was engaged in reviewing a long list of medications for a new patient when a CNA approached me. She was amazed that a hospice patient had been alert and talking the day before but had refused all her oral medications that morning and could not be roused. Normally, this report would be given to the nurse, but the one nurse on the unit was not available. My train of thought was derailed, and I had to shift my plan for the morning. I stopped by the patient’s room, and she was unresponsive with 10-20 second periods of apnea, indicating that death was close. She had declined further since early morning.

Due to the CNA’s report early in the day, I engaged in a meaningful interaction with the patient’s daughter regarding end-of-life care, and a clergy visit was initiated. It would have been impossible to orchestrate this if I had been paged in the middle of the night. My patient’s last 24 hours of life were comfortable, surrounded by family ushering her out of this world to another.

The hierarchy in medicine that results in devaluing of workers with less education is unprofessional and does not support a team-based culture. Healthcare systems need to empower multidisciplinary team members to vocalize concerns and validate their roles rather than diminish the work they do as menial and unimportant. Establishing rapport with these health professionals encourages them to feel comfortable approaching other providers. Being approached can be irritating when you’re attempting to return a page, writing an order, or reviewing a chart. But in my experience, the few extra minutes to stop and communicate can potentially change a patient’s course significantly.

March 16th, 2016

Drawing Meds: An Interview with Clinician-Artist Jorge Muniz, PA-C

Harrison Reed, PA-C

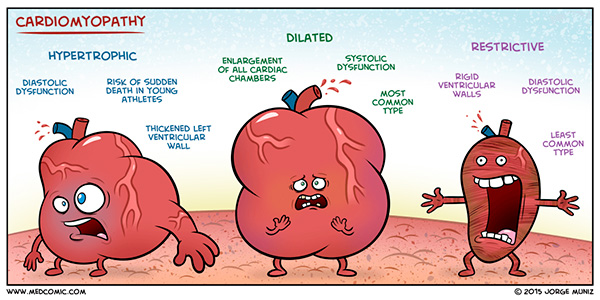

Muniz juggles full-time clinical practice with the skyrocketing popularity of Medcomic, but the balancing act is nothing new. After all, he started the comic series while attending PA school at Nova Southeastern University in Orlando, FL. But what started as a study diversion for his friends soon gained attention from university faculty and, eventually, students and educators around the world.

The cartoons themselves bear all the evidence of their creator’s DNA. Muniz grew up on a diet of Looney Toons and 1990’s Nickelodeon cartoons. And while his style reflects those animated roots, his work carries the undeniable compassion of his medical profession.

Muniz has parlayed the success of his Medcomic website into a book of the same name. The print project, financed by donations through a Kickstarter campaign, was released last year and has found its way to bookshelves as far away as Australia.

The talented clinician-artist spoke with me about the emotions of cartoons, connecting with fans, and how he — quite literally — puts his profession front and center.

HR: What cartoons did you grow up watching?

JM: When I was really little, I watched a lot of Looney Toons… I studied that. And in the ‘90s, when I was probably in middle school, I watched Ren and Stimpy (on Nickelodeon). And that’s probably one of my favorite art styles because they are very emotive. The material is kind of gross and stupid, but when you look at the art it’s really cool. The Looney Toons and the ‘90s Nickelodeon, Rocko’s Modern Life — things like that, I liked.

But those old Looney Toons, they don’t really make cartoons like that anymore…It’s gotten away from the cartoon acting, using the cartoon as a puppet to express your ideas. So if you look at my artwork, I think I try to incorporate motion into the drawing even though it’s a still picture.

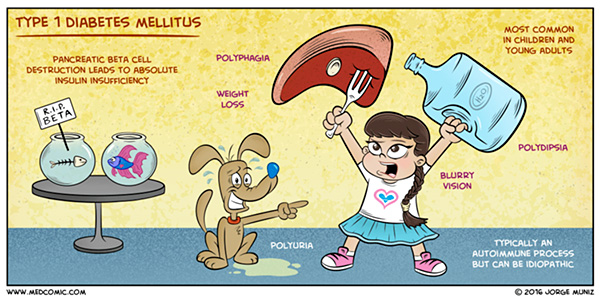

HR: Your cartoons are incredibly expressive and they have a ton of personality for things that are essentially inanimate objects. Do you ever base your cartoons on real people?

JM: Recently I drew a Type I diabetes cartoon and posted it (on Medcomic.com). It’s based off (my niece); she’s a young girl growing up with diabetes. So I drew that and dedicated it to her. And my whole family was really happy about seeing her depicted in a drawing.

The thing about drawing people in these cartoons is that there is a fine line between showing the disease process –and making it fun and fun to look at and humorous—and possibly going over the line and being offensive or making fun of the disease or the person that may have the disease. So I always try to keep that in mind and make it tasteful. But at the same time there’s ways to make it interesting and funny without poking fun. So it’s a balance and I think I walk that line pretty well for the most part.

HR: Did you ever think your artwork would turn into something that was successful in its own right?

JM: I’ve always wanted to achieve some success with my artwork because I’m so passionate about it. I never thought I would do a book. I was like, ‘I enjoy doing this and it’s helping people so I am going to keep posting this online.’ …And I was pretty consistent for the past two and a half, three years posting artwork. I think if you’re consistent with anything that you are passionate about, eventually you can achieve some success with it.

HR: You crossed a threshold with the Medcomic book, a project that was financed by a Kickstarter fund. You didn’t have any corporate overlords looking over your shoulder. How did that change the process of making a book?

JM: That was really important for me to maintain some creative freedom with the book. I did a lot of research before doing the Kickstarter, and I was concerned about that control, maybe a company taking the intellectual property of the drawings and then using it for other things. I guess I’m a little protective of the artwork and I wanted it to be for this purpose of, you know, helping students. So (self publication) let me maintain some control.

And it was a little nerve-wracking because I wasn’t sure if people would necessarily support that goal of making a book. I know people really liked seeing it online but a book is the next step. So, luckily it was successful and I got to make the book and I am really happy about that.

HR: A thousand years from now, future archeologists digging in central Florida only find one drawing. Which drawing do you want them to find?

JM: Oh man, that’s a tough one. You know, I think… I like… Hmm let me see…. Man that’s a hard question…. I like the cardiomyopathy one, I think.

HR: The drawings are kind of like your children. You have a really hard time picking between them. I can see the struggle on your face.

JM: (laughs) Yeah, hopefully they just dig up the book.

HR: What should our readers know about you and your work?

JM: One thing about the artwork is that I want to cover topics that people want to see. So I have a button up on the website for people to send requests. People may see the link and see the “Type Your Requests” and think that I don’t read it but I actually read every single email that comes through. And I appreciate everyone’s support. I get a lot of emails saying they really enjoy it, it helps. And I want to thank everyone and I do read the emails and take the suggestions into account — you know, what topics should be covered and things like that.

HR: So you’re a pretty accessible artist.

JM: I like interacting with people and hearing everyone’s thoughts.

HR: Do your patients know that you publish cartoons?

JM: Uh, no. But I think it might be cool to create some patient education materials with some artwork. One end that I haven’t really touched on is patient education… Maybe creating some pamphlets, or whatever the case may be, to get them to understand their conditions… Maybe it can help to create some materials that are more engaging.

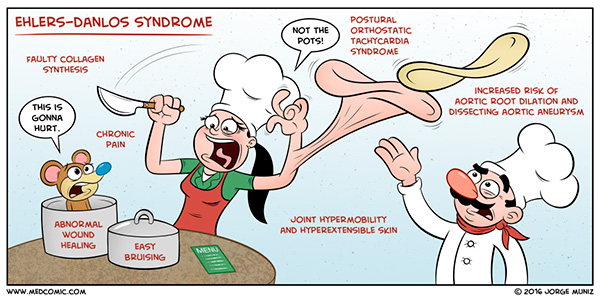

Actually, there was someone who emailed me and they had Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. And she wanted to say “Hey, I want to request this drawing, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, but I want to make sure that you include that this condition is very painful. We all live with this chronic pain, it’s very debilitating. And I feel like everyone thinks that it’s a stretchy-skin-disease but they forget this really affects our lives every day and it’s very painful. So that’s my request.” And I was like “OK, no problem.”

And I eventually did draw that cartoon and it’s up (on the website). And I wanted to get across that there was chronic pain in the drawing and I incorporated that. And then I got an email later and she was like “I love it!”

HR: There’s something very direct about the connection there. Emotion is kind of a central point in your drawings.

JM: Very emotional. Comic strips traditionally have to have a word bubble to express the idea. But a lot of the times (my work) is just the picture depicting the idea without any word bubbles. I try to make the image stand on its own. So you look at it, you get the picture.

I feel like it’s also cool because the PA profession seems to have this issue with being known in the media. In TV or movies, I feel like PAs are left out. If you create something that’s very accessible to a wide group, whether it be nurses, medical students, PA students, EMTs — and you have an international medical audience too — it kind of helps spread the PA profession in a positive way, too. I’m trying to make the PA profession a little more known. That’s why I put the “PA-C” on the front cover of my book. Some PAs might not have put the credential. I’m proud of the profession, so I want to put it out there.

Jorge Muniz currently lives and works in Kissimmee, FL. His work can be found at medcomic.com

March 10th, 2016

State Limits — Care Without Boundaries

Elizabeth Donahue, RN, MSN, NP-C

Despite the fact that Ellen and I have the same level of education and have passed the same national certification exam, Massachusetts has licensing restrictions that she is not subject to when her commute takes her 30 minutes in an opposite direction. While there are different licensing and regulatory statutes in many states across the country, those in Massachusetts are among the most outdated and restrictive. As had happened a number of times before, I was in the midst of a conversation that reminded me of how my home state’s restrictions limited my practice, as well as patients’ access to care. Normally I save chats about state politics for light cocktail party conversation, but since there are pending policy changes currently being considered by the Massachusetts legislature, it seems both timely and important to share both the facts about the regulations and my perspective as a person practicing in the current environment.

One of the current regulatory restrictions mandates that advanced practice nurses are subject to the oversight of both the state board of nursing and the state board of medicine, a model known as joint promulgation. Massachusetts is one of only a handful of states in the country that requires medical colleagues to oversee matters specific to the practice of APRNs.1 Massachusetts also currently mandates advanced practice nurses to enter into practice agreements with physicians deemed their “supervisors,” including retrospective review of the prescriptive practice of NPs. There are no data that suggest that these regulations are needed to ensure safe care. Nurse practitioner practice has undergone years of study, and outcomes and patient satisfaction data indicate equitable care.2

One of the current regulatory restrictions mandates that advanced practice nurses are subject to the oversight of both the state board of nursing and the state board of medicine, a model known as joint promulgation. Massachusetts is one of only a handful of states in the country that requires medical colleagues to oversee matters specific to the practice of APRNs.1 Massachusetts also currently mandates advanced practice nurses to enter into practice agreements with physicians deemed their “supervisors,” including retrospective review of the prescriptive practice of NPs. There are no data that suggest that these regulations are needed to ensure safe care. Nurse practitioner practice has undergone years of study, and outcomes and patient satisfaction data indicate equitable care.2

Evidence does exist, however, to suggest that loosening of these unnecessary regulatory restrictions will increase access to and quality of care for patients in Massachusetts as well as solve other issues facing health care at this critical juncture. The Institute of Medicine produced a report in 2010 entitled, The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health. The report recognized the size and potential scope of the nursing profession as assets in achieving the goals set forth by the Affordable Care Act, but also acknowledged that barriers existed; therefore, the number one recommendation of the IOM Committee that authored the report was that “nurses should practice to the full extent of their education and training.”3 Massachusetts is not immune to a shortage of access to primary care, with the majority of counties asking patients to wait more than a month for an appointment and most of Western Massachusetts with an average wait time upwards of 100 days.4 Finally, we are living in a time of escalating health care costs in which innovative practice models are being suggested to improve access and care while containing the ballooning costs of basic health care. Utilization of nurse practitioners as primary care providers, which was made legal in Massachusetts in 2008, has been studied as a possible cost savings measure as well. Studies have shown that states with less restrictions and more access have fewer emergency room visits and may produce lower prices in care and a cost savings to Medicare of up to twenty six percent.5,6

Given the preponderance of cost, safety and satisfaction data, it remains difficult to comprehend why there is opposition to this change in regulations. It is clear to me that my actual practice will not be affected — I will still carry my own licenses for practice and prescriptive authority, and ultimately my own liability for my clinical decisions. This regulatory change would reduce the administrative burden for physician colleagues currently being asked to supervise a practice that has already been shown to be safe and effective. My training has and will remain the same, I will continue to enjoy collaborating with my respected physician and nurse colleagues when I feel a clinical situation calls for it, but not because I am regulated to do so, because I care about my patients and their health. This is simply a change in language for Massachusetts that will position nurse practitioners to continue to care for patients in their communities without unnecessary burdens from a regulatory perspective. There are several national and local organizations that agree this would benefit patients, such as The Institute of Medicine, The Federal Trade Commission, and, most recently, the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission. When speaking about recommendations the Commission made at the Annual Cost Trends Hearing in October 2015, deputy director John Auerbach was quoted as saying: “here’s the bottom line: Massachusetts has among the most restrictive laws in the nation,” and he added that the laws were preventing patients from getting the care that they needed.7

Given the preponderance of cost, safety and satisfaction data, it remains difficult to comprehend why there is opposition to this change in regulations. It is clear to me that my actual practice will not be affected — I will still carry my own licenses for practice and prescriptive authority, and ultimately my own liability for my clinical decisions. This regulatory change would reduce the administrative burden for physician colleagues currently being asked to supervise a practice that has already been shown to be safe and effective. My training has and will remain the same, I will continue to enjoy collaborating with my respected physician and nurse colleagues when I feel a clinical situation calls for it, but not because I am regulated to do so, because I care about my patients and their health. This is simply a change in language for Massachusetts that will position nurse practitioners to continue to care for patients in their communities without unnecessary burdens from a regulatory perspective. There are several national and local organizations that agree this would benefit patients, such as The Institute of Medicine, The Federal Trade Commission, and, most recently, the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission. When speaking about recommendations the Commission made at the Annual Cost Trends Hearing in October 2015, deputy director John Auerbach was quoted as saying: “here’s the bottom line: Massachusetts has among the most restrictive laws in the nation,” and he added that the laws were preventing patients from getting the care that they needed.7

Ultimately, these proposed changes are not about my personal satisfaction as a clinician, or about Ellen’s commute. They are integral to ensuring that patients have access to and enjoy the benefits of high-quality health care wherever they live and from whichever licensed, qualified provider they choose.

- http://campaignforaction.org/resource/ma-action-coalition-report-advanced-practice-nurse-massachusetts

- Newhouse, Robin P. et al. “Advanced practice nurse outcomes 1990-2008: a systematic review.” Nursing Economics 29.5 (2011): 1-21.

- Institute of Medicine. (2010). The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. Retrieved from http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=12956&page=R1

- http://www.massmed.org/News-and-Publications/Research-and-Studies/2013-MMS-Physician-Workforce-Study/#.VOIG-tLF_84

- Traczynski, Jeffrey and Victoria Udalova. “Nurse Practitioner Independence, Health Care Utilization, and Health Outcomes.” Working paper, 2014. As of March 3, 2016: http://www2.hawaii.edu/~jtraczyn/paperdraft_050414_ASHE.pdf

- Perloff, Jennifer, Catherine M. DesRoches, and Peter Buerhaus. “Comparing the Cost of Care Provided to Medicare Beneficiaries Assigned to Primary Care Nurse Practitioners and Physicians.” Health Services Research, (2015): 6. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1475-6773.12425/abstract

- http://www.mcnpweb.org/news/news.asp?id=255697

March 2nd, 2016

Think Outside the Scale

Scott Cuyjet, RN, MSN, FNP-C

An 18-year-old female patient with a body-mass index (BMI) of 43 and no other health issues is referred for gastric sleeve surgery. She has tried multiple diets in conjunction with being moderately active and at best has paused or slowed her weight gain. Her parents and one sibling are not overweight, but her other sibling is. She is told she needs to lose 10% of her body weight over the next four months in order to qualify for the surgery, which seems to be a realistic goal based on this article from the Mayo Clinic. The patient weighs 260 pounds, so that makes 26 divided by four, which is 6.5 pounds a month or 1.625 pounds a week. The problem is that she has already tried multiple diets, is moderately active, and has still been gaining 10 to 30 pounds a year. When she returns for her pre-surgery appointment, she is chastised by the surgeon for not losing all of the weight. The surgeon states that it must be because she did not cut back on her already low 1100-calorie diet. The patient wants to say, “That is why I am resorting to this extreme as my last hope, you idiot,” but instead, tears just flow down her face. The surgeon says he will do the procedure anyway.

The problem my patient and I had with this case is that many healthcare providers are stuck in an antiquated metabolic model for weight gain, and patients are experiencing discrimination and harassment because of it. According to this model, any calories taken in that are not burned off by one’s basal metabolism or exercise are stored in one’s fat cells and weight is gained. Conversely, if you take in fewer calories than are used, your fat cells should get smaller and you should lose weight. This model does not explain how most of this patient’s adolescent friends can consume 3,000-4,000+ calories a day of junk food, often do very little activity, and still do not gain any weight. A critique of this model can be found in this article in Digg entitled, “The Calorie Is Broken.” As a provider dealing with overweight patients, I have been frustrated with the lack of data about why people gain weight if it is not because they eat too much and don’t exercise. I feel as though I have nothing to offer these patients to help them other than medications that are minimally effective with intolerable side effects, or surgery, which is extreme and has not been an option long enough to know about its potential long-term side effects. Ultimately though, people should not have to lose weight if it is not affecting their physical or mental health. I have patients who are overweight and have no negative health problems who are perfectly content with their weight.

The problem my patient and I had with this case is that many healthcare providers are stuck in an antiquated metabolic model for weight gain, and patients are experiencing discrimination and harassment because of it. According to this model, any calories taken in that are not burned off by one’s basal metabolism or exercise are stored in one’s fat cells and weight is gained. Conversely, if you take in fewer calories than are used, your fat cells should get smaller and you should lose weight. This model does not explain how most of this patient’s adolescent friends can consume 3,000-4,000+ calories a day of junk food, often do very little activity, and still do not gain any weight. A critique of this model can be found in this article in Digg entitled, “The Calorie Is Broken.” As a provider dealing with overweight patients, I have been frustrated with the lack of data about why people gain weight if it is not because they eat too much and don’t exercise. I feel as though I have nothing to offer these patients to help them other than medications that are minimally effective with intolerable side effects, or surgery, which is extreme and has not been an option long enough to know about its potential long-term side effects. Ultimately though, people should not have to lose weight if it is not affecting their physical or mental health. I have patients who are overweight and have no negative health problems who are perfectly content with their weight.

People who are obese have gained a majority of their stigma from data that suggest that the simple fact that someone is overweight or obese makes them unhealthy. The authors of the Digg article state, “[The] inability to curb the extraordinary prevalence of obesity costs the United States more than $147 billion in healthcare, as well as $4.3 billion in job absenteeism and yet more in lost productivity.” Lately there have been some emerging research studies that are questioning the theory that being overweight alone makes one unhealthy. In a recent UCLA study, researchers concluded that, “Close to half of Americans who are considered overweight by virtue of their BMIs (47.4 percent, or 34.4 million people) are healthy, as are 19.8 million who are considered obese.’” They also found that “More than 30 percent of those with BMIs in the normal range — about 20.7 million people — are actually unhealthy based on their other health data.” The health markers used in this study included blood pressure, glucose, cholesterol, and triglyceride levels.

As medical practitioners, we need to educate ourselves to think outside the box, or in this case, outside the scale, in regard to the causes of obesity versus the causes of hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and other markers of poor health. Other current obesity research points to gene-environment interactions as drivers of obesity — as in this article in the New England Journal of Medicine, which states: “There is good evidence indicating that although obesity may start as a lifestyle-driven problem, it can rapidly lead to disturbed energy-balance regulation as a result of impaired hypothalamic signaling, which leads to a higher body-weight set point. Thus, obesity may be considered a disease initiated by a complex interaction of genetics and the environment.” Some possible environmental culprits of this disruption include chemicals. A recent article in the New York Times Magazine about a chemical called PFOA highlights the dangers of such endocrine-disrupting chemicals that can “interfere with human reproduction and metabolism and cause cancer, thyroid problems and nervous-system disorders.”’ According to the same article, “There are 60,000 unregulated chemicals out there right now.”

Another theory among providers is that their overweight patients are just not moving enough. Yet according to this study in the journal Cell Biology (conducted in non-overweight/obese people), people with moderate activity levels only burned an average of 200 calories more a day than sedentary people did and that increasing exercise did not increase calories burned.

Yet another possible cause of obesity may be our gut bacteria. There are emerging theories and data about their possible effect on many health conditions including weight gain. As stated in an article in Scientific American, “New evidence indicates that gut bacteria alter the way we store fat, how we balance levels of glucose in the blood, and how we respond to hormones that make us feel hungry or full. The wrong mix of microbes, it seems, can help set the stage for obesity and diabetes from the moment of birth.” This article from the journal Open Forum Infectious Disease shows potential evidence for weight gain from a change in gut bacteria, although it is only a case study. It is a study of a 32-year-old woman who gained 34 pounds over 16 months after receiving a fecal transplant for C. difficile from her 16-year-old daughter, after which, “She had been unable to lose [the] weight despite a medically supervised liquid protein diet and exercise program.”

Finally, the biggest problem with not knowing more than we do is that the current explanations blame the patient. This can lead to discrimination and shame, which can negatively affect other aspects of patients’ lives. With regard to discrimination based on weight, this article in Psychology Today underscores that it comes from all directions, including healthcare providers. Its findings included:

- More than half of doctors described their overweight patients as ugly, awkward and non-compliant with treatment.

- Nearly one-quarter of nurses admitted to feeling repulsed by their obese patients.

- Nearly 30 percent of teachers said that becoming obese was “the worst thing that can happen to someone.”

- Defendants in lawsuits who are overweight are more likely to get slapped with a guilty verdict.

- More than 70 percent of obese people reported being ridiculed about their weight by a family member.

- Fifty-two percent of obese individuals believe they’ve been discriminated against when seeking employment or a promotion.

- Children as young as 4 are reluctant to make friends with an overweight child.

Other reports indicate that obese children are more likely to be bullied (although this article from CNN is from 2010, the information is still relevant), and obese adults (especially women) make less money than their average-weight peers.

With regard to my patient, it has been a little over a year and she has lost 50 pounds even though her diet and activity are similar to what they were before surgery. She now finds it easier and less stressful to buy clothes, has more friends, and feels more confident. So again, it cannot just be about calories. The removal of part of her stomach changed something about the way she is digesting food and storing or burning calories.

In closing, remember that just because someone is overweight does not mean they are unhealthy. We need to test all patients regardless of weight for things that are actually affecting their health. And remember to be kind and think “outside the scale,” as these are people with feelings who are being bombarded from many directions with messages both overt and subtle about their weight and body image.

February 24th, 2016

My Profession Made Me a Better Person

Bianca Belcher, MPH, PA-C

LESSON #1: Get personal perspective and keep it.

I’m not perfect. Just last week I had a small meltdown after the fax machine destroyed the only copy I had of a patient’s medical record from Japan. I can’t lie; I came close to pushing the entire machine down the stairs. We’ve all been there, but quickly regaining personal perspective is invaluable. Did the fax machine burn down my house, transmit a life threatening disease, or cause me permanent disability? No? Great, then 5-6 deep breaths should do the trick. This approach has been an enormous stress reliever in my day-to-day life.

LESSON #2: Share your perspective with your patients (friends, family), but don’t forget to get theirs.

We see patterns in our practices and in the literature that help shape our perspective on things, including outcomes. I use ruptured intracranial aneurysms as an example. Approximately 50% of patients with ruptured aneurysms die prior to getting to the hospital. Of the 50% who make it to the hospital, 30% die despite our best efforts, 30% are significantly impaired requiring assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs), 30% have mild impairments but can still complete ADLs independently, and about 10% are discharged at their pre-rupture baseline. If you are in the “mild impairment” or “pre-rupture baseline” groups, from my perspective, you are incredibly lucky — lucky enough to consider purchasing a lottery ticket on the drive home. From the patient’s perspective, those mild impairments are life-changing, and we providers should not be so quick to dismiss that. I had a patient with a significant subarachnoid hemorrhage secondary to aneurysm rupture who nearly died twice in house. Eventually she recovered beautifully. Her cognition and memory returned to baseline, but she had some residual right hand clumsiness and a 4/5 manual muscle test of her upper extremity. From our standpoint, she was basically perfect, but for her, life had changed dramatically. She loved to cook, but due to the clumsiness she was unable to use a kitchen knife with the same precision. Things were just different now for her. Although I couldn’t change her outcome, I could be better about listening to and integrating her perspective into the plan. This lesson translates easily into conversations with friends and family. Be mindful that the skills and characteristics that make you a great provider/alpha team leader (firm tone, direct, evidence-based decision-making, demanding, and work-driven) may not translate easily into your personal life. I have learned to be open to suggestions and to go with the flow once in a while. If I start twitching from lack of control and organization (consequence of “going with the flow”), I refer back to LESSON #1.

LESSON #3: Don’t be the Lamplighter

The Lamplighter is a character from The Little Prince, a children’s book written for grownups, by Antoine de Saint-Exupery. The Lamplighter lives on a tiny planet and lights a street lamp every night and puts it out in the morning. The catch is that the planet is so small that it has 1440 sunsets daily, which means the Lamplighter is rapidly lighting and extinguishing the lamp all day long so that the plants and people on the planet never go without light. For a period of time, I was constantly putting out work fires, staying late because stuff “needed” to get done, and never taking time for myself and my personal life. I was so obsessed with doing my job well for my colleagues and my patients that, much like the Lamplighter, I never took time to relax.

Take some YOU time. We talk about it. We even preach it. We just rarely do it. Make time to do things that you enjoy with people that you enjoy, and when you’re doing them, take a little extra time to appreciate the subtle things. You truly never know when it could all change. Our patients and their families say things like, “I wish I had known I was going to have a stroke because I would have taken that trip to Rome with my spouse” or “I wish I could have told them that I loved them one more time.”

Take some YOU time. We talk about it. We even preach it. We just rarely do it. Make time to do things that you enjoy with people that you enjoy, and when you’re doing them, take a little extra time to appreciate the subtle things. You truly never know when it could all change. Our patients and their families say things like, “I wish I had known I was going to have a stroke because I would have taken that trip to Rome with my spouse” or “I wish I could have told them that I loved them one more time.”

The work we do is important, but self-care is also important. Stop ending the calendar year with a bank full of vacation days. Use them. Go on a vacation. Sit on the couch and watch TV. Spend time with someone you love. It doesn’t really matter what you do – just take a break from the lamp lighting/extinguishing. I didn’t believe it until I tried it, but the hospital and our practice continued to run even when I took a vacation. I suspect yours will too.

I am a better person, and I have this profession and my patients to thank. I would love to hear lessons learned from other practicing PAs!

; [/php]/images/AU000_cmaniates.jpg)

; [/php]/images/AU000_hreed.jpg)

; [/php]/images/AU000_edonahue.jpg)

; [/php]/images/AU000_scuyjet.jpg)

; [/php]/images/AU000_bbelcher.jpg)