November 16th, 2013

A Critical Time for Health Research?

Siqin Ye, MD

Several Cardiology Fellows who are attending AHA.13 in Dallas this week are blogging for CardioExchange. The Fellows include Vimal Ramjee, Siqin Ye, Seth Martin, Reva Balakrishnan, and Saurav Chatterjee. You can read the next fellowship post here. For more of our AHA.13 coverage of late-breaking clinical trials, interviews with the authors of the most important research, and blogs from our fellows on the most interesting presentations at the meeting, check out our AHA.13 Headquarters.

Hello everyone,

I’m excited to be part of the blogging team for CardioExchange’s coverage of the American Heart Association 2013 Scientific Sessions!

On my flight to Dallas this morning, as is my habit, I caught up on the stack of magazines and journals that were accumulating on my desk. As it happens, one of them was this week’s JAMA special issue, “Critical Issues in US Health Care.”

The articles inside were riveting. In a Viewpoint piece, “Toward a New Social Compact for Health Research,” Dr. Harvey Fineberg talks about the retrenchment of US investment in health research, as evidenced by declining NIH and overall funding in the last decade. In a separate Viewpoint, Dr. Donald Berwick discusses the “toxic politics” of healthcare. “Public trust in science is eroding”, he points out, while healthcare professions have largely been silent and have not vigorously advocated for needed reforms.

I think Dr. Berwick’s points also apply to the pressures faced by health researchers. Many of us engage in research because we believe that the advancement of medical science is a worthwhile pursuit and a societal good. But we don’t do a good job advocating for our beliefs in the public arena, so that there are far more members of Congress willing to fight against cuts in fighter plane orders than those who fight against cuts in the NIH budget. On this point, Dr. Fineberg writes:

“Perhaps no young physician scientists embark on a research career thinking it is a position in sales, but they quickly learn how necessary it is to convince others of the value and promise of their own research ideas. Today, it is equally important for health researchers to gain public confidence and trust in the value and promise of the whole of the scientific research enterprise for health.”

In my mind, this process of engaging the public can start with small steps: sharing on my Facebook feed an article debunking anti-vaccination myths, or, as my research shop has decided to do, prominently displaying the NIH logo on our posters and presentations. As I explore the scientific offerings at this year’s AHA meeting, I am also excited to see the AHA exploring new ways to engage the public, such as the mobile app that allows attendees to easily share the sessions they find interesting on social media.

But I also wonder about what more we can do. For instance, the American College of Cardiology recently added an “Ask-An-Expert” feature to their patient website to directly connect the public to ACC members. This inspired me to wonder: what if we also built an “Ask-A-Researcher” forum, featuring prominent researchers taking questions directly from the general public, similar to a Reddit AMA?

What do you think? How can we, as researchers and healthcare professionals, better engage the public?

November 15th, 2013

Hypertension Treatment Algorithm Fills in for Missing Guideline

Larry Husten, PHD

When the AHA and the ACC released four updated clinical guidelines earlier this week, a fifth document, the hypertension guideline, was conspicuous by its absence. According to the AHA and the ACC, the authors of the hypertension document have chosen to publish it independently. (No word has yet emerged about their reasons for doing so or when the document will be published.) In response, the AHA and the ACC announced that they would publish full hypertension guidelines in 2014, but in the meantime would publish a brief interim document. Now the two organizations, in conjunction with the Centers for Disease Control, have published a scientific advisory on the AHA and the ACC websites.

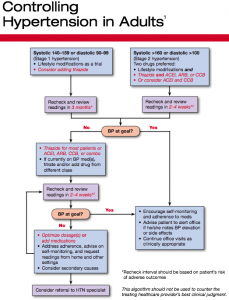

A treatment flowchart, Controlling Hypertension in Adults, breaks no major new ground but provides clinicians with a simple and easy hypertension algorithm. It eliminates the controversial “prehypertension” category of the previous guideline. Stage 1 hypertension is defined as an adult with a systolic blood pressure of 140-159 or a diastolic blood pressure of 90-99. Lifestyle modifications are first line therapy. Physicians may “consider adding” a thiazide diuretic. Stage 2 hypertension is anyone with a systolic blood pressure over 160 or a diastolic blood pressure over 100. In addition to lifestyle modifications, physicians should prescribe a thiazide diuretic and another drug, either an ACE inhibitor, an angiotensin-receptor blocker, or a calcium-channel blocker. An ACE inhibitor/calcium-channel blocker combination may also be considered.

The document also offers suggestions for choosing drugs in the presence of common conditions and provides a brief summary of the benefits of lifestyle modifications.

Here is the flowchart (click to enlarge):

November 12th, 2013

Promising GSK Heart Drug Misses Primary Endpoint in 15,000-Patient Trial

Larry Husten, PHD

GlaxoSmithKline announced today that the first of two pivotal phase 3 trials with a new drug, darapladib, had failed to meet its primary endpoint. Full results of the trial will be presented at a scientific meeting.

The STABILITY trial (STabilisation of Atherosclerotic plaque By Initiation of darapLadIb TherapY) tested the effect of darapladib, an investigational Lp-PLA2 inhibitor, in more than 15,000 patients with chronic coronary heart disease. GSK reported a nonsignificant 6% relative risk reduction associated with the use of darapladib (versus placebo) in the time to first occurrence of any major adverse cardiovascular event (the composite of myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death).

The company said there were statistically significant reductions “in some of the pre-defined secondary endpoints that require further analysis.” The company reported “no major imbalance in serious adverse events” in the trial but noted that diarrhea and odor “occurred at a similar frequency to that seen in Phase II.”

Darapladib is an oral inhibitor of Lp-PLA2 (lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2), an inflammatory marker associated with atherosclerosis and plaque rupture. GSK said that a second phase 3 trial, SOLID-TIMI 52, which is testing the effect of darapladib in more than 13,000 patients with acute coronary syndromes, will continue and will help the company “determine our next steps.”

GSK took over the development of darapladib when it acquired Human Genome Sciences last year.

November 12th, 2013

After Long Wait, Updated U.S. Cardiovascular Guidelines Now Emphasize Risk Instead of Targets

Larry Husten, PHD

Updated cardiovascular health guidelines were released today by the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American College of Cardiology (ACC). The guidelines are designed to provide primary care physicians with evidence-based expert guidance on cholesterol, obesity, risk assessment, and healthy lifestyle.

The new guidelines reinforce many of the same messages from previous guidelines, but also represent a sharp change in philosophy. That change is most evident in the new lipid guidelines, in which the focus has shifted away from setting numerical targets for cholesterol levels in favor of treatment decisions based on individual risk status.

“This guideline represents a departure from previous guidelines because it doesn’t focus on specific target levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, commonly known as LDL, or ‘bad cholesterol,’ although the definition of optimal LDL cholesterol has not changed,” said Neil J. Stone, chair of the lipid expert panel that wrote the new guideline. “Instead, it focuses on defining groups for whom LDL lowering is proven to be most beneficial.”

The long-awaited and often controversial guidelines are the successors to the extremely influential NHLBI guidelines, including the Adult Treatment Panel (ATP) series of guidelines that brought cholesterol to the consciousness of millions of people. Earlier this year the NHLBI announced that it would no longer issue guidelines but would, instead, provide support for guidelines produced by other organizations. Following the NHLBI announcement, the AHA and the ACC said that they would take over publication of the guidelines.

This summary of the guidelines and the news around them is broken out into several topics. Click on one of the links below to jump ahead.

Statins Indicated for Four Broad Groups

The new lipid guideline identifies four groups of patients for whom statin therapy is indicated:

- People who already have cardiovascular disease (secondary prevention).

- People with LDL levels 190 mg/dL or higher. Many of these will have familial hypercholesterolemia.

- People with type 2 diabetes who are between 40 and 75 years of age. (This is the age group where the evidence base is strongest.)

- Patients who are not known to have cardiovascular disease but who have an estimated 10-year risk for cardiovascular disease of 7.5% or higher and who are between 40 and 75 years of age. (The guideline provides formulas and links for calculating 10-year risk.)

The guideline recommends high-intensity statin therapy for the first two groups. The last two groups are suitable for moderate-intensity therapy, though some patients with type 2 diabetes may benefit from high-intensity treatment.

“We were unable to find solid evidence to support continued use of specific LDL cholesterol or non-HDL treatment targets,” said Stone. Although targets have been used extensively in clinical practice, he said that treating to specific targets can often lead to undertreatment of high-risk groups and overtreatment of low-risk groups.

Routine use of non-statin therapies is not endorsed in the new guideline. “We found that non-statin therapies really didn’t provide an acceptable risk reduction benefit compared to their potential for adverse effects in the routine prevention of heart attack and stroke,” said Stone.

Stone also pointed out that there will be some people who may not be in one of the four groups but who may still benefit from statin treatment. “We provide guidance for physicians to try to determine whether or not” these patients would also qualify.

No Endorsement for Broad Use of New Risk Markers

In the new guideline for assessing cardiovascular risk in adults, the risk equations now predict risk for both heart attack and stroke — previous guidelines focused exclusively on coronary heart disease. “We realized quickly that we were leaving a lot of risk on the table by not also including stroke,” said the risk assessment co-chair, Donald Lloyd-Jones. He said that including stroke was particularly important for women and African-Americans.

After much debate, the committee that developed the guideline found that new risk markers should not be used for routine risk assessment. The new guideline relies on the traditional risk factors of age, race, sex, total and HDL cholesterol levels, blood pressure level, blood pressure treatment status, diabetes status, and current smoking status.

The committee identified four additional markers, said Lloyd-Jones “that may be considered by clinicians and patients if there is still uncertainty after — and I emphasize only after — they have performed the risk equation exercise.” The four additional markers are history of premature cardiovascular disease in the immediate family, coronary artery calcium score, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and the ankle-brachial index. The guideline specifically recommends against the routine use of carotid intima-medial thickness (CIMT), saying that it may be useful as a research tool but that broader use is not warranted because of the large amount of inter- and intra-operator variability.

Primary care physicians have little training or expertise in dealing with obesity, said Donna Ryan, co-chair of the obesity guideline. Because they are “operating in a culture that has a lot of misinformation about weight management,” the guidelines are designed to provide authoritative information that primary care physicians can use to help their patients. The guidelines offer advice about several key questions:

- Who needs to lose weight?

- What are the benefits of weight loss?

- How much weight loss is needed?

- What is the best diet?

- What is the efficacy of lifestyle intervention?

- What are the benefits and risks of bariatric surgical procedures?

The committee recommends that physicians continue to use current BMI and waist circumference cut points. They state that benefits begin with weight loss as little as 3%, but the committee urges physicians to focus on helping their patients achieve a 5-10% weight loss in the first 6 months.

The committee examined the evidence for at least 17 different diets. “We came down loud and clear that there is no ideal diet for weight loss and that there is no superiority for any of the diets we examined,” said Ryan. The choice of diet “should really be determined by the patient’s preferences and health status,” she said.

The guidelines offer yet another endorsement for bariatric surgery for high-risk patients, including adults with a BMI of 40 or higher and adults with a BMI of 35 or higher who have two other cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes or high blood pressure. The guideline does not recommend weight loss surgery for people with a BMI under 35 and does not recommend one surgical procedure over another.

The new guidelines don’t cover pharmacotherapy, including the two new obesity drugs approved in the past year. Ryan said the committee hoped to address this subject in future updates.

The new lifestyle management guideline focuses on diet and exercise, said committee co-chairs Robert H. Eckel and Alice Lichtenstein. “The new focus,” said Eckel, is to “increasingly emphasize dietary patterns” such as the Mediterranean Diet or the DASH diet. These diets feature fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, include low-fat dairy products, poultry, fish, and nuts, and limit red meat, sweets, and sugar-sweetened beverages. The committee recommends limiting intake of saturated fat, trans fat, and sodium. Finally, they recommend that physical activity should average 40 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity 3-4 times a week.

The new guidelines seek to emphasize a global assessment of risk, and that statin and lifestyle treatment should be aimed to reduce risk and not just an isolated LDL number. Although LDL cholesterol remains important, said Lloyd-Jones, statins “don’t only treat cholesterol… really they are risk-reducing agents.”

Lloyd-Jones calculated that under the old ATP 3 guidelines, treating people with a 10-year risk for coronary disease over 20% and people with diabetes would lead to treatment in about 15-16% of U.S. adults. Under the new framework, the four criteria, including the 7.5% threshold for primary prevention, results in 31% of American adults being eligible for statin treatment. This is about the same percentage of people who would have been eligible under the old criteria if the threshold had been lowered to a 10%, 10-year risk plus diabetes, said Lloyd-Jones.

“I think the way to think about it is that with the new equations and the new approach we are actually a lot smarter about identifying the people who will benefit from risk reduction therapies, but we’re not necessarily treating all that many more people than if we were using the old optional level,” he said.

“We weren’t concerned with treating more or less people,” said Stone. “We were concerned with treating the people who benefit the most.”

Asked whether physicians may be confused by the new change in emphasis and the absence of target treatment goals, Stone said that “once clinicians get used to this approach they may find it a lot simpler.” Lloyd-Jones explained that “we’re not abandoning the measurement of LDL, because it’s perhaps our best marker of understanding whether patients are going to achieve as much benefit as they can with the dose of statin that they can tolerate, and it’s also for the clinician an important marker of adherence. If the LDL is not coming down it’s an important flag that there may be a problem.” Stone said that a follow-up lipid panel should not be used “to see whether you’ve reached a target but to encourage a discussion that focuses on both adherence” to lifestyle and appropriate statin treatment.

It is worth noting, however, that although the lipid guideline has placed less emphasis on LDL, the lifestyle management guideline remains yoked to LDL. The recommendation against saturated fat is based on epidemiology and studies that show the effect on LDL of saturated fat. “The effect of reductions in saturated fat on LDL-C are unequivocal,” said Eckel.

Where Are the Hypertension Guidelines?

One guideline — the also highly-anticipated successor to the JNC hypertension guideline — was not released today and will not be published by the AHA and the ACC. AHA President Mariell Jessup sent the following statement:

“The NHLBI did originally commission a writing panel to develop the next JNC hypertension guidelines as part of this entire prevention portfolio. When the NHLBI asked the ACC/AHA Joint Task Force to assume the guideline process moving forward, the hypertension writing panel — as of this date — declined to be a part of the process. Thus, the ACC/AHA will proceed to develop hypertension guidelines, in conjunction with a number of other relevant societies (primary care and specialty groups), beginning in 2014.

What I do not know currently is the status of the manuscript that the originally commissioned hypertension writing panel created, nor am I certain that any manuscript that may be published will be called JNC 8.

In the meantime, the ACC/AHA, in conjunction with the CDC, will unveil a hypertension algorithm developed primarily to be part of an overall systems approach for primary care clinicians, to enhance the detection and control of hypertension in this country. We are very excited about this statement and hope it will be incorporated in many offices.”

November 12th, 2013

Building Quality of Care for Adult Congenital Heart Disease Patients

Michelle Gurvitz, MD MS and Ariane Marelli, MD, FRCP(C), MPH

CardioExchange Editor Harlan Krumholz interviews Michelle Gurvitz and Ariane Marelli about their study group’s JACC paper, for which they developed the first set of quality indicators (QIs) for adult congenital heart disease (ACHD) care. Using existing literature and guidelines and a modified Delphi process, a total of 55 QIs were identified, including 8 for atrial septal defects; 9 for aortic coarctation; 12 for Eisenmenger; 9 for Fontan; 9 for D-transposition of the great arteries; and 8 for tetralogy of Fallot.

Krumholz: What are your three favorite QIs among the group?

Gurvitz and Marelli: Given the diversity of conditions and the multiple indicators per condition, it is difficult for us to choose three “favorites” among the group. We would rather focus on groups of measures we think have potential for wider impact. These groups include routine visits, surveillance testing, and discussions regarding reproductive health.

One group that we think may be most actionable for ACHD patients are the indicators regarding annual surveillance. This includes recommendations for routine follow up visits as well as regular interval testing. There are little data on which to base the frequency of visits and surveillance testing for this population, however, there was significant agreement among the international guidelines and the expert panelists for certain types of conditions and the recommended visits and testing. Gathering further information on practice patterns and relationships to outcomes will better inform our practices in the future.

From an awareness perspective, the working groups and expert panelists sought to “raise the bar” for practitioners in certain areas. One example would be that the documentation of discussions regarding pregnancy and reproductive health were included for multiple conditions. This speaks to the importance of addressing this topic in the context of the cardiology practice.

It will be important to gather further data on these measures and their relationship to outcomes. This will help inform future modifications of measures and potentially impact resource utilization and cost effectiveness.

Krumholz: What was the measure that you did not adopt that you think is important and should be considered for the future?

Gurvitz and Marelli: In the development process, there were many measures that “fell off” at different stages of the process for reasons of evidence, validity, or feasibility; we expect that others may also fall off during the operationalization process and true feasibility testing of data collection from medical records. This does not mean these areas of care are not important, it typically means that there is disagreement about some aspect of the practice or there is difficulty in consistent and reliable measurement.

There were a few measures initially proposed regarding the timing of surgical interventions (e.g., pulmonary valve replacement in tetralogy of Fallot and tricuspid valve intervention in patients with systemic right ventricles) that were either not recommended by the working group or rejected based on the panel scores. This happened because the working groups or the panelists did not think the available information was strong or consistent enough to support a quality measure at this time. We hope that over time, as more data are collected, we will have enough evidence to propose surgical timing or referral as a quality measure.

In a completely separate area of interest, there were a number of measures proposed by the working groups and mentioned at the expert panel meeting that might apply across many CHD populations. Some examples would be measures such as hepatits C testing for people with surgery prior to 1992 (only proposed for Fontan patients in our group), routine vaccinations, genetic screening, or even transition planning. Developing measures applicable to a larger population may be an endeavor considered in the future.

Krumholz: Will these QIs be measured at all major centers?

Gurvitz and Marelli: The measures still require testing for feasibility of data collection and relationship to outcomes. They are at a stage that we think is useful for programs wishing to pursue internal quality improvement , but they are not meant to be considered as performance measures. We hope that many centers will adopt all or some of the QIs for internal use and that they share data and experiences so we can all learn from the process. Also, the measures are designed for use by both ACHD specialty cardiologists and internal medicine cardiologists who may follow ACHD patients in their practices. We are hoping to test the measures in multiple environments in the future.

We are certain — and it is expected — that the measures will be modified over time as more data become available. We encourage collaborative efforts with cardiologists, groups, or centers who are interested in their application. We hope to pool collected data to try to improve the measures over time.

Krumholz: Will they be publicly available? If not, why not?

Gurvitz and Marelli: All of the measure titles, categories, and scores are listed in the tables in the manuscript. Specific numerators, denominators, and exclusion criteria are easily available on request beyond what is published.

Krumholz: Who will take responsibility to promote improved quality of care for these patients?

Gurvitz and Marelli: We feel it is the responsibility of every practitioner seeing ACHD patients to try to improve their quality of care. With this effort, we hope to participate in “shifting the curve” in improving care for ACHD patients.

Some patient advocacy organizations, such as the Adult Congenital Heart Association, are calling for improved quality and discussing how to potentially accredit ACHD centers. The recent approval by the American Boards of Internal Medicine and Pediatrics to certify a specialty in ACHD is a tremendous step forward. The American College of Cardiology, too, has been very supportive of efforts at building and measuring quality in CHD care with their efforts in data collection tools such as the IMPACT Registry and efforts in knowledge translation in collaboration with other organizations.

We hope this type of interest and support in quality improvement will continue among these and other national and international organizations involved in the care of ACHD patients.

November 11th, 2013

Selections from Richard Lehman’s Literature Review: November 11th

Richard Lehman, BM, BCh, MRCGP

CardioExchange is pleased to reprint this selection from Dr. Richard Lehman’s weekly journal review blog at BMJ.com. Selected summaries are relevant to our audience, but we encourage members to engage with the entire blog.

JAMA 6 Nov 2013 Vol 310

Association of Testosterone Therapy With Mortality, MI, and Stroke in Men With Low Testosterone Levels (pg. 1829): Testosterone is the root of all evil, according to some. Or else it is the essence of manly life. Both, probably. You can find any number of websites touting the benefits of testosterone replacement therapy and there is an active “low T” advertising campaign in the USA. It is a relatively evidence-free area, and in my view it remains so after this study, which compared outcomes in men with low testosterone and coronary heart disease who were given testosterone to outcomes in the majority who were not. The authors looked at 8709 US Armed Forces veterans who presented for coronary angiography and happened to have had their testosterone measured and found to be lower than 300 ng/dL (about 11 nmol/L). Of these, 1223 started testosterone therapy after a median of 531 days following coronary angiography. At a mean follow-up of three years, these men had a higher rate of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke. But there is simply no way to adjust for all possible dissimilarities between these groups.

November 11th, 2013

Case: An Ironman with a Proximal Circumflex Lesion

John Ryan, MD, JAMES BECKERMAN, M.D. and James Fang, MD

A 48-year-old man who runs 4 to 6 Ironman races per year reports non-exertional chest pain and is referred for a stress echocardiogram. His two sisters suffered MIs and died in their fifties, and his brother underwent CABG at age 49.

The patient goes for 17 minutes on the Bruce stress protocol, with lateral and anterolateral wall hypokinesis at peak stress. He is referred for coronary angiography, which shows a 50% proximal circumflex lesion deemed best treated with medical management.

He is referred to me and asks me how much should he exercise — specifically, whether he should run an Ironman in the Grand Tetons this coming weekend.

What would you advise this patient?

1. Keep running at your current level. (If he has an MI during a marathon, I will obviously feel awful.)

2. Keep running for exercise, but do not compete in marathons.

3. Simply reduce the amount of exercise you do. (It seems strange to tell someone to exercise less.)

4. Reduce your level of exercise, and repeat a stress test in 3 months. If the stress test is normal, you will have a green light to compete again.

5. Something else?

Response (November 11, 2013)

Sometimes I like to think about these situations backwards. A man with very high functional capacity who completes long-distance triathlons is diagnosed with a 50% circumflex lesion. If we assume that an abnormal stress test is generally caused by high-grade lesions, then the 50% circumflex stenosis is potentially not the cause of the positive stress test in this case. The patient could actually have had a false-positive stress test with non-anginal chest pain and an incidental 50% non-culprit lesion. Even if the lesion is causing the positive stress test (FFR would be another consideration), then we still doubt that he is experiencing classic angina because he has been training for hours at a time with no symptoms.

So let’s assume we are diagnosing coronary artery disease that is likely asymptomatic but we still want to recommend that this runner limit his exercise. In that case, it would be a more consistent practice pattern to recommend stress-test screening for CAD before allowing anyone to train for endurance sports — or even to advocate coronary angiography, given the possibility of false-negative stress tests. But that is obviously not how we practice — or how we should practice. In general, when a patient tells you that he or she wants to run a marathon, you take a history and make sure there is no angina, or you might consider an electrocardiogram. Stress testing for asymptomatic patients is generally reserved for those older than 65, or for younger patients who are at significant risk for coronary disease.

This patient likely had the same 50% circumflex lesion during the previous Ironman race he completed 2 months ago and during his 100-km bike ride the weekend before seeing you. I would tell him that his risk goes up in a small but incremental way during these endurance events and that limited evidence suggests that persistent endurance training is associated with arrhythmia and, possibly, myocardial fibrosis.

Fortunately, the event rate during endurance races is low. The 2012 NEJM article from the RACER Study Group showed that the risk for cardiac arrest during marathons is on the order of 1 in 100,000. The risk in triathlons is similar, with the majority of deaths during the swim. ESPN recently published an article, called “Trouble Beneath the Surface,” about deaths during triathlons, especially the swim component. The reasons are unclear, but there are theories about autonomic conflict, when both the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems are activated simultaneously and may provoke arrhythmias. In terms of marathons, note that a higher percentage of events occurs during the last mile, as people have a surge in adrenaline and speed when they are trying to achieve a certain time or beat a personal record.

A big-picture question is whether training more than 15 to 20 hours a week is good for our long-term heart health. I tend to agree with practitioners in this field who suggest that you are not doing multiple long-distance triathlons or marathons primarily for heart health — something else is motivating you. By taking on that additional training, the person must appreciate the possibility of short- or long-term cardiac consequences. And, of course, cardiologists have their own biases. Some who support endurance exercise may be more likely to do it themselves. To be fair, the debate is less about comparing endurance activity to a sedentary lifestyle than about comparing endurance exercise to a lower dose of activity.

Regarding your patient, I would not tell him that he may never participate in an endurance event again. I would be realistic about his risks and recommend that he take any symptoms on the course very seriously. He should also avoid bursts of speed to achieve a certain time. He should do everything he can medically to reduce his risk, such as taking aspirin and a statin. I would empower him with information that is realistic without being alarmist, and help him reach the decision that makes the most sense for him.

Response (November 20, 2013)

Jim Fang, MD

This fit middle-aged man has aggressive atherosclerosis (an obstructive lesion at age 48) and appears to be symptomatic. A 50% angiographic stenosis, corresponding to 70% cross-sectional stenosis, can produce angina. This correlation is why many of the classic angiographic CAD studies have deemed 50% angiographic stenosis to be clinically relevant. FFR (or IVUS to demonstrate true cross-sectional stenosis) may have proven this, but the stress test shows ischemia in the distribution of the lesion, and the patient has typical symptoms. I believe he has probably developed ischemic preconditioning, which likely has allowed him to have this degree of exertional capacity in addition to his peripheral muscle and respiratory conditioning.

Medical therapy would be my first recommendation (aspirin, statin, beta-blocker), but the chronotropic effects of beta-blockade are likely to affect the patient’s athletic performance. I would not be comfortable with prolonged-demand ischemia despite the high workload, given the family history of MI and early death. Although ventricular fibrillation from chronic ischemic heart disease is not common, as noted in the NEJM paper that Dr. Beckerman cites, it may have a familial tendency.

Therefore, I would curtail the patient’s marathon running until he decides what course he wants to elect. I agree that running 4 to 6 Ironman races per year is not of any health benefit to him. Remember, Jim Fixx died of sudden cardiac death.

Wrap-Up (November 25, 2013)

John Ryan, MD

After extensive consultation and discussion, the patient and I opted for aspirin 81 mg, atorvastatin 40 mg, and continued exercise. However, I advised him to take any chest-pain symptoms seriously and also prescribed nitroglycerin for use as needed. He has not had any symptoms while exercising and has reduced his intensity to half marathons for the next 6 months. Since he and I first met, he has successfully run one noncompetitive half marathon, has opted not to run competitively, and is no longer trying to break personal records.

November 9th, 2013

Yet Another Blow to Combination Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System Blockade

Larry Husten, PHD

ACE inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers have been found to effectively slow progression of kidney disease. It has been theorized that dual blockade of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) might prove even more beneficial, but these hopes have not been realized. Now a new trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine throws further cold water on the once-promising hypothesis.

In the Veterans Affairs Nephropathy in Diabetes (VA NEPHRON-D) trial, Linda Fried and colleagues randomized type 2 diabetics with proteinuric kidney disease already receiving the angiotensin-receptor blocker losartan to either the ACE inhibitor lisinopril or placebo. The trial was stopped early by the data and safety monitoring committee due to safety concerns and the low likelihood that the trial would be able to yield a significant difference in the primary end point.

In the end, 1,448 patients were randomized and followed for 2.2 years. The primary endpoint — decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR), end-stage renal disease (ESRD), or death — occurred in 152 patients in the monotherapy group versus 132 in the combination group (hazard ratio for combination therapy: 0.88, CI 0.70-1.12, p=0.30). There was a trend toward benefit for the secondary endpoint of GFR decline and ESRD (HR 0.78, CI 0.58-1.05 p=0.10). There were no significant differences in mortality or cardiovascular events.

There was a significant increase in risk for hyperkalemia and acute kidney injury in the combination group compared with the monotherapy group:

- hyperkalemia: 6.3 versus 2.6 events per 100 person-years (p<0.001)

- acute kidney injury: 12.2 versus 6.7 events per 100 person-years (p<0.001)

The authors note that the results are consistent with the ONTARGET trial, in which the combination of an ACE inhibitor and an ARB also resulted in an increased risk for adverse events. Combination therapy also proved unsafe in the ALTITUDE trial, which tested the direct renin inhibitor aliskiren in addition to an ACE inhibitor or an ARB.

In an accompanying editorial, Dick de Zeeuw wonders whether these trials indicate the end of the dual therapy hypothesis. He writes that these “failed” trials “suggest that improvement in surrogate markers — lower blood pressure or less albuminuria — does not translate into risk reduction.” Combination therapy “can be resuscitated only if we can show renal and cardiovascular protection in a defined group of patients in whom the desired decreases in blood pressure, albuminuria, or both are achieved without major increases in potassium levels or other side effects.”

November 7th, 2013

FDA Seeks to Eliminate Trans Fat from Food in the U.S.

Larry Husten, PHD

The FDA said today that it would begin to take efforts to remove trans fat from food in the U.S. The agency has made the “preliminary determination that partially hydrogenated oils (PHOs), the primary dietary source of artificial trans fat in processed foods, are not ‘generally recognized as safe’ for use in food.”

If the FDA’s preliminary determination is made final then manufacturers will be required to reformulate products containing PHOs. The FDA will seek comments on the proposal for 60 days “to gain input on the time potentially needed for food manufacturers to reformulate products that currently contain artificial trans fat.”

“While consumption of potentially harmful artificial trans fat has declined over the last two decades in the United States, current intake remains a significant public health concern,” said FDA Commissioner Margaret Hamburg. “The FDA’s action today is an important step toward protecting more Americans from the potential dangers of trans fat. Further reduction in the amount of trans fat in the American diet could prevent an additional 20,000 heart attacks and 7,000 deaths from heart disease each year – a critical step in the protection of Americans’ health.”

Trans fat has long been known to raise LDL cholesterol. The FDA cited an Institute of Medicine (IOM) report that concluded that “trans fat provides no known health benefit and that there is no safe level of consumption of artificial trans fat.”

Trans fat consumption in the U.S. has declined dramatically in recent years. In 2006, trans fat content became a standard part of food labels. Trans fat intake dropped from 4.6 grams per day in 2003 to 1 gram per day currently, according to the FDA. Nevertheless, trans fat is still contained in some processed foods, including, according to the FDA, desserts, microwave popcorn products, frozen pizzas, margarines, and coffee creamers.

“The artery is still half clogged,” CDC director Thomas R. Frieden told the New York Times. “This is about preventing people from being exposed to a harmful chemical that most of the time they didn’t even know was there.”

November 7th, 2013

Internal Mammary Artery Grafting During CABG: How Common, How Effective?

Mark Hlatky, MD

CardioExchange’s John Ryan interviews Mark A. Hlatky about his research group’s analysis of the prevalence and effectiveness of internal mammary artery grafting during CABG procedures performed in Medicare patients. The study is published in JACC.

THE STUDY

In a study of Medicare beneficiaries aged ≥66 years who underwent isolated multivessel CABG from 1988 to 2008, researchers used a multivariable propensity score to match patients with and without an IMA graft (more than 60,000 patients in all, median follow-up of 6.8 years). IMA use rose from 31% of CABG procedures in 1988 to 91% in 2008. Rates of all-cause mortality, MI, and repeat revascularization were significantly lower in patients who underwent IMA grafting than in those who did not.

THE INTERVIEW

Ryan: Using Medicare claims data, you show that IMA use for patients undergoing CABG has increased and is associated with better outcomes. Are you confident about the coding of IMA use in administrative claims?

Hlatky: The coding of procedures is, in general, pretty accurate because of the close tie to billing for surgery. So I think the IMA codes are good here.

Ryan: Why do some surgeons not use an IMA? In 2008, only 8% of patients did not have an IMA.

Hlatky: Early on, I don’t think that all surgeons were convinced an IMA was necessary, and it certainly increased the length and difficulty of the procedure. Once using an IMA became a quality measure, nowadays I think there is a definite “intention to treat” with an IMA during CABG, if technically feasible.

Ryan: Was lack of IMA use a marker for surgeons with worse performance? How did you isolate the effect of the surgeon?

Hlatky: We were not able to examine individual surgeons and their use of IMAs. That’s the next step.

Ryan: Given your findings, are you or your group doing anything to improve IMA use?

Hlatky: Our study was more of a look back at a historical pattern of adoption, to gain some insight into the reasons for delayed adoption. Use of the IMA during CABG is now tracked, and there is relatively little room for improvement. Our study does suggest that surgical techniques may be adopted slowly, especially without an external push. Clinical trials are a major factor in spurring translation of findings into practice, and we have essentially no trials of IMA grafting.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

Share your observations about the use of IMA grafting at your institution.