February 18th, 2011

A Case of Clopidogrel Nonresponsiveness?

Tariq Ahmad, MD, MPH and James Fang, MD

This latest installment in our case discussion series is submitted by Tariq Ahmad, MD, MPH. We encourage members to submit cases that they believe warrant discussion. Selected cases will be presented to the community, and case authors will receive a $100 Amazon gift card.

A 70-year-old woman presents to the ED with an anterior STEMI. She had a stroke 3 months prior and an MI 5 months prior to that, with DES to the LAD. She is morbidly obese and has hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and peripheral artery disease with bilateral carotid stenosis. Soon after arriving in the ED, she goes into cardiac arrest and is found to be in ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation. After a 15-minute resuscitation that includes intubation, she is taken to the catheterization lab, where a thrombus is found in her LAD stent. She undergoes PCI with a BMS to the LAD. During the procedure, she has significant hemodynamic instability and requires an intra-aortic balloon pump. She is admitted to the CCU for further management.

According to her family, she has been adherent to her clopidogrel. A VerifyNow P2Y12 platelet function test shows 0% P2Y12 inhibition.

Questions:

- Do you feel fairly confident, based on the VerifyNow test, that this patient is a clopidogrel nonresponder?

- Would you perform any additional testing to assess whether she is a clopidogrel nonresponder?

- Would you increase the clopidogrel dose or give an alternate agent?

Response

The most common cause of clopidogrel “resistance” (and for that matter, aspirin “resistance”) remains noncompliance. The “0%” P2Y12 inhibition with VerifyNow is highly suspicious for noncompliance despite the report from the patient’s family. I am not confident that she is a clopidogrel nonresponder. I would recommend that she be given clopidogrel in the CCU and have her platelet reactivity retested in 48 hours.

If the test demonstrates nonresponsiveness, then I would consider using prasugrel despite the risks, which would need to be reviewed with the patient and family. The issue of increased intracerebral bleeding is not trivial with prasugrel (e.g., age, prior stroke). To further minimize risk, the duration of therapy with prasugrel could be limited since a bare metal stent was used. Another option is clopidogrel at 150 mg daily, although the findings of GRAVITAS and OASIS-7 make this choice less than ideal. Ticagrelor will soon be available as another option. Some would consider adding cilostazol. Finally, it should be kept in mind that stent thrombosis is not just an issue of P2Y12 inhibition; there are patient- and procedural-related factors, as well.

The issue of routine assessment of platelet function after PCI is evolving and is not yet the standard of care. The “negative” results of GRAVITAS and OASIS-7 have made this issue even more complicated, however, this may be more of an indictment of clopidogrel rather than the concept of measuring platelet reactivity.

Which platelet assay to use? VerifyNow has the greatest clinical data available in human studies, however, both VerifyNow and PlateWorks have good discriminating ability for important clinical endpoints and both are relatively easy to use at the bedside. The POPULAR study (JAMA 2010; 303:754) is worth reviewing in this regard.

February 17th, 2011

Quarter of U.S. Adults 45 and Older Taking Statins

Larry Husten, PHD

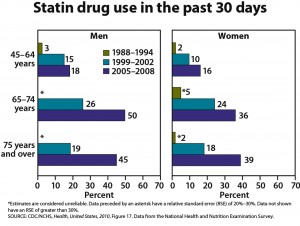

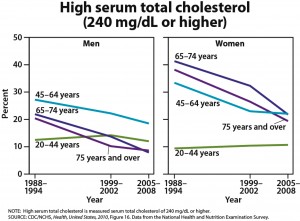

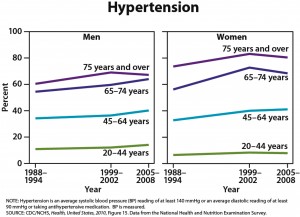

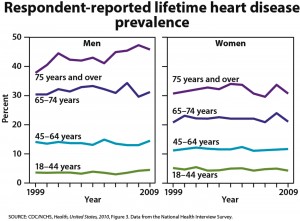

One-quarter of U.S. adults age 45 and older are taking statins, and one-half of men ages 65 to 74 are taking these drugs, according to the CDC’s annual report on trends in health statistics. From 1988 to 1994, only 2% of adults age 45 and older were taking statins. High cholesterol levels have been declining, according to the CDC, but hypertension, diabetes, and obesity have all increased. The overall prevalence of heart disease has remained stable in all groups except for an increased rate in men age 75 and older.

An article in Medpage Today includes comments from Christopher Cannon, James Stein, Robert Califf, and Harlan Krumholz.

February 17th, 2011

Unreasonable Expectations for Quality Improvement

John E Brush, MD

At a recent committee meeting, my hospital’s administration announced new quality measures and targets. Striving for top performance, the board of the hospital system set the bar extraordinarily high. The bonuses of senior management are tied to achieving the targets, so the announcement had everyone’s attention.

One target that caught my interest was for achieving a door-to-balloon time of less than 90 minutes in STEMI patients. As an interventional cardiologist who helped to organize the national D2B Alliance for Quality, I have spent some time thinking about door-to-balloon times. The hospital set the target of less than 90 minutes at 96%. I pointed out that this was unreasonable, but I was told that the number came from a payer’s pay-for-performance program and from the board.

If we are going to use statistics to determine pay and recognition, it is important to use the statistics correctly. A quality target is an estimate, and because of random effects that have nothing to do with quality, there is a confidence interval around that estimate that should be factored into the cutoff value. The random effects have different implications for the payer than they do for the payee. If a hospital gets close to the target but falls short of the cutoff, the payer receives effort for quality but pays nothing — not bad. For the payee, however, falling short of the cutoff means putting forth effort and receiving absolutely nothing for it — a demoralizing outcome to say the least. The randomness around the cutoff value is a bad, all-or-nothing bet for the payee but not for the payer. So, setting a reasonable target that accounts for random effects is an important consideration as you attempt to engage the people who actually do the work of achieving quality — and to keep them engaged.

Small numbers at individual hospitals can amplify these random effects. Of the STEMI alerts that are called, some will be for patients who have insignificant lesions or small vessels and who, therefore, do not undergo intervention. Some will have surgical disease. Others will be excluded from the statistics for a variety of reasons such as the need for intubation or a balloon pump. After all of those exclusions, the number of primary STEMI patients at a typical hospital may be around 40 per year. (Regionalization of STEMI care could increase that number, but that is topic for a different commentary.) So with 40 patients per year, if you have a door-to-balloon time of 91 minutes for 2 patients, you fail to reach a target of 96%. Enormous effort could go into creating a first-rate program, all for naught.

But these are really sick patients, you say. Why not set a high bar and intensify efforts? Why not 100%? Because achieving consistent 100% performance is impossible for any hospital. There is too much ambiguity in making the diagnosis. A patient can wander up to the triage desk of your emergency room complaining of back or abdominal pain, then sit for an hour before being brought back to the treatment area, and 30 minutes later, an ECG could show a STEMI. Or a patient with atypical symptoms could have an ECG that is ambiguous, due to left-ventricular hypertrophy or other artifacts. Despite the very best efforts of good caregivers, the diagnosis of some STEMI patients is occasionally delayed. But when we try to explain these difficulties to non-medical administrators, we are often accused of making excuses. Clinical ambiguity is not an excuse — it is an inescapable part of practicing medicine.

Setting an unreasonably high bar can have unintended side effects. One is to create a “hair trigger” for calling STEMI alerts. Hastily rushing patients with ambiguous clinical findings to the lab could be unsafe if the diagnosis is an aortic dissection, pulmonary embolus, or any number of other diagnoses that can sometimes mimic a STEMI. Excessive false-positive STEMI alerts also can erode the staff’s dedication and engagement, which are necessary to maintain a well-functioning system of care. Finally, there are opportunity costs when we apply excessive resources to chase after impossible statistical goals and neglect other areas of need for quality improvement.

Reliable care for STEMI patients remains an important goal. We should indeed set high standards. But we should not set unachievable goals that ignore the play of chance and clinical ambiguity. If we want to create new quality-improvement challenges, we can define new measures, or use composite measures, or all-or-nothing measures, or outcome measures. But ratcheting up the cutoffs to unachievable levels for individual targets is statistically unjustified and should be avoided.

February 15th, 2011

Study Sheds Light on Racial Disparities in Hospital Readmissions

Larry Husten, PHD

Although many studies in recent years have explored the issue of racial disparities in health care, a new study scrutinizes the effect of race on hospital readmissions, an area that has not been previously examined. In a report appearing in JAMA, Karen Joynt and colleagues examined Medicare data to study readmissions after hospitalizations for acute MI, congestive heart failure, and pneumonia.

Readmission rates were higher for black patients than for white patients (24.8% vs 22.6%) and were higher for patients receiving treatment at hospitals categorized as minority-serving (i.e., treating the largest percentage of minority patients) than for those at non-minority-serving hospitals (25.5% vs 22.0%). Here are the readmission rates for acute MI, based on both race and site of care:

- White/Non-minority-serving hospital: 20.9%

- Black/Non-minority-serving hospital: 23.3%

- White/Minority-serving hospital: 24.6%

- Black/Minority-serving hospital: 26.4%

The authors concluded that their “findings that racial disparities in readmissions are related to both patient race and the site where care is provided should spur clinical leaders and policy makers to find new ways to reduce disparities in this important health outcome.”

In an accompanying editorial, Adrian Hernandez and Lesley Curtis discuss the “unintended consequences” of “financial incentives based on readmission rates” that “may unfairly penalize minority-serving hospitals and thereby widen the gap in care for disadvantaged minorities.”

February 15th, 2011

Dabigatran for Patients with AFib: Putting the Updated Recs into Practice

Samuel Goldhaber, MD

CardioExchange welcomes Samuel Zachary Goldhaber, MD, Director of the Venous Thromboembolism Research Group and Medical Co-Director of the Anticoagulation Management Service at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He answers practical questions from the CardioExchange editors about newly updated recommendations on the use of dabigatran in patients with atrial fibrillation, issued by the American College of Cardiology Foundation, the American Heart Association, and the Heart Rhythm Society.

Before pursuing elective cardioversion, should a patient be maintained on dabigatran for 3 weeks, or has the optimal duration changed? If the cardioversion succeeds, should the treatment last an additional 3 weeks after the procedure?

The guidelines remain the same for anticoagulation with planned elective cardioversion: 3 weeks of therapeutic anticoagulation before the procedure and at least 4 weeks of therapeutic anticoagulation after sinus rhythm has been achieved (Chest 2008; 133:546S). Dabigatran becomes therapeutic within 2 hours of administration.

For a patient with new-onset atrial fibrillation, does intravenous heparin have any role as a bridge to dabigatran?

When an asymptomatic patient presents with new-onset atrial fibrillation in the office setting, oral anticoagulation with dabigatran can be started without intravenous heparin. If the patient with new-onset atrial fibrillation is symptomatic, cardioversion may need to be performed imminently (if no thrombus is visualized on transesophageal echocardiography). In the symptomatic patient, there are two options:

- Begin therapy with intravenous heparin. (Cardioversion has not been extensively studied using dabigatran alone in patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation.)

- Begin therapy with dabigatran but without using intravenous heparin. (In the largest cardioversion experience to date, the stroke rate was low in dabigatran recipients, especially if they had been “cleared” first by transesophageal echocardiography; Circulation 2011; 123:131.)

How should a patient be transitioned on and off dabigatran from other antithrombotic agents (e.g., warfarin, enoxaparin, dalteparin, heparin)?

For patients switching from warfarin to dabigatran, give the first dose of dabigatran after the INR has declined to less than 2.0. In practice, this usually means withholding one or two doses of warfarin. For patients receiving parenteral subcutaneous anticoagulation, give the first dose of dabigatran just before the next scheduled injection of parenteral anticoagulation. For patients receiving intravenous heparin, give the first dose of dabigatran about 2 hours after discontinuing intravenous heparin.

If the patient experiences a bleeding complication while on dabigatran, is an antidote available?

There is no specific antidote for dabigatran-related bleeding. General supportive care and “tincture of time” usually work. In extreme circumstances, when confronted with a major, life-threatening hemorrhage, consider using recombinant factor VIIa or emergency hemodialysis.

If a patient has recurrent thromboembolic events while on dabigatran, what test should be performed to monitor the drug’s efficacy? Should a change in treatment be considered?

There is no clinically available test (such as INR, aPTT, or anti-factor Xa level) to monitor dabigatran’s efficacy. If a patient suffers a recurrent thromboembolic event, take a careful history to determine whether one or more doses of dabigatran were omitted. Dabigatran has a short half-life. If medication adherence was perfect, consider switching to another anticoagulation regimen.

For more of our coverage on dabigatran, check out the Dabigatran Resource Round-Up.

February 15th, 2011

AHA Releases Updated Guidelines for the Prevention of CV Disease in Women

Larry Husten, PHD

Newly published online in Circulation, updated AHA guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women emphasize practical medical advice. “These recommendations underscore the fact that benefits of preventive measures seen day-to-day in doctors’ offices often fall short of those reported for patients in research settings,” said Lori Mosca, chair of the guidelines writing committee, in an AHA press release. “Many women seen in provider practices are older, sicker, and experience more side effects than patients in research studies. Factors such as poverty, low literacy level, psychiatric illness, poor English skills, and vision and hearing problems can also challenge clinicians trying to improve their patients’ cardiovascular health.” The guidelines state that some once-common therapies are not effective and may be harmful when used for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women, including:

- Hormone therapy and selective estrogen-receptor modulators (SERMSs)

- Antioxidant supplements

- Folic acid

- Routine use of aspirin to prevent MI in women <65

The guidelines incorporate information about lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and pregnancy complications in the evaluation of risk in women. “These have not traditionally been top of mind as risk factors for heart disease,” said Mosca in the press release.

The document also incorporates the impact of racial and ethnic diversity on cardiovascular disease in women, including the significant impact of hypertension in African-American women and diabetes in Hispanic women.

February 14th, 2011

CRT Found Beneficial in Less Severe Heart-Failure Patients

Larry Husten, PHD

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) appears to be beneficial in patients with less severe heart failure (NYHA class I and II), according to a new systematic review published online in Annals of Internal Medicine. In a previous analysis, Nawaf Al-Majed and colleagues had found that CRT was highly beneficial in HF patients with NYHA class III and IV symptoms. The new analysis incorporates the results of recent trials, including less symptomatic HF patients.

The investigators analyzed data from 25 trials including 9082 patients and found a significant reduction in all-cause mortality and rehospitalizations for HF in NYHA class I and II patients. However, functional outcomes or quality of life did not improve in this group. The relative magnitude of the benefit was similar to that observed in patients with more severe HF.

The authors conclude that their data “supports the expansion of indications for CRT to incorporate less symptomatic patients with HF who have LVEF <30%, QRS duration >120 msec, and are in sinus rhythm.” They estimate that CRT “may well be indicated now for most of the 40% of individuals with systolic HF who have QRS exceeding 120 msec” but acknowledge that eligibility criteria derived from randomized controlled trials is “clearly imperfect.”

February 14th, 2011

AF Guidelines Updated to Incorporate Dabigatran

Larry Husten, PHD

Less than two months after the publication of the 2010 updated atrial fibrillation (AF) guidelines, the AHA, the ACC, and the HRS have released a new focused update incorporating recommendations and a discussion concerning the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran, which gains a Class I recommendation:

Class I: Dabigatran is useful as an alternative to warfarin for the prevention of stroke and systemic thromboembolism in patients with paroxysmal to permanent AF and risk factors for stroke or systemic embolization who do not have a prosthetic heart valve or hemodynamically significant valve disease, severe renal failure (creatinine clearance 15 mL/min), or advanced liver disease (impaired baseline clotting function). (Level of Evidence: B)

The update does not recommend routinely switching patients to dabigatran who are already successfully taking warfarin:

Because of the twice-daily dosing and greater risk of nonhemorrhagic side effects with dabigatran, patients already taking warfarin with excellent INR control may have little to gain by switching to dabigatran.

Here is the discussion about choosing between dabigatran and warfarin:

Selection of patients with AF and at least 1 additional risk factor for stroke who could benefit from treatment with dabigatran as opposed to warfarin should consider individual clinical features, including the ability to comply with twice-daily dosing, availability of an anticoagulation management program to sustain routine monitoring of INR, patient preferences, cost, and other factors.