February 10th, 2016

What Did You Expect?

Harrison Reed, PA-C

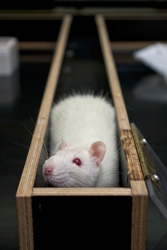

The rats all came from the same scientific supply company and, as far as Rosenthal knew, all were of average intelligence. Rosenthal handed the animals to unsuspecting researchers with the false notion that some were exemplary while others were far below average. When the researchers ran their rodents through a challenge of mazes, the animals believed to be extraordinarily intelligent performed far better than their mislabeled peers. It appeared the mere expectation of each rat affected its performance.

Rosenthal would later demonstrate the same now-famous results in humans when he misled schoolteachers into thinking some of their students were burgeoning geniuses. The students of which more was expected showed far greater gains in IQ tests than their classmates. This notion that expectation could alter function was later called the Pygmalion effect.

Rosenthal would later demonstrate the same now-famous results in humans when he misled schoolteachers into thinking some of their students were burgeoning geniuses. The students of which more was expected showed far greater gains in IQ tests than their classmates. This notion that expectation could alter function was later called the Pygmalion effect.

The power of expectation has been replicated again and again but the implication of this knowledge, especially in healthcare, has made little practical impact. And it’s hard to imagine why.

After all, the practice of medicine revolves around setting expectations. Don’t our patients always want to know the time-to-onset, the duration of treatment, the prognosis? If expectations have as much power as Rosenthal asserts, why haven’t we influenced expectations as much as we manipulate outcomes?

The very idea opens a vast frontier of possibility. Maybe patients would be more compliant with treatment. Maybe hospitals could reduce readmissions. Maybe that septic patient in the ICU would turn the corner. Maybe we should just expect it.

Of course, it can’t be that easy. The cascade of inflammation in sepsis is far more complicated than a cardboard maze. And no one thinks we should replace medicine with wishful thinking. You can’t prescribe Pygmalion.

But then again, no one willed the rats in those mazes to outperform. The million imperceptible factors that boosted their abilities were the result of intricate deception. The duped researchers and schoolteachers didn’t want an improvement, they just believed in one. It wasn’t the rats or the children that changed, it was their environments.

How do we capture something so evasive, a power that by its very nature requires the user to be unaware of its effect? Perhaps we are not intended to rein in this part of human psychology. It might be enough to appreciate just how much our subconscious affects our environment. If Rosenthal is right, the currents of expectation already swirl around us. It is our burden to decide if they are productive or destructive.

So the next time a patient or coworker teeters on the razor’s edge between success and failure, and some subtle force seems to nudge them toward an ultimate outcome, ask yourself one question.

What did you expect?

February 3rd, 2016

Back to Basics – What the Patient Can Tell Us

Elizabeth Donahue, RN, MSN, NP-C

This was my sixth trip to Haiti, spending a little over a week in the city of Leogane and surrounding villages. It’s an area a few miles west of the capital city of Port Au Prince, bordering Carrefour, the site of the epicenter of the earthquake that shook the country’s foundation in January of 2010. During our time in Haiti, our main focus is running daily mobile outpatient clinics – this year a team of 25 nurse practitioners, nurses and students from the Boston College Connell School of Nursing provided care to just shy of twelve hundred patients.

In a profession where there are not always clear and concise answers (which I enjoy immensely, having a background in research and likely having worked on one too many regression analyses), I tend to find comfort in clinical settings among data. Here at home in the U.S., I have many tools that produce numbers that I can then use to assist in decision making: How much movement can I get on a patient’s A1c by adding one type of medication versus another? What was the most recent PHQ 9 score in this depressed patient? What did the sleep study show?

But each year, it is the work I do and witness in Haiti that reminds me that the numbers and data are just one piece of this very big clinical puzzle. The numbers are helpful tools, but they shouldn’t be the first ones we reach for and they often aren’t the source of the most important information – that comes from the patient themselves, either verbally or on exam.

On one of our first trips to Haiti, I remember a colleague caring for a patient with a high blood pressure – about 230/110 – not uncommon in Haiti though enough to make any provider start sweating. She looked at me and another NP and said – “where’s the EKG machine?” and my colleague who has made over 25 such trips broke into a wide grin, shaking her head in a “no” motion. She held her stethoscope above her head and replied “this is it.” The truth is that we won’t ever know if the patient has an old infarct or possible LVH. But after taking a very good history, performing a thorough assessment, and if possible repeating the evaluation in a brief and reasonable follow-up period, we can likely make the appropriate recommendations for management.

It can be hard to remember the power of a good history or a complete and thorough exam when we are used to the tools and technology that are constantly at our disposal in a well-funded clinical setting while caring for a well-insured patient. It can be even more difficult to resist using them when the patient is aware of them and is requesting these tests. Or worse, when we fear litigious repercussions. And there are certainly instances where their use is not only appropriate but essential. However, after spending two weeks caring for patients without a CT scan, ultrasound, or endoscopy, I am settling back into the idea that I should be careful and deliberate about the use of diagnostics and spend more time listening to both what the patient and the body has to say.

January 20th, 2016

4 Indirect Ways Outpatient PAs Can Contribute to Practice Growth

Bianca Belcher, MPH, PA-C

- Clinical Feedback to Referring Providers

In my practice, this has probably been the highest-impact indirect way that I have contributed to practice growth. In our urgent surgical service we receive patients from a wide range of referral sources (varying by geography, specialty, and time of day). Every patient who is referred to us from an outside institution receives either a phone call or an email within 48 hours thanking them directly for the referral and updating them on the patient’s status. Many patients who are referred to us come from outside emergency departments or EMS and once the patient is transferred, these providers often have no idea of the outcome. We send an email with before and after imaging as well as a case synopsis and outcome (good or bad). We include our direct contact information in case these providers have follow-up questions. These emails contain high-level/complex medical information that could not be duplicated by a non-clinician such as an administrative assistant (AA). This peer-to-peer contact has been invaluable in opening up important patient care dialogue as well as developing a steady stream of new referrals.

TIP: In the beginning we had difficulty tracking down specific ED providers at hospitals outside of our EMR system. Often times transfer paperwork that came with the patient was not scanned in a timely fashion. In order to circumvent this problem, we began sending our feedback emails to the ED Chief of the transferring hospital and asking him/her to forward the email to the direct care team involved, including MDs, mid-levels, nurses. This allowed the email to reach the entire team (not just the attending) as well as department leadership.

- Lectures/Presentations

There are several opportunities to provide community education and awareness of your practice through lectures and presentations. All clinicians within our division are expected to give lectures. As a group, we aim for an average of 2 lectures per month or 24 lectures per year, which helps get our names and faces out in the community. A sample of our target audiences includes:

- Community/Non-urgent referral sources: Primary care and neurology practices

- Urgent referral sources: Emergency departments and EMS

- Neurology nurses: Spending a short amount of time educating nurses on how to best take care of their patients goes a long way towards improved patient safety and mutual professional appreciation.

- Understanding Billing at your Institution and in your Specialty

I do realize that this is easier said than done in some institutions, but I do feel strongly that a good understanding of what services are billable — for both you and the physician(s) with whom you work closely — can change practice revenue dramatically. For example, in my practice, we were all very familiar with the surgical global period of 90 days, the duration of time in which we could not bill for services related to our operation. However, we did not know that most neurological endovascular procedures do not have a global period. In fact, only endovascular carotid stenting procedures have a global period, which means that we are able to bill subsequent hospital visits and clinic follow-up on diagnostic angiograms, embolizations, thrombectomies, etc. In this example, our day-to-day patient care did not change, but we are now reimbursed for work we were already doing.

- Analyzing your Current Practice for Inefficiencies

PAs are in a unique position within many medical practices because we are one of the few people who interact with patients from A to Z. In an outpatient practice, a PA may be involved in everything from clinic setup/prep to surgery and postoperative recovery. AAs are heavily involved on the front of scheduling/insurance preauthorization and then again on the back end of scheduling post-op/follow-up clinic appointments. Unfortunately, they aren’t privy to much in between. On the other hand, physicians are typically involved in complex medical management or the surgical procedure, but not much before or after. PAs see it all. Use this distinctive point of view to identify practice inefficiencies, offer solutions, and oversee the implementation. An example of this was educating our AAs on common surgical procedures, their predicted length of stay, and typical postoperative follow-up time. After educating them and developing a cheat sheet, if they saw a booking for a common surgical procedure, they were able to predict that patient’s length of stay, set up their postoperative appointment, and send the patient a packet containing all appointments — all prior to surgery. This helped decrease phone calls to the office from rehabs and patients trying to set up postoperative appointments.

PAs are in a unique position within many medical practices because we are one of the few people who interact with patients from A to Z. In an outpatient practice, a PA may be involved in everything from clinic setup/prep to surgery and postoperative recovery. AAs are heavily involved on the front of scheduling/insurance preauthorization and then again on the back end of scheduling post-op/follow-up clinic appointments. Unfortunately, they aren’t privy to much in between. On the other hand, physicians are typically involved in complex medical management or the surgical procedure, but not much before or after. PAs see it all. Use this distinctive point of view to identify practice inefficiencies, offer solutions, and oversee the implementation. An example of this was educating our AAs on common surgical procedures, their predicted length of stay, and typical postoperative follow-up time. After educating them and developing a cheat sheet, if they saw a booking for a common surgical procedure, they were able to predict that patient’s length of stay, set up their postoperative appointment, and send the patient a packet containing all appointments — all prior to surgery. This helped decrease phone calls to the office from rehabs and patients trying to set up postoperative appointments.

I know there are several PAs out there contributing to practice growth and the business development of medicine who have been doing so for years. Do you have any other suggestions for new graduates or experienced PAs just looking to get more involved in the non-clinical aspects of medicine?

January 13th, 2016

Off to the Races — Maximizing the PA Role to Fill Healthcare Gaps

Charity Maniates, MSPA, MPH, PA-C

Eventually, my path lead me to train as a physician assistant, currently touted as one of the top 10 promising career choices by Forbes, Time, and The New York Times. That’s quite an accolade for a fairly young medical career (the first graduating class was in 1960). Yes, job growth, salary, position availability, and training are usually the major factors in these ratings, but there’s more to it than that. Entrance into PA school is competitive and selective; applicants must have diversity of experience and well-developed communication skills and must demonstrate strong teamwork and resilience. PA training is generalized, providing exposure to many areas of medicine, underscoring the versatility and lateral movement of the PA role. Growing voids in primary care both in underserved urban and rural communities are requiring many PAs and NPs to fill the PCP role, maximizing our scope of practice. PAs are first assists in surgery and integrated in acute, subacute and general medicine in outpatient and inpatient settings. In a primary care setting, PAs can accomplish 85% of a physician’s workload at one-half the salary. And of course, the cost of graduate education is significantly less than going to medical school. Utilizing PAs is a cost-saving approach to increasing access to care, reducing hospitalizations, and improving the quality of healthcare. No wonder there has been an exponential growth of PAs in the last five years. We are needed desperately.

Eventually, my path lead me to train as a physician assistant, currently touted as one of the top 10 promising career choices by Forbes, Time, and The New York Times. That’s quite an accolade for a fairly young medical career (the first graduating class was in 1960). Yes, job growth, salary, position availability, and training are usually the major factors in these ratings, but there’s more to it than that. Entrance into PA school is competitive and selective; applicants must have diversity of experience and well-developed communication skills and must demonstrate strong teamwork and resilience. PA training is generalized, providing exposure to many areas of medicine, underscoring the versatility and lateral movement of the PA role. Growing voids in primary care both in underserved urban and rural communities are requiring many PAs and NPs to fill the PCP role, maximizing our scope of practice. PAs are first assists in surgery and integrated in acute, subacute and general medicine in outpatient and inpatient settings. In a primary care setting, PAs can accomplish 85% of a physician’s workload at one-half the salary. And of course, the cost of graduate education is significantly less than going to medical school. Utilizing PAs is a cost-saving approach to increasing access to care, reducing hospitalizations, and improving the quality of healthcare. No wonder there has been an exponential growth of PAs in the last five years. We are needed desperately.

If you are a physician assistant, you know all of this. Our training mirrors the medical model to enhance our collaborative role with physicians. Now that I am a practicing provider in subacute and longterm care, I appreciate the effectiveness of team-based patient care. With the passage of the Affordable Care Act, PAs have been elevated in the national spotlight as the key solution to meeting primary care shortages. This can also extend to primary care needs in the longterm care setting as well. Although it’s an undertaking, PAs have been trained to meet the challenge, but dysfunctional systems need to be improved to ensure success. With the development of medical home models and emphasis on team-centered healthcare, hopefully PAs and NPs embracing the PCP role will be less burdened. Yet, antiquated state and federal restrictions still exist that limit PAs’ scope of practice in prescribing specific medications, ordering home health services, and providing hospice referrals. In addition, Medicare reimbursement rates are lower for PAs providing the same level of care of physicians. This seems counterproductive and clashes with the expectation of healthcare reform. Since PAs are able to provide a level of primary care that is on par with physicians, the misconception that a PA is merely a “helper” is severely outdated. It’s essential that PAs practice at full capacity of our licensing to ensure quality patient care and meet the healthcare needs in our communities.

I didn’t know as a girl that I would stumble upon a career that is almost as exciting as racing horses on Churchill Downs. I’m content to relive that girlhood dream on television every year, while the real action happens day to day caring for patients.

January 6th, 2016

Good, Then Fast

Harrison Reed, PA-C

And I hate to hear it. I hate that, as the years go by, it’s a concept that seems to grow in popularity. I hate that the people saying it have been working much longer than me. I should respect them; they should be wiser. I hate what it says about our industry. I hate what it means for our future.

I hate it.

Now this is the part where you tell me that I don’t understand because I am too young, too inexperienced. Of course, I should shy away from fast. I’m the new guy trying to tackle my second specialty in three years. Maybe I’m just rationalizing my own plodding pace. After all, I’m the writer who told you I was fresh off the zebra farm, right?

But I understand the origins of the “better fast than good” mentality. I’ve seen the crowded emergency departments and the packed ICUs. I know how long people wait for a primary care appointment or a specialist referral. I raged at delays while my own mother searched for a diagnosis.

In medicine, time is everything. But at some point we focused more on saving time rather than how we spend it. We became so obsessed with being efficient that we’ve stopped being effective.

No doubt, many areas of the healthcare system are overloaded. But maybe some of that strain is just a symptom of being fast rather than good. Maybe it’s the reason some speed-focused hospitals still keep pneumonia patients days longer than the national average. Maybe it’s the reason people make second and third trips to the emergency department when they don’t understand their diagnosis or treatment plan. Maybe an extra 20 minutes of end-of-life discussion on the oncology ward would have saved a tearful family days in the ICU.

Of course, like any professional should, I’m getting faster. I’ve got the numbers and the metrics to prove it. And I’m sure someone behind a desk somewhere is pretty pleased with that. But I’m not. For me, speed is a byproduct, a downstream result, a reward for striving to do things the right way each time.

Of course, like any professional should, I’m getting faster. I’ve got the numbers and the metrics to prove it. And I’m sure someone behind a desk somewhere is pretty pleased with that. But I’m not. For me, speed is a byproduct, a downstream result, a reward for striving to do things the right way each time.

That attempt at “good” probably means some of my patients wait a little bit longer than others. And nobody likes that. But at the end of our time together, they rarely seem upset. If they are in a rush, they don’t show it. Some of them even have the time to stop on the way out, turn around, and shake my hand.

And I have the time to stop and shake theirs.

Maybe for some jobs it is better to be fast than good. But I have been a clinician and I have been a patient, and “better fast than good” doesn’t work for me in either case. I guess it’s just a reassuring lie for those who no longer strive for quality.

For the rest of us, it’s better to be good, then fast.

December 22nd, 2015

One Strike … And You’re Out???

Elizabeth Donahue, RN, MSN, NP-C

I consider myself a fan of sports in general, but of baseball in particular. I grew up in a small town near Cape Cod, and I had no chance of escaping a fervent love for America’s pastime. My sister was the only girl on her T-ball team, my dad played church softball, and being born in Massachusetts, I watched endless Red Sox games from a tender age (I had no choice, really; there was only one TV in the Donahue household). To top it all off, we became a host family for college baseball talent playing in the Cape Cod Baseball League when I was about five, ensuring a seasonal parade of older brothers to teach me the rules of baseball over the course of my childhood summers.

One of the first and most basic of the rules was that each batter gets three strikes before their turn at bat is up. Recently, I’ve started to notice a trend in patient care that has left me to wonder — can I get more than one pitch in this game before I’m sent back to the dugout?

Everyone in healthcare is aware we are in the thick of flu season. Four months ago, we started sending emails and posting signs in practices asking patients to remember to get vaccinated, reminding them that they were protecting not only their own health but also that of the more vulnerable patients, family members, or coworkers around them. And yet, one after another, patients in the office have patently refused the vaccine from the first mention — citing an experience of developing an illness after their last flu vaccine. It may have been last year or ten years ago. It may have been a headache, a fever, a runny nose, vomiting, diarrhea (some symptoms not even associated with the flu!) or a combination of complaints. Despite all of the data, knowledge, and discussion I can present — the flu vaccine has no live ingredients! the timing was probably a coincidence! a real allergic reaction looks radically different from this! — I might as well have started the game on the disabled list. The vaccine’s only gotten one strike, and I’m out.

Everyone in healthcare is aware we are in the thick of flu season. Four months ago, we started sending emails and posting signs in practices asking patients to remember to get vaccinated, reminding them that they were protecting not only their own health but also that of the more vulnerable patients, family members, or coworkers around them. And yet, one after another, patients in the office have patently refused the vaccine from the first mention — citing an experience of developing an illness after their last flu vaccine. It may have been last year or ten years ago. It may have been a headache, a fever, a runny nose, vomiting, diarrhea (some symptoms not even associated with the flu!) or a combination of complaints. Despite all of the data, knowledge, and discussion I can present — the flu vaccine has no live ingredients! the timing was probably a coincidence! a real allergic reaction looks radically different from this! — I might as well have started the game on the disabled list. The vaccine’s only gotten one strike, and I’m out.

A few weeks ago, I was out to dinner with a close friend and her mother, both of whom I’ve known for years. My friend’s father had a sudden, serious illness requiring hospitalization a few years prior — long story short, it was complicated, involving multiple sequelae and considerations for his future treatment. When seeing a physician assistant in the emergency room following his acute illness, my friend’s mother questioned whether or not the treatment recommendation was the best choice for her husband’s care. The attending whose second opinion she sought agreed that the treatment may be detrimental and chose to implement another option. After sharing this with me at dinner, she expressed her fear of dealing with anyone but attending physicians going forward. I didn’t say anything at the time, empathizing with her, understanding that managing family illness is difficult and scary. But underneath I was thinking, don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater here, there are providers who aren’t attendings who can provide excellent care. One of them may even be that particular PA who simply did not have all of the information to make the best choice at that particular juncture. A coach doesn’t bench a player after one bad at bat, and batters typically perform better as they learn more about the pitcher, or in this case, the patient.

Of course, as a provider, I realize there are many times where the first strike is all you have — surgery comes to mind. I also understand that one of these things is just a game, and the other is very much real life. But in healthcare, thousands of decisions are debated, communicated, and implemented every day, and not every one of them is high-stakes. When we’ve swung at a single bad pitch, we may still deserve our full at bat. In order to convince patients, I think we need to point to evidence and invest time to establish trusting relationships — raising our “stats” in their eyes and hopefully showing them that we’ve still got a home run left in us.

December 16th, 2015

To Vaccinate Or Not

Scott Cuyjet, RN, MSN, FNP-C

In regard to mandatory vaccine laws, there is a new law in California, SB 277, which does not allow for religious or personal-belief exemptions. The law does however leave open the ability for a medical exemption. Previously, Mississippi and West Virginia were the only states to ban vaccination waivers based on religion. The law goes into effect for the fall 2016 school year and will be phased in over time. “Children who have a personal-belief exemption on file before Jan. 1, 2016 will have more time to comply with the law,” the LA Times reports. “Such children who are in nursery school or preschool must comply to enroll in kindergarten; those in elementary school must do so by 7th grade. Those already in junior high and high school will remain exempt.” Unvaccinated children would have to be home-schooled or do independent study.

When I first heard of this bill passing, I had mixed thoughts. There are people all across the country who are afraid of being overlegislated and subsequently losing the ability to have control over their lives and their families’ lives, and this is a prime example of that. Unfortunately, the law may not have its intended effect, as telling people what to do without choice often causes pushback in the opposite direction. We may actually see fewer people getting their kids vaccinated. With the new law, if people continue to choose not to get their kids vaccinated and the law is enforced, other infants, kids, pregnant moms, and health-compromised people might be safer at daycare and school — but not outside of daycare and school. Also, in a recent study in Pediatrics published March 3, 2014, researchers found that trying to change an antivaxxer’s opinion may actually make the problem worse.

I work as an FNP-C at a clinic for adolescents (ages 13–25) in California, and we get a significant number of patients who need vaccinations. The clinic where I work has a large population of recent immigrants with incomplete or missing records, and they need to continue their series or start it over in order to enroll in school. I was open to the research about vaccines possibly having negative effects such as autism, but the original research was falsified and subsequent research has not shown any correlation. Changes have been made to vaccines deemed less safe in the past. For instance, there was a question about risk versus benefit of the active/oral polio vaccine, as a very small group of kids being vaccinated were getting polio. There was enough evidence to compel people working in public health to assist in getting it changed to an inactive form, or IPV. What we have seen since the antivax information hit the media and people stopped vaccinating their children is a pertussis outbreak and a measles outbreak. A mom in Canada had all seven of her unvaccinated children come down with pertussis and now is questioning her choice not to vaccinate.A few months ago, there was an article in Scientific American about antivax parents refusing the vitamin K injection for their newborns, which can put them at risk for internal bleeding. These examples show how dangerous ignorance and distrust can be.

The bottom line is that if there are any risks of vaccination, they have been shown historically to be outweighed by the benefits, at least for the older vaccines.

December 9th, 2015

Be a Quality Preceptor: Our Legacy Depends On It

Bianca Belcher, MPH, PA-C

The PA brand is known for its excellent clinical care, reliability, and a keen ability to connect with patients. I feel strongly that as a practicing PA it is part of my duty to the profession to ensure that graduating PAs maintain that legacy. I sometimes worry that expanding too quickly will dilute our profession. Flooding the field with intelligent young PAs who perform well in the classroom but lack meaningful experience in caring for or relating to patients changes our professional identity. As practicing PAs (and other providers that precept our students), we must do our part to help prevent this by giving each and every student who rotates with us a quality experience. I precept several students each year and am no stranger to the amount of extra time and effort it requires, but we can’t forget that these students will soon be certified and could be taking care of our friends and family.

The PA brand is known for its excellent clinical care, reliability, and a keen ability to connect with patients. I feel strongly that as a practicing PA it is part of my duty to the profession to ensure that graduating PAs maintain that legacy. I sometimes worry that expanding too quickly will dilute our profession. Flooding the field with intelligent young PAs who perform well in the classroom but lack meaningful experience in caring for or relating to patients changes our professional identity. As practicing PAs (and other providers that precept our students), we must do our part to help prevent this by giving each and every student who rotates with us a quality experience. I precept several students each year and am no stranger to the amount of extra time and effort it requires, but we can’t forget that these students will soon be certified and could be taking care of our friends and family.

I urge all PAs to open up their practices to one or more students from a local/regional program (a list of programs can be found here). Share your pearls with them. Mentor them. Help create a positive learning environment for them to gain not only experience, but also (and maybe more importantly) a sense of responsibility. Your efforts will create the foundation that allows our high-quality PA brand to remain potent and durable. The investment is worth it.

PA Preceptor Handbook (Physician Assistant Education Association membership required for e-version or you can request from your affiliate PA institution):

; [/php]/images/AU000_cmaniates.jpg)

; [/php]/images/AU000_hreed.jpg)

; [/php]/images/AU000_edonahue.jpg)

; [/php]/images/AU000_scuyjet.jpg)

; [/php]/images/AU000_bbelcher.jpg)