February 23rd, 2011

The Passion of Medicine and Its Music

Greg Bratton, MD

I admit it. International medicine and I don’t dance.

I admit it. International medicine and I don’t dance.

Whereas a lot of my former classmates and current colleagues have gone to Brazil, Ghana, Haiti, Israel, Thailand, and Papua New Guinea for medical missions, I typically travel only as far away as high school football buses can go on a tank of gas. I prefer the comfort of stadium lights and training rooms to that of lean-tos and thatch huts. And I much prefer the smell of fresh cut grass on a Friday night to the odor that still lingers in the streets of Port-au-Prince or the smell of disease in Ghana.

I don’t think this means I am less of a doctor or less of a person; it is just that my passion resides elsewhere. I have great admiration for my colleagues who have braved harsh living conditions and social turmoil to provide care to the indigent of other countries. I learn from their stories of treatment under duress, operating with limited supplies and unsanitary conditions. I embrace their creativity, spontaneity, and resourcefulness. But most of all, I respect their unwavering dedication to serving others.

Ironically for me, international health is a huge player in our residency here in Fort Worth. Not only do we have a rather large contingent of Family Medicine residents who participate in mission trips, we have our own International Health Clinic that provides care to refugees living in Tarrant County. On any given day, we might treat patients from Somalia, Burma, India, or any other remote area of the world. In addition, we have several faculty members who have made international medicine a huge part of their career.

Dr. John Gibson and Dr. David McRay, both graduates of our program, have each spent a significant amount of time in foreign lands. Dr. Gibson lived in and practiced medicine in Thailand for 20+ years, doing everything from primary care to surgery. Dr. McRay, meanwhile, leads multiple medical missions every year, most recently to Haiti and Israel.

But probably one of the most impressive men associated with our program and involved in international medicine never actually was a part of our program. To be honest, I never even met him. Although in reading about him, I wish I would have had the opportunity. Luckily, though, I have the privilege to train alongside his daughter, Kate, who is a third-year resident with me here at JPS.

Dr. Thomas Little, an optometrist from upstate New York, was 1 of 10 medical missionaries murdered while returning home after a humanitarian mission in northern Afghanistan in early August 2010. In the late 1970s, Dr. Little and his wife, Libby, went to Afghanistan as relief workers and ended up raising their three daughters in the war-torn nation while treating thousands of needy patients each year. Their mission: offering vision care and surgical services to those in regions where medical assistance of any type was virtually absent.

Dr. Thomas Little, an optometrist from upstate New York, was 1 of 10 medical missionaries murdered while returning home after a humanitarian mission in northern Afghanistan in early August 2010. In the late 1970s, Dr. Little and his wife, Libby, went to Afghanistan as relief workers and ended up raising their three daughters in the war-torn nation while treating thousands of needy patients each year. Their mission: offering vision care and surgical services to those in regions where medical assistance of any type was virtually absent.

Unlike my passion, Dr. Little’s passion was always teeming with risk. But Little was reportedly a natural for the job. He spoke the language, knew the local customs, and had the patience and diplomatic skills to handle sticky situations. In fact, in an interview he gave before he died, he recounted times when family picnics ended after attempted Taliban kidnappings. Yet, he and his family stayed “out of a love for the people and a passion for providing eye care for the needy.”

“We raised our three daughters through what was, at times, just hell,” Libby Little said. “A hundred rockets a day was a good day.” She went on to say that warfare in Afghanistan didn’t deter her or her husband. “If you’re in medicine, I think you feel you can’t leave. If you’re propping up a hospital that’s the only hospital, then you can’t leave when it gets bad.”

Before paying the ultimate price, Dr. Little helped to coordinate the National Organization of Ophthalmic Rehabilitation Eye Care Program in Afghanistan, which is charged with overseeing hospitals and clinics, teaching optometry and administering care in the most rural of areas. Through their work, NOOR is able to bring eye care to millions of Afghans. “He died right where he loved to be — and that was doing eye care in remote areas,” Mrs. Little said from her home in New York. “Our daughters are missing him terribly. But I think their feeling is, too, that this is a real passion that he had.”

Recently, as an “example of generosity and goodwill,” Dr. Little was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom as a way to better know the meaning of sacrifice and the necessity of peace. Along with Dr. Little, other recipients included George H.W. Bush, Dr. Maya Angelou, Warren Buffett, Stan Musial, and Yo-Yo Ma.

Recently, as an “example of generosity and goodwill,” Dr. Little was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom as a way to better know the meaning of sacrifice and the necessity of peace. Along with Dr. Little, other recipients included George H.W. Bush, Dr. Maya Angelou, Warren Buffett, Stan Musial, and Yo-Yo Ma.

“The Medal of Freedom is the Nation’s highest civilian honor, presented to individuals who have made especially meritorious contributions to the security or national interests of the United States, to world peace, or to cultural or other significant public or private endeavors.”

And although he is in great company with those who have also received the award, I believe he was in great company before his death. Dr. Little was in the company of thousands of selfless individuals who also stare death in the face on a daily basis just to bring health and peace and resolution to troubled lands all across the world. In my mind, when his wife received this award from President Obama in honor of her husband, she was receiving the award for all the Dr. Gibsons and Dr. McRays out there who sacrifice their time and money, as well as risk their lives, to fulfill their passion.

So I want to take this opportunity and say thank you to all those who fall into this category. Through your efforts, our world has a better chance of healing its wounds.

I might not be able to dance to your music, but I do love listening to it.

February 14th, 2011

Practice-Changing (or at Least Interesting!) Articles

Greg Bratton, MD

Recent advances and discussions in medicine are the cornerstone of Journal Watch. To provide some insight into what I believe is potentially the most practice-changing current medical information for busy clinicians, I will be highlighting three articles every other week that I think are interesting, relevant, and, in some cases, just plain fascinating. I hope my selections allow you, the followers of this blog, to expand your knowledge without spending too much time (that you probably don’t have), and I hope you enjoy the articles I select.

Please feel free to leave a comment on the articles — Do you like them? Dislike them? Agree, disagree, state your opinion, and participate in the discussion. And if you know of another recent interesting article, post a link to it. I would love to read it.

Greg Bratton, MD

Articles of Interest:

Diet Soda Tied to Vascular Risk, With Caveats — Although this was a weak study that was not controlled for variables other than drinking diet soda, the results hint at things to come. For me, I think it is addressing people who order a Big Mac, large fries, and a Diet Coke at McDonalds. Change your eating habits and start exercising — then diet sodas won’t be an issue.

Diet Soda Tied to Vascular Risk, With Caveats — Although this was a weak study that was not controlled for variables other than drinking diet soda, the results hint at things to come. For me, I think it is addressing people who order a Big Mac, large fries, and a Diet Coke at McDonalds. Change your eating habits and start exercising — then diet sodas won’t be an issue.- A Recipe for Medical Schools to Produce Primary Care Physicians — A thought-provoking editorial that, for the most part, I agree with. We definitely need to start putting the “primary” back into primary care. And with the new movement toward Patient Centered Medical Homes, primary care physicians will be in higher demand.

- FDA Approves a Drug to Lower Risk of Preterm Birth in At-Risk Pregnant Women — For women out there who have suffered multiple spontaneous abortions with no know cause, hydroxyprogesterone caproate provides new hope. Only time will tell if it will be successful.

February 9th, 2011

Snow Days in Texas

Greg Bratton, MD

Believe it or not, it snowed in Texas this week. Mixed between our normal seasonal 60-degree days, were 5 days of ice, snow, and wintery chaos. To most outside of the Lone Star State, snow days aren’t that big a deal. You put on a heavier coat, grab the snow shovel, strap the chains on the tires, and trudge your way through life as if nothing happened.

Believe it or not, it snowed in Texas this week. Mixed between our normal seasonal 60-degree days, were 5 days of ice, snow, and wintery chaos. To most outside of the Lone Star State, snow days aren’t that big a deal. You put on a heavier coat, grab the snow shovel, strap the chains on the tires, and trudge your way through life as if nothing happened.But not here in Texas.

In Texas, when it snows, life stops. No one leaves their house. The roads become barren ice lands. The hardware stores sell out of their limited supply of space heaters — usually enough for the occasional power outage — and grocery stores sell canned goods as if the Apocalypse is coming and the only way to survive is to bunker down for years on end.

Case in point, for the 5 days that the Arctic decided to visit North Texas, all the clinics I had scheduled were cancelled, leaving me at home with my wife and son. Sure, I enjoyed myself – making snowmen, sledding, relaxing by the fire, and snuggling under a warm blanket — but the thought did cross my mind, “While I am here enjoying myself, where are my patients, and what is happening with them?”

Unlike a lot of professions, being a doctor dictates that even when most have time off, we don’t. We don’t have Christmas breaks or government holidays. We work. We work because we have patients, and patients don’t schedule their sicknesses or their traumas around a predetermined calendar. In fact, while in residency, I have had to work or be on call every major holiday for the last 3 years. But what are you going to do? Stop practicing medicine? Nope. So, naturally, as I remained homebound, something felt amiss.

The other day, as I relaxed in my pajamas with a hot cup of coffee and the morning paper open to the sports section, I realized that I was beginning to feel guilty. Guilty because the people that count on me most — my patients — were potentially at home struggling with their COPD, fighting a fever, or cursing the heavens because their arthritis pain was out of control. And, yet, here I was, soaking in a few extra days with my son, finally catching my breath after a hectic month on Medicine, and loving it. Truthfully, I was enjoying life.

But what else was I supposed to do? It was snowing in Texas.

Doc Dohner, as the people of Rushville, IL, call him, has been working as a small town physician for the past 55 years. He works around the clock. In fact, in his 55 years of providing care and service to the people of Rushville, Doc has never had a day off. It is reported that, even after he broke his back and suffered a heart attack, he treated patients from his home. “I have to take care of my patients first,” he said.

Doc Dohner, as the people of Rushville, IL, call him, has been working as a small town physician for the past 55 years. He works around the clock. In fact, in his 55 years of providing care and service to the people of Rushville, Doc has never had a day off. It is reported that, even after he broke his back and suffered a heart attack, he treated patients from his home. “I have to take care of my patients first,” he said.

So how does he do it? How does he maneuver around the environment and the unpredictability of life to continue to place patients first? How does he not feel guilty about always working and being away from his family?

Lynn Stambaugh, Doc’s office manager and a former baby that he delivered, thinks that it is because “every day he makes a difference to at least one person, and if you can do that, you can go on.”

After I came across this story, my guilt shifted to shame. Here is a man that not only has sacrificed holidays, but his entire life to serve his patients. And then there was me, at home, playing with my 15-month-old son, and thinking to myself, “I wish I could stay home every day and not go back to work.” I have always said that family will come first in my life, regardless of where I am or what I am doing. This is a belief that I hold dear and vowed, not only personally, but to my wife on our wedding day. However, this fantastic physician in rural Illinois places patients first every day.

So I questioned, “Am I being selfish? Does this reflect on my capacity as a doctor? Are my priorities twisted?”

Then I realized. My priorities aren’t twisted. Doc Dohner has the same mindset that I do. But whereas my family consists of my wife and son, his family included the 4,300 people of Rushville and the 3500 babies he has delivered. He wasn’t trudging through life taking care of patients; he was taking care of his family. He cared when someone was in the emergency room or was in distress, just like I would care if my wife was in the same situation.

I had it right. I should want to be home. I spend way too many nights away, pouring my heart and soul into treating my patients “as if they were family,” — a few days for myself with my real family is just what the doctor ordered.

Plus, I am pretty sure that as I built Frosty with my son, shared a blanket beside the fire, and held him tight to keep warm, I made a difference to him. And that erases any guilt or shame that I may have temporarily experienced.

Now, does anyone know how to treat Cabin Fever?? I have a bad case of it.

January 31st, 2011

The Real Breathless CPR

Greg Bratton, MD

Residency is hard. The hours are long, the work is grueling, and, simply put, hospital food is not good. Many days, we, as residents, walk the wards in a lifeless haze – coasting on the wings of our white coats, our fuel tanks pointing way past empty.

During these times, we find ourselves sitting in wheelchairs that are stored in dark remote corners, questioning whether or not all of this is worth it. For years, our nose has been to the grindstone, and our minds have been focused. Back in high school, our internal compass always pointed towards the Mecca of Medicine. And no matter how hard our roommates or fraternities or coworkers tried to veer us off our path, we stayed true to the course. In one way or another, most of us have followed the standard pre-med algorithm to medical success:

Step 1: Convince yourself that high school grades matter and study hard.

Step 2: Go to a good college. “Good” being based on the science department and not the social scene or sports.

Step 3: Sacrifice fun (parties, vacations, dates, etc.) so you can maintain a 4.0 GPA.

Step 4: Do research because you hear “med schools like it.”

Step 5: Nail the MCAT by staying true to Step 3.

Step 6: Never lift your head from a book while in medical school, even if you’re in the bathroom.

Step 7: Convince yourself to postpone marriage and family because there is “no time.”

Step 8: Nail Step 1 and Step 2 by placing Step 6 on steroids.

Step 9: Get into a good residency program.

Step 10: Don’t sleep. Convince yourself that it’s a sign of weakness and failure.

Then, when you allow yourself a second to take a break, you see your friend who graduated from college with a 2.0 GPA is running his own business; the guy who cheated off you in biology class has now graduated from law school and is driving a Mercedes; and the girl who was clearly in college for her “Mrs.” degree has opened her own boutique and has a home decorating show on HGTV. Moreover, you see yourself: tired, unshaven and in need of a haircut, pale from not seeing daylight, 20 lbs heavier – thanks to late-night McDonald’s runs – and $200,000 in debt.

And just when you think you can’t take it anymore, you meet the patient in room 533.

Mr. 533 is a 59-year-old man who presented to the hospital with a past medical history of diabetes mellitus type II and with the chief complaints of chronic diarrhea and 55-lb weight loss during the last 6 months. Mr. 533 is a self described “pain in the ass” who refuses to go to the doctor “unless I am dead.” This time, though, he presented at the insistence of his wife and is not happy about it.

On admission, Mr. 533 was a well-appearing man who looked older than his stated age. His skin was wrinkled from years of sun exposure, and his hands were calloused from the wear and tear of manual labor. Other than that, his physical exam was completely benign. His labs were negative, but a CT of the abdomen and pelvis showed “enlarged lymph nodes involving the retroperitoneum, pelvis, and the inguinal regions bilaterally; possibly due to a metastatic disease or lymphoproliferative disease such as lymphoma or leukemia; thickening of the rectum possibly neoplasm.”

He initially refused a rectal exam, so it was not until he went for colonoscopy that his rectum could be examined. To make a long story short, Mr. 533 was diagnosed with stage IV metastatic prostate cancer to the colon.

Staying true to form, Mr. 533 was resistant to treatment during his 3-week hospitalization. He refused insulin for his hyperglycemia, refused IVs, and never complied fully with physical exams. However, somehow we did get him to agree to begin treatment for his cancer with Lupron. “But once I receive the injection, I am leaving,” he said.

Mr. 533 received the injection, stayed the night and the next morning, and started to get ready to leave. But, while leaning over to tie his shoes, he fell to the floor in ventricular fibrillation. ACLS protocols were run, and Mr. 533 was shocked twice. Subsequently, he underwent bare-metal stenting of his left anterior descending artery for a subtotal occlusion and had an intra-aortic balloon pump placed for cardiogenic shock. He then spent the next 5 days in a coma in the ICU. Miraculously, the day after we talked to his family about withdrawing care, he woke up. And during the next week or so, he went from delirious to angry to appreciative.

On his day of discharge, I was post-call and tired. I had maybe caught an hour or two of very uncomfortable sleep on a couch and was mentally exhausted from the night’s events. I was without coffee and once again questioning, “Why do I do this?” Nonetheless, I shuffled my emotionally drained and vacant carcass into his room to make sure any questions had been answered and to wish him well.

“Do you have any questions, Mr. 533?”

“No, doc. But I wanted to let you know that you have impressed me and have given me hope like no one else ever has in my life. And I don’t say things like that to many people. So thank you.”

Like a wilted flower that receives water, I instantly felt my emotional tank fill up and my battery get re-energized. And I was immediately reminded why I do what I do. In that moment, just as I had brought life back to him during his arrest, Mr. 533 brought life back to me during mine. This is a true example of breathless CPR.

January 20th, 2011

Autism: What’s the Truth??

Greg Bratton, MD

Hollywood is known for a lot of things: celebrities, the “sign,” the Walk of Fame, and Rodeo Drive. However, Hollywood recently has started to make its name in another way. Between the 1988 film Rain Man and the recent ramblings of ex-Playmate Jenny McCarthy, this iconic location has become a hotbed of controversy about autistic disorders.

Hollywood is known for a lot of things: celebrities, the “sign,” the Walk of Fame, and Rodeo Drive. However, Hollywood recently has started to make its name in another way. Between the 1988 film Rain Man and the recent ramblings of ex-Playmate Jenny McCarthy, this iconic location has become a hotbed of controversy about autistic disorders.

Autism, or more appropriately

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), is “a range of complex neurodevelopment disorders, characterized by social impairments, communication difficulties, and restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped patterns of behavior.” Originally a condition that was diagnosed later in life, the numbers of newly diagnosed pediatric cases are rapidly increasing, most likely because of increased attention brought to it by the media. But the question that should be asked is whether the prevalence of autism is becoming more prevalent or are we just becoming more sensitive to it?

Jenny McCarthy is, without question, partly responsible for this new awareness. She has successfully redefined herself from Playboy pin-up to the face of autism in the media. Jenny has made it her mission in life to provide awareness of and support to autistic children. The motivation behind her undertaking is her son, Evan, who at the age of 2.5 years, was diagnosed with autism.

While on the Oprah Winfrey Show in 2007, she talked about the discovery of her son’s disorder and the trials of dealing with an autistic child. She detailed the horror that so many parents feel when facing their children’s first immunizations. Jenny recounts that even before her son received his vaccines, she tried to talk to her pediatrician about the risk.

“Right before his MMR shot, I said to the doctor, ‘I have a very bad feeling about this shot. This is the autism shot, isn’t it?’ And he said, ‘No, that is ridiculous. It is a mother’s desperate attempt to blame something,’ and he swore at me, and then the nurse gave [Evan] the shot,” she says. “And I remember thinking, ‘Oh, God, I hope he’s right.’ And soon thereafter — boom — the soul’s gone from his eyes…What number will it take for people just to start listening to what the mothers of children who have autism have been saying for years, which is, ‘We vaccinated our baby and something happened.'”

Subsequently, one of her platforms in discussing ASD is raising the alertness of vaccines and their perceived predilection to cause autism. This relationship originated from British physician Dr. Andrew Wakefield’s 1998 Lancet study that stated that the MMR vaccine directlycaused autistic disorders. According to the paper, Wakefield wrote, “We identified associated gastrointestinal disease and developmental regression in a group of previously normal children, which was generally associated in time with possible environmental triggers” — the possible triggers reported were the MMR vaccine in eight cases, and measles infection in one.

Further bringing attention to the association of vaccines and autistic disorders was the use of thimerosal as a preservative. Thimerosal is a mercury compound that is broken down to ethylmercury, which can be neurotoxic in high doses. This preservative has been used since the 1930s, but came under scrutiny when it was noted that as the incidence of autism was rising along with the use of thimerosal in vaccines. In July 1999, the FDA finally concluded that thimerosal be removed from all childhood vaccines because some children were receiving higher amounts of mercury than the established guidelines deemed to be safe. Currently, all childhood vaccines are thimerosal free, seemingly putting this aspect of the controversy to rest .

The other part of the controversy, the link between the MMR vaccine and ASD, should finally be settled as well. In the January 2011 issue of the British Medical Journal, an editorial was published by the BMJ editor, Fiona Godlee, that referred to Dr. Wakefield’s 1998 paper as an “elaborate fraud.” This comes after a reporter exposed that Wakefield and his colleagues altered the facts about their patients in the original study. Brian Deer, a British journalist, compared the patients’ diagnoses in the original paper to those in their hospital charts and found significant discrepancies. Whereas Wakefield stated that he found “gastrointestinal disease and developmental regression in a group of previously normal children,” this new analysis found that 5 of the 12 children had previously documented developmental problems.

Initially questioned because of its small sample size, the original conclusions never gained widespread medical acceptance because multiple repeat studies throughout the years continued to refute the findings. Now, convincingly, it can widely be accepted that vaccines are not directly related to ASD.

However, the coals have been burning too long on this fiery debate to simply cool off. On Jenny McCarthy’s website, it continues to say “We hope the media will take the time to read the actual Lancet study, rather than repeating the message of a vaccine-industry funded media circus… If all the science on vaccines and autism has been done, how come no one has yet looked at unvaccinated children?” The National Autism Association maintains on their website, “To date, studies conducted or funded by the CDC that purportedly dispute any correlation between autism and vaccine injury have been of poor design, under-powered, and fatally flawed. The CDC’s rush to support and promote such research is reflective of a philosophical conflict in looking fairly at emerging theories and clinical data related to adverse reactions from vaccinations.”

Just as one controversy quiets, another arises. To further confound the issue as to what causes autism, an article by Cheslack-Postava et al., published in the January 2011 issue of Pediatrics, the official journal for the American Academy of Pediatrics, reports the incidence of autism is threefold greater when siblings are born within 1 year of each other. It further states that siblings born 12 to 23 months after their first-born siblings have twice the risk, while siblings born 24 to 35 months after their first-born siblings are 26% more likely to develop autism than are their first-born siblings. This study was conducted retrospectively on 660,000 children born in California between 1992 and 2002.

So what are we to think? Do birth order and timing affect the likelihood of autism?

As far as science goes, due to the complexity of the disease process and its variable range of severity, no conclusive evidence tells us what causes autism. The working theory is that it is a condition that is influenced collectively by both genetics and environment. Researchers have located and identified several genes that might be associated with this condition but, again, data are inconclusive. Other studies suggest that it is caused by anatomic irregularities in the brain or to abnormal levels of neurotransmitters (e.g., serotonin).

Regardless, we can safely to say that the jury is still out. From a primary care perspective, we should be mindful of the perceptions that our patients have when it comes to autism and vaccines. Sometimes reassurance is all it takes, but often times, we are left with their decision not to vaccinate, even if it is against our own recommendations. And with this new study about the timing of pregnancies, who knows what the future holds.

One thing is for sure; whoever finds the answer about what causes autism undoubtedly will have their name in lights and a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame — probably right next to Jenny McCarthy’s.

One thing is for sure; whoever finds the answer about what causes autism undoubtedly will have their name in lights and a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame — probably right next to Jenny McCarthy’s.

January 13th, 2011

Help Me Help You

Greg Bratton, MD

Although this clip is from a movie about a sports agent trying to negotiate a new contract for an entitled egotistical football player, every time I see it, it reminds me of work. Put a white coat on Tom Cruise, and transplant them from a shower room to an exam room, and it becomes a pretty accurate portrait of my daily conversations with patients.

In fact, when I was on Medicine call the other night, I had this exact conversation with two patients. The first was a 33-year-old male who overdosed on Rohypnol, went into cardiac arrest, and was resuscitated, intubated, and taken to the ICU for monitoring; the other was a 65-year-old end-stage renal disease patient on chronic dialysis with a fever and a 10 cm x 10 cm abscess overlying his AV shunt.

Briefly, my conversations went something like this…

The overdose patient awoke in the ICU, was extubated, and said, “I am leaving. Give me the papers.” When I explained to him that we would like to monitor him for a little longer (especially since his heart had stopped less than 12 hrs ago!!!) and get him the social help that he needed, he refused, and began pulling out all his IVs to leave.

“Help me help you,” I said. “You died last night. Next time it might be for good.”

He replied, “I don’t want your help.” Then he signed his Against Medical Advice (AMA) papers and walked out of the room and down the hallway in nothing but his boxers and no-slide hospital socks — to go and get his next high, I’m sure.

The older gentleman with the abscess was even more disappointing. After claiming to be very “in tune” with his health and aware of his infection, he refused admission to the hospital because, “I don’t like the dialysis machines, and the food is bad.” When I told him that it was my medical opinion that he be admitted and treated with IV antibiotics and a probable surgical I&D, he said, “I know medicine. I read the internet, and this is no big deal. Just give me some pain meds, and I’ll be fine.”

“Sir, you have an abscess at a very dangerous location. It can ruin your graft, but more importantly, you’re febrile and may be on your way to bacterial sepsis,” I emphasized.

After gaining no ground with my reasoning, I gave him the AMA paperwork. “I’m not signing that unless you treat my pain,” he said. “I need hydrocodone 7.5/500. That is the ONLY thing that works.”

To which I replied, “This is not a trade-off. Help me help you. You could get very sick from your infection. Let me treat you.”

Needless to say, he left without treatment or pain meds.

Patient autonomy is one of the cornerstones of medical ethics. It is defined as giving patients the right to make decisions about their own care without the influence of a physician. The twist is that it is the physician’s responsibility to provide all the information to that patient about their condition so that they can make an informed choice, but not to decide for them.

However, as I experienced the other night, sometimes you want to throw ethics out the window, lock the patient down, and do what you know is “right” for them. Other times you want to beg and plead, “Help me help you” as Jerry Maguire did in the clip. But, alas, we do not. We hold true to the ethics of medicine and allow patients to make, in some instances, very poor decisions.

The Hippocratic Oath states, “I will prescribe regimens for the good of my patients according to my ability and my judgment and never do harm to anyone … But I will preserve the purity of my life and my arts.”

There are two parts of this oath that strike me in these particular situations. The first is primum non nocere. I have to remind myself that what might be beneficial to me, might be harmful to others. Meaning, no matter how much schooling or studying or experience I have in medicine, it holds no weight to what my patients are experiencing in life. To some, my helping prolong their life or heal their wounds might be, in one way or another, harmful to them. Often, the choices that patients make that seem absurd to me, are calculated and well thought out to them.

The other is “preserving the purity of my arts.” No matter how I feel personally or professionally about a patient or their condition, as soon as I impart my frustrations and biases on that patient, my “art” becomes tarnished. I respect medicine and the forefathers of the profession too much to bring shame on it. So I stick to the facts and hope that my patients make the right medical choice for them.

As long as we practice medicine, we will be faced with difficult patients — those who feel entitled, those who don’t take their medications, those that skip appointments, and those that refuse treatment. However, our responsibility is to continue to do our jobs well by providing our patients with all the resources and information that they need to make informed choices, good or bad, even if they express no appreciation or interest. And when they make poor choices, our job is to be there for them, without bias, when they return.

We took an oath on it.

“If I keep this oath faithfully, may I enjoy my life and practice my art, respected by all men and in all times; but if I swerve from it or violate it, may the reverse be my lot.”

December 20th, 2010

Residents’ Christmas Carol Sing-Along

Greg Bratton, MD

On the first day of Christmas,

the ER sent to me…

A cardiac arrest without a DNR.

On the second day of Christmas,

the ER sent to me…

Two gunshot wounds,

And a cardiac arrest without a DNR.

On the third day of Christmas,

the ER sent to me…

Three drug overdoses,

Two gunshot wounds,

And a cardiac arrest without a DNR.

On the fourth day of Christmas,

the ER sent to me…

Four chest pain rule-outs,

Three drug overdoses,

Two gunshot wounds,

And a cardiac arrest without a DNR.

On the fifth day of Christmas,

the ER sent to me…

Five hypertensive crises,

Four chest pain rule-outs,

Three drug overdoses,

Two gunshot wounds,

And a cardiac arrest without a DNR.

On the sixth day of Christmas,

the ER sent to me…

Six hearts a-failing,

Five hypertensive crises,

Four chest pain rule-outs,

Three drug overdoses,

Two gunshot wounds,

And a cardiac arrest without a DNR.

On the seventh day of Christmas,

the ER sent to me…

Seven drunks a-singing,

Six hearts a-failing,

Five hypertensive crises,

Four chest pain rule-outs,

Three drug overdoses,

Two gunshot wounds,

And a cardiac arrest without a DNR.

On the eighth day of Christmas,

the ER sent to me…

Eight patients seizing,

Seven drunks a-singing,

Six hearts a-failing,

Five hypertensive crises,

Four chest pain rule-outs,

Three drug overdoses,

Two gunshot wounds,

And a cardiac arrest without a DNR.

On the ninth day of Christmas,

the ER sent to me…

Nine ladies bleeding,

Eight patients seizing,

Seven drunks a-singing,

Six hearts a-failing,

Five hypertensive crises,

Four chest pain rule-outs,

Three drug overdoses,

Two gunshot wounds,

And a cardiac arrest without a DNR.

On the tenth day of Christmas,

the ER sent to me…

Ten bellies a-hurting,

Nine ladies bleeding,

Eight patients seizing,

Seven drunks a-singing,

Six hearts a-failing,

Five hypertensive crises,

Four chest pain rule-outs,

Three drug overdoses,

Two gunshot wounds,

And a cardiac arrest without a DNR.

On the eleventh day of Christmas,

the ER sent to me…

Eleven smokers gasping,

Ten bellies a-hurting,

Nine ladies bleeding,

Eight patients seizing,

Seven drunks a-singing,

Six hearts a-failing,

Five hypertensive crises,

Four chest pain rule-outs,

Three drug overdoses,

Two gunshot wounds,

And a cardiac arrest without a DNR.

On the twelfth day of Christmas,

the ER sent to me…

Twelve uncontrolled sugars,

Eleven smokers gasping,

Ten bellies a-hurting,

Nine ladies bleeding,

Eight patients seizing,

Seven drunks a-singing,

Six hearts a-failing,

Five hypertensive crises,

Four chest pain rule-outs,

Three drug overdoses,

Two gunshot wounds,

And a cardiac arrest without a DNR.

Dashing through the halls

After a brief one-hour snooze

O’er the floors we go

Yawning all the way

Codes on walkie-talkies called

Making interns cry

What fun it is to bag and squeeze

A coding man tonight!

Oh, pager page, pager page

Paging all the time

Oh, how hard it is to sleep and dream

With that bleeping beeping chime

Pager page, pager page

Paging all the time

Oh, how hard it is to sleep and dream

With that bleeping beeping chime

An hour or so ago

I thought I’d take a nap

And soon Nurse Keep-Me-Up

Was again beeping on my side

The man was sick and still

Breathing was no longer his deal

So we jumped into the coding room

And began our valiant moves!

Oh, pager page, pager page

Paging all the time

Oh, how hard it is to sleep and dream

With that bleeping beeping chime

Pager page, pager page

Paging all the time

Oh, how hard it is to sleep and dream

With that bleeping beeping chime

Oh, pager page, pager page

Paging all the time

Oh, how hard it is to sleep and dream

With that bleeping beeping chime

Pager page, pager page

Paging all the time

Oh, how hard it is to sleep and dream

With that bleeping beeping chime

I’m Dreaming of a Codeless Call

I’m Dreaming of a Codeless Call

I’m dreaming of a codeless call

Unlike the ones I have always had

Where the patients listen

And medicines are taken

And I’m able to avoid anything bad.

I’m dreaming of a codeless call

With every pager sound I hear

I pray my night be slow and quiet

And may all my patients stay outta my sight.

I’m dreaming of a codeless call

With every pager sound I hear

I pray my night be slow and quiet

And may all my patients stay outta my sight.

Immunizations Are Coming Your Way

Immunizations Are Coming Your Way

You better watch out

You better not cry

Better not pout

I’m telling you why

Immunizations are coming your way

He’s making a fist,

And shaking his head;

Gonna be like a wrestling a gorilla in bed.

Immunizations are coming your way

He sees you when you’re sneaky

He knows when the needle is near

He knows if you’ve been slow or fast

So be fast for goodness sake!

O! You better watch out!

You better not cry.

Better not pout, I’m telling you why.

Immunizations are coming your way.

You better watch out

You better not cry

Better not pout

I’m telling you why

Immunizations are coming your way

He’s making a fist,

And shaking his head;

Gonna be like a wrestling a gorilla in bed.

Immunizations are coming your way

He sees you when you’re sneaky

He knows when the needle is near

He knows if you’ve been slow or fast

So be fast for goodness sake!

O! You better watch out!

You better not cry.

Better not pout, I’m telling you why.

Immunizations are coming your way.

Immunizations are coming your way.

Here comes the Intern!

Here comes the Intern!

Right down the hospital’s hall!

Nurses and techs and all their patients

Have been waiting on his call.

Phones are ringing, alarms are beeping;

All is chaotic and right.

Cross your fingers and say your prayers,

‘Cause the intern comes tonight.

Here comes the Intern!

Here comes the Intern!

Right down the hospital’s hall!

He’s got a coat that is filled with books

That tell him how to heal.

See the sweat stains on his scrubs,

Oh, what a frightening sight.

Jump in bed, cover up your head,

‘Cause the Intern comes tonight.

Happy Holidays!

December 13th, 2010

Healthy Is Not Always Convenient

Greg Bratton, MD

7-11s and McDonalds are everywhere. They are successful because they are convenient, and we embrace convenience. We don’t want to go out of our way for anything. We have evolved into a society of drive-throughs, Internet shoppers, and Garmin users. If a short cut exists, we take it.

7-11s and McDonalds are everywhere. They are successful because they are convenient, and we embrace convenience. We don’t want to go out of our way for anything. We have evolved into a society of drive-throughs, Internet shoppers, and Garmin users. If a short cut exists, we take it.

Probably two or three times every day, patients ask me what I can prescribe that will help them lose weight. My answer is always “exercise and a conscientious diet,” but that goes over like a lead balloon. Nobody wants to commit themselves to moderate-intensity exercise for 2.5 hours every week and 2 or more days per week of muscle-strengthening exercises. This would mean that they would have to take time out of their routine and change their otherwise sedentary ways. They are looking for the quick fix — HCG injections, gastric bypass, or, my personal favorite, liposuction. But as soon as I mention the 500-calorie-a-day diet that goes with the HCG injections, or the process of qualifying for gastric bypass — including a proven inability to lose weight through diet and exercise — or the diet that they must maintain after surgery, they change their minds . None of these options is as convenient as their current lifestyle of health negligence.

The idea of convenience is again evident when I discuss screening colonoscopies with my patients. Usually, the conversation goes something like this…

“You’re 50 years old now, so we need to talk about a screening colonoscopy.”

“Ok, Doc. I’ll do whatever you say.”

After addressing all the risks and benefits of the procedure and detailing how the procedure is performed, I say, “You will need to do a bowel prep the night before.”

“A what …???”

“A bowel prep. It’s a gallon of laxative you drink to clean out your colon. You’ll be on the toilet all night, but it’s necessary for a complete exam.”

To which the patient replies, “Nope. Not going to do it. Can’t I just swallow the camera pill?”

I have more patients than I can count who refuse to have colonoscopies because of the inconvenience of the prep the night before. Some just don’t like the idea of losing sleep, but others have bigger barriers to overcome. One of my homeless patients said it best, “I don’t have anywhere that I can ‘go’ that many times.”

But medicine is finally starting to give patients ways to “conveniently” adhere to our recommendations. In the December 3rd issue of Journal Watch Gastroenterology, I read a summary of an article from the American Journal of Gastroenterology that showed a 4-L bowel prep, taken on the morning of an afternoon colonoscopy, improved efficacy and tolerability versus the traditional day-before preparation. This article demonstrated that dosing in this manner caused less disruption of the workday prior to the day of colonoscopy and decreased the amount of sleep deprivation the night before — and prep scores were better than those after nighttime cleansings. For people like my homeless patient, having the option of arriving at the center the morning of the procedure, doing a bowel prep, and having a scope done all at once will undoubtedly improve adherence.

Other areas of medicine are also moving toward convenience. In the world of cardiology, dabigatran has gained FDA approval for the “prevention of stroke and blood clots in patients with abnormal heart rhythm (atrial fibrillation).” As one of the Journal Watch General Medicine authors noted, the attractiveness of this drug lies in that it is given in a fixed twice daily dosing and does not require international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring. If, and when, this drug reaches the mainstream in the U.S., Coumadin clinics and at-home finger sticks could become a thing of the past. Coincidentally, the other day, I had a patient say to me, “When can I stop taking Coumadin? I hate pricking my finger.” Unfortunately for him, he had a 4-vessel coronary artery bypass complicated by a pulmonary embolism, so my response was, “Never, unless we get dabigatran on formulary.”

Other areas of medicine are also moving toward convenience. In the world of cardiology, dabigatran has gained FDA approval for the “prevention of stroke and blood clots in patients with abnormal heart rhythm (atrial fibrillation).” As one of the Journal Watch General Medicine authors noted, the attractiveness of this drug lies in that it is given in a fixed twice daily dosing and does not require international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring. If, and when, this drug reaches the mainstream in the U.S., Coumadin clinics and at-home finger sticks could become a thing of the past. Coincidentally, the other day, I had a patient say to me, “When can I stop taking Coumadin? I hate pricking my finger.” Unfortunately for him, he had a 4-vessel coronary artery bypass complicated by a pulmonary embolism, so my response was, “Never, unless we get dabigatran on formulary.”

Unlike the fast-food industry’s negative effect on our nation’s health, convenience in medicine is not bad. It should lead to improved adherence and better patient outcomes. In just these examples, we could find more early-stage colon cancers that otherwise would have gone undetected and improve the quality of life for those on chronic anticoagulation.

Now, if we could just find a pill that is equivalent to exercise, our medical practices might become as successful as 7-11s and McDonalds.

December 6th, 2010

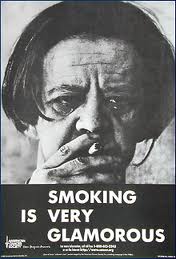

Smoke and Mirrors

Greg Bratton, MD

I saw two patients last week that really made me scratch my head.

The first was a 15-year-old girl who was smoking a pack of cigarettes daily and had been for 3 years; the other was a 26-year-old man who smoked 1.5 packs daily for 10 years and had recurrent oral ulcers and bleeding gums. In sitting and talking with these two patients, it became blatantly obvious that the risks of tobacco use – such as developing emphysema or lung cancer – didn’t scare them. Both said, matter-of-factly and without hesitation, “I’ll worry about that when I have symptoms.”

As you might imagine, I was at a loss for words. For years, schools, billboards, doctors, and the government have been trying to educate Americans about the ills that tobacco use can bring. Smoking has gone from being the cool thing to do to being socially unacceptable. Restaurants have banned indoor smoking sections, and ballparks, office buildings, and public venues have designated smoking areas that are far removed from the main flow. Society has recognized that smoking is bad, but, as evidenced by my patients, our youth are still struggling with the concept.

As you might imagine, I was at a loss for words. For years, schools, billboards, doctors, and the government have been trying to educate Americans about the ills that tobacco use can bring. Smoking has gone from being the cool thing to do to being socially unacceptable. Restaurants have banned indoor smoking sections, and ballparks, office buildings, and public venues have designated smoking areas that are far removed from the main flow. Society has recognized that smoking is bad, but, as evidenced by my patients, our youth are still struggling with the concept.

Recently, the FDA proposed implementing a new policy, beginning June 22, 2010, called the Tobacco Control Act, that would require the packaging of cigarettes to have “larger and more visible graphic health warnings” to depict the negative side effects of tobacco use. As you can imagine, this proposed change engendered a public outcry about the appropriateness of such images. Apparently, the thought of seeing what will happen instead of just hearing about what will happen with chronic tobacco use is repulsive and distasteful. I say we need to make this happen.

To me, it can all be compared to owning a car. To most people, a car is a status symbol, a marker for how financially sound you are. People care how their cars look: maybe they add a few accessories, buy new rims, get a custom paint job, or even add gold trim. However, my bet is that 3000-mile oil changes, new spark plugs, tire rotations, and other standard maintenance items go undone because no one asks to look under the hood. The same is true of the body: As long as kids can look in the mirror and see “normal,” they don’t care about what is going on inside. As a primary care provider, it is my job to redirect their focus to their engines.

To me, it can all be compared to owning a car. To most people, a car is a status symbol, a marker for how financially sound you are. People care how their cars look: maybe they add a few accessories, buy new rims, get a custom paint job, or even add gold trim. However, my bet is that 3000-mile oil changes, new spark plugs, tire rotations, and other standard maintenance items go undone because no one asks to look under the hood. The same is true of the body: As long as kids can look in the mirror and see “normal,” they don’t care about what is going on inside. As a primary care provider, it is my job to redirect their focus to their engines.

We are in the business of prevention. This means routinely pushing for and obtaining routine colonoscopies, Pap smears, mammograms, prostate exams, and blood work. It is our job to do the “scheduled maintenance” for our patients and to advocate for a healthy lifestyle, even before any symptoms appear. In other words, we need to make it clear to our patients that, although their bodies look good, their engines could be failing fast. Sometimes, in order to get this message across, threatening a little future cosmetic damage can do the trick.

Thus, when discussing smoking habits with my patients, I informed the teenage girl that her heavy smoking not only leads to lung cancer, bladder cancer, and other well known side effects, but also to bad breath, odor in her clothes, wrinkling of the skin on her face, staining of her teeth, infertility, and menstrual problems including irregular bleeding.

Thus, when discussing smoking habits with my patients, I informed the teenage girl that her heavy smoking not only leads to lung cancer, bladder cancer, and other well known side effects, but also to bad breath, odor in her clothes, wrinkling of the skin on her face, staining of her teeth, infertility, and menstrual problems including irregular bleeding.

With the “too-cool-for-school” 26-year-old, I mentioned that he should have his oral lesions biopsied to rule out cancer, because if the lesions were malignant he could lose his tongue and lower jaw. Plus, I told him that he could be facing a future of impotence if he continues smoking at his current pace.

With the “too-cool-for-school” 26-year-old, I mentioned that he should have his oral lesions biopsied to rule out cancer, because if the lesions were malignant he could lose his tongue and lower jaw. Plus, I told him that he could be facing a future of impotence if he continues smoking at his current pace.

Sadly (but also thankfully), I think my message got through.

November 22nd, 2010

Thanks (for) Giving

Greg Bratton, MD

This is my favorite time of year. Not because the leaves are falling and Texas is finally cooling off, but because the upcoming holidays give me time to reflect on the year’s events and appreciate what I have been given. For some, this might bring to mind a big promotion, a new addition to the family, or an “opportunity of a lifetime.” For me, it provides a moment to think about my patients —their lives, their struggles, and their strength — and the lessons that I have learned as a result.

This is my favorite time of year. Not because the leaves are falling and Texas is finally cooling off, but because the upcoming holidays give me time to reflect on the year’s events and appreciate what I have been given. For some, this might bring to mind a big promotion, a new addition to the family, or an “opportunity of a lifetime.” For me, it provides a moment to think about my patients —their lives, their struggles, and their strength — and the lessons that I have learned as a result.

So with the spirit of Thanksgiving hanging heavy in the air this week, I want to take this opportunity to say “thank you” to all those that have blessed me with their gifts.

First, I want to thank my cadaver from the first year of medical school. Similar to other schools around the country, my medical school utilized a Willed Donor Program that allows living individuals to perform the ultimate charitable act and donate their remains to the university in order to “assist, in a material way, the transmission of medical knowledge across generations.” Although I will never know your name or be able to thank you directly, I want you to know that your gift will never be forgotten. Thanks for giving.

“Feeling gratitude and not expressing it is like wrapping a present and not giving it.”

–William Arthur Ward

I want to say thank you to all my clinic patients that push me to be a better doctor, that challenge me to read and be up-to-date on the latest literature and guidelines, and who, without fail, never make a “hypertensive visit” just about hypertension. I want to thank you for allowing me to be a part of your intimate lives, to share in your successes and struggles, and for giving me permission to walk beside you during your life’s difficult journeys. Thanks for giving.

I want to say thank you to all the mothers that I shared the gift of life with. I want to thank you for reminding me that practicing medicine is not a job, but a privilege that not many get to experience. Thanks for giving.

I want to say thank you to all the mothers that I shared the gift of life with. I want to thank you for reminding me that practicing medicine is not a job, but a privilege that not many get to experience. Thanks for giving.

I want to thank my ICU patients who have shown me what a “fighting spirit” is, who have pushed me to the brink of collapse, and who have — at times — made me feel that I had witnessed a miracle. Thanks for giving.

I want to thank those that have perished in my care. I want to thank you for allowing me to be a part of your last moments, for providing me the chance to learn what death is all about, and for affording me the opportunity to share in the grief with your family. Thanks for giving.

I want to thank those that have donated an organ, money, time as a volunteer, or any other contribution to a patient, a hospital, an organization, or some other recipient. Thanks for giving.

I want to thank those that have donated an organ, money, time as a volunteer, or any other contribution to a patient, a hospital, an organization, or some other recipient. Thanks for giving.

I want to thank my fellow residents, my attendings, and all the nurses that make the stress, the uncertainty, and the challenge of my job enjoyable. I want to thank you for your insights, your critiques (good and bad), and your undying enthusiasm. Thanks for giving.

But most of all, I want to thank those that entrust their health to resident physicians at teaching hospitals. You are the backbone to our profession and, without you, we would be nothing. Thanks for giving.

Lastly, to everyone else whom I have yet to encounter, thank you in advance. For with every new patient I meet, I become a better, more complete doctor. Thanks for giving.

Obviously, this is only a sampling of all those that truly deserve “thanks.” From Day 1 of medical school until the day we retire, it is those around us that make our passion for medicine a reality. And more often than not, these are the ones that get taken for granted, overlooked, or even forgotten. So, this year, when given the opportunity to reflect and give thanks, think of those that have helped mold you into who you are. Think of your assistants, your mentors, your patients and the families for whom you care. They are the ones who have given us the greatest gifts.

And remember to say, “Thanks for giving.”