April 7th, 2011

The Colors of Life

Greg Bratton, MD

For a week, the patient in bed 301 had been fighting.

After being found unresponsive and hypothermic in the field, this 48-year-old male was brought to the ICU and was treated for metabolic acidosis, end-stage liver disease, hepatic encephalopathy, and an acute upper GI bleed, all in the context of presumed alcohol intoxication/withdrawal. It was not until later that we discovered that, in conjunction with everything else, he had ingested a substantial amount of ethylene glycol, better known as antifreeze.

From what we could gather, he was a transient and had spent the last several years living in the streets and his family members’ couches. In fact, 3 months ago, he left his aunt’s house one morning and “disappeared,” not to be heard from or seen again. It wasn’t until we called the number in his chart to obtain collateral information that his family discovered his whereabouts.

He had a past medical history significant for hepatitis B andC but continued to abuse alcohol and other substances. As a result, his liver had been so severely damaged that he suffered from esophageal varices, recurrent ascites, and altered mentation. Now, as a result of his antifreeze ingestion, he had grade D esophagitis as well; hence his GI bleed.

While in the ICU, he was on a ventilator for respiratory failure, hemodialysis for acute kidney failure secondary to the ethylene glycol intoxication, pressors for hemodynamic instability, and serial paracenteses. And despite our best efforts, he simply did not improve. He failed multiple weaning trails from the ventilator and could not maintain his blood pressure without medication. We all knew early on that his prognosis was poor.

One night, while I was on call, I stopped by his room to see how he was doing. With the beep of an empty IV bag in the background and the timed inspirations and expirations of the ventilator blowing precisely every few seconds, I stood beside his bed and quickly realized that his prognosis had gone from “poor” to “fatal.” Sometime during the last hour or so, he had begun to bleed out of everywhere. His foley, rectal tube, endotracheal tube, and nasogastric tube were all full of blood; his central and peripheral lines had saturated their dressings. His body had gone into DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, a poor prognostic sign which carries with it 10%-50% mortality. Casually, DIC stands for “Death Is Coming.”

I quickly contacted family and advised them to come as soon as possible. For his mom, it meant driving 3 hours from Oklahoma. I assured her that I would do everything I could to keep him alive until she arrived, but I could make no promises. She said, “Please, do your best.” So we began to hang blood and clotting factors to try to limit his body’s destruction. The family arrived to bedside around midnight.

It was about 3 o’clock in the morning when I got the page from my nurse. After what had to be a very painful and difficult couple of hours, his family had decided to withdraw care. Out of respect for the family, I wanted to be present to answer any last questions and to show my support for their decision.

We extubated him, turned off the pressors, gave him some pain medication, and made him comfortable. Then, I left the room to allow his family to share in the moment privately, but sat outside within view of the patient, just in case.

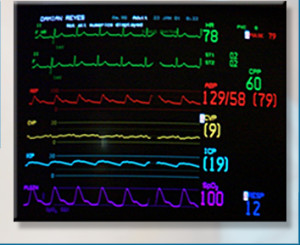

As I sat and waited for nature to run its course, I found myself staring at the monitor. This 20” black screen with a black background captivated me like nothing has before. I watched the red cardiac rhythm line, anticipating its demise to asystole. I watched the blue respiration line, waiting for it to cease making upward movements as his breathing failed. And I watched the green pulse line and rate number continue to fall toward zero. I was enamored with the little black box and all the information it was feeding me.

As I sat and waited for nature to run its course, I found myself staring at the monitor. This 20” black screen with a black background captivated me like nothing has before. I watched the red cardiac rhythm line, anticipating its demise to asystole. I watched the blue respiration line, waiting for it to cease making upward movements as his breathing failed. And I watched the green pulse line and rate number continue to fall toward zero. I was enamored with the little black box and all the information it was feeding me.

But then, out of the corner of my eye, I saw my patient’s mother, aunt, and brother, leaning over his bed, whispering caring remarks into his ear, holding his hand, and crying. They were doing everything they could to demonstrate to him their love and heartbreak. They ran their fingers through his hair, caressed his legs, and kissed his cheeks. It was a terrible, beautiful sight.

Suddenly, I realized that I had fallen victim to what happens to so many doctors. I stopped feeling. I stopped seeing Bed 301 as a person. To me, he was a critically ill patient that needed to have care withdrawn because Medicine told me he would not survive. I had accepted that he needed to die because his condition was deteriorating rapidly. What else could we, as doctors, do? Dump tons of blood and blood products into him, at the cost of depleting the blood bank and his family’s bank account and delaying the inevitable??

I forgot that he was someone’s son, someone’s brother, someone’s love. I forgot that even though Medicine told me he would not survive, it meant nothing to his family who relied on faith and miracles. I discounted that all his family wanted was a chance for him to survive. And I thought of my own son and family and, abruptly, the power and emotion of the moment became real to me.

I was affected that night.

I am nearing the end of my residency and, perhaps, have become jaded and skeptical and insensitive to many situations. I find myself doubting a patient’s pain level due to presumed drug-seeking; questioning the truth behind a patient’s story; and not giving a patient the benefit of the doubt when a treatment regimen fails.

What Bed 301’s passing did for me was reinforce to me that patients are not objects. Their conditions are not black and white. In fact, they are people, dynamic and colorful, just like the rainbow of colors bouncing on the monitor.

And, although I was focused on the right thing the night the patient in Bed 301 died, my context was way wrong. Those colored lines in the little black box represented life, not vital signs.

So, thank you, Bed 301, for reintroducing me to the colors of life. When I stop and look at them, they are beautiful.

I’m currently a sophomore at a liberal arts school for undergrad. in anthropology and music, and recently became fascinated with medicine and healthcare. I’m doing some shadowing this summer and have corresponded with some current medical students and doctors (internists, OBGYNs, etc.). I was just bumming around and found this blog, and reading this story really encouraged me. I’m sure I can’t possibly comprehend the amount of work and time that go into becoming a doctor at this point, but what inspires me to become a doctor is helping people. When it comes down to it, you’re working with a person, a somebody with a life. Though I’m clearly not qualified enough to have real authority on this, it seems that treating a person (even if they do not recover) depends on more than purely the biomedical, the quantitative. I hope that if I do end up in medicine I don’t lose sight of the person as a whole (not just body parts and symptoms and what have you) that I’m working with. Thank you for posting this!

Those who are born shall die but we cannotclose our feelings and build a barrier to feel helpless.

Absolutely beautiful column. Thank you. I hope the lesson of that night stays with you–and others–throughout their careers.

A very moving column which I thank you for sharing. It is not just doctors who need reminding that a pulse, even weak, a breath, even labored, represents life.

So much is meaningfully reflected in these lines -the colored ones on the screen as well as those Dr. Bratton has written.

I hope that at some point he might express thoughts about the social and the economic aspects of a case such as this.

I was deeply touched by your moving column, and made me appreciate once again the value of each & every person. I served my people as a government Doctor in the boonies in the Philippines (in the ’70’s). Some places I visited couldn’t be reached by a 4-wheel drive vehicle, & I often had to walk, ride in canoes with outriggers to get to a patient. I delivered 350 babies in 6 years in homes (sometimes just one-room serving as bedroom, living, dining room & kitchen), & attended to health needs (lots of TB, some tetanus, malaria, leprosy & other infectious disease problems). I loved my people & treated each one as a real person, & to me, they were the most beautiful human beings on earth, even if they lived hand-to-mouth & were dirt poor. Your article reminded me of those very difficult but satisfying years (no labs, no x-rays, just using the “clinical eye”), where each patient lost was a personal loss. Thank you!

What a beautiful reminder to all of us in the health care professions that, as proclaimed so eloquently by President Wagner of Emory University, we must remember that we are treating people, not diseases.

Dr. Bratton just wrapped up the entire conundrum of life’s final chapter in one blog post. What to do, and for how long, in the face of ominous prognostic signs, multiple chronic illness, and caring family who have been put through the wringer not only by the patient’s illness, but by the patient himself. Questions that have no good answers except for the ones each patient, each family, and each clinician must find for themselves in the moment. I invite Dr. Bratton (and his readers!) to join us on our website, http://www.closure.org, and enter our discussion on end-of-life. Well done.

Great article with thoughtful words that come from the heart. Thanks for sharing. We all need a reminder that we are not just treating patients but real people…

Beautifully described feelings and emotions of a human being inside a “doctor”. In fact, this is what drew me into critical care. The end of life care issues are very delicate and require a balance between a medicine expert’s opinion and control of feelings as human being. Not everyone can be good at it. As the current population ages, we will see more of this and will have to deal with, of course in a human way. Great job.

I think you know quite well that this person is going to die. The ethylene glycol on top of the damaged liver from alcohol produced a double whammy. That antifreeze is going to damage that kidney soon if he were to survive that DIC.

I think it’s next to impossible to tell the patient and the family that the use of these resources is futile. Society is poised also to pound you with a lawsuit once the suggestion of denial of medication is apparent. This forces you to go through the motion of giving transfusions, IV fluids, oxygen, etc when the outcome actually is to prolong suffering. You can’t reveal your honest feeling because to do so will harm your name, reputation, and medical license. I wish non-medical people realize that a lot of disease can’t be cured.

Thank you for this article.

“Those colored lines in the little black box represented life, not vital signs” – so true, but so often we forget about it ! Great article – so many nights on call I found myself in the same situation on ICU

Thank you for this moving tribute to life.

You mention in passing the huge medical bill. It seems to me the liquor industry, which profits from this destruction of lives, should be pay the cost of the carnage they create. A tax on hard liquor, put into a fund to pay medical bills deemed to be alcohol related, and increased if the tax proves inadequate, seems only fair.

There is no way to compensate the family for its heartbreak, captured in the moment that you describe in the ICU but no doubt extended over many years of pain. But surely there should be some financial pushback against an industry that profits at the expense of precious health care dollars and precious lives.

I currently work in the clinical setting and often get angry at some of the insensitivities and pre-judgements I see. Your piece is a wonderful reminder that as clinicians we only know the person by what we have read or heard and have not lived life in their shoes. I know from my life, that I am grateful for those who cared and intervened instead of passing judgement allowing me to come full circle. I try never to forget where I came from and attempt on a daily basis to remain humble. I will always remember your caring words and wonderful perspective on the colors of life of the monitor. Stay well and happy and bless you on your continued journey.

Thank you! This is the kind of realization we as patients hope to see in our providers. I admit I have been to the point in my illness and recover of not seeing providers as caring in any way. This article has done a lot in restoring my faith in medical providers and honestly, humanity in general. Thank you.