September 14th, 2016

Service Industry

Harrison Reed, PA-C

“You little clown,” A fleck of saliva flew from his mouth with each word. “Are you making a joke?”

The back of my neck grew hot as I sweltered under the man’s glare. He had arrived to the airport hours before his scheduled flight dragging his wife and three kids, depleted from a week at Disney World, through a mile-long trek of check-in lines and security checkpoints before finally arriving at the international departures terminal. But a 30-minute delay had stretched and multiplied and, as the sun dipped under the horizon, word arrived from the airport mechanics that the flight was cancelled. The airline offered consolation: a $15 meal voucher and an expanse of stained airport carpet on which to sleep.

“I can’t feed myself with this much less three kids…” the rant dissolved into a stream of profanity as his sunburned cheeks somehow glowed an even brighter shade of red. Behind him, 400 more passengers waited with similar sentiments.

Of course, the 17-year-old version of me who stood in front of that verbal firing squad had no control over flight cancellations or the value of food coupons. Wading through my first summer job at the airport, the only decision I really made was which soda to pick from the vending machine during my break. But looking back, I realize I was really only paid to do one thing in the high-octane service industry of air travel: to buffer that angry energy like a human shock absorber.

Of course, the 17-year-old version of me who stood in front of that verbal firing squad had no control over flight cancellations or the value of food coupons. Wading through my first summer job at the airport, the only decision I really made was which soda to pick from the vending machine during my break. But looking back, I realize I was really only paid to do one thing in the high-octane service industry of air travel: to buffer that angry energy like a human shock absorber.

Whether we like to admit it or not, healthcare is a service industry, too. And it always has been. After all, the revered small-town doctor who once made house calls with his little black bag was just providing a service. If something has changed since those days, it’s that our competition now includes self-diagnosis by Dr. Google, our ER wait times are advertised on billboards, and our app-powered society has turned patience from a virtue to a cardinal sin.

We see more patients with less time. Our fuses are half as long and burn twice as fast.

That means you don’t need to be a bad clinician to face your fair share of anger and resentment. An upset patient is not unlike those disgruntled passengers waiting in the airport: exhausted, frustrated, and in desperate need of good news. And while you hopefully don’t have a 747’s worth of patients outside of your office, the lesson might be the same.

We can’t rely on an extra pain medication refill or the not-so-indicated antibiotics to buy our patient’s happiness. That airport food voucher did little to appease my passengers. What they really wanted was for someone to stand at attention and listen.

I hear jokes about how the ER has turned into the Value Menu at McDonald’s or how survey-based reimbursement means primary care clinicians are now working for tips. I get the punch lines: we have transformed from scientist-artists to the customer complaint department, from steward to servant.

But maybe that’s not really the change we’re all feeling. Maybe the role is the same, but it’s just missing a key component. We’ve shifted from small businesses to hospital mega-systems. The communities we support have become larger, more complex, and more transient. Our priorities are determined in corporate boardrooms instead of at the bedside.

Maybe, all along, the only thing that separated us from other industries was the relationships we had with those we serve. And maybe, in our current system, those relationships no longer seem feasible.

I don’t have a quick fix for a healthcare system that seems to swallow the individual to feed the conglomerate. But I can focus on something smaller. If I face someone exhausted from his journey, frustrated by setbacks and looking for answers, I have two choices: I can ignore, deflect, or lash out at his emotion. Or I can be a small moment of relief in his otherwise savage world.

I chose medicine because I wanted to be like that small town doctor with his little black bag, the one everyone knew and trusted, like my grandfather I grew up hearing stories about. And maybe I don’t have those bonds forged over decades of dedicated care, but I’ve learned that isn’t the only definition of relationship. A relationship can start with a handshake at the exam room door, a word of encouragement when treatment fails, or a hug when all seems lost.

Those small gestures might sound trivial as millions of lives hang in the balance. But each one of us makes those tiny decisions all day long. And when they add up, it might be the only thing that separates a service industry from an industry that serves.

September 8th, 2016

Seasons of Healthcare

Elizabeth Donahue, RN, MSN, NP-C

Here in New England, the temperatures have started to dip in the evenings and the sun is setting earlier by the day. These changes are noted and commented upon during exchanges in coffee shops, the local market, and literally over the water cooler in my office. And this past weekend, my family, friends, and I sat on our local beach, soaking up what we all feared was the last of the summer sunshine (wearing a little less SPF than we would normally), and watching our neighbors haul their dinghies and kayaks home — all quietly acknowledging Labor Day as the end of summer.

While I welcome the season of “Pumpkin Everything” and look forward to pulling out my favorite sweaters (and putting my white pants and sandals in their respective places in the closet), I find myself thinking about what is to come in my work — how the changing of seasons affects primary care.

I’ve noted over the years that various conditions and complaints tend to occur in conjunction with particular seasons. So, as we say farewell to beach days and weekend trips to Cape Cod, in healthcare we are expecting a downturn in the number of visits and complaints centering around poison ivy exposures and tickborne illnesses. The calls coming in will be less and less likely to be related to injuries sustained while rock climbing and competing in office softball games.

I’ve noted over the years that various conditions and complaints tend to occur in conjunction with particular seasons. So, as we say farewell to beach days and weekend trips to Cape Cod, in healthcare we are expecting a downturn in the number of visits and complaints centering around poison ivy exposures and tickborne illnesses. The calls coming in will be less and less likely to be related to injuries sustained while rock climbing and competing in office softball games.

Instead, we have stocked up on flu vaccine supplies. We will start to triage calls about nasal congestion, fevers and sore throats. And soon after those calls peak, we will likely start examining patients with suspicion of rotator cuff and ligamentous knee injuries sustained while skiing and snowboarding.

Aside from these notable swings in urgent care issues based on outdoor temperatures and activities, there are even more subtle ways that the weather and season may have affected our patients. Some patients with diabetes or high blood pressure confess that summer is “harder” because it’s too hot to exercise or their weekends are full of outdoor barbecues, family reunions, etc. Others say they prefer it because foods are lighter and fresher (it’s easier to eat a salad in the summer than a large bowl of pasta), or because they have a pool where they can regularly swim for exercise.

We also have even more overt nods to the changing seasons in health care. We have an “allergy season,” a “cold and flu season,” and even “seasonal affective disorder.” We wear red in February to raise awareness about heart health, and October is widely known as Breast Cancer Awareness Month. (As an aside, when I looked these up on the internet to verify that I had my dates correct, I found several obscure designated health awareness days, weeks, and months that I’d never heard of, like “National Distracted Driving Awareness Month” and “World Sepsis Day”, including 45 acknowledged awareness events in the month of May alone.)

The change of season reminded me that healthcare is cyclical; by its nature, it is integrally tied to the cycles of life – bringing to mind the lyrics penned by Pete Seeger and made famous by The Byrds, all essentially plucked up from the Book of Ecclesiastes as they apply to our lives and our work in healthcare:

To everything (turn, turn, turn)

There is a season (turn, turn, turn)

And a time for every purpose, under heaven

August 31st, 2016

Why Men Shouldn’t Have to Do Pelvic Exams

Scott Cuyjet, RN, MSN, FNP-C

I want to be totally honest up front and say that my real motivation for this blog post is that I don’t want to do any gyn/vaginal exams. I am uncomfortable doing something so intimate on a patient. After the exam, we would both know I had looked at, touched, or been inside the patient’s vagina. It is not that I cannot do the exam: I have been trained, practiced on the professional gyn models, and practiced on some patients, but that was a long time ago, and like the medical student in this GomerBlog article, I have avoided it ever since. I am bringing it up now because due to a personnel change in our practice, I have been asked to consider performing vaginal exams. It would also be helpful if I were trained to insert and remove intrauterine devices.

I work with adolescents age 12-25 and I have seen — or projected — discomfort in their eyes and in their body language when I have brought up even the notion of future Pap smears or vaginal exams. Even if they are not uncomfortable, if I am, they will pick up on that, which may make them uncomfortable.

The current Pap recommendations are to start at 21 years of age and, if negative, repeat every 3 years until age 30, and then repeat every 5 years. Women also need pelvic exams if they have a growth in their genital area, a change in vaginal discharge, a change in smell emanating from the vagina, genital itching, painful intercourse or abdominal pain. Until now I have been able to defer this practice to a female provider in our clinic, but with the recent decrease in our providers, this may change. I and other males may be perfectly capable, but historically, and in other countries, it is an exam done by women such as midwives or female OB/GYNs.

The current Pap recommendations are to start at 21 years of age and, if negative, repeat every 3 years until age 30, and then repeat every 5 years. Women also need pelvic exams if they have a growth in their genital area, a change in vaginal discharge, a change in smell emanating from the vagina, genital itching, painful intercourse or abdominal pain. Until now I have been able to defer this practice to a female provider in our clinic, but with the recent decrease in our providers, this may change. I and other males may be perfectly capable, but historically, and in other countries, it is an exam done by women such as midwives or female OB/GYNs.

To avoid doing pelvic exams, I have had some patients do self-swabs, have switched patients with another provider, or have had patients come back to see a different provider. One of the reasons I feel I should not have to do these exams is that there are plenty of female providers (although some may be opposed to doing them as well). According to this article from the McGill Journal of Medicine, 58% of U.S. medical students are now women, up from 9% in the 1970s, and 72% of OB/GYN residents are women. That same article cites a study at one hospital showing that only 32% of high school students would accept an intimate examination by a medical student of either gender. In addition, 22% of clinic patients overall – and 55% of high school students — said they would accept only a female student.

Part of my apprehension is that, according to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center, 25% of girls will be sexually assaulted by their 18th birthday, and according to the Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network, 54% of sexual assault victims are between the ages of 18 and 35. I don’t want to remind patients of such trauma, even though the exam could be a positive experience through demonstration of consent and empathy. During my clinical rotations, I was overly gentle when doing pelvic exams specifically because I am a male and will never know what it is like to have one done on me. This is also mentioned in the McGill article when the authors state, “In fact, men might even have a heightened sensitivity about the distress that a gynecological exam can cause as they themselves have never undergone one. Something as routine as a Pap smear can be a really difficult experience for some women, and some men might go more out of their way to be gentle and explain what they’re doing than female gynecologists, who may feel it’s not that big of a deal because they’ve been through the process themselves.” That being said, I still don’t want to perform these exams.

Lastly, most of the women I know as patients and personally do not like having pelvic exams done, as they are awkward and uncomfortable.

August 25th, 2016

Travel Medicine: An Interview with Derek Hersey, MPAS, PA-C

Bianca Belcher, MPH, PA-C

Here’s an interview I did with Derek about his experiences in travel medicine…

BB: Tell me a little bit about how you got started in travel medicine?

DH: I was hired at Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates (HVMA) in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 2000, but it wasn’t until 2004 that PAs and NPs started to get involved in travel medicine appointments at the Cambridge practice. I started with 1 to 2 appointments per week and gradually expanded. In 2010, I was given the opportunity to pilot the Shared Medical Appointment (SMA) for Travel Medicine Program. SMAs would bring 5-10 patients together for a group visit. The concept of SMAs made sense because there were a number of subjects that were discussed with practically all patients traveling to any developing countries. SMAs were a very coordinated undertaking; at the time, we would have a dedicated nurse, medical assistant, scribe and a behaviorist who would act as a facilitator during the encounter. The visit would last approximately 90 minutes. They were well received, and I continued to do them until 2012.

In 2011, HVMA started a centralized travel medicine department as part of infectious disease. In 2012, I took on a part-time role in that department, continuing to split my time evenly between travel medicine and internal medicine. As time went on, the travel medicine group started seeing more and more consults for issues such as skin and soft tissue infections (MRSA), latent tuberculosis, complicated urinary tract infections, hepatitis B nonresponse, HIV PrEP, and recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. This trend led to me accepting a full-time position with the travel medicine department.

BB: Interesting stuff! What does a typical weekly schedule look like?

DH: As a department we have 4 advanced practice clinicians –3 PAs and 1 NP. The PAs and NP often practice at a different site each day, covering 13 sites. The schedules are very busy, seeing both adults and children, typically in 30-minute slots. We also see entire families in one extended appointment. As I said before, we also will see ID consults during the week focusing on the topics detailed above.

BB: Sounds like you really enjoy what you do. What is your favorite part about practicing in travel medicine/infectious disease?

DH: There are many enjoyable aspects about travel medicine. I enjoy preventative medicine and with my IM background have always been interested in infectious disease. I was intrigued by some of the diseases that we don’t see very often practicing here in the U.S., such as malaria, dengue fever, and chikungunya. After PA school I was able to do some international travel, which furthered my interest because I now had some context to apply to these conversations as well as experience to impart to my patients, not just information obtained by reading Travax or the CDC’s Yellow Book.

BB: I haven’t run into many other travel medicine PAs. Do you know of many other PAs doing this?

DH: I suspect that the number of PAs practicing in a specialty such as travel medicine is fairly small but hopefully growing. We have the opportunity to meet other PAs when we attend a conference or an event hosted by the International Society of Travel Medicine.

BB: ID was probably my least favorite class in PA school, but for a trip to Egypt I’d learn just about anything. Does working in travel medicine include actual travel abroad?

DH: Unfortunately, international travel is not part of the basic job description though many clinicians do take part in medical missions in developing countries, and many of the conferences hosted by the ISTM are located outside of the U.S. I would certainly like to take part in a medical mission in the near future. In 2010, one of my internal medicine PA colleagues and I were having serious discussions about traveling to Haiti during the cholera epidemic. Around that same time, there was a significant amount of violence and looting that took place up around Cap-Haïtien, where we had discussed flying into, and as a result aid flights from the U.S. and other countries were cancelled and we were unable to go. Another travel medicine PA colleague helped coordinate a medical mission to Haiti in November of 2014. When speaking to her recently, she touched on the subject of other PAs in travel medicine and remarked, “we certainly need travel/tropical medicine–trained clinicians here in the U.S. to prevent or recognize faraway pathogens that are making their way via global travel to our doorstep.”

BB: What are some of the other groups of clinicians with whom you work closely?

BB: What are some of the other groups of clinicians with whom you work closely?

DH: We collaborate certainly with internal medicine, family practice, and pediatrics. Generally, we try to collaborate with all specialties since it is not just young healthy people who want to travel. Quite often we will have patients with multiple comorbidities attempting to go on very adventurous trips. In these instances we may need to discuss patient care with our colleagues in endocrinology, cardiology or oncology, just to name a few. We also have a great relationship with our clinical pharmacy department. Our PharmDs are a great resource to us.

BB: What, if any, creative tools or techniques do you use for travel medicine appointments?

DH: We have created SmartSets in our electronic medical record that help with documentation as well as ordering tests and medications for our patients. We utilize a system called Travax that is an excellent resource and is updated on a daily basis, providing us with guidelines on what is recommended for patients traveling to any country in the world. The Travax packet we provide also includes yellow fever and malaria maps when the risk is present, illustrating to patients which regions of the country have high, moderate, negligible, or no risk of transmission. We review the patient’s itinerary in detail with them, discuss their past medical history, and review immunization records, medications, and allergies. We write prescriptions when indicated and almost always need to administer vaccinations. Detailed literature on various topics such as water and food-borne illness, insect precautions, as well as altitude sickness prevention is provided to the patient in their after visit summary. This document also includes their vaccination record. We also created an over-the-counter checklist for patients to use as a general guide when preparing for their trip.

We all try to give our patients tips and tricks along the way, such as securing their toothbrush to a bottle of water with a rubber band to continually reinforce the fact that they should not be using tap water to brush their teeth. When doing this, they are unable to grab their toothbrush without the bottle of water along with it. We also give patients starting the oral typhoid vaccination some literature detailing a reminder system for taking the 4 provided doses that need to be taken every other day. They can text the word “TRAVEL” on the day they start the vaccine series to the number provided by the manufacturer and they will receive a text every other day reminding them to take their final 3 doses.

BB: What has been your favorite trip abroad?

DH: That is a difficult question because every trip is so different. I think that my trip to Egypt in 2008 was probably my favorite. We sailed for 5 days down the Nile on a felucca sailboat. It is certainly a more basic way to travel down the Nile compared to the cruise ships that we saw passing us each day. We lived out of our backpacks, sailing during the day with our guide and visiting ancient temples along the way such as Kom Ombo and Edfu. We would pull to the bank at dusk and turn the felucca into an enclosed tent-like shelter and sleep there on the river bank overnight. We took a sleeper train from Cairo to Luxor, then sailed from Luxor to Aswan. Traveled south by convoy to Abu Simbel, then returned to Cairo by way of sleeper train. The trip took about 12 days and was a great experience.

BB: Sounds like an amazing trip. What are some of the most complicated areas in the world to travel based on viruses, parasites, the number of vaccinations needed, etc.?

DH: I would say that Africa is probably the most complicated region to visit considering the potential for so many different pathogens. A trip to a country such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo can involve vaccinations for yellow fever, hepatitis A/B, typhoid, meningitis, rabies pre-exposure prophylaxis, as well as a prescription antibiotic for travelers’ diarrhea (E. coli, salmonella, shigella, campylobacter). This is in addition to insect precautions to prevent dengue fever and chikungunya as well as antimalarial medication to be taken orally for the entire trip to prevent falciparum malaria. Other disease processes in this country include schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, cholera, tuberculosis, African trypanosomiasis, ebola and viral hemorrhagic fever. Finally, some people traveling to Africa also have the complicating factor of altitude, such as those wanting to climb Mt Kilimanjaro in Tanzania.

BB: I can attest to how much helpful information you give during appointments. What advice would you have for anyone interested in entering travel medicine?

DH: Travel medicine is a very interesting and fun specialty to work in. It is a growing niche for PAs either as a full-time specialty or combined with internal medicine or family practice. During these encounters we are able to sit down and talk with our patients about topics that are exciting to them. They are very upbeat and positive encounters. Working in travel medicine you get to learn so much about the many developing countries in the world, learn their geography, and discuss the issues that they as a country are trying to manage and combat on a daily basis. If ID and public health interest you, this is a specialty worth looking into. If you are a clinician already working in family medicine, internal medicine, or pediatrics, you probably have the opportunity to see patients who are traveling and can determine if it is something that you would enjoy doing.

BB: Derek, thank you so much for your time and expertise on the subject. I can bet you’ve enticed at least a few people to consider travel medicine in their future!

*Derek graduated from Alderson-Broaddus University in Philippi, West Virginia in 2000. Alderson-Broaddus University’s PA program, started in 1968, is one of the oldest in the country.

August 18th, 2016

The Caregiver Conundrum

Charity Maniates, MSPA, MPH, PA-C

My patient’s daughter, Jane, sits tensely on the edge of the wingback chair. Leaning forward slightly, her body, like a jack-in-the-box, stays seated, and she fires the question, “Do you really think my mother is ready to come home? Is this safe?”

Rippling beneath her intense body language and direct questioning is a pervasive fear that a catastrophe will occur if she brings her mother home. This anxiety swirls and lingers when families visit and observe loved ones struggling. My softly couched reply is concise: after a hip fracture, elders may have difficulty returning to their previous baseline. Embedded in this simplistic response are many variables impacting progress: comorbidities, dementia, fragility, and medications. Data show that elders with hip fractures experience increased infections and an increased risk of death within one year.

Jane’s 87-year-old mother, a woman with an indelible smile and sweet disposition, speaks only a few words and sentences due to advanced dementia. A few weeks earlier, a simple trip at home resulted in a hip fracture, a visit to the ED, and surgery. Although the hip repair was uneventful, pain impeded her progress. During rehab, it became apparent to her daughter that she requires assistance with transfers and ambulation and cannot be left alone, even for a few hours — a terrifying prospect for a caregiver overwhelmed with the emotional and financial responsibility of 24-hour care and work responsibilities.

Jane continues to talk, rapidly, as though the solution will unveil itself at some point in her thoughts. Although she has ample supports in place — an adult daycare program and home companions — she works full time and travels, and leaves her mother home alone for a few hours or overnight with an aunt who has mild dementia. Now, she will not be able to do this. I delicately probe, asking what is her most pressing concern. She leaps at the question and says, “I’m the only one to take care of her. What happens if I collapse and can’t do this? What will happen to her?” I don’t have a good answer. Nor am I able to offer any long-term resources she has not accessed aside from nursing home care.

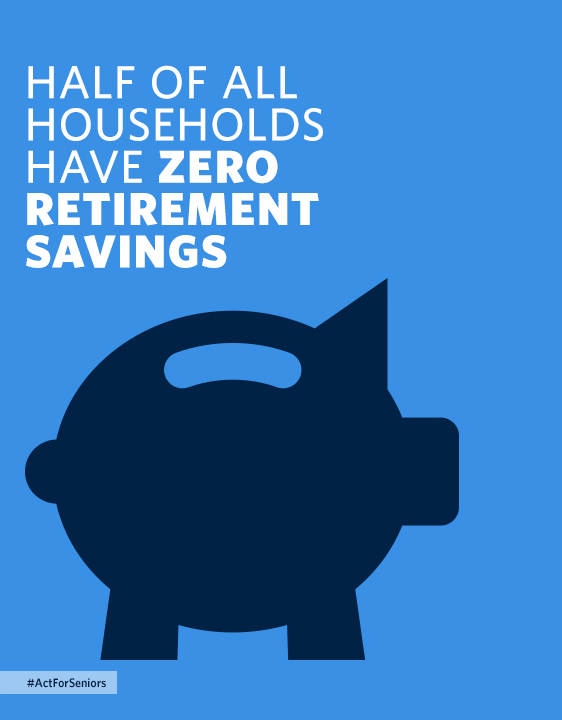

She is far from alone in her quandary. Of the massive cohort of 65+ adults that is growing exponentially, an estimated two-thirds will require long-term care (Kemper, Komisar, & Alecxih, 2005–2006), and nearly half will spend time in a nursing home (Spillman & Lubitz, 2002). Moreover, the average 65-year-old will spend $138,000 in future long-term-care service costs (Favreault & Dey, 2015), and those with dementia will incur substantially higher costs. Although nursing home care is primarily covered by Medicare and Medicaid, these massive structures must be bolstered through changes in policy and funding to sustain the growing demand for long-term care. For instance, legislation reintroduced in February of 2015 by Congresswoman Jan Schakowsky (D-IL) proposes increasing registered nurser (RN) coverage from the current federal mandate of only 8 hours daily to 24 hours/7 days a week. This would potentially improve quality of care, improve the ability to respond and assess patients, and allow for more personalized care that families and patients seek. If the act passes, nursing homes would receive Medicare and/or Medicaid reimbursement for the expanded RN coverage and would ultimately see improvement in quality care measures.

So, lacking a solution for her, I take a moment to validate her role as the primary caregiver and recognize how overwhelming it is. Pausing intentionally, I gently ask her if she’s ever considered an alternative such as long-term care. Inwardly, I cringe, wanting to offer a polished program or eco-friendly housing, rather than an institutionalized structure, to replace the personal care that a doting daughter has provided for years.

Her shoulders and head droop, and she can’t hold back the tears. “I feel so guilty! I told my mother she may not be able to stay at home, but that’s all she wants!” Guilt. A powerful driving force that keeps caregivers from placing a loved one in institutionalized care. And it’s quite understandable that caregivers have difficulty releasing their loved ones to a system trying to respond to the needs of the many, which cannot provide care with the caregiver’s intimate knowledge of a subtle tone of voice, a facial expression, or a favorite food. But the extensive tasks required to care for an elder with advancing dementia are taxing 365 days, year after year. Every aspect of care requires assistance: eating, drinking, toileting, dressing, and medication management. The tradition of elders living their last days in the family home is dwindling, and the only options are nursing home care and private care at home for those with financial resources. Both options can deplete a lifetime of savings quickly for the majority of working class families.

Our conversation starts to wind down, and she looks relieved that she vocalized her concerns and that I validated her deep-rooted fears. Taking a deep breath, she says, “Only time will tell if she improves, and I’ll go from there.” Grasping my hand tightly, she thanks me for talking. I smile, telling her that if her mother is not doing well at home, she should call the facility and her mother could return to skilled care. It’s the only short-term option I can offer her — providing a few extra days or weeks of care.

Turning to walk away, I glimpse her mother eating at the dining room table, and for a few minutes, I find solace in the fact that I was able to provide brief support to an overextended caregiver. The feeling is fleeting. I sigh sadly, knowing that Jane will be placing her mother inside the unfamiliar walls of a nursing home within a few months.

References

Favreault M, Dey J. Long-term services and supports for older Americans: Risks and financing. ASPE Research Brief. 2015.

Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, et al. Long-term care providers and services users in the United States: Data from the National Study of Long-Term Care Providers, 2013–2014. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 3(38). 2016.

Kemper P, Komisar HL, Alecxih L. Long-term care over an uncertain future: What can current retirees expect? Inquiry 42(4):335–50. 2005–2006.

Spillman BC, Lubitz J. New estimates of lifetime nursing home use: Have patterns of use changed? MedCare 40(10):965–75. 2002.

August 12th, 2016

Taking a Leap … Across the Pond

Megan Tetlow, PA-C

“Couch” not exam table, “theatre” not operating room, “obs” not vital signs: my first 2 weeks as a physician assistant practicing in England as part of the National Physician Associate Expansion Programme (NPAEP) have been exhilarating, enlightening, and more than a little disorienting. While I haven’t been in the UK long enough to speak with authority on the differences between our two healthcare systems, I have had a little time to reflect on the events that led a girl from sunny south Florida across an ocean to the heart of Yorkshire, England.

I first heard about the NPAEP last year on a Facebook post shared by the American Academy of Physician Assistants. It fortunately came at a time when I had been thinking a lot about what I wanted out of life, figuring out how to achieve it, and then just going for it. What I wanted was adventure … while continuing to work as a PA. The difficulty was that while the physician assistant model continues to expand, it remains a largely American profession. There are some opportunities for American PAs to practice internationally, but I found myself more limited as a PA that has always practiced in a specialty, specifically in gynecologic oncology.

Meanwhile, across the Big Pond, Dr. Nick Jenkins and the UK National Health Service (NHS) had developed a program to expand the role of physician assistants (here called physician associates) in England. The aim was to bring a group of American PAs to England for 2 years and place them in regions where there is a lack of practicing physician associates, in an effort to demonstrate to patients and providers alike the benefits that PAs could bring to the health system. The program wanted to recruit across different areas of medicine to demonstrate the breadth of midlevel provider abilities. As a result, and luckily for yours truly, they were recruiting among both generalist and specialty care providers.

Meanwhile, across the Big Pond, Dr. Nick Jenkins and the UK National Health Service (NHS) had developed a program to expand the role of physician assistants (here called physician associates) in England. The aim was to bring a group of American PAs to England for 2 years and place them in regions where there is a lack of practicing physician associates, in an effort to demonstrate to patients and providers alike the benefits that PAs could bring to the health system. The program wanted to recruit across different areas of medicine to demonstrate the breadth of midlevel provider abilities. As a result, and luckily for yours truly, they were recruiting among both generalist and specialty care providers.

I felt like I had stumbled upon my big chance. This was a rare opportunity to be able to live and work in another country, while continuing to work as a physician assistant. As an added bonus, and even beyond my original goals, I would be able to help foster the PA profession on a global scale and serve as a diplomat for a profession that I care so deeply about.

After applying and interviewing, to my surprise and delight, I was accepted into the program. Additionally, to my even greater delight, I found that I was to be placed with a physician group within my same subspecialty of gynecologic oncology. I knew it was just where I was supposed to be.

The time between then and our move in June has been a flurry of paperwork, visas, fingerprinting (four different times!), selling our worldly possessions, buying one-way plane tickets, more paperwork, and then suddenly and literally overnight becoming full-time foreigners.

Everyday, I learn a little more about our new home and new medical system. I look forward to sharing more about my experiences in the UK, to both highlight the differences and similarities between our two systems and how PAs fit into the NHS. Hopefully some of these insights will help us improve our own practice on either side of the pond. No matter what, one thing I know for certain is that these next 2 years are bound to be quite the adventure.

August 10th, 2016

Playing Victim

Harrison Reed, PA-C

America’s opioid epidemic is nothing less than a crisis. I could bury you under CDC statistics but I think the numbers have lost meaning. After all, the evidence is probably not far from where you are reading this right now. It is cold and hard and lying on a stretcher in the emergency department, in a cooler in the morgue, or in a nearby house sprawled on the bathroom floor.

And while that truth is harsh and tragic, we have compounded it with a second insult. We, a healthcare workforce of medical professionals, have decided to deflect blame and cast ourselves as the victims.

While researching the opioid epidemic for a recent editorial, I ran across the same narrative over and over again. Whether it is social media or popular blogs (or this Medscape post), the refrain is the same: they made us do this.

First, let’s get everyone on the same page. Opioid use, both illicit and prescribed, has skyrocketed over the past 15 years. Compelling evidence from the CDC suggests that many people currently addicted to illicit opioids like heroin began with prescription drugs, and a trend in increased prescriptions has coincided with an explosion in overdose deaths. This year, the CDC updated its recommendations to take a scientific stance on long-term opioid prescriptions: there is little to no compelling evidence of long-term efficacy and a plethora of proof of significant harm.

First, let’s get everyone on the same page. Opioid use, both illicit and prescribed, has skyrocketed over the past 15 years. Compelling evidence from the CDC suggests that many people currently addicted to illicit opioids like heroin began with prescription drugs, and a trend in increased prescriptions has coincided with an explosion in overdose deaths. This year, the CDC updated its recommendations to take a scientific stance on long-term opioid prescriptions: there is little to no compelling evidence of long-term efficacy and a plethora of proof of significant harm.

Now the waters get murky. Many clinicians will protest that they are subject to much larger forces driving the opioid prescribing epidemic. The general explanation goes like this: federal mandates from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have linked reimbursement for healthcare services to specific scores and standards. To evaluate these standards, CMS employs companies like Press Ganey—in what has become a multibillion-dollar industry—to survey patients about their experiences. Among other topics, these surveys place a high emphasis on pain. After all, the Joint Commission told us this was the “fifth vital sign,” right?

Facing financial and administrative pressures, time and resource-crunched clinicians have had no choice but to appease the growing demand for pain control with the use of opioid drugs. The expectation of the patient is to be pain-free, and the expectation of the payer and the employer is a satisfied patient. The prescriber is merely surviving in an environment that has him practicing with a proverbial gun to his head.

Sound familiar?

I don’t dispute this logic or the truth it holds. There are major forces at work in our industry that make doing the right thing very difficult. But if we hide behind that shield, or worse, use it to absolve ourselves of all blame, then we are confessing to a voluntary violation of our deepest principles.

We made no promises to pharmaceutical companies. We swore no allegiance to Press Ganey or survey scores. We pledged nothing to financial viability or industry business models.

But every physician and PA stood in a room somewhere, in front of mentors and peers and family, and took an oath to above all else protect our patients, to do them no harm. When we prioritize financial reimbursement or job security, we betray the purpose we were meant to serve.

There is plenty of blame to share with others, and the easiest choice is to point fingers, change the subject, and carry on. But let the other parties scramble for moral cover. Let the Joint Commission renounce the fifth vital sign and let those who have never held a crying widow obsess over arbitrary performance measures. We need not do the same.

We are highly educated, financially secure, outspoken professionals. We can do more than complain about patient surveys. We can do more than moan about the injustices of a system that has brought us so many rewards. We can stand for something bigger than the self-interest that others rush to protect.

But first, we need to stop playing victim.

There are real victims in this tragedy. They are the patients with chronic pain who think narcotic dependence is the pinnacle of medical care. Or they are in comas from which they will never wake. Or they died alone. Or they buried their children.

We can play a different role. We can become leaders for a solution. We can change our prescribing culture. We can open a dialogue with hospital leaders. We can contact our government representatives and force them to listen.

But as long as we deny our part in the problem, we won’t be able to embrace our role in the solution. And in this epidemic, that denial is lethal.

July 27th, 2016

School Schedules Make for Sleepy Teens

Scott Cuyjet, RN, MSN, FNP-C

As a parent of teenagers, I am reminded of that statistic every night as I try to get them to sleep at a reasonable hour, and every morning, as much as I struggle to get up, it is much worse for my 15- and 16-year-olds. Every day I have to cajole and sometimes force them to get up and get ready. They slowly move through their morning routine like zombies as I remind them of things they need to do to get ready.

These research findings are also relevant to my job as a nurse practitioner, as most of my patients are high-school-age. This is one of the reasons our clinic opted to open at 9:30 a.m. at its inception 25 years ago. At that time, our founders were aware of the data supporting the importance of sleep for adolescents. Some of the documented health deficits associated with lack of sleep include being overweight, alcohol and substance use, smoking, and poor academic performance.

Today, there are many barriers to adolescents getting enough sleep. One of them is the use of electronic devices like cell phones, tablets, eReaders, and laptops, which are often used right before going to sleep. In a 2014 paper, sleep researchers documented disrupted Circadian rhythms in people using light-emitting e-readers before bedtime and noted the particular challenges for children and adolescents, “who already experience significant sleep loss.” The authors called for further epidemiological research evaluating the long-term health and safety consequences of e-readers. (My mom, a librarian, would argue that this is a reason to go back to paper books, at least before bed.)

Another source of sleep deprivation, according to my adolescent patients, is the amount of homework they have on top of other activities. In one recent article, students report spending a nightly average of over three hours on homework. Many students don’t even get to start homework until later in the evening given their after-school activities.  A recommendation by one national homework expert cited in that article is: “multiplying the student’s grade level by 10 to get the optimal amount of time that should be spent on homework each night; this means that freshmen in high school should spend no more than 90 minutes and seniors no more than 120 minutes on homework each school night.” Granted, this recommendation can only be implemented with buy-in and participation from teachers.

A recommendation by one national homework expert cited in that article is: “multiplying the student’s grade level by 10 to get the optimal amount of time that should be spent on homework each night; this means that freshmen in high school should spend no more than 90 minutes and seniors no more than 120 minutes on homework each school night.” Granted, this recommendation can only be implemented with buy-in and participation from teachers.

In response to this issue, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that middle and high schools should start at 8:30 a.m. or later to allow students the opportunity to get the recommended amount of sleep on school nights (about 8.5–9.5 hours). In my own experience, I would say that 9:00 or 9:30 a.m. would be even better start times, although I recognize that getting kids to school at that time might be difficult for parents whose work day starts before then.

July 20th, 2016

The Fringe: Part 4 – Retirement

Bianca Belcher, MPH, PA-C

Here is a brief Q&A on the basics:

What are a 401(k) and a 403(b)?

Depending on your choice of employment, chances are you will have the opportunity to participate in your company’s 401(k) or 403(b) plan. The “401” and “403” simply refer to the section of IRS tax code that they come from – 401 is for private companies and 403 is for non-profit employers. These plans are designed so that you, the employee, can defer a portion of your salary prior to paying taxes (tax deferred) into these savings devices. Once you put money in a 401(k) or 403(b), your money will grow based on the investments that you select until you reach retirement age.  You may access the money in these accounts without penalty once you have reached the age of 59.5. Any money that you do take out of these accounts, presumably in retirement, will be taxed at your then individual tax rate. These plans currently (as of 2016) allow you to contribute up to $18,000/year if you are under the age of 50. That limit tends to change periodically based on inflation, so be aware if it increases and you are able to put more into these accounts.

You may access the money in these accounts without penalty once you have reached the age of 59.5. Any money that you do take out of these accounts, presumably in retirement, will be taxed at your then individual tax rate. These plans currently (as of 2016) allow you to contribute up to $18,000/year if you are under the age of 50. That limit tends to change periodically based on inflation, so be aware if it increases and you are able to put more into these accounts.

What is a Roth IRA?

A newer savings vehicle is what is known as a ROTH IRA or a ROTH 401(k). As it relates to you, the employee, the biggest difference between a ROTH and a regular 401(k) or 403(b) is that ROTH contributions are made after taxes, meaning that you will have already paid income tax on these contributions as you put them in. Naturally, that means that you do not have to pay income tax on those contributions when you take them out. In addition, withdrawals can be made before age 59.5, with the caveat that any growth made on those contributions must remain in the account until after that age. The downside of the ROTH option is that there are current limits placed on who can contribute to these accounts based on income levels. These levels change periodically, but at the time of this article, you can fully contribute to a ROTH IRA if you make $116,000 or less, with phased-out (limited) contributions allowed up to $131,000. After $131,000, you become ineligible to contribute to a ROTH. For married couples, you may fully contribute if you make less than $183,000 (household), making phased-out (limited) contributions up to $193,000. If you make more than those limits, you may not participate in a ROTH account.

How do you estimate how much you should contribute to your retirement?

How do you estimate how much you should contribute to your retirement?

People always ask how much they should contribute to their retirement account, and the answer is: It depends! A common answer is as much as you can as early as you can, but what does that look like? This is where budgeting and putting together a comprehensive financial plan really help. As stated in The Fringe: Part 3 – Deciphering Your Benefits Package, you should make sure that you are at least putting in what your company will match. Beyond that, it becomes a budget decision based on what else you have to pay for in your life. Try to pay your future self first, but everyone knows that life costs money, and we can’t all max out our annual contributions at $18,000, at least not yet. Many say 10% is a good start, but look at your own financial situation and make the decision best for you. Look at your salary, do the math, and contribute as much as you can at the time. Many people will take their annual pay increase and just simply increase their contributions each year. Another hint is to decide on your contribution amount at the start of your job so that deductions start on your first paycheck. It’s a bit of a silly mind game, but you don’t miss what you didn’t have to begin with! It is always hard to go in several months later and give up 10% of your check.

I hope that this series of posts,”The Fringe,” was helpful. A special thanks again to Highland Financial Group for their content expertise and support during this series.

; [/php]/images/AU000_bbelcher.jpg)