June 29th, 2016

The Specialty Shuffle

Harrison Reed, PA-C

More recently, a well-meaning acquaintance told me that the PA profession was important because “most of you work in primary care, right?” While I felt the comment required some factual correction, I found my own response somewhat lacking. The actual percentage of PAs in primary care is somewhere between 20 and 30%, I told him. But I couldn’t answer the next question: why?

I could just point to physicians. After all, we do “pretty much” what they do, right? It makes sense that our specialty distribution should mirror theirs and the same factors pulling physicians away from family practice should affect PAs as well.

But it’s not that simple.

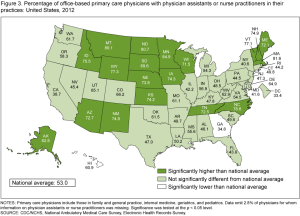

New research by Perri Morgan and colleagues published in the Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants (JAAPA) sheds light on the interplay of physician-PA specialty selection. To start, the study confirms that the proportion of PAs entering primary care is declining, from 50% in 1997 to 30% in 2013. It’s a finding that mirrors trends in other healthcare professions and by itself is not surprising.

But the authors found another correlation in their data: the positive link between PA employment and the ratio of MD-to-PA salary. If that one made you pause, it should. Of course PAs might be attracted to specialties in which we make higher salaries. But why would there be more PAs in specialties in which our physician colleagues collect bigger paychecks relative to PAs?

Perhaps the answer lies not in the supply of PAs (i.e., where we choose to practice) but in the demand for them (i.e., the number of jobs available). High-earning physicians stand to make more money when they free up time by offloading clinical tasks to PAs (like a surgeon who operates more by hiring a PA to provide post-operative care). PAs in these fields also represent a better bargain when compared to hiring another highly paid physician in the same specialty.

It might sound intuitive and straightforward, but the economics of specialty distribution are essential to understanding why a smaller proportion of PAs are entering primary care. If there really is a primary care provider shortage, one that is set to worsen in the coming decades, we should consider insights from research like the Morgan study before planning interventions.

If PA salaries rise at rates greater than those of our primary care physician colleagues, practices will reap fewer financial rewards by hiring PAs. If well-meaning incentives designed to lure PAs to underserved primary care clinics (like salary increases, bonuses, or loan repayment) drive up the average cost of a PA in primary care beyond what non-subsidized practices can afford, we may see a further decline in the overall percentage of PAs in primary care.

Of course, we have always needed a healthy supply of primary care providers and the percentage of clinicians in that field must grow as we insure more Americans and as our population ages. But the choppy seas of healthcare economics respond to legislative and financial interventions in unpredictable ways. More healthcare workforce research might help us see the waves before they come crashing down.

; [/php]/images/AU000_hreed.jpg)

As long as reimbursement favors physicians who perform procedures, you will see more PAs and NPs, in subspecialties where our abilities can extend our employers’ ability to do more procedures while we cover the important, but less lucrative, ancillary care. This will penalize both the primary care and mental health fields which require more nuanced and personal care of the whole patient at a time when needs are greater than ever.

It’s true that the PA model can enable some specialists to shift a higher proportion of their time to a lucrative niche. However, a PA allowed to practice at the full scope of his/her license still represents a financial advantage over an MD in Primary Care and Mental Health. Legal/regulatory barriers to PA practice and PA reimbursement will nullify some of this advantage, however. That is why professional advocacy can directly benefit patients and access to care. -HR

As a Primary Care Doctor who hired a NP, I can say many of my long-term patients aren’t willing to see the NP unless it is a simple UTI or sinusitis. When an internist in my practice retired, I was unable to find another internist to share office expenses, so I hired a NP. Since they get paid a flat salary (and don’t suffer the income loss on ice days vacation days, or slow days the way I do) they don’t share the burden of paying half the rent, medical and office supplies, and salaries. If she has a couple hours without a patient, I can’t help but think, “There’s $100 down the drain.” She is helpful with completing odious forms for Blue Cross Advantage etc. Hopefully her practice will continue to build, but I’ve been surprised how many primary care patients insist, “I only want a doctor to see me.” Very frustrating when my schedule is overbooked and hers underbooked! I wish there were more residents going into primary care for me to recruit!

While problems like the ones you discuss exist, I believe they represent a shrinking problem as the public and medical industry both become better educated on the role and abilities of PAs and NPs. Advocacy and confidence from MDs/DOs does wonders for patient confidence in PAs and NPs. Perhaps as a business owner you can look for resources that may enable you to better collaborate with and promote your employee. This is a popular issue among many PA/NP authors and consultants and there are a lot of great ideas out there. Good luck!

As a 60 y.o. Family Physician, I know the tale of declining reimbursement in my chosen specialty well. I train PA students yearly. So far, only one has chosen my specialty as his area of practice. We need more PAs to do so. Many studies have shown that medical students will not fill the gap in Family Medicine as those of us over 50 reach retirement age. Who will provide care as the “frontline” of Medicine if not PAs and NPs?

As a PCP (FM-Geriatrics) I can say the unique administrative burden, and the expansion of knowledge to remain current in primary care combined with the lack of proper reimbursement, is likely why even PAs choose to avoid this needed specialty.