August 11th, 2014

Study Offers Little Support for an Old Drug

Larry Husten, PHD

Digoxin is one of the oldest drugs in the cardiovascular arsenal, derived from the foxglove plant and first described in the 18th century by William Withering. It is frequently used in patients with heart failure (HF) and with atrial fibrillation (AF). The few trials supporting its use were performed in HF patients before newer treatments arrived. There have been no good trials in AF.

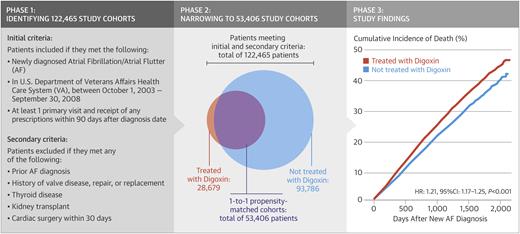

A new observational study published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology now provides the most detailed perspective on digoxin use in AF. Researchers examined data on more than 122,000 patients in the Veterans Affairs system who had newly diagnosed AF. During 350,000 patient-years of follow-up, roughly one-quarter of the patients died. Nearly 29,000 patients who received digoxin were matched with an equal number of controls who did not. The risk for death was higher among digoxin recipients than controls — a finding that remained significant after multivariable adjustment:

- Unadjusted hazard ratio for digoxin patients: 1.37 (CI 1.33-1.40, p<0.001)

- Multivariate adjustment: 1.26 (CI 1.23-1.29, p<0.001)

The authors acknowledged the limitations of observational studies but said that their sensitivity analyses suggested that any effect of unmeasured confounders would not likely have resulted in a major change in the findings.

Responding to a question from the editors of CardioExchange, the lead author of the study, Mintu Turakhia, recommended that clinicians use digoxin sparingly: “in light of the many other drugs that can be used for rate control, clinicians need to ask whether digoxin should be the treatment of choice for the patient in front of them when there are other, safer alternatives.”

In an accompanying editorial, Matthew Reynolds praises the study but argues that since digoxin for AF is more likely to be used in higher risk HF patients the “true” hazard ratio is likely to be lower than reported. Given the high rate of adverse events caused by the drug, he recommends that digoxin should only be used “selectively and with care in AF patients.” But, he concludes, “for now, there are still clinical circumstances (HF, difficult rate control, low blood pressure) where this old herbal remedy remains useful.”

CardioExchange Editor Harlan Krumholz said that “this study raises concerns about the safety of digoxin in the treatment of patients with AF. Given the range of medications available, any use of digoxin in this setting should require specific justification indicating why the benefits outweigh the potential risks. It’s time to pause on digoxin until studies can assure that it is providing a net benefit to these patients.”

Note: Comments on this news story are closed, but please join the discussion about this topic over at Harlan Krumholz’s interview with Mintu Turakhia, lead author of the TREAT-AF study.

August 7th, 2014

Neck Manipulation Linked to Cervical Dissection

Larry Husten, PHD

After a neck adjustment — also known as cervical manipulative therapy and typically employed by chiropractors and other healthcare providers — people are at increased risk for cervical dissections, which can lead to stroke, according to a scientific statement released by the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Although a cause-and-effect relationship is far from being proved, the groups say that healthcare providers should tell their patients about the association before starting the procedure.

“Most dissections involve some trauma, stretch or mechanical stress,” said José Biller, lead author of the scientific statement, in an AHA press release. “Sudden movements that can hyperextend or rotate the neck — such as whiplash, certain sports movements, or even violent coughing or vomiting — can result in CD, even if they are deemed inconsequential by the patient.”

Current knowledge about cervical dissection is limited to case-control studies and clinical reports, making it impossible to establish a cause-and-effect relationship. In some cases, an alternative explanation may be that patients in the early stage of cervical dissection may go to a chiropractor or other healthcare provider for relief of their neck pain.

“Although a cause-and-effect relationship between these therapies and CD has not been established and the risk is probably low, CD can result in serious neurological injury,” said Biller.

August 7th, 2014

Fellows: Want to Blog for CardioExchange at ESC.14?

Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, SM and John Ryan, MD

CardioExchange editors Harlan Krumholz and John Ryan are looking for fellows to blog for CardioExchange at the European Society of Cardiology Congresses from August 30th through September 3rd in Barcelona, Spain.

If you are interested in blogging, please contact us. We look forward to hearing from you!

August 7th, 2014

How Should We Evaluate Hospital Care?

Xiao Xu, PhD

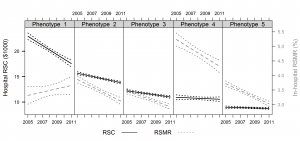

CardioExchange’s Harlan Krumholz asked Dr. Xiao Xu to discuss recent findings from her study of hospital differences in cost and clinical outcomes for heart failure treatment in a broad sample of hospitals. The study, “Phenotyping” Hospital Value of Care for Patients with Heart Failure, is published in Health Services Research, and the figure depicting the 5 distinct phenotypes is reprinted below. Each panel in the figure reflects one hospital phenotype—that is, a distinct group of hospitals that experience a unique pattern of risk-standardized cost (RSC) and risk-standardized mortality rate (RSMR) over time.

Reprinted from Xu X et al. “Phenotyping” Hospital Value of Care for Patients with Heart Failure. Health Services Research. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12197 © 2014 The Health Research and Educational Trust

As a health economist, I am certainly interested in ways to reduce health care costs, but I am more concerned about how we can slow the rising costs without adverse consequences to patients. This requires us to think about value—i.e., cost in the context of outcomes. Can we lower costs while improving—or at least maintaining—patient outcomes?

One approach is to look at our current system and try to understand who is achieving the best value and investigate how they are doing it. In our paper, we phenotype hospitals by the value of their care for patients with heart failure. In addition to cost, we look at mortality to see which hospitals achieve low mortality at low cost.

In this process, we notice some very interesting patterns. Some hospitals have similar mortality rates but very different costs, while others have similar costs but quite distinct mortality rates—and this is after accounting for how sick their patients are. What does this tell us? Hospitals vary considerably in how they turn inputs into outputs.

This provides a superb opportunity for hospitals to learn from each other. If all hospitals can emulate high-value hospitals—those with low mortality and low cost—we will save tremendous health care dollars as well as patients’ lives. A dual focus on both cost and patient health outcomes should be the new lens through which we see health care now.

August 5th, 2014

Large Analysis Supports Thrombolysis for Stroke

Larry Husten, PHD

Although thrombolysis for ischemic stroke has been widely recognized as beneficial, its use has been limited because of concerns about its effects in patients treated after 3 hours, in older patients, and in patients with mild and with severe strokes. Now a meta-analysis published in the Lancet offers evidence that the use of thrombolysis should be more aggressively pursued.

Researchers from the Stroke Thrombolysis Trialists’ Collaborative Group combined patient data from nine randomized trials testing alteplase against placebo or open control in 6756 patients. Thrombolysis was more likely to lead to a good stroke outcome, defined as no significant disability at 3 to 6 months, in patients treated within 4.5 hours:

- Treatment within 3 hours: 32.9% for alteplase versus 23.1% for control (OR 1.75, CI 1.35–2.27)

- Treatment between 3 and 4.5 hours: 35.3% versus 30.1% (OR 1.26, CI 1.05–1.51)

- Treatment after 4.5 hours: 32.6% versus 30.6% (OR 1.15, CI 0.95–1.40)

The chief disadvantage to thrombolysis was an early and significant increase in intracranial hemorrhage (fatal ICH at 1 week: 2.7% vs 0.4%). This resulted in a significant increase in early mortality, but this difference was no longer significant at 90 days, although a trend remained (17.9% versus 16.5%, HR 1.11, CI 0.99–1.25, p=0·07).

There were no significant variations in benefit and risk based on age or stroke severity. Despite the early increase in mortality, the authors concluded that thrombolysis was associated with an average absolute increase in disability-free survival of approximately 10% and 5% for patients treated within 3 hours and between 3 and 4.5 hours, respectively.

In an accompanying editorial, Michael Hill and Shelagh Coutts write that the finding of the meta-analysis is “definitive.” “The question now,” they write, “is not whether we can extend the window for treatment. Rather, how do we get everyone treated faster and how do we dispel preconceived notions about not treating older patients or those with milder strokes? We must move from the proven science to policy and systems of care.”

August 4th, 2014

Plant-Based Diet, Healthy Heart?

Kim Williams, MD and Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, SM

CardioExchange welcomes this guest post, which originally appeared on MedPage Today, from Kim Allan Williams, Chief of Cardiology at Rush University in Chicago and the next president of the American College of Cardiology. Kim explains why he went on a plant-based diet and now recommends the diet to patients, and answers questions from CardioExchange Editor Harlan Krumholz about his experience.

Physicians want to influence their patients to make lifestyle changes that will improve their health, but sometimes the roles are reversed and we are inspired by patients. It was a patient’s success reversing an alarming condition that motivated me to investigate a plant-based diet.

Just before the American College of Cardiology’s (ACC) annual meeting in 2003 I learned that my LDL cholesterol level was 170. It was clear that I needed to change something. Six months earlier, I had read a nuclear scan on a patient with very-high-risk findings — a severe three-vessel disease pattern of reversible ischemia.

The patient came back to the nuclear lab just before that 2003 ACC meeting. She had been following the Dean Ornish program for “Reversing Heart Disease,” which includes a plant-based diet, exercise, and meditation. She said that her chest pain had resolved in about six weeks, and her scan had become essentially normalized on this program.

When I got that LDL result, I looked up the details of the plant-based diet in Ornish’s publications — 1- and 5-year angiographic outcomes and marked improvement on PET perfusion scanning — relatively small numbers of patients, but outcomes that reached statistical significance.

I thought I had a healthy diet — no red meat, no fried foods, little dairy, just chicken breast and fish. But a simple Web search informed me that my chicken-breast meals had more cholesterol content (84 mg/100 g) than a pork chop (62 mg/100 g). So I changed that day to a cholesterol-free diet, using “meat substitutes” commonly available in stores and restaurants for protein. Within six weeks my LDL cholesterol level was down to 90.

I often discuss the benefits of adopting a plant-based diet with patients who have high cholesterol, diabetes, hypertension, or coronary artery disease. I encourage these patients to go to the grocery store and sample different plant-based versions of many of the basic foods they eat. For me, some of the items, such as almond milk or the chicken and egg substitutes, were actually better-tasting.

There are dozens of products to sample and there will obviously be some that you like and some that you don’t. One of my favorite sampling venues was the new Tiger Stadium (Comerica Park) in Detroit, where there are five vegan (nondairy vegetarian) items, including an Italian sausage that is hard to distinguish from real meat until you check your blood pressure — vegetable protein makes blood pressures fall.

In some parts of the country and some parts of the world, finding vegan restaurants can be a challenge. But in most places, it is pretty easy to find vegetarian-friendly options with a little local Web searching. Web searching can also help with the patients who are concerned about taste or missing their favorite foods. I often search with the patient for a substitute of something that they like, and quickly email suggestions back to them.

Interestingly, our ACC/American Heart Association (AHA) prevention guidelines do not specifically recommend a plant-based diet, as the studies supporting are very large and observational or small and randomized, such as those on Ornish’s whole-food, plant-based diet intervention reversing coronary artery stenoses. The data are very compelling, but larger randomized trials are needed to pass muster with our rigorous guideline methodology.

Wouldn’t it be a laudable goal of the ACC to put ourselves out of business within a generation or two? We have come a long way in prevention of cardiovascular disease, but we still have a long way to go. Improving our lifestyles with improved diet and exercise will help us get there.

Krumholz: Kim, this is a really interesting contribution. I am curious how you manage the plant-based diet during your travels. I have thought about this but often have less control over my food.

Williams: This diet does indeed require some planning, but “there’s an app for that!” Veg Out or Veggie Passport are two apps to check out. Using such tools to find restaurants has worked for us in Detroit, Melbourne, Rosario (Argentina), Paris, and even Chicago. However, airplane meals can be challenging — some have healthy eating in mind and some don’t. Knowing this in advance allows us to bring food when needed.

Krumholz: How do you ensure that you are getting the protein you need?

Williams: Protein is the easy part of a vegan diet, with soy and wheat proteins in so many meat and dairy substitutes that are widely available. However, as I mentioned, be careful of the blood-pressure falls with plant-based protein.

Krumholz: What do you do when you are unsure of how the food is prepared?

Williams: Learning about how the food is prepared really requires intense questioning of the chef. This is typically done through a wait staff person, who may or may not have a good database for such a discussion. If not, there are usually fresh vegetables available. When in doubt, I sometimes eat ahead of time and I generally keep nuts (protein, carbohydrates, and monounsaturated fat) handy for emergencies.

Krumholz: Are you promoting this strongly to your patients?

Williams: Yes, I am. But it is only part of a program of cardiac prevention. With younger people I discuss higher education, lifelong exercise habits, substance abuse, and diet, because they all relate to reducing cardiovascular mortality. A plant-based diet is only part of the overall picture.

Krumholz: What future studies are needed? Or do you feel we have enough evidence?

Williams: We really do need more evidence. Huge observational studies are available, particularly from Great Britain and Adventist Health Studies, but there is a relative lack of randomized evidence — yet, what it lacks in numbers it packs in consistency of effect. However, without more randomized evidence, the guideline writing committees will not consider making recommendations on this topic. Further, randomized trials could help uncover if the improvements in outcomes are actually due to the plant-based diet or other healthy lifestyle influences.

August 4th, 2014

Selections from Richard Lehman’s Literature Review: August 4th

Richard Lehman, BM, BCh, MRCGP

CardioExchange is pleased to reprint this selection from Dr. Richard Lehman’s weekly journal review blog at BMJ.com. Selected summaries are relevant to our audience, but we encourage members to engage with the entire blog.

JAMA Intern Med August 2014

Trends in Use of Ezetimibe After the ENHANCE Trial (OL): Once more it is time to praise Joe Ross. He has two articles waiting to see print in JAMA Internal. The first one tracks the continuing use of ezetimibe in the United States following the ENHANCE trial, which demonstrated that ezetimibe use lowered cholesterol levels, but did not slow the progression of atherosclerosis. He and his team looked at the records of 10 597 296 continuously eligible adults in the USA, and found that nearly three years after ezetimibe had been shown to do nothing, 186 272 of them were still ezetimibe users, i.e. 1.8% of the total adult population.

August 4th, 2014

Review Panel Exonerates The BMJ in Statin Kerfuffle

Larry Husten, PHD

An independent review panel has rejected a demand by a prominent researcher that The BMJ retract two controversial articles. The report largely exonerates the journal’s editors from any wrongdoing.

As previously reported, Rory Collins, a prominent researcher and head of the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration, had demanded that The BMJ retract two articles that were highly critical of statins. Although The BMJ issued a correction for both papers for inaccurately citing an earlier publication and therefore overstating the incidence of adverse effects of statins, this response did not satisfy Collins. He repeatedly demanded that the journal issue a full retraction of the articles, prompting The BMJ’s editor-in-chief, Fiona Godlee, to convene an outside panel of experts to review the problem.

The report of the independent statins review panel exonerates The BMJ from wrongdoing and said the controversial articles should not be retracted:

The panel were unanimous in their decision that the two papers do not meet any of the criteria for retraction. The error did not compromise the principal arguments being made in either of the papers. These arguments involve interpretations of available evidence and were deemed to be within the range of reasonable opinion among those who are debating the appropriate use of statins.”

In fact, the panel was critical of Collins for refusing to submit a published response to the articles:

The panel noted with concern that despite the Editor’s repeated requests that Rory Collins should put his criticisms in writing as a rapid response, a letter to the editor or as a stand-alone article, all his submissions were clearly marked ‘Not for Publication’. The panel considered this unlikely to promote open scientific dialogue in the tradition of the BMJ.”

The report did find some minor deficiencies in the editorial process at The BMJ and said that the delay from publication of the articles in October 2013 to the correction in May 2014 was too long. The panel said that the journal “should implement a significant event audit… to try and identify what would need to have been in place to ensure that the correction was made in a more timely fashion.”

They also stated that press releases should be used “cautiously” for opinion pieces about controversial topics.

The panel did not express an opinion about the risks and benefits of statins:

It is important to note that the panel has not been asked to pass judgment on the risks and benefits of statins per se, nor on the appropriate use of statin medication in low risk individuals. Instead the panel has been asked to decide whether there are sufficient grounds to require retraction of one or both of the articles from the scientific literature. The panel has been at pains not to take sides and not to support one view at the expense of another.”

Panel member Harlan Krumholz provided the following comment:

I had the privilege of serving with a remarkable set of experts who took the charge seriously and spent countless hours investigating the issue and deliberating over the recommendation. The panel did not weigh in on the issue of the risk of statins, but judged the merits of the call for retraction. In the end there was little doubt that the opinion pieces in The BMJ did not meet criteria for retraction and the correction that had been made was sufficient.”

August 1st, 2014

Noncardiac Surgery Guidelines Updated

Larry Husten, PHD

The reliability of current guidelines regarding perioperative evaluation and treatment of people undergoing noncardiac surgery has been seriously questioned because of a scandal discrediting Don Poldermans, a Dutch researcher widely published in the field. To address the current uncertainty, U.S. and European medical societies today released updated versions of these guidelines. The European guideline can be found here and the U.S. guideline can be found here.

“Given the recent publication of several large-scale trials, including POISE-II, and new risk calculators, as well as the controversy regarding the use of beta blockers related to the DECREASE trials, the writing committee felt it was necessary to reevaluate all of the data on cardiovascular care for the patient undergoing noncardiac surgery,” said U.S. Writing Committee Chair Lee Fleisher, in a press release.

Regarding beta-blockers, the subject of much of the controversy and concern, the U.S. and European guidelines now do not recommend routine use in patients who undergo non-cardiac surgery, though people who are already taking beta-blockers should continue taking them. (Previously the European guideline did support routine use of beta-blockers.) Both guidelines state that beta-blocker therapy may be initiated prior to surgery in carefully selected higher-risk patients.

Both the European and U.S. guidelines say that preoperative initiation of statin therapy may be considered in patients undergoing vascular surgery. People already taking statins should continue taking them.

August 1st, 2014

Do Doctors Need a Better Way to Take Notes?

John W McEvoy, MB BCh BAO and John Ryan, MD

CardioExchange’s John Ryan interviews Dr. John W. McEvoy regarding his recent perspective piece on the shortcomings of current electronic health record documentation published in The American Journal of Medicine. You can find the full text of his original article here.

Ryan: Why did you write this paper?

McEvoy: The short answer is that I wrote it out of frustration with the EHR. We had a roll out of Epic at our institution around the time and I was amazed at the poor job it does for documentation. Do not get me wrong, these systems have vast potential and I remain an EHR optimist; however, it was immediately clear to me that the user-interface and documentation functionality where not designed with the physician in mind. As I state in my paper and others have noted elsewhere, current EHR systems have been tailored to satisfy regulatory and billing needs, often leaving the physician out in the cold. It is an interesting dynamic from a marketing and business perspective. The buyers of EHR systems are not the actual users. Imagine a scenario where doctors were the ones who were actually buying this vastly expensive technology. I have absolutely no doubts that, in this hypothetical scenario, these systems would be more user-friendly and the documentation capacity much more clinically intuitive. However, the fact is that physicians are not the buyers of these systems. This leaves them lower down the priority list of EHR vendors, who instead have focused more on satisfying the regulatory, administrative, and billing needs of the real buyers (managed health systems, etc.).

Ryan: What are your solutions for a functional EHR?

McEvoy: There needs to be far greater focus on the needs of the user (physicians) and not just the buyers. I cannot think of a single physician who is satisfied with the EHR at our institution, and I understand that this is a widespread phenomenon. To me, this situation is untenable. To be honest, if I were an EHR vendor, I would be worried about my long-term future—or at least concerned enough to focus on this problem. Given the amount of discontent in the physician community, current vendors may be vulnerable to disruptive innovations and more user-friendly options from competitors. Thus, I think a real push by vendors to satisfy their actual users is now necessary (is this not customer service 101?). This will require real input from a range of physicians. I expect such efforts are already well underway. Physicians may need to advocate more too. I am not an informaticist, so I will not try to tackle the technological challenges around documentation here. However, I do cite some prior efforts and other ideas in my paper for readers who are interested in this.

I think the take home message is that if EHR vendors were selling this to physicians, I can guarantee that they would do a better job with interface and documentation—the market would demand it. I believe the technology is available, right now, to make this better. However, to me, the motivation does not seem to be there for vendors. Thus, maybe the best idea of all would be to give actual clinicians more meaningful input into purchasing and renewal decisions (and contracts agreements) between health systems and EHR vendors.

Ryan: I often feel that we think fondly of the notes we wrote before EHR, but you know from our work in Ireland that, more often than not, those notes were pretty substandard (and short too), with minimal detail and legibility. How do you think the value of the note has changed in the past ten years since EHR became more widespread? Is it a symptom of EHR or is it just a feature of increasing clinical demands and emphasis on billing?

McEvoy: Sure, written notes were not perfect, and many of the deficits of written note-taking are overcome in the current EHR (for example, legibility is vastly improved and decision support is helpful). However, just because the old era of written note-taking was no better should not mean we should be satisfied with the current state of affairs. In some respects, the major problem with current EHRs is on the opposite end of the spectrum to written notes. I struggle with the vast quantity of information in current notes, the poor signal to noise ratio, and (most concerning to me) the lack of a meaningful clinical narrative for the reader. I think the this difficulty separating noise from important information interrupts the narrative flow of many notes, ending up in physicians losing interest and scanning ahead. I worry about the information that is thereby lost, and the clinical consequences of this loss, as physicians try to reconstruct the narrative from many EHR-based notes. I would be interested to hear the perspectives of other CardioExchange readers.

Ryan: Do all your papers now come with an analogy from the world of physics—first Schrodinger, now Turing…?

McEvoy: Mainly just in commentaries and opinion pieces, not my original research. I am no expert, but I do read widely and enjoy keeping abreast of other fields of science. I find it satisfying to think of how problems (and their solutions) from these varied fields may apply to medicine.