August 15th, 2016

Patient Education

Jamie Riches, DO

We had known Ms. B. for weeks. She was a “bounce-back” to the unit. Every day, an intern would enter the ICU room and ask, “How do you feel?” “OK.” Do you have any pain?” “No.” “Any trouble breathing?” “No.” “Tightness in your chest?” “No.” “No? OK.”

I was the senior resident following the case, 1 of 22 in the ICU. I walked in that morning and asked, “How do you feel? Are you nervous?” “Yes.” We’re trained as physicians to accumulate and analyze large amounts of information and condense it all into one-liners. I had known this patient as “a 74-year-old female admitted with acute hypercarbic respiratory failure in the setting of a large pleural effusion, atrial fibrillation with RVR, diastolic heart failure, and an extensive prior course complicated by an acute cardiac ischemic event, refusing catheterization.” That morning, the patient, whom I had also come to know as a dedicated mother, a strong-willed woman, and a funny, caring human being, was, in a one-liner, “tired and scared.” She was scheduled to have a thoracentesis that morning; we would remove fluid that had been occupying her lung space and test it for infections and cancer. We hoped the procedure would be diagnostic and therapeutic. She said she might not want to know if it was cancer. She just wanted to be able to go home. “We want that too, Mrs. B.”

Checklist: The patient was prepped in sterile fashion, and the area was cleaned and dressed appropriately. Risks and benefits were explained: check. A time-out was performed: Patient name—correct; Procedure—correct; Site—correct. Site was marked.

The patient sat at the edge of her bed with her arms outstretched across a rolling tray table. This was the table that usually held snacks, her small blue leather Bible, and the phone to call her son and daughter. Her children came to visit every single day and night. Today, the table held a plastic pillow, which crackled with the slightest movement. I squatted in front of the table and held her hands, while the fellow prepped for the procedure. “What procedure are you having, Ms. B?”, the attending physician asks. “They just told you. I’m having a thoracentesis.” “And what does that do? What is the purpose of the procedure?” “To take the fluid out of my lungs so I can breathe better.” The checklist was complete.

The patient sat at the edge of her bed with her arms outstretched across a rolling tray table. This was the table that usually held snacks, her small blue leather Bible, and the phone to call her son and daughter. Her children came to visit every single day and night. Today, the table held a plastic pillow, which crackled with the slightest movement. I squatted in front of the table and held her hands, while the fellow prepped for the procedure. “What procedure are you having, Ms. B?”, the attending physician asks. “They just told you. I’m having a thoracentesis.” “And what does that do? What is the purpose of the procedure?” “To take the fluid out of my lungs so I can breathe better.” The checklist was complete.

Ms. B held her small blue leather Bible by her side every day. She prayed and thanked the Lord every day she awoke to breathe. Despite 18 years of Catholic school, I probably haven’t “said my prayers” since I had to be reminded to take a bath.

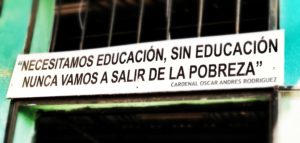

“Were you born in New York?”, I asked. “I was born in South Carolina. My mother brought me here when I was 2… to be educated. I was educated in New York City.” She spoke with a pride that not only filled me with a sense of gratitude, it fractured me with guilt. I too was educated in New York City. I had always regarded my education as an expectation, as opposed to a gift, despite neither of my parents having attended college. Knowledge was, to a certain extent, a collector’s item, to be acquired and displayed within various carefully chosen venues. My mother was hard on me when it came to my performance in school. If I scored a 98% on an exam, she would ask, “What happened to the other two points?” I had never been any more proud of my education than proud of my ability to wake up every day and brush my teeth. I’ve been reminded on more than one occasion that I do not have a “pedigree.” As an older African-American woman, Ms. B remembered a time when simply attending school was a right to be fought for.

“Were you born in New York?”, I asked. “I was born in South Carolina. My mother brought me here when I was 2… to be educated. I was educated in New York City.” She spoke with a pride that not only filled me with a sense of gratitude, it fractured me with guilt. I too was educated in New York City. I had always regarded my education as an expectation, as opposed to a gift, despite neither of my parents having attended college. Knowledge was, to a certain extent, a collector’s item, to be acquired and displayed within various carefully chosen venues. My mother was hard on me when it came to my performance in school. If I scored a 98% on an exam, she would ask, “What happened to the other two points?” I had never been any more proud of my education than proud of my ability to wake up every day and brush my teeth. I’ve been reminded on more than one occasion that I do not have a “pedigree.” As an older African-American woman, Ms. B remembered a time when simply attending school was a right to be fought for.

“I like your scarf,” I said. Ms. B wore a bold orange headscarf with an asymmetric bow. I’d seen her wear it many times over the course of her stay. There was something fearless about that scarf. Silence. “Are you nervous?” “Yes!” Silence. “What kind of music do you like?” “The Blues… and I love Christmas music. It just makes me happy.” I placed my iPhone on the tray table and opened a Spotify playlist called Christmas Hits. “I’ll Have a Blue Christmas Without You” was the first song. I made a joke about the song being best of both worlds. Silence. I found out during our conversation that she loved scary movies and zombie shows. “I love The Walking Dead, Night of the Living Dead, all those shows.” I told her that I can’t watch those shows because I am actually afraid of them. “They don’t scare me.”

Her hands were small. There was a cyst on her left little finger, which I hadn’t noticed before, any of the times I’d seen and examined her. I wondered what other observations I’ve failed to make. “Does this hurt?” “No.” “Has it always been there?” “No.” “What happened?” “I was carrying a heavy grocery bag, and it never went away.” When she felt discomfort or anxiety, she would quietly dig the tip of her fingernail into the pad of my gloved finger, staring straight into my eyes. I have the same self-soothing mechanism: I press the pads of my fingers, subtly and often subconsciously against the edges of my fingernails, bilaterally and symmetrically, until I’ve traveled from my indexes to my little fingers, and occasionally I’ll start the process over again from there. I usually don’t recognize my own nervousness until someone looks at my hands and says, “Are you OK?”

I whistled along to “Let It Snow” as the fellow continued with the procedure. The procedure was simple, “uncomplicated” as we say, no bleeding, no hemodynamic instability, no pain. Her son and daughter came in patting her on the shoulder, “You did great mom! See? You did great.” We all left the room to begin rounds. A post-procedure chest x-ray was unremarkable; decreasing pleural effusion, no evidence of pneumothorax. Ms. B spent the morning with her children and sister, breathing more comfortably. “She’s doing great!”

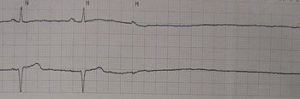

Later that afternoon, a nurse told me that the patient was having some difficulty breathing. When I arrived in the room, Ms. B’s heart rate was rapid and irregular. Simple breathing was laborious, and her face wore the expression of desperate fear. “Not the mask! No mask!” She had intermittently required a biPAP mask to support her breathing. She hated that mask. We thought the thoracentesis would alleviate its necessity. As I placed my stethoscope on the right side of her chest, I heard no sounds to accompany the arduous rise and fall of her ribcage. “We need a STAT chest x-ray!” The x-ray looked as if the image were split in two and inverted, as if the right side was a negative. Hemothorax. “She needs a chest tube,” the attending said.

As they prepared for a second procedure, I walked outside and placed my hand on her son’s shoulder. He was a large, loud, boisterous man who many of our staff members found intimidating. He had a plethora of very specific questions every day. The attending reviewed the new procedure with him, and he looked at me, timidly, with the same frightened eyes I had seen earlier that day. “Is she going to be OK tonight, Doc? I’m scared.” He previously had never called me anything but my first name. “What’s going to happen?” “I don’t know,” I said, “but we’re going to do everything we can to take care of her.” I walked away to the next room, to check on another patient, a “sick patient,” a GI bleeder receiving his 5th unit of PRBC repletion under our massive transfusion protocol. This was my education, my training as a physician, education that I was not always grateful for in the moment.

By James Heilman, MD (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

The last time I saw my own mother alive was in the ICU. We decided to place a DNR order before she died, knowing she wouldn’t have wanted anything more.

As the line flattened on Ms. B’s monitor, I knew the next series of chest compressions, shocks, and epinephrine pushes would be the last. “I’m running this.” Running a code had formerly been my most feared responsibility. I remember my intern year as if it were yesterday: chest compressions, running to the lab, grabbing the chart, being grateful to do anything except run the code. Throughout my training, this task has become like many others: systematic, ordered, implemented without difficulty. In this moment, I felt an enormous responsibility: to assure that we had done everything possible to give our patient and her family what they needed in that moment [for them to know they had done “everything”], to provide her the dignity she deserved in her death, to spare her from any excess undue harm, and to honor and care for her until her time of death. “6:53 PM,” I said, with final and deliberate certainty. Tears immediately filled my eyes and began falling in rapid succession as I stood, surrounded, witnessed by, the entire ICU team. The nurses rushed to the patient’s body to clean and dress her for the family to view. The family stood outside, intoxicated with fear, shock, and sorrow. “Let’s go,” one of my co-residents said, as she escorted me to the stairwell where, for a few sacred and uninterrupted minutes, I cried. I cried until it was time to wash my face, sign the required documents, and gather my papers for evening ICU rounds. “Check MR. F’s urine output overnight and dose the Lasix accordingly… Try to taper Mrs. C’s levophed…”

These are days where we not only experience but also participate in and often direct the most poignant moment of someone’s life; then, we move on with apparent simplicity. I’ve not had any more intimate experience than to learn someone’s history, wishes, and fears, to listen to her words, her breath, and her heart… to feel the contours of her hands, the fragility of her ribs, her fleeting pulse… and to witness her last breath.

I walked out of the hospital at midnight and, as I waited for a cab at the entrance, Ms. B’s family emerged, one by one: son, daughter, sisters, brother, in-laws… We hugged and cried. They told me they would take her home to South Carolina to be buried. “That’s good.” They thanked me for saying “I don’t know.” I said, “I’m sorry.” I was sorry. I am sorry for their loss, their pain, their mother’s suffering. I am also grateful to have had the experience of knowing her and her family, to have taken care of her, to have learned from her experiences, both good and bad… to have been changed by her gratitude.

Days later, I couldn’t stop thinking about this patient and how much she taught me. Although it felt strange, I googled my patient’s obituary. Among the many lines, it reads: She was educated in the New York City public school system.

What a fine article. Medicine is lucky to have you, Jamie. Thank you.

Thank you, Frank.

Hi Jamie,

Thanks again for taking the time and energy to write such an article. I’ve greatly enjoyed and responded to a couple of your previous articles, and this one, as expected, is right on point. You always seem to get to the very heart of issues that are very challenging and near and dear to my heart. Your article strikes a nerve because I can very easily see how we get sidetracked in medicine by the very system we are a part of, the efficiency by which we are supposed to see our patients, and as a senior resident like you, the “responsibility” you have to care for all of these patients and not let interns like myself miss important details on these patients. The challenge is, the expectations of “knowing” your 20-25 patients in the intimate detail that lets you treat them as human beings, not diseases that happen to be inhabiting a human shell can get to be more than a little much. Suddenly, in order to take care of this many patients, and not have a 1+ hour check out, we are forced to condense our patients into a one or two sentence diatribe that, as you point out, almost takes the entire humanity out of our patients. I get the purpose of this as well as any other person who’s been in medicine waiting to get to the punch line of a joke after a 2 minute diatribe, but I can’t help but admit, like you, that we miss something here, and sometimes I’d argue more than a little something. What you so nicely address here is the fact that this patient is something more than a person with a thoracic effusion who didn’t want a cardiac cath in her recent past; she is someone’s mother, an interesting woman with likes, dislikes, fears and insecurities. Sometimes I fear we miss this, or forget it while practicing medicine, at least how we “practice” medicine these days in a manner dictated by hospital policy, or what insurance will pay for, or ordering tests in the order they require so we can ultimately get that MRI which is what we wanted in the first place.

I agree with you that we must work within this system we are provided, but admire the ways you have tried to, and in my opinion, and kept the humanity in your medicine. May you never lose this drive!

On a separate note, I’ll tell you that I’ve personally struggled with some of the topics you brought up here very recently. I’m currently on a consult service and was asked to see a gentleman after a significant cardiopulmonary procedure. He seemed to be improving slowly but steadily; his BUN/Cr would bounce around a bit, but with some dialysis, he seemed to turn around and I thought we were beginning to make progress. We would talk to his wife daily about how things were going, what she thought he’d be able to tolerate on any given day, and then call it a wrap and go on to our next patients…Remember, we have a list of 20-30 patients, so who could spend so long on any one given patient??? Well, after being off for one day, I looked at my list to notice a name missing. Weird… Thinking he couldn’t have simply discharged in the one day I was gone, I asked a colleague, who like me didn’t know what had happened. After asking multiple people, I find out he had passed away the night before. After an extensive chart search (which has now been locked after his passing overnight), I was overwhelmed with emotion when I found out he coded overnight. Aside from me and my questioning, no one on the team mentioned him all day. I felt embarrassed, angry, bitter, but mostly ashamed that someone like this could pass away and my team, probably being so busy, treated him as if he had just “disappeared.” I was angry, because not being the primary team, I didn’t even know if the primary team had talked with his wife, and supported her, talked to her as the code unfolded as the tumultous end to his life. It made me feel completely unprepared for his death, and somehow responsible, wanting to make this horrible situation better, but I didn’t know how.

If I analyze it, I think this situation bothered me on multiple levels. I think we all fear not mattering to those around us, and thinking that life will just continue on in our absence, as if we weren’t that important anyway, and I saw this disaster unfolding before my very eyes. I couldn’t help but wonder if we physicians and caregivers were doing exactly what we thought we’d never do. When I talked to an attending physician the following day from another team, he simply said, “well the gentleman was old and this type of thing happens in the business.” I couldn’t help but see some truth in his statement, and acknowledged that he couldn’t be as emotionally riled up as I had been for this single patient for the hundreds of patients who had undoubtedly passed away under his care; how could he be? He’d never be able to carry on in his work on a daily basis and continue his work as a physician for the other patient’s who needed his skills, but I left feeling kind of empty, wondering if I’d ever become this emotionally empty shell of a physician just trudging though my daily work. I certainly still hope not. I just wanted his wife to know that someone, actually many people, really deeply cared for her husband and were sorry for her loss–was I the only one that could say this?

I’ll end with a final remark I remember from my English Literature studies in university before I entered medical school and began the path to thinking about human disease and suffering from the perspective of a history and physical, differential diagnosis, review of systems and a thorough physical exam. In a text we read about on how to become a better prose writer and on the intricacies of language, and why syntax mattered, the author reflected on where he had been years before. He had worked at a newspaper and was waiting for his “big break” into “important” journalism, but instead was offered his first job writing the obituaries. He felt it was a relatively unimportant and lackluster job that didn’t attract much attention until his editor talked to him one day about why he wasn’t performing at the level his boss thought him capable. He explained that he was disappointed not to be writing about front page news, or even the daily happenings around town, and that he was just itching for this opportunity. His editor took all he said in, and after a long silence said, “I was just like you once, but I’d like you to know you have a very important job right now. The pieces you write in the newspaper every day will be the most closely read, highly regarded pieces of literature you will ever write in your entire career. The pieces of art you write will be some of the last written word people will see about their loved ones who have recently passed away, and they will likely keep what you’ve written for many years to come.” The author said he left re-energized and with a new outlook on his job that influenced the rest of his career. I’d like to think that many of us in medicine are just like this man trying to find his way in his field, waiting for whatever is next around the corner, the next big break. But then I remind myself, we are meant to be where we currently are at. We are meant to hurt for our patient and their family when they are suffering, and when they have to say goodbye to their loved ones. My sadness may be, ironically, my very strength. We are really privileged to have the jobs we have at these important, and very personal times in other’s lives. I just hope we can think about it, and recognize just how lucky we are to be sentient creatures that in our hearts of hearts, want to help others. This part of the calling of medicine can never be extinguished even if we have 25 patients to see on our hospital rounds in one day.

Sean, thank you for the thoughtful reply. Well said! I love this quote (and can certainly relate): My sadness may be, ironically, my very strength. I think you should keep writing as well and continue to share these anecdotes!

Thanks very much for your reply. I bet your colleagues and underlings (as I call us underclassmen) are lucky to have you as a Chief Resident. You seem to be a great role model, and we can never have too many of those!

There is certainly a need for us in medicine to be able to express ourselves, both the joys and challenges of practicing medicine in the hospital world today. I think it is a valuable venting mechanism for all the things we see and experience on a daily basis, and an important way to process what it is we feel emotionally. Our job is not like many others that they can or do leave when they leave the office. Ours really does follow us home; we just have to find ways to cope with the actions we take, and the fact that sometimes things just don’t work out as we planned no matter our best intentions. There is a long history of physicians writing (William Carlos Williams, who was a Pediatrician and possibly IM doctor, Atul Gawande, Eric Topol, etc.) and I think it is a great, admirable skill to develop. It is also very important for people in the lay public to see some of our struggles as physicians and to “make us human again.” Only then will we stop seeing headlines in the news that people only check into hospitals to die, or that 1/7 people will contract a iatrogenic infection/error/experience harm, etc. when they are admitted. Sure, hospitals are dangerous places, but not places any provider intentionally tries to harm people. We operate in a complex and difficult world, and try to make the best decisions in a world that is full of shades of grey, and very little black or white.

Keep up the good work!

Sean

I’m not a physician. I just wanted to let you all know I understand how difficult it must be to get emotionally involved in your patients; I don’t know how you could continually function if you allowed yourself to feel with respect to each patient you treat. Having said that, I know of an oncologist specializing in breast cancer who cries in the hospital parking lot every time she loses a patient, and I will never forget her for that. I also had a father who suffered from Alzheimer’s. In one of his last hospital stays, a doctor told my mother if he ever got Alzheimer’s, he hoped he would be just like my father. (My father was the nicest man you could ever meet.) I never met the doctor but I will never forget him for that. Just know that even your small flashes of humanity are greatly appreciated and never forgotten by the families. Thanks to you all for everything you do.

Beth Clukey

Beth,

We greatly appreciate your comments and feedback. Sometimes I think we as healthcare professionals (Doctors, Nurses, PT/OT, etc.) do a poor job of expressing ourselves to our patients and their families. We too feel pulled in our tasks of rounding on umpteen patients on any given morning, writing notes, writing notes about our notes, and notating even the smallest changes in the care trajectory of our patients just so the next provider can “know” what’s going on. Most all of us really do deeply care about our patients and take it personally when things don’t go well. We see our mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, in our patients and I try to think about that each time I see my patients.

I may not be the fastest person to pre-round or visit with my patients, but I treat others as I’d like to be treated. Just know that many of us go about our days possessed by factors and care dictators far beyond our level of training–usually an insurance company or hospital utilization specialist who says what has to be done in what order. We simply get the opportunity to dig our heels in and advocate for our patients when we feel that will move us in the wrong direction. That said, you can’t go out swinging for every patient every single day otherwise the system will burn you out. Sounds like your father was a gem, and we love treating those types of patients; they bring great reward to the work we do!

Dr. Riches,

Your article is the must-read in this week’s “Top 5 Patient Experience Articles.”

http://ow.ly/X8RQ303oCvq

Thanks for sharing your experience in such a powerful way.

Susan, Thank you so much for the feedback on this article. I must have missed this comment until I was looking through the post today. Thanks again and take care.