August 7th, 2015

Cat Herding

Gregory Shumer, MD

Greg Shumer, MD, is a third-year resident and 2015-16 Co-Chief Resident at the University of Michigan Family Medicine Residency Program in Ann Arbor.

“The day you earned your MD, you became a leader… A leader to your future patients, a leader in your community, and a leader within the healthcare system.”It’s May 7th, 2015 – day 1 of the annual Chief Resident Leadership Development Program in Kansas City, Missouri. It’s an event meant to welcome the newly selected chiefs from family medicine programs around the nation and instill them with leadership skills and enthusiasm as they enter their third year of residency and chief years at their programs. The program’s director is delivering an introduction speech to his audience – roughly 150 bright-eyed chief residents, including myself and my co-chief, who traveled from across the country to be part of the 3-day conference.

“And as chief resident, you are a leader of leaders – not an easy task!” he continues. “Leaders are often independent and opinionated, and trying to direct an entire group of them is as easy as trying to herd a group of cats.”

“And as chief resident, you are a leader of leaders – not an easy task!” he continues. “Leaders are often independent and opinionated, and trying to direct an entire group of them is as easy as trying to herd a group of cats.”

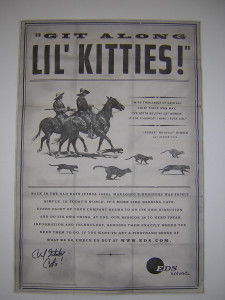

He pushes a button on his handheld pointer, and a video begins on the big screen projector, showing images of rough-and-tough cowboys trying to circle up and direct large groups of small cats.

“Anyone can herd cattle,” one of the cowboys says as cats meow in the background, “but holding together 10,000 half-wild shorthairs, now that’s another thing altogether.”

We had a good laugh, and the chief conference was under way.

During our 3 days together, we learned that we all share common challenges. Scheduling conflicts are near the top of the list. Low morale and burnout are other common themes — attributed to long hours and the natural stress that occurs during residency. We also realized that family medicine programs across the country share several positive themes, such as the sense of community and teamwork that exists within programs, and the strong bonds that develop through working together at the hospital and in clinic.

We learned that as chief residents, we wear many different hats. In an average week, we serve as leaders, organizers, motivators, negotiators, problem solvers, teachers, and of course, third-year resident physicians in clinics and at the hospitals. Through Myers-Briggs personality testing, we discovered our different leadership styles. As an ENFP (Extroverted, iNtuitive, Feeling, Perceiving), I fall in the category of “idealist,” with strengths that include diplomatic persuasion and cultivating morale, and weaknesses that include an aversion to conflict and difficulty with setting limits for bad behavior. We learned about five leadership practices: model the way, inspire a shared vision, challenge the process, enable others to act, and encourage the heart.

By the end of the conference, I felt inspired and ready to take on this whole chief resident thing. I had been performing chiefly duties for about a month — dealing with scheduling conflicts, leading the annual residency retreat, participating in monthly meetings, etc — and it was the perfect time for this type of motivating and thought-provoking experience. Now, close to 3 months later, I think back to my time in Kansas City whenever I start to feel tired or overwhelmed.

July 1st has come and gone. The new interns arrived with their nervous smiles and freshly ironed white coats, and we all moved up a rung on the ladder. As a chief resident, the beginning of a new academic year brings new challenges. But it also allows for new and exciting opportunities — chances to serve as a resident advocate, to “model the way” for the interns and second-years, and to inspire positive change, little-by-little, day-by-day. Thankfully, my co-residents and faculty here in Ann Arbor make it rewarding and fun.

So, onward and upward. Cat herding — ain’t a feeling like it in the world!

41 years ago I became the Chief Resident in Medicine in the 3rd largest teaching hospital in Canada.. I had no co-chief. It was not a job I wanted but it was a job that needed to be done. I learned three things about being a “chief”:

1. Listen to the problems of the trainees.

2. Listen to and investigate the complaints of all the other people in the institution about the trainees. Don’t prejudge. Collect the evidence. Find a middle ground.

3. When somebody can’t be found to willingly step forward to do a job (cover the shift et cetera), do the job yourself. It’s easier.