September 13th, 2012

Meta-Analysis Links Stress at Work and Heart Disease

Larry Husten, PHD

A new study in the Lancet provides the best evidence yet that work-related stress and, in particular, job strain — “the combination of high job demands and low control at work” — plays a small but important role in causing heart disease. In order to address the limitations of previous studies on this topic, including a publication bias which might exaggerate the effect, European investigators performed a large collaborative meta-analysis of published and unpublished studies.

The IPD-Work (individual-participant-data meta-analysis in working populations) consortium found that 15% of nearly 200,000 individuals reported having job strain. With a mean follow-up of 7.5 years, job strain was significantly associated with increased risk for heart disease. The effect was higher in published studies, though it still achieved significance in the unpublished studies:

- Overall hazard ratio (HR) for job strain: 1.23,CI 1.10–1.37

- HR in published studies: 1.43, CI 1.15−1.77

- HR in unpublished studies: 1.16, CI 1.02−1.32

The investigators calculated that the population attributable risk for job strain was 3.4%, which, they noted, was substantially lower than the major risk factors of smoking, obesity, and physical inactivity.

“Our findings suggest that job strain is associated with a small, but consistent, increased risk of an incident event of cardiovascular heart disease,” they concluded.

In an accompanying comment, Bo Netterstrøm writes that “job strain is a measure of only part of a psychosocially damaging work environment, which implies that prevention of workplace stress could reduce incidence of coronary heart disease to a greater extent than stated in the authors’ interpretation of the calculated population-attributable risk for job strain.”

September 13th, 2012

A Manhattan Project to End the Obesity Epidemic

Larry Husten, PHD

A newly launched nonprofit organization, the Nutrition Science Initiative, will try to find an answer to the question, “What should we eat to be healthy?” Called NuSI (pronounced “new see”) for short, the organization is nothing if not ambitious: its goal is to seek “the end of fad diets and high obesity rates.”

![]() NuSI’s founders are Gary Taubes and Peter Attia. Taubes is the science journalist who helped launch the low-carb diet resurgence with his controversial New York Times magazine articles and subsequent books, Good Calories, Bad Calories and Why We Get Fat. Attia, who is the President of NuSI, trained in surgery at Johns Hopkins and the NIH before working as a consultant at McKinsey & Company.

NuSI’s founders are Gary Taubes and Peter Attia. Taubes is the science journalist who helped launch the low-carb diet resurgence with his controversial New York Times magazine articles and subsequent books, Good Calories, Bad Calories and Why We Get Fat. Attia, who is the President of NuSI, trained in surgery at Johns Hopkins and the NIH before working as a consultant at McKinsey & Company.

Taubes explains the premise of NuSI:

NuSI was founded on the premise that the reason we are beset today by epidemics of obesity and type 2 diabetes, and the reason physicians and researchers think these diseases are so recalcitrant to dietary therapies, is because of our flawed understanding of their causes. We believe that with a concerted effort and the best possible science, this problem can be fixed.

NuSI originally started as a more modest endeavor, but has now received a significant commitment of financial support from a foundation started by billionaire hedge fund manager John Arnold. The aim of the organization, as the following NuSI publicity slide states, is to “create a Manhattan Project-like effort to solve” the problem of obesity in the U.S.:

The NuSI scientific advisory board is composed of Alan Sniderman, a lipid researcher at McGill University; David Harlan, the former head of the Diabetes, Endocrinology, & Metabolic Diseases branch of the NIDDK and now at the University of Massachusetts; Mitchel Lazar, of the University of Pennsylvania; and Kevin Schulman, of Duke University.

On his Weighty Matters blog, obesity clinician and writer Yoni Freedhoff offers a perspective both critical and supportive of the NuSI agenda.

September 12th, 2012

Study Predicts Renal Denervation Will Be Cost-Effective in Resistant Hypertension

Larry Husten, PHD

Renal denervation (RDN) for resistant hypertension may be cost-effective and may provide long-term clinical benefits, according to a new analysis published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Benjamin Geisler and colleagues developed a model to predict the impact of the Medtronic Symplicity RDN system in patients with resistant hypertension. Over 10 years, according to the model, RDN treatment resulted in large differences in outcomes, though the benefits were less pronounced when projected over a lifetime.

Projected 10-Year Relative Risk:

- Stroke: 0.70 (reduced from 11.6% in the control group to 8.2% in the RDN group)

- MI: 0.68 (reduced from 9.6% to 6.5%)

- CHD: 0.78 (reduced from 24.8% to 19.4%)

- HF: 0.79 (reduced from 5.4% to 4.3%)

- ESRD: 0.72 (reduced from 2.9% to 2.1%)

- CV mortality: 0.70 (reduced from 12.5% to 8.7%)

- All-cause mortality: 0.85 (reduced from 23.0% to 19.5%)

Median survival was lengthened from 17.07 years to 18.37 years. The authors calculated an increase in quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) from 12.07 to 13.17 years, resulting in a discounted incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $3071/QALY. Cost-effectiveness was “markedly below the commonly accepted threshold of $50,000 per QALY,” and might even be cost-saving, according to the authors.

The model assumes that RDN causes a long-term reduction in blood pressure, though current data from the Symplicity HTN-2 trial only extend to 36 months. However, the authors reported that RDN remained “cost-effective across a wide range of assumptions.”

September 11th, 2012

Advertising That Falls Short — Part 1: Omega-3 Fatty-Acid Supplements

Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, SM

Lately I’ve been pondering the impact of advertisements on the public’s knowledge, and I’ve decided to start a series of posts about some that trouble me.

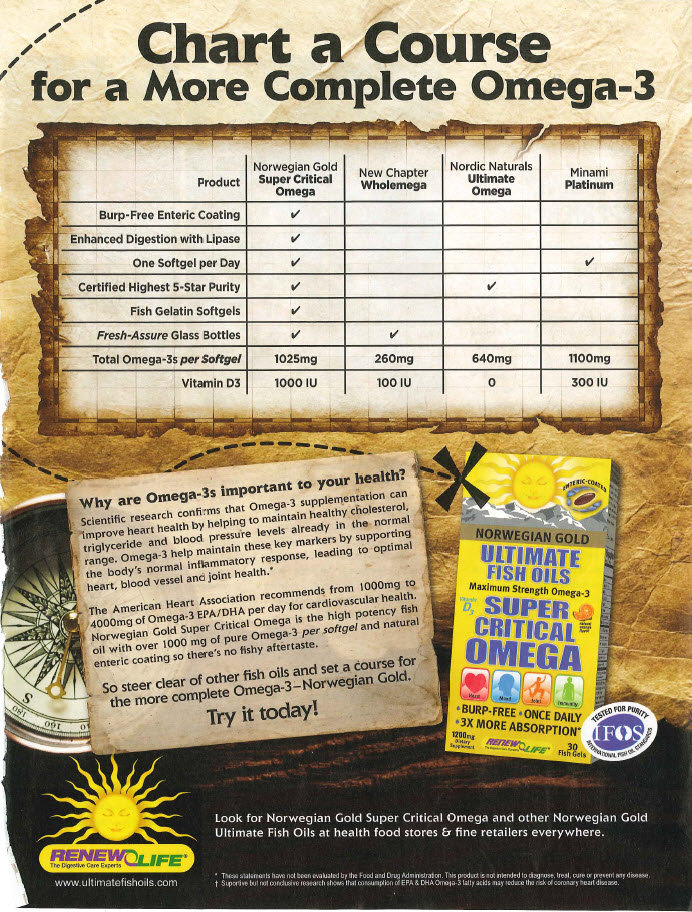

This week JAMA published a meta-analysis showing a lack of evidence that omega-3 fatty-acid supplements reduce the risk for heart disease (confirming an Archives of Internal Medicine meta-analysis from earlier this year). The ad below, created by a company called RenewLife, appears in the October 2012 issue of Yoga magazine.

The ad’s purported focus is to explain why omega-3 fatty acids are important to your heart health — specifically, according to the ad, that they help to maintain “healthy cholesterol, triglyceride, and blood pressure levels already in the normal range. Omega-3 helps maintain these key markers by supporting the body’s normal inflammatory response, leading to optimal heart, blood vessel, and joint health.”

What’s lacking in this message is that these supplements do not improve patient outcomes. The ad does refer to an American Heart Association recommendation from 2003: “For patients with documented CHD, the AHA recommends ≈1 g of EPA and DHA (combined) per day” — with an emphasis on dietary intake.

However, outcomes trials of omega-3 supplements have, overall, failed to show a benefit in preventing heart disease. The possible reasons for that failure are many, and future research might identify an effective dose and formulation. But, for now, a lack of proven benefit is the state of the trial evidence — and that is the message that the public should hear.

What is our role as clinicians in putting ads like this in context for patients?

September 11th, 2012

More Evidence That Omega-3 Supplements Don’t Work

Larry Husten, PHD

Once again researchers have failed to find any clinical benefit for omega-3 supplements. In a new meta-analysis and systematic review published in JAMA, Evangelos Rizos and colleagues analyzed 20 randomized controlled trials including 68,680 patients and found no significant effect on any of the endpoints:

- all-cause mortality: relative risk (RR) 0.96, CI 0.91 – 1.02

- cardiac death: RR 0.91, CI 0.85 – 0.98 (not significant after correction for multiple comparisons)

- sudden death: RR 0.87, CI 0.75 – 1.01

- MI: RR 0.89, CI 0.76 – 1.04

- stroke: RR 1.05, CI 0.93 – 1.18

The authors report that they found no evidence supporting a beneficial effect related to either lowering triglycerides or reducing sudden death. Regarding triglycerides, they write, “the proposed protective role of omega-3 PUFAs by lowering triglyceride levels is not supported by our study, because our findings do not support an advantage of higher (triglyceride-lowering) doses compared with lower doses of omega-3.” In addition, no benefit was found in preventing sudden death, “thus rejecting a distinct antiarrhythmic mediated omega-3 PUFA effect,” although the authors acknowledge that the evidence was “underpowered to detect a small underlying effect.”

Although early studies suggested a benefit for omega-3 supplements, the accumulation of evidence has resulted in a consistent failure to confirm this benefit, according to the authors. Current evidence, they conclude, does “not justify the use of omega-3 as a structured intervention in everyday clinical practice or guidelines supporting dietary omega-3 PUFA administration.”

September 11th, 2012

Updated Rhythm Device Guidelines Clarify and Expand CRT Criteria

Larry Husten, PHD

A newly released update of 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac arrhythmias contains some much-needed clarification about indications for cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT). The document was developed jointly by the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the Heart Rhythm Society.

Highlights of the documents include:

- The Class 1 recommendation for CRT for patients with systolic heart failure (HF) is now limited to patients with a QRS duration of at least 150 ms but has been expanded to include both patients with NYHA class II symptoms and LBBB patients.

- A Class IIa recommendation for patients with a QRS duration of 120-149 who otherwise meet the criteria for a Class 1 recommendation.

- A new Class IIB recommendation for patients with NYHA class I symptoms with LVEF 30% or lower, ischemic HF, sinus rhythm, and LBBB with a QRS duration at least 150 ms.

- Recommendations from 2008 remain in effect for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, arrhythmogenic RV dysplasia/cardiomyopathy, genetic arrhythmias, congenital disease, primary electrical disease, and terminal care.

The document also provides updated information about remote follow-up and monitoring of patients with cardiovascular implantable electronic devices.

“There is growing evidence that patients with the widest, most abnormal looking ECG potentially benefit most compared to patients whose ECG are less abnormal,” said Cynthia M. Tracy, the chair of the writing group, in a press release. She noted that patients with LBBB particularly benefit from CRT.

The authors noted that a separate document under development will define appropriate use criteria and “will help to further interpret the best science and apply it to various clinical scenarios.”

September 10th, 2012

Antihypertensive Use Among Pregnant Women on the Rise

Larry Husten, PHD

Growing numbers of pregnant women are taking antihypertensive drugs that may harm themselves or their babies, according to a new study published in Hypertension.

Brian Bateman and colleagues analyzed Medicaid data on more than 1.1 million pregnant women from 2000 to 2007. Overall, 4.4% of the women received antihypertensive medications at some point during their pregnancy. During the study period, the use of antihypertensive drugs increased from 3.5% to 4.9%. This increase, according to the authors, is “consistent with the rising rates of chronic hypertension and gestational hypertension… which in turn may reflect rising rates of obesity and advanced maternal age in US parturients.”

Exposure to antihypertensive drugs occurred in 1.9% of women during the first trimester, 1.7% during the second trimester, and 3.2% during the third trimester. ACE inhibitors, which are contraindicated in late pregnancy, were used by 4.9% of antihypertensive users in the second trimester and 1.1% in the third. The authors said that automatic refills and the “prescribing physicians’ failure to ask about the possibility of pregnancy are two plausible explanations.”

About one half to two thirds of women who had been taking antihypertensive drugs prior to their pregnancy discontinued treatment during the first or second trimester. According to the authors, although antihypertensive therapy for mild-to-moderate hypertension can prevent progression to severe hypertension, it is unknown whether it can reduce the risk for pregnancy complications, including placental abruption, fetal demise, superimposed preeclampsia, preterm birth, or maternal morbidity.

“While we know high blood pressure, or hypertension, occurs in about 6 percent to 8 percent of all pregnancies, we know little about how women and their doctors treat the condition,” said Bateman, in an AHA press release.

The authors pointed out that “there is virtually no data on the comparative effectiveness and safety of the different treatment options for hypertension” in pregnant women. They concluded: “Research investigating the comparative safety and efficacy of antihypertensive therapy in pregnancy is urgently needed to define the optimal approach to therapy.”

September 10th, 2012

Selections from Richard Lehman’s Literature Review: September 10th

Richard Lehman, BM, BCh, MRCGP

CardioExchange is pleased to reprint selections from Dr. Richard Lehman’s weekly journal review blog at BMJ.com. Selected summaries are relevant to our audience, but we encourage members to engage with the entire blog.

JAMA 5 Sep 2012 Vol 308

The FDA and the Safety Risks of Innovation (pg. 869): Cancer, multiple sclerosis, stroke: do you want your patients to get the benefit of new drugs for these conditions as soon as possible? It’s pretty hard to say no to a question like that, but if you follow the flow of this rhetoric you can easily ignore poor evidence of benefit, and absence of evidence of safety. That’s what the authors of this short piece demonstrate in relation to vandetanib for medullary thyroid cancer, fingolimod for MS, and dabigatran for stroke prevention in AF. For all these drugs, the US Food and Drug Administration used its expedited approval program, as it did for 46% of the new drugs which came before it in 2011. All of them are expensive and in each of these three cases there are clear signals of harm: but they have been let loose on patients simply on condition that there will be post-marketing studies. The same happens in the UK, and we are about to lose what small protection NICE once offered, since now any manufacturer will be able to appeal against rejection and have a NICE decision overturned by an “independent” assessor picked by the Department of Health. This ridiculous travesty of proper regulation shows that nothing has been learnt from the lessons of Vioxx or Avandia. Pre-order your copy of Ben Goldacre’s Bad Pharma now.

Aortic Stiffness in the Elderly (pg. 875): Framingham is a town which is getting swallowed in the urban sprawl to the west of Boston, Massachusetts, and if you are very clever at negotiating its northern outskirts you will find yourself in wonderful woodland garden containing many gems of the spring season, especially trilliums. Oops, I digress. This is meant to be about the latest from the Framingham Heart Study, not Plant of the Week. Start again: if you want the best source of knowledge about the wild flowers of New England, or about the natural history of cardiovascular disease in a mainly white population since 1948, turn to Framingham. The Framingham Heart Study has generated about 2,400 papers since 1950, and if you piece them all together… well, you may be dead before you’re finished, like most of the original cohort. This latest paper explores the important question of aortic stiffness in the elderly: important because it is a predictor of total mortality and especially of heart failure without systolic dysfunction. The surprise for me here was that previous hypertension was not associated with late arterial stiffening. So it just seems to happen.

CMR to Detect MI in Older Adults (pg. 890): It’s one thing to recruit several thousand people in a Massachusetts town with a large Italian population, but just imagine if you had a few hundred thousand people inhabiting an island which few of them want to leave, descended mostly from the same few 1,000-year-old families. You could capture the entire population genome (this happened years ago) and do all the epidemiology you liked. ICELAND-MI does what it says on the side of the trawler: it looked for cardiac MRI (CMR) evidence of myocardial infarction in 936 participants aged 67 to 93 years, including 670 who were randomly selected and 266 with diabetes. Previously undetected MI showing up on CMR is about 60% commoner than recognized MI, and carries about the same prognosis. These sons and dottirs should all be on the standard post-MI drug cocktail.

September 7th, 2012

News Briefs: Cholesterol Trends, AHA Late-Breakers, FDA Updates On Rivaroxaban And Heartware HVAD

Larry Husten, PHD

Cholesterol Trends

The Centers for Disease Control issued a new report with the latest details about the prevalence of cholesterol screening and high blood cholesterol in U.S. adults. Here is their summary of the key findings:

…cholesterol screening increased from 72.7% in 2005 to 76.0% in 2009, whereas the percentage of those screened who reported being told they had high cholesterol increased from 33.2% to 35.0%. Previously identified demographic disparities persist.

AHA Previews LBCTs

The American Heart Association has published a preview of the late-breaking clinical trials scheduled for presentation in November at the scientific sessions in Los Angeles. Twenty-eight LBCTs have been selected, including the NIH’s FREEDOM (Future REvascularization Evaluation in patients with Diabetes mellitus: Optimal management of Multivessel disease) trial and the controversial Trial to Assess Chelation Therapy (TACT).

J&J Provides More Information to FDA About Rivaroxaban

Johnson & Johnson said today that it had fully responded to the FDA’s request for more information about the use of rivaroxaban (Xarelto) in patients with acute coronary syndromes. The company also said it had resubmitted its supplemental New Drug Application (sNDA) for the drug to reduce the risk of stent thrombosis in ACS patients.

Heartware HVAD Close to FDA Approval

The Heartware HVAD ventricular assist system may be approved soon by the FDA, according to Wells Fargo analyst Larry Biegelsen. Robert Kormos, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the University of Pittsburgh, who also consults for Heartware, said during a session at a Society of Thoracic Surgeons symposium that the device would be approved in the next few weeks.

September 6th, 2012

Resuscitating Resuscitation

Brahmajee Kartik Nallamothu, MD, MPH and Zachary Goldberger, MD, MS

Patients at hospitals where resuscitation attempts lasted longer had higher survival rates according to an observational study involving patients with in-hospital cardiac arrests between 2000 and 2008 published in this week’s Lancet. Two of the study authors, Drs. Zachary Goldberger and Brahmajee Nallamothu answered CardioExchange’s questions.

What questions or comments do you have about this provocative study?

It is widely believed that prolonged attempts at resuscitation are not beneficial. What was the impetus for conducting your study?

As you mention, many practitioners remain reluctant to continue resuscitation efforts for too long when return of spontaneous circulation does not occur early during the course of an arrest. The question there is how long is too long? Unfortunately, there are few empirical data to guide practitioners on this question. It is an extremely difficult decision to make during the course of an arrest because of its obvious implications – i.e., the patient dies when you stop.

How did you frame your analysis?

We initially focused our attention on survivors. Nearly 50% of the patients in our sample survived the arrest, and approximately 87% of those achieved a return of spontaneous circulation by 30 minutes. We were a bit surprised that this wasn’t a higher percentage, and this suggested that some patients only survive after longer resuscitation efforts. We then focused on non-survivors, and found that fewer than 23% of those who died were resuscitated for at least 30 minutes. So our message here was that there are clearly a non-trivial number of patients who need more than 30 minutes to achieve return of spontaneous circulation, and attempts in most patients are rarely extended for this long. We also found that the length of resuscitation attempts in non-survivors varied substantially across hospitals.

Your analysis is unusual because it focuses on a hospitals’ length of attempts in non-survivors to examine survival rates. Can you explain this?

This is an important point. We were able to arrive at our main finding largely because of variation among hospitals’ practice patterns for resuscitation duration in patients who ultimately didn’t survive (i.e., non-survivors), prior to pronouncing a death. In essence, we examined whether the predilection for “how long” a hospital attempts resuscitation is related to how likely a successful outcome would be in their patients. We found that a patient’s likelihood of survival was higher at hospitals that, on average, resuscitated non-survivors for a longer period of time.

Now it is important to note that hospitals in the quartile with the longest resuscitation duration had more than 50% longer attempts than those in the shortest quartile (25 minutes versus 16 minutes). While it is a seemingly small difference in time, these additional minutes have substantial implications in critically-ill patients when physicians are trying to evaluate clinical responses and provide additional treatments.

It seems particularly surprising, and encouraging that neurological outcomes did not differ between the hospital quartiles.

This is good news since a major concern is that prolonged efforts might be leading to higher rates of survival at the expense of worse neurological outcomes. One explanation is that these are in-hospital cardiac arrests, so chest compressions and other supportive measures were likely to be continuous during the entire event.

So, can your work recommend an optimal duration for which to resuscitate hospitalized patients?

That’s a great question, and it is likely that most readers will want to have a simple answer. But we don’t think we are there just yet. We need to be cautious about interpreting these findings. We cannot identify an optimal duration for all patients. How long to continue resuscitation efforts for any individual will depend on a number of patient and arrest-related factors. It will therefore continue to remain a bedside decision that requires clinical judgment. Furthermore, it needs to be stated that we identified an association. This may or may not be causal. For example, hospitals with longer attempts may better in other aspects of resuscitation care, such as their implementation of standardized protocols. We hope this paper will spur future work in in this area.

Ultimately the duration of resuscitative efforts comes down to a bedside decision. Overall, we hope that these data will make practitioners (including ourselves) more aware that some patients may benefit from more time, and – faced with a hospitalized in cardiac arrest – ask whether the patient in front of you might be one of those cases.