November 17th, 2010

Anacetrapib: “Knock-Your-Socks-Off Effect on HDL and a Jaw-Dropping Effect on LDL”

Larry Husten, PHD

Following the failure of torcetrapib in 2006, the future of cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitors appeared quite troubled. Now, with the results of DEFINE (Determining the Efficacy and Tolerability of CETP Inhibition with Anacetrapib), presented at the AHA in Chicago and published online in the New England Journal of Medicine, the future for this novel class of drugs appears much brighter, but the final decision about anacetrapib will have to wait for a larger clinical trial.

DEFINE was designed to assess the side-effect and overall safety profile of anacetrapib, as well as its effects on lipids. The trial randomized 1623 patients already taking statins or other lipid-lowering agents to either anacetrapib or placebo for 18 months.

The primary endpoints of the study were the percent change in LDL at 24 weeks and the side-effect profile at 76 weeks. Compared to its effect on placebo, anacetrapib reduced LDL by 40% and raised HDL by 138%:

LDL at baseline and 24 weeks:

- Anacetrapib: 81 mg/dL and 45 mg/dL

- Placebo: 82 mg/dL and 77 mg/dL

HDL at baseline and 24 weeks:

- Anacetrapib: 41 mg/dL and 101 mg/dL

- Placebo: 40 mg/dL and 46 mg/dL

There were no differences between the groups in blood pressure, electrolytes, or aldosterone levels associated with anacetrapib.

There were 16 (2%) adjudicated cardiovascular events in the anacetrapib group versus 21 (2.6%) events in the placebo group. There were 8 revascularizations with anacetrapib versus 28 with placebo.

“Anacetrapib has a knock-your-socks-off effect on HDL and a jaw-dropping effect on LDL,” said Chris Cannon, the study’s first author, in an AHA press release.

November 16th, 2010

“Phone It In” Heart-Failure Monitoring Offers No Advantage Over Usual Care

Larry Husten, PHD

CardioExchange welcomes Sarwat I. Chaudhry, first author of an NHLBI-funded trial in which 1653 recently hospitalized heart-failure patients were randomized to telemonitoring or usual care. The findings, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, failed to show an advantage of telemonitoring in the primary endpoint: rehospitalization for any reason or death from any cause within 180 days after enrollment (52.3% for telemonitored patients, 51.5% for usual-care patients).

Telemonitoring was conducted via a telephone-based voice-response system. Every day, patients in the telemonitoring group phoned in information about their symptoms and weight, which was reviewed on weekdays by site coordinators. Predetermined, clinically relevant “variances” in patients’ responses flagged clinicians’ attention. Here, Chaudhry answers questions about the trial, posed by CardioExchange editor Anju Nohria, MD.

Q: You report that adherence to the telemonitoring system deteriorated over time: Only 55% of patients were still using it at least 3 times per week by the end of the trial. Physicians’ rate of adherence (attention) to the flagged “variances” is not reported — can you share that information with us? Also, how often did the physicians actually change therapy in response to a variance, and how often did they simply document a noted variance and choose not to intervene?

A: Our protocol required clinicians to check the telemonitoring information every business day and to document their responses to variances. The study Coordinating Center examined this documentation every 2 to 3 weeks to ensure that the variances were being reviewed. Therefore, we can say with confidence that the information was being carefully considered in a timely manner. Although physicians were required to document their management of variances, they didn’t record the information systematically. We do know that the cardiologists responsible for clinical management of patients’ heart failure made purposeful decisions about medication adjustments, education about dietary indiscretions, referrals for office visits, and so on.

Q: Do you think the findings might have been different if the telemonitoring system had required patients to call in weekly rather than daily? For example, might a once-a-week protocol have improved both patient and physician adherence, and also allowed patients a chance to perceive changes in how they felt, such that their responses would trigger a variance?

A: It is difficult to know whether less frequent monitoring would have produced a different result. Part of the goal of a daily monitoring intervention is that it becomes part of a patient’s daily habit. In fact, patients were instructed to phone into the telemonitoring system shortly after measuring their body weight in the morning, so that the call would become routine. Also, the opportunity to detect early changes in health may be lost with a less frequent intervention.

Q: The article does not describe the “usual care.” Did it typically involve a nurse-based heart-failure management program, or individual physicians who responded to patient calls as needed?

A: Similar to national practice patterns, “usual care” did not typically include nurse-based heart-failure management programs. Our sites were general cardiology practices, and such resources are not widely available. As in standard clinical settings, patients in usual care contacted physicians when they felt they needed to do that. There were no proactive contacts by clinicians.

Q: Does your study allow you to draw any broader conclusions about clinical management?

A: It’s important to keep in mind that our study was a rigorous examination of one approach to telemonitoring. It should not be misapplied to telemonitoring or disease management in general. Other components — such as patient education, medication support, or interventions aimed at patients’ caregivers — may ultimately prove to be more effective. Such strategies for supporting patients and physicians must be carefully tested before they are adopted widely.

CardioExchange readers, what conclusions do you draw from the telemonitoring in heart failure trial and its negative findings?

Editorial Note: CardioExchange editor Dr. Harlan Kumholz was the senior investigator on this trial.

November 16th, 2010

Is There a Statistician in the Room?

Susan Cheng, MD

Several Cardiology Fellows who are attending this week’s AHA meeting are blogging together on CardioExchange. The Fellows include Susan Cheng, Madhavi Reddy, John Ryan, and Amit Shah. Check back often to learn about the biggest buzz in Chicago this week — whether it’s a poster, a presentation, or the word in the hallways. You can read the preceding post

While I was sitting in on an AHA epidemiology session focused on ideal cardiovascular health status, based on what’s now called Life’s Simple 7, somebody mentioned using “principal components analysis.” This method was used to re-categorize a measure of healthy diet — basically because the vast majority of people (Americans) in the study would otherwise be categorized as eating unhealthily, which would render the diet measure useless. As somebody with a bit of formal training in biostatistics, I was familiar with most of the methods mentioned in the session. So I kind of know what principal components analysis is meant to do but only in a very general sense, and I would definitely need a statistician to help me understand how it was applied in this particular study. I wondered how many other people in the room might also have felt stumped by this part of the methodology.

Having heard a lot of buzz about ROCKET-AF, I later ventured to drop by the plenary session where this trial was being presented. The post-presentation discussion was extremely interesting, but again involved statistical concepts that I didn’t feel completely familiar with, as somebody who isn’t active in clinical trials research. Following Ken Mahaffey’s very polished presentation of the results, Elaine Hylek presented her discussant opinion and focused on the potential pitfalls of non-inferiority trial design. By the time she was done, I was wishing that I could watch the trial presentation again so that I could better scrutinize the methods. Only after brushing up on the differences between non-inferiority and superiority trials (this site is helpful), did I feel that I could revisit the slides online to try to figure out the methodological nuances for myself.

So, I’m wondering if maybe there’s something missing at conferences like AHA. Cutting-edge research often involves not just ongoing advances in cardiovascular science but also ongoing developments in the statistical methods being used — including risk prediction models (C-statistics, net reclassification index, etc.), genome-wide association analyses, non-inferiority trials, and adaptive trial designs. Could there be a way to help the average conference attendee make better sense of methods in order to better make sense of the results? If conferences like AHA are to serve as a form of CME, perhaps they should have a greater emphasis on keeping us all up-to-date on how to critically appraise the latest research. Perhaps more statistics primers scheduled at the beginning of the conference, or each day of the conference, would help? Or journal-club-like sessions at the end of each conference day? Or maybe just an online resource that reviews some general concepts and some more advanced ones in a relatively accessible format?

Then again, I could be the only person at AHA hungering for more stats knowledge while wandering through the convention halls. If so, just let me know…

November 16th, 2010

Putting the EMPHASIS on Eplerenone for HF

Paul Armstrong, MD

In the EMPHASIS-HF study, aldosterone inhibition with eplerenone reduced the rate of death from cardiovascular causes or heart-failure (HF) hospitalizations by about 37% (compared with placebo) in patients with functional NHYA class II HF. CardioExchange welcomes Paul Armstrong, Professor of Medicine in the Division of Cardiology at the University of Alberta, to answer our questions about this study. His editorial on the EMPHASIS-HF study appears in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The Data Safety and Monitoring Committee terminated the study early. How would you respond to those that point out that this often exaggerates the treatment effects?

The results of EMPHASIS-HF are so clearly positive and consistent with prior work that I suspect this was a minimal issue in the decision to end the study early.

Few patients (about 20%) in EMPHASIS-HF were treated with an implantable cardiodefibrillator (ICD) or cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT). Would you expect such therapy to blunt the benefits of eplerenone? Should we restrict aldosterone inhibitor therapy to patients without ICD or CRT therapy?

Device implantation might have blunted some of the effect, but by no means all in my view. A future study might usefully explore whether device therapy can improve outcomes on top of eplerenone.

Although the trial purportedly studied patients with “mild” (NHYA class II) HF, they appeared to have advanced disease (mean LVEF, 26%). Should patients with moderately reduced EF (30-50%) be treated with an aldosterone inhibitor?

We will need to see from additional analysis the extent to which baseline EF interacted with treatment effect, but I would guess that anyone with a depressed EF would benefit from this therapy. I recall that the EPHESUS trial showed a benefit for post-MI HF patients with an EF mean of 33%. The diastolic dysfunction among patients with normal EFs are the subject of ongoing studies.

Following the RALES trial, widespread use of spironolactone in HF patients resulted in an increased incidence of hyperkalemia and cardiac-related death. Should we expect the same with eplerenone?

It has recently been shown that careful monitoring of renal function and electrolytes is warranted and this results in safer general use. I believe the Ontario data published in NEJM may have overstated the safety issue.

In the editorial that accompanied the study, you recommended that spironolactone be used in HF patients and the more expensive eplerenone be reserved for the rare patient who has disabling side effects from spironolactone. Are there any differences in efficacy or safety between the two?

The principal side effect of aldosterone is painful gynecomastia, which occurs in about 10% of men and can be avoided with eplerenone. There is not a direct head-to-head comparison of these antagonists: However, based on what literature is available, I believe they are otherwise very similar regarding their safety and efficacy.

November 16th, 2010

What Does BASKET PROVE Have to Prove?

L. David Hillis, MD and Richard A. Lange, MD, MBA

What to make of new findings that DES are just as good as BMS for treating lesions in large coronary arteries? David Hillis and Rick Lange provide a brief tour of the relevant issues.

Getting a handle on the study…

Previous data suggested that the use of DES in large native coronary arteries confers no benefit and may, in fact, cause late harm due to stent thrombosis.

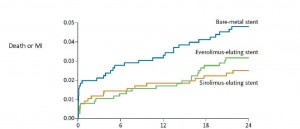

In BASKET PROVE (BAsel Stent Kosten Effektivitäts Trial – PROspective Validation Examination), 2314 patients needing stents that were 3 to 4 mm in diameter were randomly assigned to receive (a) a first-generation sirolimus-eluting stent (Cypher Select, Cordis), (b) a second-generation everolimus-eluting stent (Xience V, Abbot Vascular), or (c) a bare-metal (Visions, Abbott Vascular) stent. All patients were treated with aspirin and clopidogrel for 1 year.

At 2 years, the rate of nonfatal MI or cardiac death did not differ significantly among the three groups. However, the rate of target-vessel revascularization was significantly lower in patients who received either DES than in those who received a BMS.

| Cardiac Death or MI | TVR | |

| BMS | 4.8% | 8.9%* |

| Sirolimus DES | 2.6% | 3.7% |

| Everolimus DES | 3.2% | 3.1% |

* p < 0.007 comparing BMS to either DES)

During the first 6 months after stenting, a statistically nonsignificant trend toward a lower rate of cardiac death and MI was seen with both DES, compared with BMS. However, since the clinical event rate was lower than expected, the trial was underpowered to detect small differences.

Is my patient a” basket case”?

One nice thing about BASKET PROVE findings is that they apply to a “real-world,” rather than a highly selected, patient population. One third of the patients had stable angina, one third had acute coronary syndromes, and one third had acute STEMI. No limit to the number of coronary arteries treated or stents used was imposed, and 76% of stents were implanted in subjects with “off-label” indications (e.g., more than one lesion per vessel, lesions in two or more vessels, lesions that were >27 mm in length, bifurcation lesions, chronic total occlusions, or acute coronary syndromes).

How do I weave these findings into my practice?

You can feel comfortable in the knowledge that there’s no harm in using DES rather than BMS in large coronary arteries (keeping in mind that the results of this study only apply to vessels 3 to 4 mm in diameter, not to smaller or larger arteries).

Should I be implanting DES, rather than BMS, in all large coronary arteries?

It’s not a slam dunk. For patients who cannot (or will not) take dual antiplatelet therapy for a year, BMS should be used. In the remainder, although it’s not harmful to use DES rather than BMS, it may not be cost effective. We need an analysis to examine whether the modest reduction in TVR (absolute reduction of 6 to 7%) justifies the increase in cost of DES over BMS.

Readers: What kind of stents do you generally recommend for large-artery stenoses, and will these findings cause you to reconsider your practice?

November 16th, 2010

GRAVITAS: No Benefit for Clopidogrel Dosing Based on Platelet Function Test

Larry Husten, PHD

The GRAVITAS (Gauging Responsiveness With A VerifyNow Assay ─ Impact on Thrombosis and Safety) trial enrolled 2214 patients with high residual platelet reactivity, as assessed by the VerifyNow P2Y12 Test measured 12 to 24 hours after the procedure. (The manufacturer of the test, Accumetrics, sponsored the trial.) Patients in the trial were randomized to either high-dose clopidogrel (additional loading dose, 150 mg daily thereafter) or standard-dose clopidogrel (no additional loading dose, 75 mg daily thereafter).

The primary endpoint ─ a composite of CV death, MI, or stent thrombosis at 6 months ─ occurred in 2.3% of patients in each group. Bleeding complications also occurred at similar rates in the groups.

“The high dose of clopidogrel doesn’t appear to improve outcomes, so alternative treatment strategies should be tested,” said Matthew Price, the lead investigator, in an AHA press release. “Many physicians have been using a high dose of clopidogrel as a default strategy in patients who are nonresponsive to the drug. We show that this strategy is probably ineffective.”

CardioExchange’s Rick Lange and David Hillis weigh in on the findings:

The GRAVITAS study shows that high-dose clopidogrel doesn’t improve outcomes in patients with high residual platelet activity. An alternative interpretation is that assessment of platelet reactivity doesn’t effectively identify individuals at high risk for a cardiovascular event following PCI.

Of all patients considered for enrollment, more than 40% had high “on-treatment platelet reactivity” (i.e., level of platelet reactivity during clopidogrel therapy), according to the VerifyNow P2Y12 Test ─ yet only 2.3% of them had a cardiovascular event in the 6 months following PCI. In essence, the positive predictive value of the test is low. Although the investigators call for testing “alternative treatment strategies” in patients with high platelet reactivity, it may be more worthwhile first to develop tests that are better at identifying individuals at high risk of having a cardiovascular event after PCI despite routine therapy. The notion that alteration of therapy based on platelet function measurements improves outcomes is still unproven.

Would you alter antiplatelet therapy based on currently available platelet reactivity studies? If so, how?

November 16th, 2010

First-Time Presenter

John Ryan, MD

Several Cardiology Fellows who are attending this week’s AHA meeting are blogging together on CardioExchange. The Fellows include Susan Cheng, Madhavi Reddy, John Ryan, and Amit Shah. Check back often to learn about the biggest buzz in Chicago this week — whether it’s a poster, a presentation, or the word in the hallways. You can read the preceding post

Yesterday was my first time presenting at AHA.

I arrived early in the morning to upload my slides, as we had been instructed by the IT staff to have our talks on the system three hours before our scheduled session. And after Susan had described the technical difficulties of the day before, I did not want to have a similar experience.

Later in the morning, my mentor Kim Williams called me to practice our presentation. As we started to rehearse, we realized that we could add some more statistics into the presentation. This process consumed us right up to the start of our session “What’s new in nuclear cardiology.” So despite my previous organization, I had to jump to the top of the queue at the speakers’ resource center and ask the staff to re-load my talk.

I then left the lofty heights of Hall A and walked to the smaller rooms closer to Lake Michigan. This was the first formal scientific conference at which I have presented data. Over the last few days I have been struck by the solemn, serious tone of the presentations. Unlike CCU conferences that we present at during fellowship, these were taciturn discussions of science with no room for jokes or inaccuracies. To say that I was nervous would be an understatement. I am not normally anxious about talks, but this was so different from what I was used to.

I was scheduled to talk after the intermission in the afternoon. However, when the last speaker scheduled for before the break was late, I was asked to substitute. I guess I should have said no. One would think that it would not matter, because at this stage, I knew our data very well and had been freshly working on stats, and so I agreed to present before the intermission. But it did shake me unnecessarily, which was foolish. In hindsight, I did not have sufficient mental preparation and flew through my slides in what felt like a whirlwind. Halfway through, I realized this, and I managed to pace myself and get across more of our finer points . Still, the question session was a struggle, with fair but tough questions, which I was unprepared for.

As I was leaving the room at the start of intermission, I saw a half dozen fellow friends of mine coming down the hall to attend my talk. A senior faculty member from Boston also was coming to hear me speak. It was quite touching to see so many of them prepared to make the long walk to the Eastern conference room to show support and solidarity. And although I had initially felt defeated because I did not do as good a job as I would have liked, seeing the support that my colleagues were willing to offer me was heart-warming and inspiring. Next time, though, I will insist on sticking with the time initially assigned for me.

What have others experienced while presenting at AHA? Do people remember the first time they presented? Any advice to those who are still about to give a talk?

November 15th, 2010

AHA Science and Technology Hall

John Ryan, MD

Several Cardiology Fellows who are attending this week’s AHA meeting are blogging together on CardioExchange. The Fellows include Susan Cheng, Madhavi Reddy, John Ryan, and Amit Shah. Check back often to learn about the biggest buzz in Chicago this week — whether it’s a poster, a presentation, or the word in the hallways. You can read the preceding post here.

How do you get the most out of the always-interesting technology exhibits at AHA? I am told that in times past, there were countless gifts. With today’s regulations, pharmaceutical companies are restricted from handing out significant presents. However, I always find it entertaining to see cardiologists who earn six-figure salaries lining up for free cups of coffee and jump drives.

I did not expect to see a Nintendo station in the technology hall. I was even more surprised to learn that the Wii system was endorsed by American Heart Association. I since have learned that early on, the endorsement spawned some controversy. Having some downtime and an interest in videogames, I chose to check out the display. I used the skateboarding simulator which not only made me work up a sweat, but also counted the calories that I was losing while skateboarding around the AHA hall (in simulated format, of course). In reality, attending the AHA is not for the unfit. The conference center here in Chicago is so vast that many sessions appear to be separated by several city blocks. One can get plenty of exercise before even entering the Nintendo station.

On our blog, Susan did an excellent job describing the findings of the heart failure studies that were presented yesterday and the discussions generated. Because we have common interests in heart failure, we both found these sessions insightful and inspiring. But does it not seem odd at times that the results of the late-breaking clinical trials have been released to the press several hours before the discussants present it to their peers? When Dr. Keith Aaronson was describing his group’s excellent study of the HeartWare HVAD, I already knew the results from an email I received earlier in the day. It is like knowing when you watched The Sixth Sense for the first time (spoiler alert) that Bruce Willis was already dead.

The RAFT study continues to suggest that CRT is applicable to more and more of our patients. This has created a lot of buzz among the attendees of the session, as it is clearly a relevant finding to general cardiologists, heart failure docs, and EPs.

But let’s pose another question to our readers — after going to these sessions, how soon do you change your practice? Obviously, some of this is governed by guidelines and coverage. But are you happy to alter your practice based on the presentations you see at AHA, or do you wait for the report to be formally published? In 2009, this was an area of controversy when some findings presented at the ESC for CURRENT OASIS 7 were discrepant with those in the published study. But this, by and large, is the exception.

So when are you going to start placing BiV-ICD in NYHA Class 2 patients? When are you going to open up the prescription pad and write down eplerenone? While you muse about that, I am off to play some more games on my AHA-endorsed Wii.

November 15th, 2010

Let’s Bring CLOSURE to This Debate About PFO Treatment

Richard A. Lange, MD, MBA

In this blog, Rick Lange tells us how he would answer FAQs about PFO closure to prevent stroke.

The controversy:

Based on retrospective and nonrandomized studies, many physicians are convinced that percutaneous patent foramen ovale closure can reduce rates of cryptogenic stroke and transient ischemic attack. Although PFO closure devices are approved for stroke prevention in Europe and Canada, the FDA has not approved them for this indication in the U.S. Despite the lack of trial evidence, the number of percutaneous PFO/atrial septal defect closures in the U.S. increased almost 50-fold from 1998 to 2004, according to a recent study, while the number of surgical PFO/ASD closures was unchanged. The estimated percentage of PFO/ASD closures performed percutaneously in the U.S. increased from 18.5% to 92.5%.

In about 100 sites in the U.S. and Canada, 909 patients with a stroke and/or TIA due to presumed paradoxical embolism through a PFO were randomized to receive medical therapy alone or PFO closure with the STARFlex Septal Closure System followed by medical therapy. The rate of the primary endpoint — stroke or TIA at 2 years — did not differ significantly between the two groups (5.5% in the PFO-treatment group vs. 7.7% in the control group). Stroke recurrence at 2 years was 3% in both groups.

Was there a problem with the device?

Not likely, since the rate of adverse events with the closure device was low, and it was used successfully to close more than 85% of PFOs.

Why wasn’t PFO closure more effective than medical therapy?

Although PFOs are present in as many as 30% of individuals, paradoxical embolism through a PFO is rarely the cause of cryptogenic stroke. Furthermore, medical therapy can be quite effective at preventing paradoxical emboli.

Does this bring closure to the issue?

It does for me. However, individuals who are convinced that PFO closure is important will likely want corroborative studies. Several ongoing trials using other closure devices are in progress: the Helex septal occluder (Gore Medical) is under investigation in the multinational REDUCE study; the Amplatzer closure device (AGA Medical) is under investigation in the North American RESPECT trial and the European and Australian PC Trial; and the CLOSE study , which does not specify a particular device, is underway in France.

Where do you stand? For which, if any, patients with PFO would you recommend percutaneous closure?

November 15th, 2010

An Exceptional Late-Breaking Session

Susan Cheng, MD

Several Cardiology Fellows who are attending this week’s AHA meeting are blogging together on CardioExchange. The Fellows include Susan Cheng, Madhavi Reddy, John Ryan, and Amit Shah. Check back often to learn about the biggest buzz in Chicago this week — whether it’s a poster, a presentation, or the word in the hallways. You can read the preceding post here.

To start, I should confess that I normally avoid late-breaking sessions like the plague. I’m not a huge fan of massive impersonal venues, the good presentations are often on data that were already published the same day, and I usually don’t find the discussions to be so enlightening. But this Sunday afternoon’s late-breaking session (which featured the RAFT, ADVANCE, EMPHASIS-HF, and ASCEND-HF trials) was actually a fantastic learning opportunity — and not just because of the science.

I decided to go to this session for two main reasons. First, it was focused on heart failure, a rapidly expanding problem in cardiology that everybody knows is in dire need of new, innovative therapies. Second, I knew the research was going to be compelling (given what I’d seen of the same-day publications), and I wanted to see if my own lingering questions about the data might be addressed in the panel discussion.

As expected, several hot topics in heart failure were covered. And, as it turns out, the moderated discussions were really informative. But what made the session extra-special were the little things that happened outside the main content being presented…

To start, two discussants suffered from IT problems that caused their slides to be either missing or incorrect. This caused quite a bit of on-stage awkwardness, although both discussants were eventually able to do their part without the need for slides. So I learned that the mishap of malfunctioning slides isn’t something that only happens to fellows — and that even plenary speakers can be caught off guard when this happens.

Then, in addition, I also began to take notice of whether or not the speaker was presenting from memory or reading off notes. I guess the reason I was paying such close attention to this was because I recently helped a friend prepare last-minute for her AHA oral presentation. She was absolutely convinced that she needed to have everything memorized and, although I used to make a habit of doing the same, I wasn’t sure it was really necessary. Now, having observed what the plenary speakers do, I would definitely say it’s not necessary — and perhaps not even preferred. If somebody is really pressed for time before their big talk, I think I’d prefer that they spend their prep time honing the content of their talk rather than memorizing less-polished material. And then, if their slides were to malfunction, they’d still be able to read off their notes.

Finally, I thought it was interesting that, at this particular session, most attendees stayed until the very end. In late-breakers that I’ve been to before, there is usually something of a mini-exodus after every other speaker, depending on what’s popular. For instance, the moment after the ARBITER presentation ended at last year’s AHA, it felt like more than 200 people just got up and started walking out of the auditorium (a common side effect of the large impersonal venue) — which made me feel a bit sorry for the subsequent speakers lined up for that session. But at this session, even though the last presentation was not the most interesting of the whole line-up, relatively few people left before it was over. Then I realized it was probably because Eugene Braunwald was the discussant. Pretty darn smart of the moderators to order the presentations that way.

So, I guess I learned 3 things from this session, beyond the science presented: Always be prepared to do a talk in case the slides malfunction. It’s okay to read from notes. And, if you want people to stay to the end, get Braunwald to be the last speaker.