January 10th, 2011

World’s First Drug Eluting Bioresorbable Stent Gains CE Mark Approval

Larry Husten, PHD

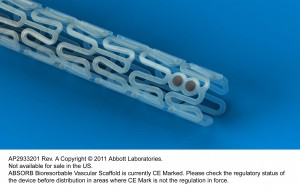

Abbott announced today that it had received CE Mark approval for Absorb, its bioresorbable vascular scaffold (BVS) device. The device props a narrowed coronary artery open but then dissolves within 2 years, leaving the patient without a permanent implant. One hope for the device is that it will allow stent patients to safely discontinue dual antiplatelet therapy at an earlier time.

“Abbott’s Absorb has the potential to change the way patients with coronary artery disease are treated, as it does what no other drug eluting coronary device has been able to do before – completely dissolve and potentially restore natural vessel function in a way not possible with permanent metallic implants,” said Patrick Serruys, in an Abbott press release.

Abbott said that the new device will be available “in select sizes to a limited number of centers in Europe later this year and into 2012.” A full commercial launch in Europe will not take place until late 2012. Abbott also announced plans for a 500-patient European study comparing Absorb to Abbott’s Xience Prime. A global trial is also planned for later in the year.

January 6th, 2011

The Shame of Removing Reimbursement for End-of-Life Discussions from Health Care Reform

Barry M. Massie, BA (Harvard), MD (Columbia P&S)

My recent postings have been about heart failure mortality statistics. Dry stuff!

It’s not that I am fixated on death, but yesterday, I learned that CMS (Medicare) has decided not to pay for discussions with patients about prognosis and planning end of life care. Reimbursement for such discussions was a key aspect of the health care reform legislation passed this year, and was widely mischaracterized as establishing “death panels.” I cannot imagine a legitimate justification for this rescission to the law. Patients and families are eager for this information, and it is important to them that it be available. Most want to understand their conditions and the options available to them. It is also invaluable to their physicians and other health care providers to know and understand their patients’ preferences. None of us want to cause unnecessary discomfort—nor, for that matter, would we want to experience it ourselves. I can think of no reason why patients who wish to be informed and participate in such decisions should be denied this option. Indeed, it is unethical and contrary to our Hippocratic oath not to ask patients and their families what they would want to have done at all stages of illness. We all obtain “informed consent” and discuss alternative options before certain tests and procedures.

End of life care should be no different. Indeed, one could consider it grounds for malpractice to expose patients to unnecessary suffering by not engaging in such discussions. Perhaps such ethical and legal risk would encourage practitioners to have these discussions without payment. Speaking as a heart failure specialist, there is a wide spectrum of potential management approaches to patients with severe heart failure who have not responded to optimal treatment regimens. These range from experimental drugs to device implantation, mechanical assist devices, and transplantation. But for those who are continuously short of breath and uncomfortable, or unable to take care of themselves and have exhausted treatment options, there are also choices that should involve patients and their families.

In my view, this rescission reflects a lack of courage on the part of those responsible, and they should be ashamed. In short, appropriate and ethical decisions have been defeated by dishonest sound bites (e.g., the above-mentioned “death panels”). For this, everyone (patients, families, medical personnel who will have to participate in patients’ unnecessary suffering, and the public which will have to ultimately pay for the exorbitant costs of end of life care) will suffer.

January 6th, 2011

Bevacizumab in Breast Cancer Linked to Increase in Heart Failure Risk

Larry Husten, PHD

A meta-analysis in the Journal of Clinical Oncology suggests that bevacizumab (Avastin) significantly raises the risk for heart failure when given to patients with breast cancer. Toni Choueiri and colleagues analyzed data from 3,784 patients and found a significant increase in the incidence of heart failure among those taking bevacizumab compared with those taking placebo (1.6% versus 0.4%).

In an accompanying editorial, Nitin Verma and Sandra Swain write that “the results of this meta-analysis should be interpreted with extreme caution.” They point out the limitations of a meta-analysis with retrospectively collected HF data and strongly urge that “randomized prospective trials to determine the magnitude of the potential risk, time of onset, and reversibility of heart failure with bevacizumab” be performed.

January 5th, 2011

Study Finds Mixed Long-Term Results for AF Catheter Ablation

Larry Husten, PHD

Long-term results after catheter ablation for AF are decidedly mixed, according to the longest study yet to follow patients after the procedure. In a report in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Rukshen Weerasooriya and colleagues followed 100 patients treated at a French hospital for 5 years. After a single procedure, the rates of arrhythmia-free survival were 40% at 1 year, 37% at 2 years, and 29% at 5 years. Patients underwent a median of 2 procedures during the study period. Following the last catheter ablation procedure, the rates of arrhythmia-free survival were 87% at 1 year, 81% at 2 years, and 63% at 5 years. Three patients had cardiac tamponade requiring drainage during the procedure. Patients with long-standing persistent AF were more likely to have a recurrence than other patients.

Results in the real world may be even worse than those reported in the study since, the authors noted, their “study population was not representative of patients with AF at large, as it consisted predominantly of younger, healthier, nonobese patients with relatively smaller atria and paroxysmal or recent progression to persistent AF.”

The authors concluded: “Although most recurrences transpire over the first 6 to 12 months, a slow but steady decline in arrhythmia-free survival is noted thereafter, even after 3 or more years of apparent arrhythmia control. Such long-term follow-up data should be openly discussed with patients, factored into management decisions, and incorporated into cost-effectiveness models that assess the merits of an ablation approach.”

January 4th, 2011

Study Suggests Large Proportion of ICD Implantations Lack Firm Evidence Base

John Spertus, MD, MPH

Study Summary by Larry Husten: An analysis in JAMA of the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) shows that a substantial proportion of ICD implantations are not supported by a firm evidence base. Sana Al-Khatib and colleagues examined data from 117,707 patients who received ICDs between January 1, 2006 and June 30, 2009, and found that 22.5% of implantations were not evidence based.

Newly diagnosed heart failure accounted for more than half of the non-evidence-based implantations. People with MI within 40 days or with NYHA Class IV symptoms accounted for most of the other cases.

Compared with those who received an evidence-based ICD, in-hospital death was higher in patients who received an ICD without a firm evidence base (0.57% vs 0.18%, p<0.001) and post-procedural complications were also higher (3.23% versus 2.41% (p< 0.001).

Electrophysiologists had a lower rate of non-evidence-based implants than other physicians. Patients who received non-evidence-based ICDs were older, sicker, more likely to belong to a racial minority (other than black), and were more likely to receive a dual-chamber ICD.

The authors comment that although the absolute difference in complications between the two groups was “modest, these complications could have significant effects” on the patients. “Importantly, these complications resulted from procedures that were not clearly indicated in the first place. While a small risk of complications is acceptable when a procedure has been shown to improve outcomes, no risk is acceptable if a procedure has no demonstrated benefit.”

In an accompanying editorial, Alan Kadish and Jeffrey Goldberger write that the findings “should be used to inform public health policies toward the appropriate use of this life-saving but expensive technology.”

Commentary by John Spertus:

The paper in this week’s JAMA by Al-Khatib and colleagues analyzed the NCDR ICD registry to describe the prevalence, inter-hospital and inter-specialty variability, and in-hospital outcomes associated with non-evidence-based implantation of ICDs. Their finding that almost a quarter of ICD implantations are not evidence-based, with tremendous site variability, is very important. The accompanying editorial notes several potential challenges with the study – that I will not repeat – but I think that there are several key additional issues that need to be emphasized that were not noted by the editorialists.

First, this type of analysis is an enormous and important extension of previous work from procedural registries, such as those of the NCDR. Procedural registries have traditionally focused upon the procedural complications associated with treatment. An enormous goal for improving the quality of care for cardiac disease is to shift our focus from “was the procedure done well?” to “did we do the procedure in the right patient?” The ACC has started to move in this direction with the creation of Appropriate Use Criteria, but those do not yet exist for ICD devices. Therefore, the authors examined whether or not there was evidence to support implantation in certain subsets of patients.

Finding that almost 1 in 4 procedures were done for patients without evidence to support their use is impressive and concerning. However, I believe that there are 2 types of circumstances in which evidence doesn’t support the use of a treatment. The first is when those patients were not included in the clinical trial. As physicians, we recognize that clinical trials have extensive inclusion and exclusion criteria (to minimize sample size and costs of a study) and use our judgment to extend the findings to patients we clinically feel are similarly likely to benefit. For example, the vast majority of initial DES studies were performed in patients with single-vessel coronary disease and we all feel comfortable using them in patients with multi-vessel disease. A much more concerning scenario, however, is when patients were included in a study and no benefit was observed. For example, the DINAMIT investigators proved that there was no benefit from ICD implantation within 40 days of an MI. Yet this was the second most common “non-evidence-based” indication of ICD implantation in this study. Providing an expensive and risky treatment to patients in whom we know that there is no benefit makes any complication or risk from the treatment unjustifiable and deserves a major effort to eradicate this practice so that we can systematically provide safer, more cost-effective care to our patients.

Second, the authors note that the practice of implanting “non-evidence-based” devices has changed little, even though the NCDR ICD registry provides reports to sites about their rates of these treatment patterns. Al-Khatib and colleagues note that “Via quarterly reports, the NCDR shares data with participating hospital sites on their rates of approved indications for primary prevention ICD implantations…” To me, this is the most concerning finding of the study. Although the authors suggest more education is needed to minimize the occurrence of “non-evidence-based” implantations, such educational interventions are known to be very weak. In fact, the NCDR has gone beyond this by already providing sites with their own performance data. My question is what are the sites doing with these data? It is a phenomenal opportunity to know what your hospital is doing, but this has had no apparent impact on practice. I believe that the key challenge raised by this article is that we need to develop improved methods for using these data about our selection practices. Do we need to start reporting at an individual operator level? Do we need to start holding physicians accountable? Should there be a prospective worksheet to document why a physician chooses to defy the evidence and treat a patient? Should there be mandatory “secondary opinions” prior to treatment to minimize this practice in the future? These are key issues facing our profession and we need to start addressing them.

Finally, the authors have made much of the lower rates of “non-evidence-based” implantations by electrophysiologists. Personally, I believe that this is a distraction. The absolute difference in rates between specialties is ~4%, except for cardiothoracic surgeons who had a higher rate. Yet 1 in 5 of electrophysiologists’ cases were done in the absence of evidence! This underscores that all providers have a huge opportunity to improve. In fact, the actual number of “non-evidence-based” devices implanted by electrophysiologists (about 15,475) is more than twice the rate of the “non-evidence-based” devices placed by non-electrophysiologist cardiologists (about 6,870), cardiothoracic surgeons (about 1,048) and other clinicians (about 1,697) combined. No specialty is immune from the opportunity to improve and we all need to work collaboratively to improve the selection of patients for invasive treatments so that we can improve the quality of care, at the least possible costs, for all of our patients.

January 3rd, 2011

PLATO CABG Substudy Raises Hope and Questions

Larry Husten, PHD

The much-anticipated CABG substudy from the PLATO (Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes) trial comparing ticagrelor to clopidogrel in ACS patients has been published online in JACC. About 10% of the 18,624 patients enrolled in PLATO underwent CABG. The substudy reports on the 1,261 who received the study drug within 7 days prior to their surgery. The study protocol called for ticagrelor to be withheld for 24-72 hours and clopidogrel to be withheld for 5 days prior to CABG.

The reduction in the primary endpoint (a composite of death from vascular causes, myocardial infarction, or stroke) was not significant but, wrote the authors, “was consistent with the results of the whole trial” (10.6% in the ticagrelor group versus 13.1% in the clopidogrel group, p=0.29). There was a significant reduction in total mortality (9.7% versus 4.7%, p<0.01) and cardiovascular death (7.9% vs 4.1%, p<0.01). In addition, there was a surprising lack of any differences in CABG-related major bleeding, although in the overall trial ticagrelor was associated with more bleeding.

The authors write that the mortality findings were “striking and also explained about a quarter of the mortality reduction in the whole trial. The finding that the excess mortality with clopidogrel was unrelated to differences in the rates of bleeding raises the suspicion that clopidogrel treatment might be associated with other specific risks in association with major surgery.”

In an accompanying editorial, David Schneider speculates about the striking findings of the substudy. He writes that the difference in mortality and the lack of difference in bleeding may be explained in part by the greater antiplatelet efficacy of ticagrelor, the time difference in discontinuation of therapy, the reversability of ticagrelor’s P2Y12 binding, and inhibition of adenosine uptake into erythrocytes.

January 3rd, 2011

Medicare: The MasterCard That Keeps On Giving

Shanti Bansal, MD

In the cardiac catheterization lab one Tuesday morning, I encountered a situation that made me reflect on a bit of 18th-century British history.

At that time, the British government was overburdened with prisoners. A plan was hatched for sea captains to transport many of them to Australia. Due to poor conditions, up to one third died on the voyage. Politicians and clergy members desperately urged the sea captains to improve the conditions, but survival rates changed little. But then an economist suggested paying the captains for every prisoner who made it to Australia rather than for each one who boarded a boat. Survival quickly improved to 99%.

Back in the catheterization lab, there were no British prisoners — just a slim, gray-haired man with bristling facial hair lying on a stretcher in front of me. With his chart in hand, I greeted this Mr. Johnson and asked him how he had come to the attention of Dr. Attending, an interventional cardiologist.

“I was seeing him for my cholesterol,” Mr. Johnson replied, “and then I started to get a little short of breath after going up a few flights of stairs. He ran some tests, and next thing I know I’m here. I’m sure that any blockages they fix will prevent the next big heart attack, so I’m not worried.”

I perused a note written by Dr. Attending: “Mr. Johnson, a 75-year-old gentleman, remains highly symptomatic from shortness of breath. Since this may be his anginal equivalent, I will recommend a cardiac catheterization for further evaluation and treatment.”

Struck by the disparity between the clinical situation and the note, I nevertheless passed the consent form to Mr. Johnson, who signed it. He was whisked away to the catheterization lab, and with Dr. Attending by my side, we began the procedure. The catheter engaged the left-main and then the right coronary artery easily and accurately. The contrast illuminated the arteries like glow sticks on a sobering night. The right coronary was totally occluded.

“Well, this is clearly the cause of his shortness of breath!” Dr. Attending exclaimed. “We need to fix it!”

In the ensuing hours, we deployed a balloon pump to push blood over the diamond drill of the roto-rooter. It cut through the cemented plaque with hydraulic precision along the tracks of countless coronary wires. After the procedure, Mr. Johnson was admitted for a brief stay in the ICU and, later, to the hospital floor. When I saw him walking about in his standard-issue navy blue slippers, I asked him how he was doing.

“Good,” he said. “Still a bit short of breath though. I’m happy to be going home today.” The case left me feeling uneasy.

Did our complex medical procedure decrease Mr. Johnson’s risk for morbidity or mortality? If not, did we improve his quality of life? Has caring for patients become more about the journey than the destination? Can we instead give physicians and health care providers incentives to focus on outcomes, as the 18th-century British sea captains eventually received? In the 21st century, my experience with Mr. Johnson’s care read like the script of a MasterCard commercial:

Complex medical procedure plus hospitalization: $63,535.00

Outpatient follow-up: $56.50

Navy blue hospital slippers: $5.50

Judicious medical care: Priceless

December 28th, 2010

Looking Forward to 2011

CardioExchange Editors, Staff

| CardioExchange invited a wide range of members−researchers, teachers, private practice clinicians, and fellows−to offer predictions for 2011. We summarize their lists here and offer a running scorecard. Click the authors’ names to read the full posts. The same CardioExchange members give us their impressions of the most important developments in cardiology in 2010, and you can see a summary of those here. | |

| What are your predictions for the year? Where have our Nostradamus’ gone wrong?

|

|

1. Federal investigation of overuse of stents 2. ACC announces that it will no longer accept funding from device manufacturers 3. Efforts to revise healthcare legislation will fail |

|

1. More people on statins as they go generic, but fewer actually reaching lipid targets 2. Use of biomarkers and pharmacogenomic strategies to mitigate CV risk will take a back seat 3. New primary and secondary prevention guidelines will be more aggressive |

|

1. Patriots beat Eagles in the Superbowl 2. ATP IV and JNC 8 out by next AHA 3. CETP inhibition with dalcetrapib is successful in ACS patients. 4.IMPROVE-IT shows a modest benefit 5. Sanjay Kaul finds a trial design and a DSMB he likes! |

|

1. Government scrutiny of interventional cardiology will increase 2. Platelet reactivity assays to guide antiplatelet therapy after PCI will get even more confusing 3. New guidelines on which patients benefit from revascularization and what type (PCI vs. CABG) will change little |

|

1. Increased focus on costs, increased costs, and emergence of de facto rationing 2.Increased scrutiny of cardiac images and procedures yields underutilzation 3. Further consolidation among cardiology practices and hospitals |

|

1. Meaningful payment reform is realized 2. ACC will work to implement point-of-care access to appropriate use criteria for imaging tests 3. Observational studies will show that the vast majority of interventional procedures are performed appropriately |

|

1. No pill or surgery will treat obesity effetively 2. Coronary stents will surpass ICDs in regulatory oversight 3. AF will stay on the front page of cardiology news |

|

1. Healthcare reform is not overturned but implemented slowly 2. More groups move to employed status in response to cost-cutting, EHR requirements, etc. 3. Hospital to Home National Quality Improvement Initiative is a big success |

|

1. 2011 will see a shift away from warfarin 2. More healthcare delivery studies focused on decreasing costs and improving quality 3. Will JNC-8 have dramatically new recommendations? |

|

1. End of the independent practitioner 2. Increased focus on the harm caused by unnecessary radiation exposure 3. Increasing public scrutiny around conflict of interest issues |

|

December 24th, 2010

A Look Back at 2010

CardioExchange Editors, Staff

| CardioExchange invited a wide range of members−researchers, teachers, private practice clinicians, and fellows−to give us their impressions of the most important developments in cardiology in 2010. We summarize their lists here and offer a running scorecard. Click the authors’ names to read the full posts. The same CardioExchange members offered predictions for 2011, and you can see a summary of those here. Also, for comparison, check out the AHA list of the top 10 advances in cardiovascular research this year. | |

| What would your choices have been? Any sins of inclusion or exclusion here in your opinion? Join the conversations.

|

|

|

|

|

1. Rosiglitazone withdrawal in Europe and restriction in the U.S. 2. Approval of dabigatran 3. ACCORD lipid study |

|

1. ACCORD Lipid 2. ACCORD BP 3. Meta-analysis of statins in high-risk primary prevention and all-cause mortality. |

|

1. Approval of dabigatran 2. JUPITER/Meta-analysis of women from prevention trials study of women with high CRP or dyslipidemia 3. ACCORD BP and ACCORD Lipids |

|

1. CREST trial (Stenting versus Endarterectomy for Treatment of Carotid-Artery Stenosis) 2. PARTNER trial (Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Implantation for Aortic Stenosis in Patients Who Cannot Undergo Surgery) 3. COGENT trial (Clopidogrel with or without Omeprazole in Coronary Artery Disease). |

|

1. PARTNER trial (Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Implantation for Aortic Stenosis in Patients Who Cannot Undergo Surgery) 2. RAFT (Resynchronization–Defibrillation for Ambulatory Heart Failure Trial) 3. DEFINE trial (Determining the Efficacy and Tolerability of CETP Inhibition with Anacetrapib) |

|

1. PARTNER trial (Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Implantation for Aortic Stenosis in Patients Who Cannot Undergo Surgery) 2. The Symplicity HTN-2 trial 3. DEFINE trial (Determining the Efficacy and Tolerability of CETP Inhibition with Anacetrapib) |

|

1. Approval of dabigatran 2. Mark Midei story (Maryland doctor accused of implanting hundreds of unnecessary stents) 3. Percutaneous therapy for valvular heart disease (most notably the PARTNER trial) |

|

1. Approval of dabigratran 2. Passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act 3. Mark Midei story (Maryland doctor accused of implanting hundreds of unnecessary stents) |

|

1. Aldosterone antagonists continue their winning streak (RALES, EPHESUS, and EMPHASIS) 2. Migrating cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) into milder heart failure (RAFT) 3. Disappointing data on remote monitoring to improve heart-failure outcomes (Tele-HF and TIM-HF) |

|

1. Study on effects of CYP2C19 genotype on outcomes of clopidogrel treatment 2. PARTNER study (Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Implantation for Aortic Stenosis in Patients Who Cannot Undergo Surgery) 3. Studies showing risk of low-dose ionizing radiation from medical imaging procedures |

|

1. ACGME releases new duty hour rules 2. Aldosterone antagonists continue their winning streak with publication of EMPHASIS-HF 3. The merging of cardiology practices and hospitals. |

|

![]()

| *** Vote Tally *** | |

| VOTES | TOPIC |

| 5 | PARTNER trial |

| 4 | Dabigatran approval |

| 3 | ACCORD Lipid |

| 2 | ACCORD BP |

| 2 | RAFT trial |

| 2 | Risk related to low-dose ionizing radiation from medical imaging |

| 2 | Mark Midei story (doctor accused of implanting unnecessary stents) |

| 2 | Aldosterone/EMPHASIS trial |

| 1 | JUPITER substudy in women |

| 1 | Meta-analysis of statins for high-risk primary prevention in women |

| 1 | CYP2C19 genotype/clopidogrel resistance study |

| 1 | DEFINE trial |

| 1 | Rosiglitazone restrictions |

| 1 | Healthcare reform |

| 1 | Remote monitoring of HF patients (Tele-HF and TIM-HF) |

| 1 | Study on effects of CYP2C19 genotype on outcomes of clopidogrel treatment |

| 1 | New ACGME duty hour rules |

| 1 | Merging of cardiology practices and hospitals |

| 1 | COGENT trial |

| 1 | CREST trial |

![]()