October 5th, 2017

An Old Procedure, A New Beginning

Emily F. Moore, RN, MSN, CPNP-PC, CCRN

Emily F. Moore, RN, MSN, CPNP-PC, CCRN practices pediatric cardiovascular care across the Pacific Northwest.

“My heart hurts,” said Brooklyn, then three years old, as she grabbed her chest and sat down. Quickly checking the girl over, Brooklyn’s parents felt her heart indeed pounding in her chest, and took her to the emergency department. There, they were shocked to hear that their daughter was in cardiac arrest. Shortly afterward, Brooklyn was diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension. The following few years brought a multitude of procedures, medications, and doctor appointments.

After two years, the disease started to take its toll, and Brooklyn had increasing cyanosis. On the recommendation of their doctors, the family moved to Seattle to be at sea level. Initially, Brooklyn’s symptoms improved, but over the years, her health steadily declined. At eight years old, she was maxed out on medications, no longer growing, and unable to walk without shortness of breath — and her family was looking at transplantation as the only option. Unfortunately, due to her rapidly deteriorating disease combined with constant insurance obstacles, transplantation seemed out of reach.

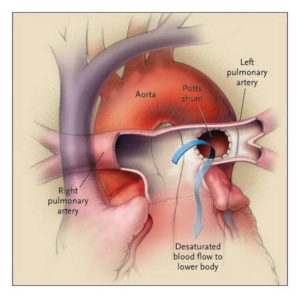

Looking as if they were out of options, their pulmonary hypertension specialist Dr. Delphine Yung introduced another option she had read about. It involved repurposing the once failed Potts shunt to redirect excess blood in the pulmonary artery to the aorta. (Created in 1940, the Potts shunt was meant to be used for the reverse purpose, to augment pulmonary blood flow. However, it quickly went out of favor because in many cases it had worked too well, causing pulmonary hypertension.)

Looking as if they were out of options, their pulmonary hypertension specialist Dr. Delphine Yung introduced another option she had read about. It involved repurposing the once failed Potts shunt to redirect excess blood in the pulmonary artery to the aorta. (Created in 1940, the Potts shunt was meant to be used for the reverse purpose, to augment pulmonary blood flow. However, it quickly went out of favor because in many cases it had worked too well, causing pulmonary hypertension.)

Presenting her idea in a patient care conference with the cardiac surgical team, Dr. Yung explained that she had heard of the Potts shunt being used successfully in a few cases of pulmonary hypertension abroad and then later in the U.S., and she felt it held potential for Brooklyn. Our chief of cardiac surgery, Dr. Jonathan Chen, stated his concerns about the complexity of the surgery for patients with pulmonary hypertension. However, after researching the revised use of this shunt further, he was persuaded that it was worth going out on a limb to try to improve Brooklyn’s life.

Both Dr. Yung and Dr. Chen approached Brooklyn’s family with the idea of the repurposed shunt placement. Her parents were understandably nervous about the idea, as their daughter would be one of the few patients in the world to undergo this surgery. But knowing they were out of options, the family agreed to move forward with the surgery.

The operation by Dr. Chen went smoothly, and Brooklyn’s vital signs indicated nearly instant relief for her heart.

Within a few weeks of surgery, Brooklyn’s medications were decreased and then stopped. She was weaned off oxygen, and a central line that had been in place for years was removed. She was finally able to go swimming and start living life to her full potential. Her parents were beyond grateful for the success of the procedure. To paraphrase Dr. Chen, it took an incredible amount of courage for these parents to try the shunt and trust the health care team with this decision. [He also reflected how, as a wedding is the mark of a new life, so was this procedure for Brooklyn and her family. And as with a well-known wedding tradition, her case even involved something old (the abandoned procedure), something new (its new use), something borrowed (the shunt and procedure techniques), and something blue (the cyanosis, now improved postprocedure).]

Brooklyn is now nearly three years post-surgery and doing remarkably well. Dr. Yung and Dr. Chen have one other patient who has since undergone the procedure with a similar outcome.

I am often in awe of the power of medical science to help us achieve advances in health care, and this particular story, and the remarkable level of success for the patient, are the best example of this I have witnessed.

Well done