October 23rd, 2015

Musings from Japan

Gregory Shumer, MD

Greg Shumer, MD, is a third-year resident and 2015-16 Co-Chief Resident at the University of Michigan Family Medicine Residency Program in Ann Arbor.

I spent the first two weeks of October in rural Shizuoka, Japan, rotating through clinics and hospitals in Mori-machi and Kikugawa, and observing medical education at Hamamatsu Medical School. The University of Michigan Department of Family Medicine has a unique and positive relationship with the Shizuoka Family Medicine residency program that allows for collaboration. I lived in Japan for 1 year before medical school, and I was thrilled to be accepted to the international rotation in Shizuoka. Below are some of the most striking observations from my time in rural Japan.

During an afternoon clinic session with Dr. Yamada at Mori-machi clinic, I observed a stretch when she saw patients aged 83, 77, 86, 91, and 96 — consecutively. The two patients older than 90 were both women who lived independently, and who were able to walk to clinic unassisted for their appointments.

The proportion of the Japanese population older than 65 is projected to increase from 12% to 40% between 1990 and 2050, and was estimated at 22.7% in 2009. In comparison, the U.S. elder population is projected to increase from 12% to 21% over that same time, and was estimated at 13% in 2009 (1, 2). The two major variables that are driving Japan’s rapid demographic shift are the incredibly long life expectancy (86.1 for women, 79.3 for men), and the relatively low birth rate (1.41 births per woman) (1).

Healthcare financing in Japan — Containing costs

Japan’s health financing structure is very different from the U.S. system. Japan has achieved universal health insurance through a combination of employment-based and government-financed insurance. The Japanese government keeps healthcare costs low through setting a strict national fee schedule on all services and procedures, which results in lower payments to physicians and hospitals than in the U.S. The fee schedule sets the price, and doctors are then paid fee-for-service (1). Prices for services that increase in volume over time tend to be lowered to control cost. For example, the price for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head was recently reduced by 30% to 11,400 yen (US$104) (3). Because of efforts like these, Japan spent just US$2878 per capita on healthcare in 2009 (8.5% GDP), compared with the US which spent US$7,960 per capita on healthcare in 2009 (17.4% GDP) (2).

Universal coverage in Japan improves access and eases transitions of care

One afternoon, I accompanied Dr. Tsunawaki on a home visit to see a 90-year-old woman with advanced stomach cancer, who had been discharged from the hospital 1 week prior with a plan for home healthcare services with focus on comfort care. I asked him about the process of discharging a patient with home services or to a long-term care facility. I voiced my frustration about difficulties I often encounter when trying to find placement for patients who are uninsured or underinsured in the U.S., which can delay discharge. He explained that because of the universal healthcare system in Japan, the process of discharging any patient home with home services, or to a long-term care facility, is a relatively simple and efficient process.

Brief comparisons: U.S. vs. Japanese healthcare systems

Although several aspects of the Japanese healthcare system work well, the strict national fee schedule isn’t perfect. As a result of low reimbursements, physicians must see a high volume of patients per day, squeezed into shorter visit times, which can disrupt the physician-patient relationship. Although the Japanese system provides less benefits for physicians, there is no shortage of well-qualified doctors, and it keeps costs low and access high for consumers, making it a successful system, in my opinion.

The U.S. spends the most money in the world on healthcare with variable results on quality metrics compared with other countries (2). The Affordable Care Act (ACA) helps by decreasing the number of uninsured patients through the Medicaid expansion and other measures, and by creating measures to increase access and (potentially) lower costs. However, it fails to provide universal coverage, and how the ACA will affect spending in the near future is unclear (4). Because of this, the U.S. would be wise to continue learning from healthcare systems with universal coverage that have been successfully implemented, like those in Japan and other industrialized nations.

Opioids are rarely prescribed in Japan

While I was working with Dr. Horie one morning at Morimachi clinic, we saw a 66-year-old man with chronic low back pain that had acutely worsened. Dr. Horie refilled his prescriptions for Tylenol and topical menthol-based pain-relief pads, and provided some stretching and strengthening exercises for his low back.

Outside of the patient’s room, I asked Dr. Horie about how often opioids are prescribed to patients in Japan.

“Almost never,” he told me. “Really, only for terminal patients to help with their pain.”

“What about postoperatively? Or for acute pain relief after injuries?” I questioned.

“No, we primarily use NSAIDs, Tylenol, and pain relief pads.” He explained matter-of-factly.

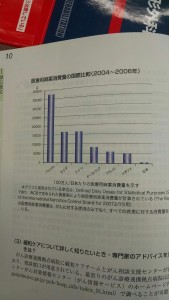

He then showed me a chart (pictured left) that visually displayed how the U.S. and Japan are on opposite ends of the spectrum in terms of opioid prescribing habits: The U.S. prescription rate is represented by the bar on the far left of the graph, and Japan’s rate is the barely visible bar on the far right. In comparison to Japan’s strikingly low use of opioids, the epidemic of opioid drug abuse and misuse in the U.S. is well-documented: An estimated 259 million prescriptions were written for opioids in 2012 — enough for every American adult to have a bottle — and every day an estimated 46 people die from prescription medication overdoses (6).

I saw several patients with complaints of acute and chronic pain while working in clinics and hospitals in Japan, but the only time I saw opioids used was for terminally-ill patients with cancer-related pain during home visits.

Finally, Japan is beautiful

If you are searching for a spot to spend your next vacation or work-related adventure, I highly recommend the rolling green hills of the Japanese countryside. The natural beauty of the countryside is matched by the warmth and hospitality of the people. Thank you to everyone at Shizuoka Family Medicine for making me feel at home during my 2 weeks there; I hope to see you again soon.

Special thanks to Dr. Machiko Inoue, the program director at Shizuoka Family Medicine, for helping to coordinate my experience in Shizuoka, and also to Professor Jersey Liang, for the education he has provided through his Health Systems course at the University of Michigan Executive Master’s Program in Health Management and Policy, which helped provide some of the material for this post.

References:

1. Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K. Understanding Health Policy, Chapter 14. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2009.

2. Squires, David A. Explaining High Health Care Spending in the United States: An International Comparison of Supply, Utilization, Prices, and Quality. Issues in International Health Policy. The Commonwealth Fund. 2012; 1.

3. Ikegami N, Campbell J. Japan’s Health Care System: Containing Costs And Attempting Reform. Health Affairs. 2004; 23:26.

4. Connors E. Health Care Reform—A Historic Moment in US Social Policy. JAMA. 2010; 303:2521.

5. Cancer Palliative Care Guidebook. Nihon Ishikai. 2013. pg 10.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Vital Signs – Opioid Painkiller Prescribing. 2014. (http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/opioid-prescribing/)

Excellent analysis. Lots of positives which US healthcare can take from Japan.

Excellent report! Here in Brazil we have a universal coverage system, but unfortunately we spend just 500 dolars per capita.

Thank you for this excellent article. I am currently a medical student in a US program training in a department of diagnostic radiology in central Tokyo.