March 20th, 2017

Resident Wellness in Graduate Medical Education

Kashif Shaikh, MD

Kashif Shaikh, MD, is the 2016-17 Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at the University of Central Florida College of Medicine.

Happy Endings:

Living in Orlando, one cannot escape Disney. Disney movies are a delight, because one subconsciously anticipates that the happy ending is going to make up for the rest of the characters’ struggles. It works for me!

Be it Simba, Cinderella, Snow White, Belle, or Elsa, every Disney fairy tale gives us the desired ending of a happy and prosperous life. These characters go through many adversities, and new pages turn in their stories, but there is always a ray of light at the end of the tunnel.

So, without a predestined Disney ending, how do people in healthcare professions cope with the daily stress? For me, music and movies allow me to recover and recuperate. For others, the escape might be sports, arts, travel, music, family or social time, or something else that provides social support. Life is full of challenges and surprises, but it would be absolutely boring without any challenges, right?

The beginning of the story:

The first and the last day of medical school are unforgettable experiences for most of us. We are anxious, nervous, and terrified on day one, because we don’t know what the future will bring. But that last day makes up for it — we look back and smile — we have made it and can embark on our next adventure (residency).

As they say, success is not a destination. It is the direction in which one is traveling. First, let me describe my own situation: During the first month of my internship, I went through a big learning curve, like most of us do. (Just for context, I was in the last batch of interns who were allowed to work 24 hours shifts. When I became a second-year resident, the ACGME decreased the maximum work hours to 16 for the interns.) Long hours are stressful, even under the best of circumstances.

I have supportive family and friends, and I found a little group where I could share my problems and support others — bottling up frustration does not help! My colleagues gave me perspective on handling stressful situations or scenarios. As I advanced, my friends were one of the reasons that I looked forward to going to work every day. My biggest support groups during residency were my patients (who made me feel tremendously happy and fulfilled, because I was taking care of them), my colleagues, and my wonderful medical students. Healthcare is, no doubt, one of the most stressful professions. It requires utmost dedication. As residents, we make sacrifices in our social lives, like missing holidays with our families and our best friends’ birthdays and weddings. (Not to mention the obligation to work on presentations and research projects and to study for ITE exams and boards.) Residents must apply for fellowships and jobs after graduation. All of this happens at such a fast pace that we barely keep our heads above water. So how does one find a balance when one works so much and socializes so little?Achieving Resident wellness:

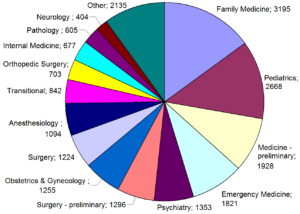

Most medical graduate programs struggle with promoting resident wellness. In a 2016 systematic review by KS Raj, resident well-being was lower than that in the general population (J Grad Med Educ 2016; 8:674). Notably, PGY1s reported less satisfaction with their lifestyle than did PGY2s and PGY3s. However, the reviewer also noted that resident autonomy, competence, and social relatedness was associated with greater resident well-being:

- A sense of control and autonomy

- Pursuit and achievement of goals

- Opportunities for learning

- Confidence

- Increasing mastery of techniques and interactions

- Positive feedback

- Positive colleague relationships

Sleep is another important factor in resident wellness. Residents who were not sleep-deprived reported better well-being. Residents with more personal-time availability for activities such as exercise, socialization, and errands were more likely to report positive residency experiences and positive emotions. Being in a relationship was associated with overall improved well-being.

Residents identified their well-being as affecting relatedness (specifically, the quality of discussions with patients and interactions with colleagues), competence (performance and decision-making), and autonomy (motivation with both daily work and career).

In a 2017 JAMA analysis, Shanafelt et al. found greater mental well-being to be associated with greater empathy in internal medicine residents. Also, ITE scores and academic success has no correlation with well-being (JAMA 2017; 317:901). Interventions such as faculty meetings at scheduled intervals to discuss progress and goals did not improve resident well-being or decrease burnout rates.

Should residency programs implement wellness programs?

According to Raj, residents who are most likely to participate in wellness programs are those younger than 32, females, and whites. Men more often question the utility of participating, whereas nonwhite residents are more likely to be concerned about confidentiality. Other factors associated with not utilizing a provided wellness program are a feeling of helplessness and perceived stigma.

As I was surviving my intern year, I promised myself that I would help my interns and medical students. I told myself that I would support them, that I would create a nurturing environment for learners and treat them not only as my colleagues but also as my comrades and friends. I would encourage them to share their problems; I would give counsel and guidance and support. Now, I’m a Chief Resident and I’m trying to keep my promises I made to myself. I try to make sure my interns and students don’t have to go through the difficult times alone.

By Clever Cupcakes from Montreal, Canada (Doctor Themed Cupcakes) [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

My recommendations to Chief Residents and residency programs:

1. Provide and ensure resident autonomy, competence, strong social relatedness, adequate sleep hours, and time away from work.

2. Encourage and promote perseverance, which is predictive of well-being, and greater well-being is associated with increased resident empathy.

3. We don’t yet know which specific interventions enhance residents’ well-being. Therefore, wellness committees from different programs should create a forum wherein they can share strategies that have been effective.

4. Provide third-party counselors to avoid stigma from seeking counsel.

5. Form support groups, where people can share their own experiences and provide support to others.

6. Organize more social events and group activities for team building.

7. And, most importantly for all of us: Look after your colleagues and friends, including medical students.

Please feel free to share any intervention that has improved well-being of residents in your program or anything else that you think might help.“Health is a state of body. Wellness is a state of being.” — J. Stanford

February 24th, 2017

Z71.1: Worried Well

April Edwards, MD

April Edwards, MD, is the 2016-17 Chief Resident for Internal Medicine/Pediatrics program at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine.

I took my dog to the vet today. You’d think this would be a straightforward sort of thing for a medical professional. You’d be wrong.

When I woke my dog up at 5:15am (my new daily start time, as it’s apparently the only way I can find time to do board questions, and is also the excuse I use when I miss the majority of said questions), he seemed sleepy. He’s a really hyper, ADHD-type dog, so slowly slunking about was not his usual M.O. Despite my rational patient-assessing abilities, I naturally assumed he had cancer and checked his lymph nodes and examined his poop. I stuck my stubby “people” otoscope in his ears desperately looking for otitis. No dice. He was still sluggish even after being more awake, so I took him in to the vet’s office at their earliest appointment today. Where I then proceeded to be the worst patient ever.

Nurse: “What seems to be wrong?”

Me: “He’s just not right.”

Nurse: “Why do you think that?”

Me: “I mean, he’s peeing and pooping fine, and can still walk and chase balls and stuff. He just seems not right.”

Nurse: “…..” (*uncomfortable eye contact*)

Nurse: “Okayyyy. Well, what medicines does he take?”

Me: “Just the regular stuff.”

Nurse: “Flea, tick, and heartworm protection?”

Me: “Yeah. The regular stuff.”

Nurse: “Which brand?”

Me: “You know. The kind in the red box. The red box from PetCo. I mean PetSmart. Or is it PetCo?”

Nurse: (*protracted sigh*)

I consider how I must sound to her, and I laugh out loud. The nurse continues to stare. But now that I’m laughing at myself, I think I’m funny, and I decide to continue my roll …

Nurse: “What kind of food does he eat?”

Me: “It’s in a blue bag.”

Nurse: (*staring*)

Me: “You know — it’s little brown pieces.” (*bursts into giggles*) “Sorry, couldn’t help myself. “

Anyway, after getting through the triage questionnaire, the vet checked out my dog, rectal temp and all. He’s fine. Completely and totally fine. But I’ve become one of the patients I sometimes see in my clinic. And I know, without a doubt, that the ICD-10 code is Z71.1: Worried well.

I need these moments. These times of transposition where I am reminded what it feels like on the receiving end of a stethoscope. How, despite having a smart watch, I am not adhering to a diet and exercise plan of which anyone would be proud. And even though Zyrtec reliably helps my seasonal allergies, I can’t seem to be bothered to remember to take it every day, and then tell colleagues how my allergies aren’t well controlled. How the morning after I eat beets, I temporarily think I have renal failure. Every time. And a thousand other examples, some scary and serious, others mundane. Examples of being human.

My patients remind me of my own humanity.

Residency isn’t easy. But it doesn’t have to be quite so hard. Explore NEJM Resident 360.

January 13th, 2017

Ganbare

Jamie Riches, DO

“May I never see in the patient anything but a fellow creature in pain.”- The Oath of Maimonides

I am not immune to the post-election frenzy. Never in my relatively short life, nor in my even shorter existence on social media, have I seen people so divided. Shortly after the president-elect was named, I found myself wondering, “Are you one of us, or one of them?” I had to sit myself down and ask what that even means… I am no party loyalist. I am an American. I voted for a candidate who I thought represented my fundamental values, and against a candidate who has incited a furor with which my values do not align. It occurred to me that most Americans have made the same decision, with varied outcomes.

Spoiler alert: I didn’t vote for Donald Trump. I spent a good few days wondering how anyone could. I stayed quiet — a passive observer of Facebook and Twitter. I watched as documented hate crimes filled the news, as people’s relationships became publicly strained. I told my dad that I was “heartbroken” after the election, and he said, “Why? I couldn’t stand her.” He was one of them. We quickly changed the subject. My dad is probably considered an “uneducated white male,” when it comes to polling stats and media representation. My father doesn’t have a medical degree, or even a college degree, but he has a knowledge base and skill set that allowed him to perform a job that I am not capable of. He’s a retired New York City firefighter, along with his brothers, his nephews, and my mother’s cousins and their sons. He’s a smart guy. They all are. They’re good men. They do good work. I started to dissect the term “uneducated” and even become offended by it. I moved into a new apartment last week and hired a team of people to help me disassemble and move furniture. These were probably “uneducated” or “working class” people, who again were able to do a job that I simply could not. Their education, their training, is different from mine. Their electoral decisions may (or may not) have been different from mine. We are people. We are Americans. I am part us and part them.

As I frantically refreshed my Facebook feed, I continued to come across divisive language. The same people who think Matt Maloney has no right to ask his employees to resign if they disagree with his criticism of the president-elect think it’s OK to ask people to leave the country if they disagree with their religious views and vice versa. I thought about my own workplace and what it would mean to allow such discrimination (on either end of the political spectrum) to prevail.

I work at a major cancer center with more than 10,000 employees. My colleagues, of all races, religions, nationalities, genders, sexual orientations, political affiliations, all come together day after day for the same cause: to conquer cancer. Period. Patients come from all over the world to be seen by experts in their disease. We do not ask, “To whom do you pray?” as a part of the history and physical. We do not ask, “To which government are you loyal?” We treat, we care for, we heal. We fight for our patients’ dignity throughout their illnesses and at the end of their lives. We stand with them and their families. We share their hopes and their fears. Their successes are ours to celebrate and their failures are ours to grieve.

People in the world are scared right now. Those who are scared now felt safer on November 7th, and those who were scared on November 7th feel safer now. Fellow creatures in pain. As I was driving to work the other day and quite honestly, musing on the election results, I noticed a sign that said, “Hill blocks view.” Therein lies the metaphor: We see the worst parts of ourselves when our security and our stability is threatened. I’ve experienced this first-hand. We, as physicians, preside over what are often the most terrifying moments of people’s lives. Our job is to understand and clarify those fears and to mitigate any exacerbating factors. We do not dismiss them as fabricated or unfounded. What would it look like if we did? What if societally, we adopted this principle of “selective tolerance” and how would it affect our immunity?

My grandfather-in-law, a Japanese-American (who had never even visited Japan), spent a number of his formative years interned in a camp after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Could this happen again in our lifetime? I don’t know. Could my [same-sex] marriage be federally nullified? I don’t know. Am I overreacting? I don’t know, but the line between simply doing what is right and standing up for what is right has become more prominent. Grandpa Horii died at 92 years old, a successful architect, professor and artist, father, grandfather and husband, whose resilience and determination were nothing short of awe-inspiring.

I’m a big-picture thinker. I’m moved by systemic reform. I’ve been unable to wrap my head around the big picture lately, so I’m attempting to train myself to see smaller-scale… daily human interactions. My family, my profession, not my politics.

In his incredibly moving New Yorker piece called “Health Of The Nation,” Atul Gawande writes, “Our hospitals and schools didn’t suddenly have Reaganite values in the eighties, or Clintonian ones in the nineties. They have evolved their own ethics, in keeping with American ideals…The helping professions will stand by their norms… Our fundamental values — values such as decency, reason, and compassion.”

Ganbare is a Japanese term of encouragement, often likened to the American expression, “Hang in there!”

In the fight to preserve decency, reason and compassion, “ganbare,” my friends.

December 28th, 2016

A Reflection on The Hippocratic Oath

Kashif Shaikh, MD

Kashif Shaikh, MD, is the 2016-17 Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at the University of Central Florida College of Medicine.

Questions for young physicians:

Do you remember and recall the series of events that inspired you to become a healthcare provider? Are you satisfied with the field of medicine? Have you ever thought about your perceptions of healthcare before and after becoming a physician? Have you ever been a patient yourself? What attributes in our healthcare system do you wish didn’t exist or need to change?

After finishing my rounds in the ICU, I was speaking to one of our charge nurses. We were discussing the advent of electronic health records and charting and its effects on patient satisfaction. She has been a nurse at our hospital for more than 25 years. Her thoughts: She was able to chart effectively and efficiently before the advent of EMRs, and she was also able to spend considerable amount of time at the bedside speaking with patients. But now, she must meet the excessive demands of EMR charting, which are strictly enforced. This has led to a decreased amount of time spent at the bedside with patients.

Patient satisfaction scores and charting are key determinants in hospital reimbursement these days. Insurance companies are the main driver in the relationship between adequate charting and hospital reimbursement. But the required “adequate charting” affects patient satisfaction scores in inadvertent ways: A frequent complaint that we hear from our patients is that the providers don’t spend enough time talking to them at the bedside!

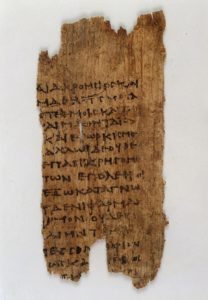

Papyrus text: fragment of Hippocratic oath. Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images (http://wellcomeimages.org). Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only license CC BY 4.0.

Here is he modern Hippocratic oath, to refresh our memories:

“I will remember that I do not treat a fever chart, a cancerous growth, but a sick human being, whose illness may affect the person’s family and economic stability. My responsibility includes these related problems, if I am to care adequately for the sick.”

I had another conversation, similar to the one I had with our nurse, with one of our senior vascular surgeons. He has been a surgeon for more than 30 years. He mentioned how he spends hours working on his daily progress notes on the electronic health record. We also discuss how much time is spent on charting in the U.S. compared with other countries. For example, in the U.K., charting is done specifically to document pertinent patient information, for the sole purpose of patient care, rather than to justify requirements of insurance companies for billing purposes.

Sadly, today, most providers at the hospital are busy charting and documenting patient care in front of computer screens. Providers go to great lengths to meet requirements for healthcare reimbursement, and most of them are under time constraints to complete their paperwork. They also put in orders electronically. These tasks directly affects the amount of time spent at the bedside talking to the patients. The components in the history & physical and progress notes mandated by the insurance companies require a substantial effort, and some of those requirements have no bearing on patient care.

I agree that EMRs are a more cost-effective and efficient way to track patient care than is paper charting. It is also an effective way to put in orders. But a universal EMR would save tremendous resources. But we need to define an effective universal EMR system for documentation and charting that targets patient safety, quality, and continuity of care. Those functions would allow us to do what healthcare providers need to do: Spend time at the bedside talking to our patients and their families (read: increase patient satisfaction). It would also foster good rapport between healthcare teams and patients.

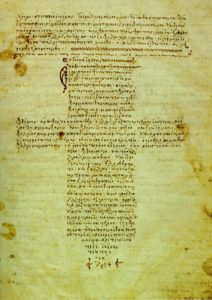

Foto de la Biblioteca Vaticana scan from book. User: Rmrfstar [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

I would like to end this article on the last paragraph of the Hippocratic Oath.

“If I do not violate this oath, may I enjoy life and art, respected while I live and remembered with affection thereafter. May I always act so as to preserve the finest traditions of my calling and may I long experience the joy of healing those who seek my help.”

Residency isn’t easy. But it doesn’t have to be quite so hard. Explore NEJM Resident 360.

December 22nd, 2016

“Pimping”: Malignant or Not?

Joseph Cooper, MD

Joseph Cooper, MD, is a Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pennsylvania.

One of the most respected and skilled clinician-educators (and, of course, he is an Infectious Diseases specialist) at our institute came into my office, sat down, and immediately starting eating pretzels. “Let me know what you think about this,” he said between bites. He went on to recapitulate a recent interaction he had with the members of the Internal Medicine team (medical students, house staff, and the attending physician) about a week ago.

He described a presentation to our emergency department of a young woman with headache, neck stiffness, and fever, who was previously well and had young children at home who were currently ill. He reported the lumbar puncture results to the house staff — the results included a mildly elevated protein level, normal glucose level, and pleocytosis with a predominance of neutrophils and monocytes. He then asked the house staff to formulate a differential diagnosis and explain their reasoning for said diagnoses. Later, he addressed the case again, and changed the values of the cerebrospinal fluid on the patient to clearly illustrate a bacterial source rather than a viral source, and he asked this question: “The pharmacist is standing at the Pyxis machine asking what medications to give. What are you going to tell her?”

Granted, I was not present for any of these interactions, but the vignette seemed more than reasonable to me. He was clearly trying to teach and have the house staff work through the differential diagnosis of deranged cerebrospinal findings — different disease states, offending pathogens, and treatment modalities. From the tone of his recitation of the events, I knew he was expecting a bit more than what he received from the house staff. He then asked me, “How do our residents learn today without being questioned?” I answered, “I’m not sure, but I’ve always found that questions are the best method.” The ID specialist left me with one last question: “Do you think I was too hard on them? Was I being a ‘malignant pimper’? Because I surely don’t want to be that.”

Frederick L. Brancati first coined “the art of pimping,” in his 1989 JAMA article: the practice of posing particularly difficult questions to learners. There are undertones in Brancati’s article (which is older than Justin Bieber) about the separation of power between the teacher and the trainee. Notions of respecting the teacher and expecting the trainee to follow the “chain of command.” Critics state that much of the article was written tongue-in-cheek, and it even prompted a response article twenty years later by Allan S. Detsky about learners taking back their power. Although each article illustrated differing approaches to pimping, they agree pimping confers some value to learners.

Wear et. al published a study in 2015 in which researchers examined interview responses from 4th-year medical students on perceived harms and benefits of pimping. The results were quite interesting, and although the cohort of medical students was not large (and no residents were included), many fundamental issues came to light. Students saw the value of pimping as allowing them to learn on their feet, develop the proper diction to speak with their colleagues, handle anxiety and pressure, and, ultimately, to motivate them to learn on the spot or later if they did not know the answer. “Malignant” pimping was identified by the students as situations in which the teacher was exerting hierarchical power, asking questions which were outside the scope for the learner (much too difficult), was buffering the ego of the teacher, or was simply humiliating the students by exposing deficiencies in knowledge rather than trying to create new connections.

Hugh A. Stoddard and David V. O’Dell made the ultimate comparison in their 2016 publication in Journal of General Internal Medicine, stating that psychological safety is the key difference between Socratic method of teaching and pimping. They defined the Socratic method as “prompting students, through cross-examination, into acknowledging their own fallacies and then asking them provocative questions to steer them towards realizing true knowledge via introspection.” The importance of psychological safety is highlighted when the learners feel they are in a safe environment, are comfortable with themselves and others, and feel valued and mutually respected without hostility and the threat of possible humiliation. The authors note that, even in a psychologically safe environment, Socratic teaching does not allow for a sub-par performance and that accountability is not a trade-off for the said safety.

This brings up a very strong and often overlooked point. I hear my administrators say all the time that residents should be more accountable. Accountability must be clearly defined and, at times in medical education, it is not. Sure, we have ACGME benchmarks and standards of what a “normal and average resident should be achieving by the time of independent practice.” At times, the sense of urgency and accountability seems to be lacking within the millennial generation. Learners expect to be spoon-fed lectures with important concepts and have protected time to learn those concepts, yet a very few seem to really possess that internal drive or accountability to own medicine, own the concepts, own the pathophysiology and disease process, and own their patients, because ultimately it is about their livelihood.

Returning back to the pretzel-eating, bow-tie wearing ID specialist’s question: Was he too hard on them? Was he being a malignant pimper? Although I did not witness the entire interaction, I would have to say no, absolutely not. I know he wants the house staff to learn, and he does not exhibit hierarchical power in his line of questioning, and he does not need to buffer his ego (he has won numerous teaching awards at our institution) or humiliate anyone. I offered him a morsel of constructive criticism, echoing what I’ve detailed above.

As I continue on throughout my chief year and move into fellowship, I must heed my own advice. Setting the stage and creating an environment of psychological safety is key when questioning learners. Numerous studies and evidence prove that posing questions at an appropriate level to the learner is the foundation to clinical reasoning and teaching, and we should not stray from this. Posing questions to our learners gives us a better understanding of their knowledge, their ability to explain concepts, and their deficiencies. The best clinician-educators take this information from their learners and expand on information that fills in deficiencies, or explain concepts in a way that the learners will never forget. Better yet, they motivate the learner to independently seek knowledge or skills they are lacking, with a continued thirst for learning.

Residency isn’t easy. But it doesn’t have to be quite so hard. Explore NEJM Resident 360.

November 4th, 2016

From the Prescription Pad to Reality

April Edwards, MD

April Edwards, MD, is the 2016-17 Chief Resident for Internal Medicine/Pediatrics program at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine.

A harsh reality I am coming to terms with, as a newly minted “pre-tending,” is that we don’t know the cost of the care we provide. There are recommendations for things like High Value Care, from organizations like the ACP. But how much do things actually cost? Certain apps and websites, like the Healthcare Bluebook, give you an idea of the cost of tests, procedures, and medications that you are ordering for your patients. But often, especially at hospitals like mine, public hospitals that serve many uninsured, under-insured, and Medicare/Medicaid patients, we encounter situations where patients can’t afford the services and medications that they need. I often find myself turning to sites like Good Rx to get coupons for patients, but, beyond this, the reality is that I don’t know where they can get affordable care.

I live in North Carolina, and I recently had a patient with presumed Rickettsial illness who was unable to afford doxycycline. I assumed this antibiotic was so basic and simple and been marketed for such a long time that surely it had to be accessible. But he wasn’t able to afford it. So how can we help? What tools are at our disposal?

Good Rx is one. If you type in a drug name, it will show you the pharmacies near the patient’s home that have that medication; the patient can compare prices at different pharmacies in the area. You can get printable coupons; you can print a voucher for the medication. We use the old standbys of the WalMart $4 list and the Target $4 list, and many medications are on those. Other resources exist, like Formulary Search, to tell you what is preapproved by a patient’s insurance. Remember all that prior auth paperwork? There are budding apps to help you with that.

But this is one of the things that we just don’t receive any training on during medical school and residency. I wish that it doesn’t matter — that “I’ll just prescribe the Best Therapy for my patient.” But I’m realizing that is a real struggle. In real life, if the benefit of the Best Therapy is something like 0.05%, but that Best Therapy is 10 times more expensive than the next best drug, sometimes it makes sense to recommend the one that is technically inferior but affordable. Because my patient will then actually be getting treatment.

It’s hard when your best intentions are met with a roll of red tape. It’s a real issue for all of our graduates fresh from residency. We are still shiny and hopeful. We haven’t become so jaded that we don’t want to Do Good. But we could use the tools to help us accomplish that.Post your favorite resources that help you Do Good! Help others to stop grasping in the darkness!

Residency isn’t easy. But it doesn’t have to be quite so hard. Explore NEJM Resident 360 now.

October 7th, 2016

Work Mimics Life: A Failed Attempt at Separation

Amanda Breviu, MD

As physicians, we generally attempt to separate our personal lives from our work. Some of this comes from modeling behavior of others during training, some comes with further experiences in coping with the patients we encounter.

I recently had the pleasure of caring for an elderly gentleman who was brought into the hospital by his loving wife and son. He had Parkinson disease, as well as dementia, and his family reported that his memory had declined considerably over the past several months.

I could not help but to be reminded of my own grandma — a fiercely independent and hard-working woman who had suffered her own declining health and memory recently — also as a result of Parkinson disease.

The family of my patient mentioned that, over the past 3 days, he had declined to the point of sleeping all day. When I first saw him, he was fairly somnolent but roused to voice, and he was not oriented to place or time. He referred to the nurse in the Emergency Department as his girlfriend, which his somewhat-embarrassed family members immediately apologized for. I stated that it wasn’t unusual for patients with memory problems to experience further confusion in a new setting.

I thought of my own grandmother, who had been unable to respond to questions without significant delay and effort, who at times could not remember all the names of her children who she dearly loved.

As we interviewed the patient further, he coughed on his own secretions; several minutes passed before he was able to breathe comfortably again. His wife noted that he had been doing that a lot during the past week. He needed oxygen now, although he never had before. I broached the subject of goals of care, knowing from chart review that the patient’s primary doctor had discussed this before. The grave expressions on the family’s faces conveyed their understanding of the severity of the situation. They looked at me expectantly. “Doctor, please tell us the truth about what’s happening.” The reality of the story — what his family members shared — was that he was in a stage of dying. Over the past several weeks, he had not been getting out of bed. He had not been eating or drinking, and he was losing weight. He could no longer safely swallow and was aspirating his own saliva.

I had recently watched my grandmother in these same stages. First, she could no longer eat bread, because she could not do so without risk of choking. Later, she could not go long without coughing on her own saliva.

The patient’s wife understood clearly when I conveyed his poor prognosis. She and her son did not hesitate when I discussed care options for their loved one; they immediately stated that they wished for him to be comfortable and not to undergo aggressive measures such as a feeding tube. His wife commented that “his life has not been living.”

Again, I thought of my grandmother. The gardening and quilting that she enjoyed so much during her life had become a distant memory by the end. My grandfather lovingly had visited her every day in the facility where she received hospice care.

Our patient passed away only a few days after I had met him. My grandmother had also passed away comfortably after receiving hospice care, only a few weeks prior. When I saw him, I saw my grandmother. When I saw his grieving family, my eyes filled with tears.

September 27th, 2016

Interview Season

Joseph Cooper, MD

Joseph Cooper, MD, is a Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pennsylvania.

It’s that time again — time to dust off your nicest suit and prepare for either residency or fellowship interviews. Being knee-deep in interview season for Infectious Diseases fellowships, my interview days bear some resemblance to my residency interviews, yet also are quite different. I have a unique opportunity this year to be a part of the recruitment and decision process for our internal medicine residency program, in addition to being a fellowship applicant.

I was visiting my cousins this past week, and they were baffled about my latest job search. “Matching” is a foreign concept to my cousins and to almost everyone else not in medicine. They asked, “So how was your interview? Did you get the job?” I started to describe the ERAS and NRMP match system: Filling out a centralized application (through ERAS), picking certain programs, accepting invitations for interviews, submitting a “rank list,” then having an algorithm determine where I will be working (while I wait with bated breath). I explained that I am interviewing at program XYZ now, and my cousins asked: “So, when does the position start?” The conversation that ensued was abruptly cut off by a crying baby in the next room. Probably for the best — it would have been a long conversation for the uninitiated. It is unique and unlike any traditional job application process. But, to be honest, it is an exciting and unforgettable time in the life of any medical student or resident.

Sure, last-minute plane tickets must be booked at an exorbitant cost, long drives in the rain on the morning of an interview are common, and pleading with your colleagues or program director to leave work a few hours early to make a pre-interview dinner is stressful. But all the students and residents who are going through this process now should focus on the long-term rewards rather than the short-term nuisances.When I think about my own residency interviews 4 years ago, I realize that some aspects of interviewing for a fellowship are similar, but some are much different. The structure of the day is essentially the same: pre-interview briefing/presentation of the program, one-on-one or group interviews, didactic presentations of some sort, possibly rounding with a team, a meal with current members of the program, and then a tour.

The one striking difference for me is the actual interviews themselves. During residency interviews, I felt like the interviewer hardly spoke and I was trying to “sell myself” to the program: Why I should be selected, why I would be a good resident, why I would fit in. For fellowship interviews, many of the programs seem to be selling their program to me. Many of the interviewers speak about their research or their experience as faculty. The “interviews” themselves are much more informal and are more like conversations. This caught me off guard initially, but I have settled into the pattern and become more comfortable.

For me, it has been an honor to meet and talk with some of the leaders in Infectious Diseases, because who knows if I will have opportunities for one-on-one conversations like these later in my career? To be on a conference call with one of the authors of the “ID Bible” and to talk about his area of expertise is humbling and intimidating. I have found it interesting to hear the opinions of these leaders on why the ID field has seen such a decline in the number of applicants (that topic I will reserve for a completely different post).

I wanted to leave you with some essential “dos,” and “don’ts,” for the interview trail, no matter what level position you are interviewing for. Many of these concepts seem like common sense; however, I have been unpleasantly surprised by the amount of “don’ts” I see from candidates we are hosting or from fellow colleagues on the interview trail. Have a great interview season, and remember to cherish these experiences — they are unique to our profession!

Do:

- Be engaged throughout the whole interview day.

- Be yourself — don’t pretend to be someone or something that you’re not.

- Be truthful.

- Know your CV and what is on it; be prepared to discuss any aspect of it. If you are not comfortable discussing something on your CV, it should not be present.

- Ask questions, but direct your questions to the appropriate person at the appropriate time.

- Practice and focus on your initial introduction or first impression with your handshake, eye contact, posture, and mannerisms.

- Be professional. It’s an ACGME core competency for a reason.

- Stifle your preconceived notions. Let the interviewer guide the conversation, but reinforce (truthfully) the strengths of your application to each interviewer.

- Give thanks and be appreciative. Write thank you notes (digital or via snail mail) afterwards.

Don’t:

- Be Late. There is no excuse for this — give yourself plenty of time and then double that estimate.

- Be distracted. Whether by your phone or some other item. Everyone from the institution is watching you in some way or another (even people you’d least suspect; not just faculty or residents and fellows).

- Be unprepared. Research the institution, your interviewers, and the current residents/fellows prior to the interview.

- Be unkempt. Your appearance is as important as what is coming out of your mouth.

- Fall asleep or be disengaged during a didactic or grand rounds. (See #2.)

- Wear wool suits. Perspiration is not your friend.

- Ask inappropriate questions. Do not ask the program director if the cafeteria is open 24 hours or where he or she lives.

- Provide answers you think the interviewer wants to hear. This goes back to #2 in Dos.

- Try to “one up” or be disrespectful to other applicants. They may be your colleagues come next year.

September 20th, 2016

Academic Near Miss

Jamie Riches, DO

I began one of my PGY2 medical oncology rotations alongside my co-resident: an MD/PhD, fast-track (pre-matched into fellowship) future oncologist. Among my three interns that rotation, two were “Harvard kids.” Needless to say, I was intimidated. My colleague and counterpart not only had the entire catalogue of genomic alterations at the tip of his tongue, he knew and understood their implications on disease. I saw my intern having a long conversation with a nurse at our patient’s door, and when I approached to see if there was anything I could do, I observed him giving a flawless lecture on the approach to an abnormal urinalysis and what really necessitates antibiotic treatment. I wasn’t really sure what I could add to this equation.

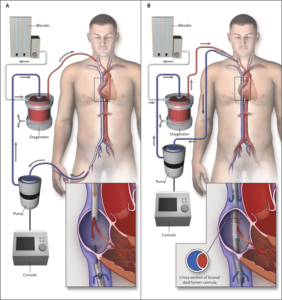

Over the course of the rotation, I found my place, and we all settled in to our roles. We learned from and taught each other different things. We had sick patients, and we took good care of them. When we felt like we’d exhausted all of our medical options to potentially reverse whatever underlying condition that we were attempting to treat, we would joke, “it’s time for ECMO.” When the joke began, I knew what ECMO was, but I didn’t really know how ECMO worked. I silently laughed along, certain that my co-resident and intern possessed superior understanding of this process and would lose all faith in my future contributions to the team should they become aware of my knowledge deficit. But, as we sat at the workstation one day, my co-resident opened Wikipedia and asked, “How does ECMO work exactly?” From there, the intern opened a series of diagrams and images, and we stood together, learning. I look at that experience as an academic “near miss.”

(If you’re curious about ECMO, read this.)

This experience is admittedly mundane, but it highlights one of the turning points in my career. I realized that, for years, I was embarrassed to read. The one piece of advice we’re given as trainees is “read more.” It is tattooed onto our physician-in-training souls. And I did read, but I had been reading “in private,” ashamed to admit that any knowledge deficit existed. I was convinced, each time I read, that I was looking something up that “I should already know.” And yet, there we sat for 5 minutes, looking up something in broad daylight!

I now know more about ways to learn. Working for 12 or 18 hours and attempting to absorb an article or chapter on the subway ride home is self-sabotage. “Spaced learning” is on the rise. Gone are the days of walking to the library to check out a stack of books. Medicine programs (such as my own), major journals, and academic societies “feed” you information via Twitter. We have infinite access to information in real time and limited time to access it. Despite our own aspirations for perfection, not having infinite knowledge is human. A piece of advice to interns and residents: Ask questions. Look up your own answers. Read more. Let what you don’t know motivate you. Being ashamed to acquire knowledge is a tragedy.

I now know more about ways to learn. Working for 12 or 18 hours and attempting to absorb an article or chapter on the subway ride home is self-sabotage. “Spaced learning” is on the rise. Gone are the days of walking to the library to check out a stack of books. Medicine programs (such as my own), major journals, and academic societies “feed” you information via Twitter. We have infinite access to information in real time and limited time to access it. Despite our own aspirations for perfection, not having infinite knowledge is human. A piece of advice to interns and residents: Ask questions. Look up your own answers. Read more. Let what you don’t know motivate you. Being ashamed to acquire knowledge is a tragedy.

September 12th, 2016

EpiPens Should Be Less Expensive

Kashif Shaikh, MD

Kashif Shaikh, MD, is the 2016-17 Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at the University of Central Florida College of Medicine.

This basic lifesaving medication is cheap to produce. It should not be a way to make a billion dollar profit. Should EpiPens be inexpensive and available? I say yes, and here are my reasons. I am not going to blame Shkreli or Bresch for trying to make money; it’s the system of silence and inaction that I blame. Money, power, corruption, and political influence are the key factors that allow big pharma and the individuals who run them to get free publicity and millions of dollars in their pockets.

Remember Shkreli’s arrest? He posted bail of $5 million within 24 hours. Yeah, the same guy who drove the price of Daraprim from $13.50 to $750 a pill had no problem coming up with $5 million in a day. Surprising? No.

Currently, Shkreli’s company, Turing Pharmaceuticals, makes the only FDA-approved pyrimethamine to treat toxoplasmosis. Even though the patent expired long ago, any company who wants to make a generic would need considerable time to go through FDA’s approval process. Silence and inaction on drug reform mean that patients are now charged 50 times more for their medication.

When Bresch’s company, Mylan, first bought Epipen in 2007, the price was around $50 for a single pen. Now, it has climbed to $600 for a pack of two! Epinephrine is not a new drug. It was first isolated in 1901, and it is not under patent. It is on the WHO list of essential medications, and the wholesale cost in the developing world is between US$0.10 and US$0.95 a vial. In Canada, Epipens cost around $102 (American) dollars, because Canada regulates drug prices.

The Epipen autoinjector is patented. But, how much does it cost to make an autoinjector? I mean, it is not made of gold or platinum! Now, Mylan promises a cheaper generic for the U.S. market. This is the recent trend in pharmaceuticals — to raise prices (“temporarily”) with a promise of a future generic. Everyone quietly pays the “temporary” higher price, because “the generic is coming.”However, the FDA takes a long time to approve generic medications and devices. Teva failed to obtain regulatory approval for its epinephrine-delivery device, and Sanofi recalled its autoinjector for incorrect dosage delivery. So Mylan alone sells Epipens and can increase the price without any competition. One might say that this is exploitation of a basic human need to obtain a life-saving medication — a medication that has been produced for almost 100 years.

Drug and device patents allow monopolies in the pharmaceutical industry: An average patent is enforced for 12 to 15 years. Although drug regulation obviously is important for patient safety, drug prices should be regulated, and approvals of generics should be prioritized. Right now, federal law prohibits Medicare from negotiating drug prices. We need legislation that limits the ability of pharmas to manipulate the system.There is no transparency in the drug manufacturing costs, and a recent analysis, reviewed by NEJM Journal Watch, suggests that development costs do not explain the costs of patent drugs (Why Do Prescription Drugs Cost So Much?). In reality, the silence and inaction around drug pricing allows pharmas to charge “whatever the market will bear.” It is unfair to the general public, because medicine is not a choice, but a need. Silence and inaction are unacceptable responses.

![By Jerry Berger [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blogs.jwatch.org/general-medicine/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/08/EMR-300x200.jpg)

![Clinic Painter [CC BY 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blogs.jwatch.org/general-medicine/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/08/AncientMedicine-300x270.jpg)