September 5th, 2016

Men, Women, or Both?

April Edwards, MD

April Edwards, MD, is the 2016-17 Chief Resident for Internal Medicine/Pediatrics program at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine.

Last month, as I was adjusting to my new role as a newly minted attending (affectionately referred to by many as a “pre-tending”), I had the opportunity to precept some of our strong upper levels in our ambulatory clinic. Luckily for me, they were doing a great job, which helped the whole thing feel less scary to me. During this clinic, one of the residents came into the workroom to exclaim excitedly —”I just asked someone if they have sex with men, women, or both — and they said both!” This reaction was not because this resident is bigoted nor that he wasn’t incredibly professional with great bedside manner. It was exactly the opposite — he diligently screened all of his patients for all of the “checky-boxes” we learned about in medical school, and he was just excited about the opportunity to care for a relatively underrepresented patient. But it made me pause for a moment and reflect on something that has become a hot topic for me locally.

I am from North Carolina. And earlier this year, my state passed a House Bill (HB2) that bans transgendered people from using the public restroom that aligns with their gender identity. The original Bill also nullified local ordinances that protected discrimination based on sexual orientation. The outcry from much of the public sector has been very loud and very visible, with people adopting anti-HB2 slogans like #WeAreNotThis and #Ya’llMeansAll. Thus, sexual identity has become a topic of conversation here in North Carolina, and also nationally, as companies, artists, investors, and developers pull out of North Carolina, so as not to support HB2. Most recently, the NBA AllStar game announced that it would not be holding its event in Charlotte.

This means that we, as physicians, have been talking about this issue as well, many of us more so recently. Institutions in our state are now having Grand Rounds on Transgendered Identity and Development, and the new Center for Child and Adolescent Gender Care just opened locally. In an attempt by many to not “miss” the LGBTQI community in a time when many feel neglected or discriminated against, some of us well-meaning physicians are at risk for getting a bit sidetracked by gender identity. By that, I mean I think it is easy to excitedly focus on a patient’s sexual identity in an attempt to show that you are supportive, in a time when this group is being marginalized. To congratulate yourself for being hip and open. But in doing so, it sets us up to miss an opportunity to support this community with some of the well studied means that we already have.

Recently, in NEJM Journal Watch, a physician-author reviewed an article addressing the health and health risk factors of the LGBQ community. Of the more than 65,000 people surveyed, those who identified as gay/bi/lesbian had higher rates of psychological stress and higher self-reported rates of substance use and abuse.

Because sexual orientation has been stigmatized for so long, I think it is incredibly easy for physicians, regardless of their personal or political views, to become fixated on this aspect of the patient. This often happens with only good intentions — physicians trying to be open and supportive and talk openly about issues of sexual orientation. Unfortunately, this hyper-focus often can happen to the detriment of other important health issues. I have been guilty of this, as I am willing to posit, have many of my peers.

What this aforementioned study suggests to us is that one of the best things we can do is spend a little extra time with this (LGBTQI) subset of our patients to actually discuss substance use and support systems in more depth than just checking off boxes on an intake questionnaire form. We know how to do this, and when we take the time, we can do it well. We have long had data articulating the many benefits of tobacco cessation, and the myriad other adverse health events tied to it. We should ask (and actually listen!) about other substance use, and counsel appropriately. And we ought to recognize the unique stressors weighing on these patients and spend more time exploring support systems and making sure they are adequately addressed and recognized.

Asking if someone’s sexual partners are male, female, or both can be a useful question and tool. But rather than us having it be the “checky-box” that defines them, let us instead let it be the start of well-tailored care centered in listening well.

August 29th, 2016

Multiple Choice Medicine

Amanda Breviu, MD

You are currently on inpatient wards and notice your chief medical resident has been demonstrating erratic behavior, frequently muttering about MEN syndromes and antibodies associated with rheumatologic diseases and has been reciting gene translocations. What is the most likely cause of her symptoms?

A. Hospital-associated delirium

B. Conversion disorder.

C. Symptoms related to completing an excess number of multiple choice questions in preparation for taking Internal Medicine boards.

If you guessed C, you understand what I have been going through in the past several weeks. Although I hope no one actually thought my behavior was erratic, I spent the majority of my free time prior to August 19th preparing for the American Board of Internal Medicine Certification Exam. And I’m in good company. Recent graduates of internal medicine residencies across the country have also been preparing for and taking this exam in late August, often concurrently with starting their first “real” jobs or completing training with fellowships. It is a test that you prepare for throughout residency with didactics lectures and annual practice exams (in-training exams). Attendings are constantly preaching important clinical information on rounds, typically using the phrase, “this will definitely be on your boards.” As a chief medical resident, I have found myself spouting board-style questions to start off our morning reports and often using that same phrase to enforce the importance of this information to interns and residents.

If you guessed C, you understand what I have been going through in the past several weeks. Although I hope no one actually thought my behavior was erratic, I spent the majority of my free time prior to August 19th preparing for the American Board of Internal Medicine Certification Exam. And I’m in good company. Recent graduates of internal medicine residencies across the country have also been preparing for and taking this exam in late August, often concurrently with starting their first “real” jobs or completing training with fellowships. It is a test that you prepare for throughout residency with didactics lectures and annual practice exams (in-training exams). Attendings are constantly preaching important clinical information on rounds, typically using the phrase, “this will definitely be on your boards.” As a chief medical resident, I have found myself spouting board-style questions to start off our morning reports and often using that same phrase to enforce the importance of this information to interns and residents.

Despite the significance of this exam to our training, I can’t help but wonder why this test alone is used as a judge of my capability to be a “Board Certified” physician. Having recently taken the exam, I believe the content is reasonable, but the truth is that no 240-question, multiple-choice exam can reflect all of the knowledge that is truly required to practice Internal Medicine. Most medical situations with real patients are not as simple as choosing a single answer. The clinical decision-making that goes into a case of a patient who is presenting with inconclusive work-up is much different than the characteristic cases seen on typical board exams. Most patients don’t present with the key words or pictures we learn to associate with different diseases. Far beyond knowledge alone, the communication and art of medicine is certainly not measured by selecting letters on an exam.

Admittedly, there is no perfect way to assess this knowledge for physicians today. Now more than ever, we actively rely on resources to look up information that we haven’t memorized and to collaborate across specialties to coordinate care. At the same time, it is appropriate to have some type of standard for a knowledge base that is important for trainees. Despite much criticism (and I haven’t even mentioned the cost!), board exam scores are important for obtaining and keeping positions as well as conveying to the public that we are appropriately trained and certified for our positions. However, I can’t help but wish this assessment of knowledge could be focused on clinical care of actual patients rather than selecting answers to a hypothetical situation on a computer.

I would rather housestaff learn how to deal with the reality of clinical uncertainty in medicine than memorize Reynolds’ pentad or how to treat babesiosis. I would rather have patients truly trust in residents and understand their explanations of the risks and benefits of anticoagulation than have them memorize the coagulation pathway. Despite the reality of standardized tests, I hope to frame knowledge to students and residents as important to the patient care they provide and not simply because “it will be on your boards.” Even with an always looming exam, there is a lot more to medicine than choosing A, B, C, or D.

August 22nd, 2016

First Week On Service

Joseph Cooper, MD

Joseph Cooper, MD, is a Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pennsylvania.

“Medicine Purple is now rounding at Room 202.” The announcement rang throughout the hallways on the lower pavilion. It was an announcement I had heard many times before, but this time it was quite different. As I glanced in the upper right hand corner of the electronic medical record of my first patient, the following glared back at me in all capital letters: “ATTENDING: COOPER, JOSEPH DAVID.” I had imagined the transition from resident to attending would be quite easy. I was in for a shock.

The first month of my chief residency had been primarily administrative, and I found myself becoming more frustrated and going home upset and with a short fuse at times. But not in my wildest dreams could I have imagined the responsibilities surrounding the role of being the Attending Physician of record. Everyone looks to you for answers: my team, including medical students, interns, residents, pharmacists, nurses, and ancillary staff, and, most importantly, patients and their families.

But this week — my first week on service — reaffirmed my passion for clinical care and my ultimate goal to become a clinician-educator. At first, I was unsure about my teaching abilities. But teaching, whether formal or informal, occurs at all levels of training, and I threw myself into it. I was surprised to find that I could deduce out how much or how little my team knew by simply asking questions and waiting. Ask the medical students first, and if they don’t know, move up to the interns, then the residents. I reminded myself to ask in a nonconfrontational style and engage every learner. Asking questions is an art rather than a skill and even the most experienced and knowledgeable clinician-educators can refine and improve upon it.

The highlight of my week on service actually occurred on day 1. An older gentleman with multiple comorbidities was admitted to the special care unit with septic shock secondary to gram-positive cocci bacteremia. He had progressively declined in the last few months secondary to vascular surgeries and postop complications. A family discussion was held after admission, and he was made a No Code (DNR). Throughout the night, his blood pressure became more tenuous, and his peripheral phenylephrine requirements continued to increase. The intern approached the patient and his family at bedside and explained the need for a central venous access to continue the higher doses of vasopressor medication. Neither the patient nor his family wanted any further invasive procedures, and they decided against the central venous catheter.

I arrived early in the next morning and sat down with the family and the patient. We talked about his previous occupation, what he did for fun, how many children he had, and even about his pets. The patient was ready. He said, “Doc, thank you for everything, but I want to be comfortable here with my family.” After my patient passed, his son had tears in his eyes. He pulled me aside and said, “I appreciate everything you did and the time you spent with my family and my dad. Thank you.” I was humbled and appreciative and couldn’t hold back my own tears.

As trainees, we forget sometimes about the human aspect of medicine and why we went into medicine in the first place. Throughout our training, we sometimes become blinded by money, prestige, burnout, and other extenuating factors and forget that, ultimately, we are here to take care of patients. And not only our patients themselves but also their families and close friends.

The next time you feel overworked, burned out, stressed, upset, or anxious on the job remember why you went into medicine in the first place. To help others. Sometimes we just need a simple reminder that this is one of the most exhilarating and gratifying careers in the world. Embrace it, love it, strive to improve, be human, be good to yourself and others. All in all, I have to say this has been a great “first week on service.”

August 19th, 2016

#OrlandoStrong #EndGunViolence

Kashif Shaikh, MD

Kashif Shaikh, MD, is the 2016-17 Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at the University of Central Florida College of Medicine.

I will never forget Sunday morning, June 12. I was off that day. I usually sleep with my cell phone on silent mode, and I slept late after binge watching some movie marathon the night before. I was still half asleep when I picked up my cell phone to see what time it was — but what I actually saw on my phone was a jumble of texts from friends and loved ones. I knew instantly that it wasn’t a good news. I opened the first text from a friend: “Are you okay? I am worried about you. I am very sad to hear about Orlando.” I thought at first that my friend was referring to Christina Grimmie’s heartbreaking incident, in which she lost her life at an Orlando concert. But that didn’t seem right — my friends wouldn’t be worried about my personal safety in relation to that event.

I had to swipe my phone for some news. The news that I read will haunt me for the rest of my life. The feeling that I had reminded me of the dementors that J.K. Rowling describes in her book. For the very first time, I understood the meaning of soul-sucking creatures. I felt as if every happy feeling literally was sucked out of my soul.I turned on the TV. I was in a state of shock. I was in denial. I thought that this couldn’t be real, that this was just a nightmare, and that I was probably still asleep. It couldn’t be happening here. But, no, it WAS real. I lost my appetite. I couldn’t sleep well for the next few days.

I watched Anderson Cooper’s coverage on the news. He was saying the names of the people who lost their lives, one by one. It was the most heartfelt coverage I have ever seen from a television journalist. It took me back to the tragedies of Sandy Hook, Charleston, and San Bernardino.I am still very upset when I think of how anyone, any lunatic, can buy guns without a background check. Right after the Pulse incident, when I stopped at a gas station, I saw advertisements for gun shows. Gun sellers were trying to take advantage of this whole situation. It was shameful. There was no respect for the victims who lost their precious lives.

![By Tony Webster from Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA (Stop Gun Violence) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blogs.jwatch.org/general-medicine/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/08/Stop_Gun_Violence_Sad_Face_Sign-300x200.jpg)

By Tony Webster from Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA (Stop Gun Violence) [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Gun violence is a public health issue

The morbidity and mortality associated with gun violence is a serious problem. In a 2014 paper by Braga et al. about focused deterrence on the prevention of gun violence, the authors stated, “Public health researchers and practitioners have historically prevented many deaths and illnesses by applying public health’s fundamental problem-solving capacity to develop actions such as water quality control, immunization programs, and food inspection regimes.”

In another review, from 2010, Narang et al. noted that access to guns affects risk for death and gun-related domestic violence. Narang et al. based their review on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, and Internet-based injury statistics: They found that high prevalence of guns is associated with high rates of suicide, accidental injury, homicide, and domestic violence. Suicide is the leading cause of death among gun owners in the initial years of acquisition. According to the authors, “Out of 395 fatalities occurring at a family home where a gun was present, suicide accounted for 333 cases (84%); 41 were domestic violence homicides, and 12 were accidents, while only nine were shootings of an intruder.”

Do guns make others safe?

Presence of a firearm in the home reportedly results in death or injury to household members or visitors over 12 times more often than to an intruder. Trauma centers receive many people with gunshot wounds said to be “accidents,” but circumstances in some of these cases indicate that they initially were stress-related shootings, done with an intent to die. Self-inflicted gunshot suicides outnumber both homicides and fatal accidents combined.As Narang et al. note, guns are the most commonly used weapon in domestic homicides, accounting for about 65% of all such deaths. Risk for intimate partner homicide is increased by fivefold. Gun ownership results in loss of life to women by suicide three times more often than where no such weapon is available.

The most remarkable statistic this review mentions is, “In 2005, it was documented that 5,285 US children were killed by gunshots according to data collected over a full year time period by the Centers for Disease Control; compare this to none in Japan, 19 for Great Britain, 57 in Germany, 109 in France, and 153 in Canada.”

This study also talks about how the consequences of gun-related violence, death, injury, disability, and/or dysfunction have a powerful effect on our society and healthcare system. Loss of loved ones, economic hardship, and psychological trauma is devastating. Bereavement compromises the quality of life, specially for children. It results in spread of fear in communities. It also affects medical costs, which indirectly affects the general population, government, and the healthcare delivery system.What is the cost?

According to Narang et al., “In 2005, approximately 30,000 Americans died of gunshots and nearly 70,000 received emergency treatment for nonfatal wounds. Emergency facilities are constantly burdened by the services required in such traumatic events. Medical care for these patients costs up to $4 billion per year. The overall economic cost due to these injuries in America, including healthcare, disability, unemployment, and other intangibles is about $100 billion per year.” This study also mentioned the case-to-fatality rate for gunshot trauma. It is about 30%, which is much higher than for other injuries. Death occurs following a shooting 18 times more often than after motorcycle accidents. Moreover, the hospital stays for patients with gunshot injury are in the range of nearly 2 weeks’ duration. The disability from such events averages approximately half a year. This affects taxpayers. Each homicide results in approximately $244,000 of incarceration expenses for our taxpayers.

In Kentucky in 2008, 73% of gunshot victims were uninsured, 10% were covered by government plans, and 17% were privately insured. Nationally, data reported in 2001 documented that government programs pay for about 49% of this amount, 18% is covered by private insurance, and 33% by all other sources.

Gun violence costs about 2.4 billion dollars annually to the criminal justice system in America. Local governments across our country spend up to $100 million each year just on bulletproof vests. Most of these bills are then passed on to the taxpayers. Why have no reforms been introduced after the mass shootings involving Sandy Hook, Charleston, and San Bernardino? What new laws could have potentially prevented the mass shooting at Pulse Orlando?

Gun violence costs about 2.4 billion dollars annually to the criminal justice system in America. Local governments across our country spend up to $100 million each year just on bulletproof vests. Most of these bills are then passed on to the taxpayers. Why have no reforms been introduced after the mass shootings involving Sandy Hook, Charleston, and San Bernardino? What new laws could have potentially prevented the mass shooting at Pulse Orlando?

The U.S. has the highest rate of firearm homicides amongst developed countries

With less than 5% of the world’s population, the United States has 35%-50% of the world’s civilian-owned guns. As of now, no federal laws ban semiautomatic assault weapons, military-style 0.50 caliber rifles, handguns, or large-capacity ammunition magazines. In fact, gun sales increase exponentially after deadly mass shootings. Everyone knows how easy it is to obtain guns in the United States in the name of the Second Amendment.

Japan which has the lowest firearm homicide rate (1 in ten million) in the world. Here is how Japan does it. Most guns are illegal, and ownership rates are low. Japan’s firearm and sword laws only permits shotguns, air guns, guns that have research or industrial purposes, or guns used for competitions. Before you can obtain such a weapon, you must obtain formal written instructions and pass a battery of written, mental, and drug tests and a rigorous background check. Furthermore, owners must inform the authorities of how the weapon and ammunition are stored and provide the firearm for annual inspection.

Then of course, there is an example of Australia’s Port Arthur massacre of April 1996, after which Australia prohibited automatic and semiautomatic assault rifles, stiffened licensing and ownership rules, and instituted a temporary gun buyback program. Since then, there have been no mass shootings in Australia.

Gun violence is a public health epidemic that is on the rise. The AMA has called gun violence a public health crisis. It vows to overturn a decade-ban on studying gun violence research by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The NRA opposed the assault weapons ban in 2013, because, according to CNN Money, “the organization’s overall revenue, which includes membership dues, program fees and other contributions, has boomed in recent years — rising to nearly $350 million in 2013.” According to a 2012 Forbes article, “Over 50 firearms-related companies have given at least $14.8 million to the NRA according to its list for a donor program that began in 2005.” In April 2016, Forbes published another article on the NRA. It mentioned, “The gun industry says it has grown 158% since Obama took office. The total economic impact of the firearms and ammunition industry in the U.S. increased from $19.1 billion in 2008 to $49.3 billion in 2015.” More than 17,360 American children and teens are involved in firearm-related injuries every year, and 111,779 people of all ages are hurt annually. One out of 3 homes with children contain firearms, and nearly 1.7 million children live in homes with at least one unlocked, loaded gun, according to the Brady Campaign.

I dedicate this blog to the victims and families of Pulse Orlando, Sandy Hook, Charleston, San Bernardino, and all other gun-violence related mass shootings in the world. I would like to end this discussion on a quote by Albert Einstein:

“The world is a dangerous place to live; not because of the people who are evil, but because of the people who can’t do anything about it.”

August 15th, 2016

Patient Education

Jamie Riches, DO

We had known Ms. B. for weeks. She was a “bounce-back” to the unit. Every day, an intern would enter the ICU room and ask, “How do you feel?” “OK.” Do you have any pain?” “No.” “Any trouble breathing?” “No.” “Tightness in your chest?” “No.” “No? OK.”

I was the senior resident following the case, 1 of 22 in the ICU. I walked in that morning and asked, “How do you feel? Are you nervous?” “Yes.” We’re trained as physicians to accumulate and analyze large amounts of information and condense it all into one-liners. I had known this patient as “a 74-year-old female admitted with acute hypercarbic respiratory failure in the setting of a large pleural effusion, atrial fibrillation with RVR, diastolic heart failure, and an extensive prior course complicated by an acute cardiac ischemic event, refusing catheterization.” That morning, the patient, whom I had also come to know as a dedicated mother, a strong-willed woman, and a funny, caring human being, was, in a one-liner, “tired and scared.” She was scheduled to have a thoracentesis that morning; we would remove fluid that had been occupying her lung space and test it for infections and cancer. We hoped the procedure would be diagnostic and therapeutic. She said she might not want to know if it was cancer. She just wanted to be able to go home. “We want that too, Mrs. B.”

Checklist: The patient was prepped in sterile fashion, and the area was cleaned and dressed appropriately. Risks and benefits were explained: check. A time-out was performed: Patient name—correct; Procedure—correct; Site—correct. Site was marked.

The patient sat at the edge of her bed with her arms outstretched across a rolling tray table. This was the table that usually held snacks, her small blue leather Bible, and the phone to call her son and daughter. Her children came to visit every single day and night. Today, the table held a plastic pillow, which crackled with the slightest movement. I squatted in front of the table and held her hands, while the fellow prepped for the procedure. “What procedure are you having, Ms. B?”, the attending physician asks. “They just told you. I’m having a thoracentesis.” “And what does that do? What is the purpose of the procedure?” “To take the fluid out of my lungs so I can breathe better.” The checklist was complete.

The patient sat at the edge of her bed with her arms outstretched across a rolling tray table. This was the table that usually held snacks, her small blue leather Bible, and the phone to call her son and daughter. Her children came to visit every single day and night. Today, the table held a plastic pillow, which crackled with the slightest movement. I squatted in front of the table and held her hands, while the fellow prepped for the procedure. “What procedure are you having, Ms. B?”, the attending physician asks. “They just told you. I’m having a thoracentesis.” “And what does that do? What is the purpose of the procedure?” “To take the fluid out of my lungs so I can breathe better.” The checklist was complete.

Ms. B held her small blue leather Bible by her side every day. She prayed and thanked the Lord every day she awoke to breathe. Despite 18 years of Catholic school, I probably haven’t “said my prayers” since I had to be reminded to take a bath.

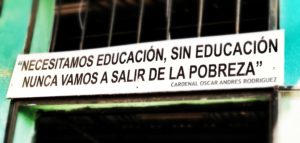

“Were you born in New York?”, I asked. “I was born in South Carolina. My mother brought me here when I was 2… to be educated. I was educated in New York City.” She spoke with a pride that not only filled me with a sense of gratitude, it fractured me with guilt. I too was educated in New York City. I had always regarded my education as an expectation, as opposed to a gift, despite neither of my parents having attended college. Knowledge was, to a certain extent, a collector’s item, to be acquired and displayed within various carefully chosen venues. My mother was hard on me when it came to my performance in school. If I scored a 98% on an exam, she would ask, “What happened to the other two points?” I had never been any more proud of my education than proud of my ability to wake up every day and brush my teeth. I’ve been reminded on more than one occasion that I do not have a “pedigree.” As an older African-American woman, Ms. B remembered a time when simply attending school was a right to be fought for.

“Were you born in New York?”, I asked. “I was born in South Carolina. My mother brought me here when I was 2… to be educated. I was educated in New York City.” She spoke with a pride that not only filled me with a sense of gratitude, it fractured me with guilt. I too was educated in New York City. I had always regarded my education as an expectation, as opposed to a gift, despite neither of my parents having attended college. Knowledge was, to a certain extent, a collector’s item, to be acquired and displayed within various carefully chosen venues. My mother was hard on me when it came to my performance in school. If I scored a 98% on an exam, she would ask, “What happened to the other two points?” I had never been any more proud of my education than proud of my ability to wake up every day and brush my teeth. I’ve been reminded on more than one occasion that I do not have a “pedigree.” As an older African-American woman, Ms. B remembered a time when simply attending school was a right to be fought for.

“I like your scarf,” I said. Ms. B wore a bold orange headscarf with an asymmetric bow. I’d seen her wear it many times over the course of her stay. There was something fearless about that scarf. Silence. “Are you nervous?” “Yes!” Silence. “What kind of music do you like?” “The Blues… and I love Christmas music. It just makes me happy.” I placed my iPhone on the tray table and opened a Spotify playlist called Christmas Hits. “I’ll Have a Blue Christmas Without You” was the first song. I made a joke about the song being best of both worlds. Silence. I found out during our conversation that she loved scary movies and zombie shows. “I love The Walking Dead, Night of the Living Dead, all those shows.” I told her that I can’t watch those shows because I am actually afraid of them. “They don’t scare me.”

Her hands were small. There was a cyst on her left little finger, which I hadn’t noticed before, any of the times I’d seen and examined her. I wondered what other observations I’ve failed to make. “Does this hurt?” “No.” “Has it always been there?” “No.” “What happened?” “I was carrying a heavy grocery bag, and it never went away.” When she felt discomfort or anxiety, she would quietly dig the tip of her fingernail into the pad of my gloved finger, staring straight into my eyes. I have the same self-soothing mechanism: I press the pads of my fingers, subtly and often subconsciously against the edges of my fingernails, bilaterally and symmetrically, until I’ve traveled from my indexes to my little fingers, and occasionally I’ll start the process over again from there. I usually don’t recognize my own nervousness until someone looks at my hands and says, “Are you OK?”

I whistled along to “Let It Snow” as the fellow continued with the procedure. The procedure was simple, “uncomplicated” as we say, no bleeding, no hemodynamic instability, no pain. Her son and daughter came in patting her on the shoulder, “You did great mom! See? You did great.” We all left the room to begin rounds. A post-procedure chest x-ray was unremarkable; decreasing pleural effusion, no evidence of pneumothorax. Ms. B spent the morning with her children and sister, breathing more comfortably. “She’s doing great!”

Later that afternoon, a nurse told me that the patient was having some difficulty breathing. When I arrived in the room, Ms. B’s heart rate was rapid and irregular. Simple breathing was laborious, and her face wore the expression of desperate fear. “Not the mask! No mask!” She had intermittently required a biPAP mask to support her breathing. She hated that mask. We thought the thoracentesis would alleviate its necessity. As I placed my stethoscope on the right side of her chest, I heard no sounds to accompany the arduous rise and fall of her ribcage. “We need a STAT chest x-ray!” The x-ray looked as if the image were split in two and inverted, as if the right side was a negative. Hemothorax. “She needs a chest tube,” the attending said.

As they prepared for a second procedure, I walked outside and placed my hand on her son’s shoulder. He was a large, loud, boisterous man who many of our staff members found intimidating. He had a plethora of very specific questions every day. The attending reviewed the new procedure with him, and he looked at me, timidly, with the same frightened eyes I had seen earlier that day. “Is she going to be OK tonight, Doc? I’m scared.” He previously had never called me anything but my first name. “What’s going to happen?” “I don’t know,” I said, “but we’re going to do everything we can to take care of her.” I walked away to the next room, to check on another patient, a “sick patient,” a GI bleeder receiving his 5th unit of PRBC repletion under our massive transfusion protocol. This was my education, my training as a physician, education that I was not always grateful for in the moment.

By James Heilman, MD (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

The last time I saw my own mother alive was in the ICU. We decided to place a DNR order before she died, knowing she wouldn’t have wanted anything more.

As the line flattened on Ms. B’s monitor, I knew the next series of chest compressions, shocks, and epinephrine pushes would be the last. “I’m running this.” Running a code had formerly been my most feared responsibility. I remember my intern year as if it were yesterday: chest compressions, running to the lab, grabbing the chart, being grateful to do anything except run the code. Throughout my training, this task has become like many others: systematic, ordered, implemented without difficulty. In this moment, I felt an enormous responsibility: to assure that we had done everything possible to give our patient and her family what they needed in that moment [for them to know they had done “everything”], to provide her the dignity she deserved in her death, to spare her from any excess undue harm, and to honor and care for her until her time of death. “6:53 PM,” I said, with final and deliberate certainty. Tears immediately filled my eyes and began falling in rapid succession as I stood, surrounded, witnessed by, the entire ICU team. The nurses rushed to the patient’s body to clean and dress her for the family to view. The family stood outside, intoxicated with fear, shock, and sorrow. “Let’s go,” one of my co-residents said, as she escorted me to the stairwell where, for a few sacred and uninterrupted minutes, I cried. I cried until it was time to wash my face, sign the required documents, and gather my papers for evening ICU rounds. “Check MR. F’s urine output overnight and dose the Lasix accordingly… Try to taper Mrs. C’s levophed…”

These are days where we not only experience but also participate in and often direct the most poignant moment of someone’s life; then, we move on with apparent simplicity. I’ve not had any more intimate experience than to learn someone’s history, wishes, and fears, to listen to her words, her breath, and her heart… to feel the contours of her hands, the fragility of her ribs, her fleeting pulse… and to witness her last breath.

I walked out of the hospital at midnight and, as I waited for a cab at the entrance, Ms. B’s family emerged, one by one: son, daughter, sisters, brother, in-laws… We hugged and cried. They told me they would take her home to South Carolina to be buried. “That’s good.” They thanked me for saying “I don’t know.” I said, “I’m sorry.” I was sorry. I am sorry for their loss, their pain, their mother’s suffering. I am also grateful to have had the experience of knowing her and her family, to have taken care of her, to have learned from her experiences, both good and bad… to have been changed by her gratitude.

Days later, I couldn’t stop thinking about this patient and how much she taught me. Although it felt strange, I googled my patient’s obituary. Among the many lines, it reads: She was educated in the New York City public school system.

August 8th, 2016

Smart Phones, Laptops, and Their Effect on Your Smartness

Kashif Shaikh, MD

Kashif Shaikh, MD, is the 2016-17 Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at the University of Central Florida College of Medicine.

“Please don’t spoil the movie with your own soundtrack.” Remember hearing this message before the beginning of a movie in a theater and how most people turn their devices on silent to watch the movie? The cost of the movie ticket is considerably less than the cost of medical education, but I wonder if learners consider this phenomenon when they walk into their classrooms. Is the habit of smart phones in our daily lives so engrained that we aren’t even aware of the distraction? Or is it that the learners get distracted unintentionally while they are looking for answers?

Recently, after giving several lectures to medical students and residents, I noted that most people in my audience checked their phones at some point. Noticeably, some attendees didn’t have their phones on silent and answered their phones while walking out of the lecture. People commonly check emails, browse the internet, and send text messages during lectures and meetings. Why are learners so distracted by technology, and what is its effect on learning?

I found a few papers on the effects of smart phones on learning:

- A 2013 study by Kuznekoff and Titsworth shows how mobile phone usage affects student learning. Researchers concluded that students who were not accessing their cell phones wrote down 62% more information in their notes, took more detailed notes, were able to recall more detailed information from the lecture, and scored a full letter grade and a half higher on a multiple choice test than those students who were actively using their cell phones.

- In another 2013 study by Sana et al., the investigators concluded that laptop multitasking hinders classroom learning for both users and nearby peers. The primary task was learning in the classroom, and the secondary task was completing unrelated online tasks. Notably, nearby peers scored even lower than the students who were multitasking.

Technology, of course, has pros and cons. Some of the pros: Most researchers in the education field talk about finding balance, wherein learners use technology to maximize their learning experience, form long-term memories, and acquire knowledge. Insight and awareness is always helpful and is the first step in technology etiquette. We also cannot disregard the value of technology in teaching (especially for disabled learners).

We need more research on this subject to examine positive and negative consequences, weigh the risks and benefits, and make an informed decision on the use of technology to maximize learning. What rules would you lay down for leaners on the use of smartphones, tablets, and laptops if you were teaching in the classroom?

August 1st, 2016

Four-Oh-Wunk

April Edwards, MD

April Edwards, MD, is the 2016-17 Chief Resident for the Internal Medicine/Pediatrics program at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine.

I’m April, and I’m the incoming PGY-5 Chief for the Internal Medicine and Pediatrics Residency in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Just last month, I had my 4th graduation from something since I finished high school.

Residency, it turns out, is long and hard. I’ve spent tons of hours practicing the art of sphincter control each time that I am the Code Team leader. I’ve done chest compressions and placed central lines in patients of all sizes. I’ve interpreted radiographic films on the fly and had innumerable conversations with families of critically ill patients when they are at their most vulnerable. I’ve had patients thank me, when I felt I didn’t deserve it, and others scream their frustrations at me, when I probably did. All of this is the experience you accumulate via the many lives with whom you intersect during residency.

What I seem to have missed in all of this, somehow, is becoming an actual grown-up. To re-frame, I effectively have just graduated from 24th grade. In some ways, it would seem that I have literally done NOTHING in life besides be in school/training. I am excellent at passing innumerable tests by the skin of my teeth, and enduring and possibly even thriving in increasingly intense environments on decreasing amounts of sleep. But I seem to have somehow missed the memo on how to financially “Adult.”

This was all been brought to my attention rather acutely during a so-called “senior pearls” session by one of my attendings at the end of last year. In it, she recommended heeding the advice of your Financial Adviser at this juncture and likely increasing both your Disability Insurance coverage and your Life Insurance. I glanced nervously around the room at the faces of my peers as she said this, and I tried to comprehend the completely foreign phrases “Financial Adviser,” “Disability Coverage,” and “Life Insurance.” The attending might as well have been speaking Dothraki. (Also, as a public service announcement, apparently it’s not “Four-oh-Wunk”, it’s just 401k).

How did this happen? How am I able to be in charge of people’s lives, and of the lives of those they hold most dear, and yet seem to have no actual handle on how the fiscal world and personal finances work — for me or my patients. Don’t get me wrong — I have been trained well by incredible physicians and teachers. And our public institution prides itself in providing the highest level of care to all comers, regardless of context. I have been taught to have poise in myriad challenging situations and to keep my cool under pressure. I am even headed toward a career in Critical Care after my Chief Residency. (Hopefully. Someone, please read my ERAS application.) But it would seem that there are a few things that I missed in between my call shifts.

What does this mean for our current medical trainees? I am likely an extreme version of one flavor of missed information, but, in my new role as chief, I have become aware that this does not occur in a vacuum. Other trainees have similar or related difficulties in non-medical knowledge. Which gets at the bigger question — how do we address the “Hidden Curriculum” for medical trainees?

People who go into medicine are great with data. They can store it and interpret it. They are quick learners. But what are we missing? The hole in my personal knowledge has made me think about what most people expect a physician to know/do and about how physicians are expected to behave, and whether my training has adequately addressed all of those things.

Others have alluded in this Blogsphere, to the related, although distinctive, issues of Burnout and Professionalism. These are things that I anticipate become even more familiar now that I’m in a resident supervisory position. Examples: one resident can make vent changes based on a blood gas but is brusque, stiff, and distant while delivering bad news. One can efficiently put in orders for a PICC line and the appropriate accompanying antibiotics but be short or even blatantly rude to nursing staff. Another always remembers to have her patients fill out PHQ-9s at their clinic appointments but fails to recognize the signs of depression/anxiety in herself that affect her own work.

All of this is to say, although residency training has certainly evolved since the Flexner report, we still have a lot of work to do. As I transition from residency to my next chapter, I am trying to be more attentive to this problem. The QI initiative posters I previously skipped because they weren’t about “science” are the ones displaying the work of people trying to combat this from the inside. We have to start early. These topics aren’t things we can cram into a module to be completed in between your OSHA certification and lunch. Nor can they be expected to be taught entirely before residents enter the “real world.” These are things that matter from the beginning and they must be taught from the beginning.

July 15th, 2016

What Is Resilience?

Jamie Riches, DO

NEJM Journal Watch is happy to welcome a new panel of Chief Resident bloggers for the 2016-2017 academic year. Here’s a sample of what our new bloggers will be discussing, starting on August 1!

Jamie Riches, DO, is a 2016-17 Chief Resident in Medicine at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

“Resilience” is defined as the capability of a strained body to recover its size and shape after deformation caused especially by compressive stress.

On March 9, of this year, my colleagues (my friends) and I unclipped our pagers from our belts, scrub tops, and white coats to read, en masse, “Important announcement at noon conference today.”

At that noon conference, we found out that one of our fellow residents had committed suicide by jumping from the hospital housing building. This intelligent, dedicated, accomplished young physician was the third internal medicine resident in our 22 square mile city to perform this act with identical detail in just under 2 years. We were dismissed to return to our pagers.

We picked ourselves up, literally, from sobbing piles on the bathroom floor and answered our pages. The work did not stop.

Throughout the following days and weeks, we were offered grief counseling sessions and open forums during noon conferences, where we could discuss our feelings and reactions. One morning, we were given free breakfast. We received many emails detailing these logistics, often ironically referred to as “housekeeping” items by the administration. We were desperately trying to clean up our own mess. The work did not stop.

Throughout the following days and weeks, we were offered grief counseling sessions and open forums during noon conferences, where we could discuss our feelings and reactions. One morning, we were given free breakfast. We received many emails detailing these logistics, often ironically referred to as “housekeeping” items by the administration. We were desperately trying to clean up our own mess. The work did not stop.

After more than 3 weeks of waiting for the institutional silence to be broken, we were again called to an important noon conference. We were addressed by a senior physician lecturer. He spoke about depression and suicide, and how these things can often be inevitable, unpreventable. We were reminded that we are in a high-risk profession. A stack of handouts made its way around the auditorium, offering a prescription for resilience. We were advised to train ourselves to develop a positive attitude, to face our fears and find a resilient role model. This was followed by an anecdote, highlighting the speaker’s ability to receive terribly tragic news involving one of his family members and to walk directly into a patient’s room to resume work after hanging up the phone. The lecturer proceeded to present his research on resilience, largely based on studies involving military personnel and prisoners of war suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. Correlations were made between entering the practice of medicine and entering the battlefield.

As the lecture proceeded, I began to realize that the traumatic event to which we were referring was not only our colleague’s suicide, it was our residency training. Unfortunately, this is not a correlation with which I am unfamiliar.

The forum was then open. “Please share your thoughts, experiences… and let us know: What can we do?” What can we do?

After a long pause, one of our most highly respected senior residents spoke, expressing his frustration with the fact that we were expected to resume work minutes after being informed of this tragic and shocking event. He stated that the perception of needing anything more than to take a deep breath and simply get back to work as equivalent to weakness, in combination with the “fear of retaliation,” was likely why no one was saying anything in this forum. This was followed by a reminder from our program director that “some people were given time off, and some people are still taking time off.”

This was true. One or two people had taken time off. We were not yet aware of what the repercussions of this time off would be. One month prior to this event, our chief residents had sent email to some of the senior residents: “If you are getting this email, it is because you have sick days to pay back. Sick days need to be paid back before June 30 so the program can sign off on your 3 years of GME, so please pick up shifts when you can.” Any resident who had taken a sick day in the past year was instructed to find time to cover an extra shift in order to “pay back” the institution for allowing recovery time. I had a flashback to another mass email referencing recent lateness to an outpatient clinic shift: “These instances are deplorable… You will become that person whom people hate to work with because of your lack of professionalism. Don’t turn into that, there’s already plenty of them plaguing our health system and we certainly don’t need any more.” These words were sent from those chosen to be our advocates. A wise, seasoned (and resilient) mentor of mine once gave me this piece of advice: “The institution will never love you back.”

Despite these examples, I don’t consider my program malignant. Malignancy in residency training refers to those programs in which the residents are placed in a hostile working environment. Despite having rapid administrative turnover (four program directors and three medicine chairs in 3 years), we have administers who are generally open to addressing resident concerns and who attempt to make changes based on resident feedback. This larger issue is not institutional; it is systemic.

Despite these examples, I don’t consider my program malignant. Malignancy in residency training refers to those programs in which the residents are placed in a hostile working environment. Despite having rapid administrative turnover (four program directors and three medicine chairs in 3 years), we have administers who are generally open to addressing resident concerns and who attempt to make changes based on resident feedback. This larger issue is not institutional; it is systemic.

I pride myself on my resilience. I am a New Yorker. I watched the Twin Towers fall on September 11, 2001, knowing that my family members were inside, saving others’ lives and sacrificing their own. I shared the grievous guilt of every family member, not only acknowledging that it could have been me, but wishing it had been. When I was choosing my own career, my father sat me down at an old wooden table at Chumley’s Bar and asked me if I thought I was “too good for the fire department.” My fear of fire is one I chose not to face. During my first year as a physician, my intern year, I received a phone call from my mother’s husband, informing me that she was in the ICU, and it “didn’t look good.” My mother’s life was plagued by a series of self-inflicted illnesses, and its culmination was that of multiple organ failure and a series of failed and futile resuscitation efforts. When I got the phone call that “it was time,” I walked into one of my patient’s rooms and informed him and his family member that I would be gone from the hospital for the afternoon because I had something to take care of. The patient’s sister replied, “I’m sure you’re very busy and have plenty of things to do, but this is his life we’re talking about.” I’ve cried every time I’ve lost a patient, someone’s mother or beloved family member, ever since. I continue to reflect on my disappointment with the overwhelmingly accepted notion that our training — the apex of our years of education, the threshold of our careers as physicians — is a traumatic event unto itself. Although, I know, in some ways, this is inevitable.

We enter medicine as if we are walking into a sacred space: hallowed halls where hierarchical gods prevail and miracles happen… until they don’t. We spent thousands of hours staring at computers and making phone calls and answering seemingly incessant pages, attempting to address questions to which we may not know the answers. We struggle to balance quality of care with quantity of care. We carry the underlying responsibility for the most vulnerable, most intimate moments of many people’s lives. This can feel like both a blessing and a burden. We not only carry people’s lives in our hands, we feel responsible for their deaths. We are tested every single day. Our knowledge, our patience, our compassion, our skill, our determination, and our stamina need to be demonstrated, examined, and verified. We struggle to find ways to work within a system that often feels punitive for its own faults. It can be lonely. It can be exhausting. It can be traumatic.

The Intern Health Study, a longitudinal study of depression among interns nationwide, estimated that “suicide rates among physicians are something like 40 to 70 percent higher in males and 130 to 300 percent higher in women.” Statistical estimates state that as many as 400 physicians commit suicide every year. Three young men and women leapt to their deaths in one city, in 16 months. We are not experiencing a tragic event; we are experiencing a harrowing trend. What can we do?

“Our needs are our greatest assets. I’ve learned to give everything I need.” – Andrew Solomon

The quote above is from a TED talk that, for months, I watched almost daily during my commute. This quote and many others gave me a great sense of comfort when I was grieving, tired, lonely, insecure, and burnt out. Looking back on those words, I wonder if the sentiment itself, or my attachment to it, is a reflection of the pathological need of the physician to feel strong.

I stood up to speak, not yet aware that my emotional state was one in which anything less than an [administrative] offer to turn back time would be received as an insult.

The resilience lecture began to feel less therapeutic [albeit well-intentioned] and more like a venue for perpetuation and exacerbation of a culture that was in itself, the compressive stress. We were being trained like soldiers, in the wake of our fallen comrade, to go out and fight! Be strong! Our strength was being measured by our ability to silently struggle through whatever we were experiencing and get the job done. Admit. Discharge. Admit again. We were being given tools to obviate the natural human state of vulnerability. We were “tasking victims with the burden of prevention.” We were reminded to be proud of our ability to charge on. I ended my commentary by stating that we were using the language of an abusive relationship.

What can we do?

- Eliminate the word “burnout” from the lexicon: Not only does burnout minimize the severity of depression, detachment and (at extremis) suicidal ideation among healthcare professionals (HCPs), it implies that those suffering post-trauma have some inherent flaw or weakness that impairs their ability to remain functional. This mindset removes the onus from the system.

- End the stigma: Remove the question, “Have you ever sought treatment for any mental illness” from the job applications. We should encourage residents, physicians at all levels, and other HCPs to actively seek out cognitive therapy as we do vaccines or PPDs.

- Decide what graduate education is: If residents are primarily learners, we must protect their time and use it solely for educational (both clinical and didactic) purposes and not to provide underpaid labor to perform all tasks for which the hospital is at a loss, no matter how menial. If residents are employees, we must provide adequate pay for educational level, protect sick leave, and outline contractual responsibilities before enrolling in the agreement.

- Stop penalizing unwellness: Physicians and HCPs are as human as our patients. We are not immune to everything. There will be times when we will be ill, physically and emotionally. We will need time and space to heal.

- Structure the system in a way that minimizes fear of retaliation: If the person creating or enforcing destructive policies is the same person who needs to write the words “excellent candidate” on the letter of recommendation that carries the weight of your future career opportunities, your best and worst interests are one and the same.

- Embrace our own fallibility: Learn to be comfortable with imperfection. Let us have an equal respect for our accomplishments and failures. Employ mentors who set this example.

- Accept that medicine is not martyrdom: The work does not stop. Let it not deplete us. Let us take care of each other and ourselves and not give away everything that we need.

“Recover” is the key word in the definition of resilience. Physicians are intimately acquainted with the process of recovery; recovery is a process. I do believe we will recover from this event, although not quite restored to our original state. We can work together to implement changes to not only create, but demand an educational and professional environment of safety, wellbeing, and, ultimately, resilience.

June 24th, 2016

The Scam of Medicine

Ahmad Yousaf, MD

Ahmad Yousaf, MD, is the 2015-16 Ambulatory Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School.

“Oh no, she’s calling again.”

I look at the caller ID in the Chiefs’ office where I sit with one of my co-Chiefs. It is the Documentation Lady. Her call is as regular as BMs with C. diff: Profuse, excessive, associated with a lot of hot air and a bunch of crap, but inevitable. We play a quick game of rock/paper/scissors… I lose. I pick up the call. My voice changes to a sweet phone voice with a sprinkle of passive aggression and self-loathing for the coming 3 to 10 minutes of ‘issues.’

Resident A did not conclude his note with a proper attending ‘supervision’ requirement. In plain English, that means that the resident concluded his note with: “will discuss the case with attending on rounds,” instead of “the attending of record is Dr. X.” Seems like a small difference… because it is. Seems like minutia and a waste of time… again, because it is. BUT, the reality is, she is inarguably correct.

Resident B did not use the proper document title in the note that described the reason for the patient’s conversion from observation status to full admission (needs to stay longer). The resident did explain why the longer stay was needed… but selected the wrong note title. Does it affect patient care? No. Does it affect the resident’s medical education? No. Does it warrant a phone call from the dreaded Documentation Lady? Yes. Again, she’s right. She knows it. I know it. Everybody knows it.

So we do our derisory dance on the phone, and I express false frustration at the false incompetence of residents who are caring for sick and dying patients and who are being assessed on clerical skills. To beat a dead horse: The documentation lady is right. Her justification for calling me demanding corrections is also right.

This is an example of the additional skills a doctor MUST learn in residency to one day work efficiently (make money) for his or her hospital. You cannot bill an insurance company without exact documentation, because the insurance company has their own documentation hawks looking for reasons not to pay the hospital. And so the game continues.

The problem is that I never knew I signed up for this game. Most doctors never knew that their lives would have as much to do with note-writing as patient care-giving. In the words of one of my attendings, “Medicine has become a scam.” There is so much administrative garbage to navigate in most nonacademic positions that doctors appear to be doing less and less doctoring — engaging in less eye contact with the people who need us and spending more intimate time with our computer screens. The harsh truth is that, here at the end of my training, my keyboard is more worn out than my stethoscope — and that scares me. I am a pragmatist, and I know that money makes the world spin and that patient notes are what makes the register ka-ching. But I didn’t know it would so significantly affect my ability to get to the bedside.

The problem is that I never knew I signed up for this game. Most doctors never knew that their lives would have as much to do with note-writing as patient care-giving. In the words of one of my attendings, “Medicine has become a scam.” There is so much administrative garbage to navigate in most nonacademic positions that doctors appear to be doing less and less doctoring — engaging in less eye contact with the people who need us and spending more intimate time with our computer screens. The harsh truth is that, here at the end of my training, my keyboard is more worn out than my stethoscope — and that scares me. I am a pragmatist, and I know that money makes the world spin and that patient notes are what makes the register ka-ching. But I didn’t know it would so significantly affect my ability to get to the bedside.

My phone call ends with a semi-sincere, “have a wonderful day, I am sure I will be hearing from you very soon!” I stare at my co-Chief across the table, and I can see the empathy in his eyes. We laugh at the absurdity, and then he speaks an absolute truth, “Man, I wish I was as good at being a doctor as she is at her job.”

June 17th, 2016

My Last Day in Greece

Ahmad Yousaf, MD

Ahmad Yousaf, MD, is the 2015-16 Ambulatory Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School.

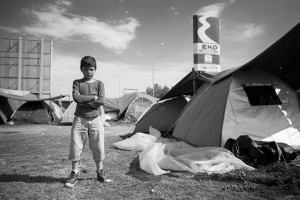

Reflections and observations from my last day in Greece as part of the SAMS (Syrian American Medical Society) medical mission for Syrian refugees:

1) It rained during clinic hours. It was a bit inconvenient for the team. For the refugees, it was catastrophic. Their tents, already damaged, allow the drops of precipitation to find their ways in and soak everything they own. They are drenched, their things are soaked, and there is no reprieve from the cold that follows. The rain puts out the fires they use to cook… to stay warm… to have some light when it gets dark. I have run out of negatively toned words in the English dictionary to describe the state of these human beings that could just as easily be me or you. I apologized a lot to them this week, on behalf of everyone. But to accept our forgiveness lies with them and God… and I cannot imagine how they could forgive us.

2) We met a man in his 30s, Greek, bearded, thin, a skipper by trade. He looked exhausted. He has no associations with Syria, Arabs, or Islam. He came to volunteer for 7 days — he extended to 10 days… then 14… then a month — that was 7 months ago. He lives here now, far from his home, among the refugees. He eats with them, sleeps close to them, and is engrossed in every aspect of helping them. As I was saying goodbye yesterday, I held his hands and told him he was a hero. He couldn’t look at me in the face when I said it, and I know he would never consider himself such. But that is exactly what he is.

3) As we left and said our goodbyes to the group we came with, I couldn’t help but feel like I was leaving family. One volunteer said, “I feel like I’ve fallen in love.” I agree — I have as well. I might never see most of them again, but I swear to you we are family forever.

4) In the video below you will see a Kurdish man, all alone, playing an instrument and singing a sad song, unaware of his audience. When he was asked why his song was so sad, he told us his story. He had sent his children ahead of him, and they now are in Germany seeking asylum. He was then separated from his wife who got stuck in one of the most war-torn areas of Syria, and he was only able to get as far as Greece. He now has run out of money and has been in the camp for months. Other refugees have given him some food and some supplies, but he has no money left. He cannot pay a smuggler to move him towards his children or pay for travel back to his wife in Syria. He feels as though he is the most alone man in the world. Indeed, he might be. May God help him find his way to his family.

5) Many refugees told us that they left, not for themselves, but because they didn’t want their children to see all of the dead bodies in the streets of Syria. The dead were purposefully left lying on the streets as a warning, and the killings occurred out in the open for the little children to see. One man had his wife and children with him and told us they almost made it past the Macedonian border when his wife had severely injured her knee while climbing through the mountains. She couldn’t go any further and had ordered her husband to take the children and leave her there by herself. She was going to die by herself, but at least she would know her children wouldn’t experience the horrors they had fled. The man couldn’t do it and instead had carried her to the Greek border and into one of the refugee camps. They were so close, but he loved her too much to leave her and had risked living in the camps forever so that they could stay together. Happy endings are few and far between for the Syrian people.

6) I did far less clinical work on this trip than my prior one because of the very fluid situation of the refugees. I feel like so much more needs to be done, but I am reminded of my most important role — to be a witness. To witness on behalf of Americans and on behalf of humankind. I will not ever be able to forget this problem exists. That there is an immeasurable amount of suffering among my fellow human beings and so many of us have ignored them. We have the blood of their misery on our hands (if not by direct action, then by apathy and purposeful ignorance), and the least we can do is acknowledge them, pray for them, and cry for them.

Video courtesy of Mayada Yousef

![By Justin Higuchi (https://www.flickr.com/photos/jus10h/15728670906/) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blogs.jwatch.org/general-medicine/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/08/Christina_Grimmie-236x300.jpg)

![By Crapuipui (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blogs.jwatch.org/general-medicine/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/08/Universal_CityWalk_Orlando_Panorama-1024x303.jpg)

![By Delphi234 (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blogs.jwatch.org/general-medicine/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/08/Children_and_teen_gun_death_rate.png)

![By VOA (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gAmr-A-F8K8) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blogs.jwatch.org/general-medicine/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/08/Sandy_Hook-300x201.png)

![AutoCCD assumed (based on copyright claims). [CC BY-SA 2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blogs.jwatch.org/general-medicine/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/08/Candles-300x200.jpg)

![By Jmaaks (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blogs.jwatch.org/general-medicine/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/08/GunViolenceVictimsComic-1024x724.jpg)

![Ferdinand Schmutzer [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blogs.jwatch.org/general-medicine/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/08/Einstein-228x300.jpg)