April 12th, 2011

Two Studies Try to Improve Risk Prediction for Kidney Disease Progression

Larry Husten, PHD

Two papers presented at the World Congress of Nephrology and simultaneously published online in JAMA raise hope for better tools to calculate the risk for developing kidney failure, but the techniques are not yet ready for clinical use, according to an accompanying editorial.

In the first study, Carmen Peralta and colleagues evaluated a triple-marker strategy combining creatinine, cystatin C, and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) using data from 26,643 U.S. subjects enrolled in the REGARDS (Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) study. They found that cystatin C and albuminuria “were both strongly and independently associated with all-cause death among persons with or without CKD defined by creatinine-based estimated GFR.”

In the second study, Navdeep Tangri and colleagues used data from two Canadian cohorts of patients with CKD to develop and validate a model to assess the risk for disease progression using routinely measured variables. The model they developed included age, sex, estimated GFR, albuminuria, serum calcium, serum phosphate, serum bicarbonate, and serum albumin and was more accurate than a simpler model in the validation cohort.

In an accompanying editorial, Marcello Tonelli and Braden Manns say that neither study should be considered definitive, but “they provide proof of concept for 2 new methods that could be used to enhance prognostic power.” Both studies, they write, “are novel and important.” But the bigger challenge is to “demonstrate that using better risk prediction tools will lead to clinically meaningful benefit for patients.”

April 11th, 2011

Phentermine-Topiramate Combination Yields Significant Weight Loss

Larry Husten, PHD

The experimental diet drug combination of phentermine and topiramate demonstrated “robust efficacy” in CONQUER, a large new trial published online in the Lancet. The trial’s results come after a year in which the FDA turned down three investigational diet drugs (including Qnexa, the phentermine-topiramate combination used here) and removed the diet drug sibutramine from the market, leaving only one diet drug, orlistat, on the market.

Kishore Gadde and colleagues randomized 2,487 overweight or obese patients who had at least two comorbidities to placebo or a high- or low-dose combination of phentermine and topiramate for 56 weeks.

At 56 weeks, weight loss was

- 1·4 kg in the placebo group;

- 8·1 kg in the low-dose combination group (p<0.0001);

- 10·2 kg in the high-dose combination group (p<0.0001).

At least 5% weight loss was reached by:

- 21% of patients in the placebo group;

- 62% of patients in the low-dose group (p<0·0001);

- 70% of patients in the high-dose group (p<0·0001).

The investigators also report improvements in blood pressure, lipids, glucose control, and inflammatory markers.

The most common side effects associated with the experimental combination were dry mouth and paraesthesia. The investigators conclude that the side effects either were tolerable (e.g., taste disturbance) or could be managed by discontinuing the drug (nephrolithiasis, metabolic acidosis, and cognitive and psychiatric adverse events).

The authors write that the drug combination “could be a valuable addition to the small arsenal of effective obesity treatments that are available to family doctors.”

April 11th, 2011

PARTNER A: An Investigator’s View

Michael Mack, M.D.

CardioExchange welcomes Dr. Michael Mack to discuss the results of the PARTNER study of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) versus surgical aortic valve replacement (AVR) in patients with aortic stenosis, which were just released at the ACC meetings in New Orleans. Dr. Mack was one of the principal investigators in this and the recently published PARTNER B study of TAVI in AS patients who were turned down for AVR. Questions to Dr. Mack come from CardioExchange’s Dr. Richard A. Lange and Dr. L. David Hillis.

Background: The PARTNER study showed that TAVI was noninferior to AVR with respect to 1-year mortality in high-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis.

Lange and Hillis: The investigators enrolled patients considered at high risk for adverse effects of AVR (predicted operative mortality, ≥15%), but the 30-day mortality with AVR was only 6.5%. Is AVR better and safer than we appreciate, or are we simply poor at identifying “high-risk” patients? Can we conclude that PARTNER shows that TAVI is an acceptable alternative to AVR for the lower-risk patient?

Mack: The lower observed mortality in the surgical arm could have resulted from either surgery performing better than expected or the risk model overpredicting risk. A study by Thourani and colleagues published in the Annals of Thoracic Surgery in January 2011 reviewed procedural results in very high-risk patients at four PARTNER sites before the trial. The findings demonstrated an expected mortality of 16% and an observed mortality of 16%. Therefore, I feel that the results in the PARTNER study sites were exceptional in the surgery arm. The reason is probably that the surgery was performed in high-volume valve centers with experienced surgeons. The number of surgeons at each PARTNER site was limited to those qualified as high-risk surgeons. Using an STS-predicted mortality of about 4% would include the upper 25th percentile of risk; therefore, in my personal opinion, the as-treated mortality of 5.2% in the TAVI arm in the PARTNER A cohort justifies a hypothesis of equipoise and a trial in this lower-risk population. Having said that, the results of PARTNER A and B were obtained in inoperable and very high-risk patients, and any extrapolation of those results to a lower-risk population and to centers other than high-volume valve centers with a multidisciplinary heart team in place is not justified.

Lange and Hillis: Considering the patients who were included in PARTNER (i.e., elderly, high risk patients) and those who were excluded (i.e., with bicuspid valve, CAD needing revascularization, advanced ileofemoral disease, etc.), what proportion of AS patients currently undergoing AVR would be serious candidates for TAVI?

Mack: Current screening logs of PARTNER study sites indicate that about one third of patients screened were enrolled. Reasons for exclusion included extreme frailty, bicuspid aortic valve disease, not meeting trial criteria, and unwillingness to enter in to an investigational trial. In addition, a fair number of patients died during the workup process or while on the waiting list for the trial. In my opinion, the proportion of screened patients who would be candidates for TAVI outside the confines of a trial might increase to 50% at most. It should be noted that the patients studied (i.e., inoperable or very high-risk) constitute approximately 10% of the current AVR surgical population.

Lange and Hillis: The complication rates for both the AVR- and TAVI-treated patients are impressively low in PARTNER. Since AVR is an established therapy (i.e., the learning curve is over), will TAVI still compare favorably to AVR when it goes “real world”?

Mack: The results of the TAVi arm are especially impressive when it is noted that 19 of the 26 study sites had no previous TAVI experience and that it was an early-generation device. It is true that the arms were somewhat imbalanced: an early-generation technology and technique was being compared with a mature one. However, it should be noted that these results were obtained in high-volume valve centers with experienced structural interventionalists working with a multidisciplinary heart team. I am very concerned that these results are not reproducible at centers where the same treatment paradigm is not in place. As evidence for this, it should be noted that the data from national registries in France and Germany are somewhat worrisome. The 30-day mortality of TAVI procedures continues to be around 8%–10%, even as the logistic EuroSCORE risk of the patients decreases. The fact that the mortality results are not improving and remain quite high may be due to the widespread expansion into the real world, where standalone cardiology centers are often capable of only a transfemoral approach. In the continued access arm of the PARTNER trial in the United States, approximately 50% of the procedures are being performed via a transapical approach, which suggests that a multidisciplinary heart team with all access options available is much more likely to choose a non-transfemoral approach. I am somewhat concerned that the current registry results in Europe suggest that the current PARTNER results will not be reproduced in the real world.

Lange and Hillis: In comparison with AVR, TAVI was associated with a higher incidence of stroke, vascular complications, and paravalvular leak but a lower incidence of atrial fibrillation and bleeding. Are these fair trade-offs? Since most strokes do no not appear to be procedure-related, will improvements in valve design reduce the risk for this complication?

Mack: Currently, the incidence of stroke and vascular complications continues to be an issue of concern with TAVI. We are pursuing in-depth analysis of the stroke data to determine associated factors and whether embolic protection might afford any improvement. We also hope to determine whether there is an ongoing hazard risk after the initial 30-day period. The vascular complication rate appears to be decreasing in our experience and that of other centers, due to newer-generation delivery devices and more experience — both with the procedure and with managing complications — as well as the more-liberal use of the transapical approach in borderline situations. The incidence of paravalvular leak is an ongoing concern and obviously needs long-term follow-up. Although early on there does not seem to be a detrimental aspect to this, it is way too early to assume insignificance.

Lange and Hillis: Without long-term follow-up data available, should we be offering TAVI to younger (i.e., 60-70-year-old) patients?

Mack: I think that offering TAVI to a 60- or 70-year-old patient is currently too much of a stretch. Due to the lack of long-term follow-up data, the higher incidence of bicuspid aortic valve disease in younger patients, and the current mortality and complication rate of TAVI, offering it to this population is not justified. Surgical AVR mortality in this patient group is currently 1% in experienced centers. Studying a population aged 70 or older with multiple comorbidities, such that the predicted mortality is in the range of 4% to perhaps 8%, would probably be more realistic. However, if commercial approval happens before the results of such a trial are available, offering TAVI to patients outside of those similar to the trial study population is not justified.

For more of our ACC.11 coverage of late-breaking clinical trials, interviews with the authors of the most important research, and blogs from our fellows on the most interesting presentations at the meeting, check out our Coverage Roundup.

April 10th, 2011

Questioning the Guidelines

scottwright109 and Hansie Mathelier, MD

CardioExchange welcomes R Scott Wright, the chair of the recently published focused update of the ACC/AHA Unstable Angina/NSTEMI guidelines. Dr. Wright generously agreed to answer questions about the guidelines posed by the CardioExchange editors.

CardioExchange Editors: For clinicians reading this guidelines update, what would you highlight as the most important new or revised recommendations that should be considered in current practice?

Dr. Wright: I think there are several things of interest to practicing clinicians in the revisions we have published including:

- Clarification regarding the role and timing of invasive management in ACS patients. New data continue to emphasize the benefit of early invasive management in high risk ACS patients as well as the appropriate role of initial medical stabilization in low and intermediate risk patients.

- Clarification, using the latest evidence based medicine, on which patient subgroups should have dual anti-platelet therapy (DAPT) versus triple antiplatelet (TAPT) therapy. TAPT can be reserved for those who undergo PCI or at highest risk prior to PCI. We also highlighted the potential bleeding risks for TAPT and hope clinicians will think carefully and act responsibly when using TAPT.

- The potential benefit of invasive management in renal dysfunction as well as the paucity of evidence to drive an invasive strategy in those with severe renal dysfunction (CKD IV, V).

- The critical importance of using risk stratification tools to better understand individual patients’ short and longer term risks and how risk estimate influences selection of initial management strategies.

- The critical importance of every US hospital and provider to be engaged in quality improvement measures and to use systems approaches to manage, monitor and follow patients as well as drive innovation in health care system delivery. It is no longer acceptable to say your hospital should be in a registry. It should and so should you as a provider and the data you get back should prompt you to improve how you practice medicine and deliver care

- There are a lack of data to drive measuring platelet function and genotyping. Clinicians should only use these tools if such data will alter clinical decision making. This type of testing should not be done just to know the data. It is also important to understand that there is insufficient evidence currently available to say that knowing these data and changing the dose or type of thienopyridine prescribed will improve outcomes. We hope most clinicians will wait on the data from multiple, ongoing RCT’s examining these issues.

- The role of prasugrel in patients with ACS. We tried to follow the FDA package insert regarding how to use this agent as we felt the FDA weighed the evidence carefully. We hope that clinicians will be aware of the potential for bleeding and will avoid using it in the high risk subgroups identified by the package insert.

Editors: In light of more information provided from new research — but less definitive evidence and what appears to be fewer class A recommendations overall — what would you consider to be the main take home points for clinicians reading this update?

Wright: This is a great and insightful question. The astute reader will note that we downgraded the level of evidence for one recommendation, now adhering to a stricter standard set by the ACC Board of Trustees and endorsed by the Guidelines Governanance Task Force and our Working Group. We had heard a number of concerns by clinicians that some in industry were using previous guidelines recommendations to aggressively market products, perhaps not consistent with the spirit and intent of the 2007 edition.

Our goals with the 2011 revision were:

- to incorporate new evidence in a clinically meaningful way,

- to insist that more recommendations by backed by larger RCT evidence or multiple smaller RCT’s whenever possible,

- to try to focus the update on issues that are of clinical relevance to today’s practicing physicians, and

- to encourage clinicians to consider quality improvement participation.

Editors: Did the committee find it difficult to reach a consensus on controversial issues such as the role of prasugrel, platelet-function and genetic testing, and PPIs?

Wright: Yes, the committee thoroughly discussed, considered and vetted each of these issues. Our work was enhanced greatly by the large number of thoughtful, not-shy peer reviewers who challenged us on our first version and helped us clarify our thoughts and ideas. We had peer review from across the USA, Europe and Latin America. We also worked across specialty lines by having input from non-cardiologists: Heart Surgeons, internists, family physicians, ED physicians, Nurse practitioners and others. We met for a strategic review with our counterparts at the ESC and reviewed what each of our respective groups thought were key areas for improvement in the ACS guidelines. Finally, we shared our ideas with other working groups like the PCI task force so that we could gain from their expertise as well.

At the end of the day, there were very few slim majorities. My style of leadership was to build consensus and have at least a 2/3 majority on most things. I felt that we needed that degree of support to ensure we reflected the many faces of medicine fairly and did not have any one strong opinion or conflicted interest influencing things. My co-Chair Dr. Jeffrey Anderson was very helpful with his insight, leadership and experience at leading these types of working groups. Jeff deserves a lot of credit for our finished product.

We were aided in our work on PPI and Platelet function testing issues by the recently published consensus statements by the ACC/AHA. Those documents are well written, well referenced and offer practical advice. We thought their discussions were superb and did not deviate from them to any great extent. We also reviewed evidence presented as late as the ESC and AHA 2010 and incorporated new findings into our work.

Finally, we strictly enforced the ACC/AHA policy that those with a conflict of interest in any given area could not vote. The ACC Staff working with us were fantastic at helping us remain compliant with this and with the COI’s from our peer review group. No member of the working group with a COI ever tried to dominate discussion or push the revision in a given direction. I truly believe we used a fair, transparent and patient-centered process. Dr. William Mayo is quoted at my work place, the Mayo Clinic, as saying “The interests of the patients are the only interests to be considered…” It was a privilege to work with my fellow Task Force members as each of them reflected that value quite well.

Editors: What do you predict will be on the horizon for future updates to the UA-NSTEMI guidelines?

Wright: I am hopeful that several changes will come with the next full revision including:

- Requiring a higher percentage of the recommendations to be supported by RCT evidence,

- Making the guidelines more patient centric so that the clinician reading them will better understand how to apply them in everyday clinical scenarios,

- reduced redundancy within a specific guideline document and more harmony across guideline documents (for example, the PCI, STEMI and UA/NSTEMI guidelines) and

- continued emphasis on the use of quality improvement processes and registries to guide implementation, application and revision of evidence based practices as well as understand how such improvements reduce mortality.

April 8th, 2011

Who Might Merit the MitraClip?

Ted Feldman, MD

CardioExchange welcomes Ted Feldman, lead investigator for the EVEREST II study published earlier this week in the NEJM and presented at the ACC Scientific Sessions in New Orleans. Drs. Richard A. Lange and L. David Hillis, of CardioExchange, asked Dr. Feldman about the nuances of this randomized trial, in which percutaneous repair was compared with surgery in patients who had mitral regurgitation. We encourage you to offer your own questions and opinions.

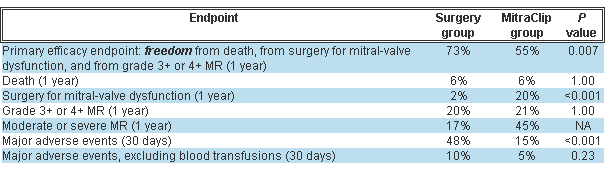

Background: In EVEREST II, 279 patients with moderately severe or severe mitral regurgitation (MR) were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to undergo either conventional surgery (valve repair or replacement) or percutaneous repair with the MitraClip, an experimental device. The device maker funded the trial.

Rates for selected trial endpoints appear in the table below.

Post-treatment MR severity improved in both groups but significantly more in the surgery group. About a quarter of the MitraClip group had significant MR prior to hospital discharge and were referred for surgery.

Post-treatment MR severity improved in both groups but significantly more in the surgery group. About a quarter of the MitraClip group had significant MR prior to hospital discharge and were referred for surgery.

Drs. Lange and Hillis: Before everyone and his dog signs up for training, tell us which MR patients are good candidates for percutaneous repair, and who should not undergo the procedure.

Dr. Feldman: Higher-risk patients are the clearest candidates for the MitraClip. A subgroup analysis from the trial points to the best outcomes in patients age 70 or older, those with LV ejection fractions <60%, and those with functional MR. We have substantial experience showing excellent clinical results in patients who are high risk for conventional mitral valve (MV) surgery, with safety outcomes equivalent to those in the randomized trial. Compared with a matched control group of high-risk registry patients (mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons [STS] risk score >12%), MitraClip recipients have a 45% lower rate of hospitalization during the year after therapy, and significantly better survival. Most of these patients have functional MR, and we find results to be the same for functional versus degenerative MR. Decisions about therapy for MR have always been complex and patient-specific; the MitraClip adds an option for many patients even if it also adds complexity. Of course, suitable valve anatomy is essential (the MR must arise from the A2–P2 scallops). For flail leaflets, the flail gap must be <10 mm and the flail width <15 mm.

Lange and Hillis: The procedure sounds like a real tour de force (i.e., general anesthesia, transthoracic echo, multiple interventionalists, and so on). How long does the procedure take, and how many physicians are involved?

Feldman: The mean procedure time now is between 1 and 2 hours. Single-clip cases often take less than 1 hour. Two-clip cases, which constitute 40% of the experience to date, typically take longer and are ordinarily closer to 2-hour procedures. In our earlier experience procedures took longer, and certainly the first few procedures for new operators each take several hours because the learning curve is substantial. The procedure is performed under general anesthesia with transesophageal echocardiographic guidance, so typically there are 2 interventional physicians, an echocardiographer, and an anesthesia team in the cath lab.

Lange and Hillis: Compared with conventional surgery, percutaneous treatment was associated with a higher 1-year incidence of subsequent surgery for MV dysfunction and of moderate or severe MR. Given that improvements in MR severity and LV end-diastolic volumes were greater with MV surgery than with percutaneous repair, why should patients be referred for percutaneous treatment?

Feldman: Of the MitraClip recipients in the trial, 78% did not require surgery after 2 years. Also at 2 years, the percentage of patients in NYHA class 1–2 is higher for the MitraClip group than for the surgery group (99% vs. 88%; P<0.05). Among those who have inadequate control of MR, surgery (including repair) remains an option. When the strategy of MitraClip with surgery (if needed) is compared with surgery as a first therapy, the two approaches show no difference in efficacy outcomes at 2 years. Patients prefer less invasive therapy, as reflected in the fact that 16% of the group randomized to surgery ultimately didn’t have surgery. The repair rate in EVEREST II is substantially higher than that reported in the STS database, but one must also consider that some patients referred for surgery undergo mitral replacement rather than repair.

Lange and Hillis: Patients with residual severe MR after percutaneous repair who successfully underwent MV surgery were counted as having had a successful outcome. Most clinicians would consider the outcome “clinically successful” when device deployment is accomplished without a major complication (death, MI, or cerebrovascular accident) and follow-up reveals no or only mild MR. By this definition, how often is percutaneous repair of MR clinically successful?

Feldman: Adverse safety events were less common with the MitraClip than with surgery, and major complications such as death, CVA, and need for urgent surgery occurred in MitraClip patients almost exclusively when they had later elective surgery. We examined several measures of clinical success. Surgery resulted in greater reductions in MR. Both groups had improved LV-chamber dimensions at 1 and 2 years, and NYHA class was better for MitraClip patients at both junctures. Not needing surgery (almost 80% of cases), feeling well, and improved LV function at 2 years may reflect “clinical success” from a patient perspective.

Lange and Hillis: The safety of percutaneous treatment is touted as superior to that of MV surgery, but transfusions were the largest single component of the major adverse events in EVEREST II. After transfusions were excluded, the rate of adverse events was statistically similar in the two groups. Did transfusions have an important effect on late outcomes?

Feldman: The impact of transfusions on outcomes has been the subject of much discussion. Numerous studies in the surgical literature demonstrate a clear acute and late effect of transfusions on mortality, compared with mortality in nontransfused cardiac surgery patients (e.g., Circulation 2007; 116:2544). The mortality risk has been shown to correlate with the number of units of transfused blood. Both adjusted and unadjusted analyses reveal a relative risk for mortality of at least 1.7 for transfused patients after cardiac surgery. I think it is fair to conclude, as we have seen after PCI, that transfusions contribute to adverse outcomes after cardiac surgery.

Lange and Hillis: Of the surgical group, 86% underwent MV repair. Of patients in the percutaneous-repair group who had severe residual MR and were referred for surgery, nearly half underwent MV replacement. Does percutaneous repair affect the patient’s eligibility for MV repair? How about after 3 or 4 years have passed?

Feldman: Surgical repair has been accomplished successfully after MitraClip therapy as late as 5 years after clip implantation. In a multivariate analysis of data from EVEREST II — presented by our surgical PI, Don Glower, at TCT — complex leaflet pathology (bileaflet/anterior flail) independently predicted the need for MV replacement, regardless of whether surgery was the first therapy or was performed after MitraClip implantation. Surgeon experience and duration of implant did not appear to affect the repair/replacement rate. Nor did the repair rate differ between patients who had an operative note of valve injury or difficulty removing the device and patients who did not have the operative note. Our experience has shown that MV surgery can be performed safely following the MitraClip procedure, with results similar to the control group at both 30 days and 1 year.

April 7th, 2011

Flying Back Home: Reflections on ACC.11

Hansie Mathelier, MD

Several Cardiology Fellows who are attending ACC.11 this week are blogging together on CardioExchange. The Fellows include Sandeep Mangalmurti, Hansie Mathelier, John Ryan (moderating and providing an outsider’s view from Chicago), Amit Shah, and Justin Vader. See the previous post in this series, and check back often to learn about the biggest buzz in New Orleans.

As I am flying back from another great conference, I start to compare ACC.11 (New Orleans) with ACC.10 (Atlanta). By coincidence, my first leg of the flight home is New Orleans to Atlanta. I had two very different but wonderful experiences. I think it was my approach to this conference. I knew I couldn’t see everything but I really wanted to… To solve this internal conflict, I purchased the ISCIENCE from the conference. The challenge now is going to be actually sitting down at home and watching these lectures. My goal will be to watch most of them by the end of April, but perhaps May would be a more realistic goal. This time next year, I will hopefully have accomplished my goal and will be ready to conquer another ACC.12 in Chicago.

Each day of the conference gave me new insights into my surroundings and my knowledge in the world of cardiology. I was able to conclude the conference Tuesday afternoon with a Fellows Bowl: a quiz bowl competition consisting of three teams — UCSF, PENN, and local team Tulane. A few of my collegues and I booked later flights in order to cheer on our co-fellows. There was audience participation with the key pads. In the end, the home team won and the rest of us walked away with examples of board review questions. A few of us were thinking this would be a terrific thing to do on a weekly basis back at our home institution as a great review of general cardiology.

My Top Eight

Concluding my conference experience, ala David Letterman’s Top Ten, my “Top Eight Things that I learned at ACC.11” (I think Letterman has Top Ten copyrighted) are the following:

8. PARTNER: “A good alternative to surgery.” Having managed patients pre- and post-TAVI, the next few years will be interesting as new questions will come up. How do you manage people after TAVI? Will the outcomes be the same as new centers start TAVI programs?

7. Cobblestones and uneven pavement are not my friends. Walking around ACC with a sprained ankle isn’t fun. Also, I quickly realized how long the conference hall is.

6. STICH: Medicine works!!!

5. The 5Ps: Plavix, PPI, Pharmodynamics, Pharmokinetics…after an afternoon section, might be easier to chose Prasgruel. If I needed a stent and was not sure if I am a nonresponder, which drug would I choose?

4. Networking and socializing with co-fellows, friends from residency, and meeting new colleagues and mentors through different events — priceless.

3. ISCIENCE: an easy way to hopefully conquer the conference at home.

2. Heart Hub: excellent way to maximize your conference. Very similar to watching three TV shows at the same time.

1. Spending time with co-fellows and attendings at a local restaurant sharing everyone’s experience about current and past conferences.

For more of our ACC.11 coverage of late-breaking clinical trials, interviews with the authors of the most important research, and blogs from our fellows on the most interesting presentations at the meeting, check out our Coverage Roundup.

April 7th, 2011

STICH: What’s the Value of CABG in Patients with LV Dysfunction?

Eric Jose Velazquez, MD

CardioExchange welcomes Eric J. Velazquez, an investigator for the STICH (Surgical Treatment for Ischemic Heart Failure) trial, results of which were recently published in two articles in the New England Journal of Medicine. Dr. Velazquez is the lead author of the STICH article that focuses on the clinical value of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) in patients with left-ventricular dysfunction. Dr. Velazquez answers questions about the trial from CardioExchange’s Dr. Anju Nohria. We welcome you to offer your own questions and opinions.

Background: In the STICH trial, 1212 patients with an LV ejection fraction ≤35% and coronary artery disease amenable to CABG were randomized to undergo either medical therapy alone or medical therapy plus CABG. According to an intention-to-treat analysis, the primary outcome of all-cause mortality (median follow-up, 56 months) was nonsignificantly lower in the group that underwent CABG than in the group that did not (36% vs. 41%; P=0.12). However, the advantage of CABG did reach statistical significance with respect to the rate of death from an adjudicated cardiovascular cause (28% vs. 33%; P=0.05) and death from any cause or hospitalization for a cardiovascular cause (58% vs. 68%; P<0.001).

In a substudy of 601 STICH participants, viability of myocardium was assessed with single-photo-emission computed tomography (SPECT), dobutamine echocardiography, or both. The mortality rate was significantly lower among patients with viable myocardium than among those without viable myocardium (37% vs. 51%; P=0.003), although that difference became nonsignificant after adjustment for other baseline variables (P=0.21). For mortality, no interaction was found between myocardium-viability status and either CABG or medical therapy.

Dr. Nohria: As you note in your discussion, the intention-to-treat analysis did not show an all-cause mortality difference between the two groups, but the per-treatment analysis showed an advantage of medical therapy plus CABG. You acknowledge that the imbalance in the crossover rates between the 2 groups may have diminished the evidence of efficacy from CABG in the intention-to-treat analysis. Given that, do you consider STICH a negative trial?

Dr. Velazquez: No trial is “negative” if patients and physicians win by having access to truly new data to inform complex decision making. The totality of the information — i.e., the adjusted analyses of the as-randomized (intention-to-treat population) for the all-cause mortality endpoint, the unadjusted and adjusted analyses of the important secondary endpoints, and the treatment-received and per-protocol analyses of all the endpoints — clearly supports the clinical efficacy of CABG plus medical therapy over that of medical therapy alone. My fellow investigators and I hypothesized that CABG plus medical therapy would reduce unadjusted all-cause mortality by 25%; instead, the hazard ratio in the CABG group was 0.86 (relative risk reduction, 14%; P=0.12). So from a purely statistical perspective, our finding did not prove our hypothesis; what we may infer clinically from the data is a different thing.

Nohria: How do the STICH findings influence your own clinical decision making about medical therapy versus CABG in patients with coronary artery disease and LV dysfunction?

Velazquez: This is in many ways the perfect finding for clinicians: It is nuanced, but so is clinical care and life. The STICH results reinforce for me the absolutely critical need for all of us as clinicians to spend time talking to one another and, more important, to patients, so that we can better understand their wishes and inform them about the risks and benefits of treatment choices. Neither medical therapy alone nor CABG is a magic pill or procedure. Medical therapy is effective, but with a 40% mortality rate at 5 years, it is not a cure and requires frequent reassessment. Patients and physicians do not need to rush the decision for CABG. If after careful review, however, there is a decision to take an up-front risk, I believe there will be a modest but clinically meaningful chance of improving long-term survival.

Nohria: Patients in the CABG group had a higher all-cause mortality rate in the first 2 years, particularly in the first 30 days, compared with patients who received medical therapy alone. In the STICH database, did you identify any patient characteristics (e.g., LV end-diastolic diameter, renal function, etc.) that predict a greater likelihood of early mortality after surgery?

Velazquez: Great question. Stay tuned, as much more is to come as we analyze what is a superbly rich database.

Nohria: Do you believe that myocardial viability testing has little value in helping clinicians decide who might benefit from surgery? Or do you think that other modalities such as PET or MRI may be more helpful than SPECT and dobutamine echo?

Velazquez: These data tell me that viability testing, regardless of the results, should not exclude patients from CABG. In fact, the data point to an early suggestion that the patients who may benefit the most from CABG are those without myocardial viability, turning the paradigm on its head. I have always said that functional recovery (of LV ejection fraction) does not necessarily equate with improved outcomes, no matter how much we wish it were so. We have seen that for decades with medical-therapy trials, going back to V-HeFT II. Regarding modality of testing, to alter the interpretation of the results, cardiac MRI and PET would have to be dramatically more sensitive for viability, and the results of that increased sensitivity would need to be completely independent of other more easily measurable and readily available clinical and imaging data. That has never been shown to be the case for clinical (not functional) outcomes.

Nohria: What percentage of patients in each treatment arm had cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillators (CRT-Ds) or implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs)?

Velazquez: The initial percentage of patients with ICDs was about 2% in each arm; that eventually rose to 19% in the medical therapy arm and 14% in the CABG arm. CRT-D use was 5% by the end of the trial. The slight imbalance in ICD use may have biased the results against CABG, but we have not analyzed that carefully yet.

Nohria: To assess whether CABG resulted in positive remodeling, did you analyze any follow-up LV ejection fraction or LVEDD data before and after surgery?

Velazquez: Stay tuned.

For more of our ACC.11 coverage of late-breaking clinical trials, interviews with the authors of the most important research, and blogs from our fellows on the most interesting presentations at the meeting, check out our Coverage Roundup.

April 6th, 2011

Large Study Finds Wide Differences in Risks Among Diabetes Drugs

Larry Husten, PHD

A very large observational study has found an increase in death and cardiovascular risk in people taking insulin secretagogues (ISs) compared with those taking metformin. Tina Ken Schramm and colleagues, reporting in the European Heart Journal, analyzed data from the entire population of Denmark and identified 107,806 people who initiated therapy with an IS or metformin. The study, they say, is the first “to analyse major cardiovascular endpoints with all currently approved ISs monotherapies in a nationwide setting.”

The analysis found a consistent increase in deaths and cardiovascular events associated with the most commonly used ISs, including glimepiride, glibenclamide, glipizide, and tolbutamide, while the risks associated with gliclazide and repaglinide were not significant.

Here are the hazard ratios and confidence intervals for mortality for the following drugs, compared with metformin, in patients without a history of MI:

- glimepiride: 1.32 (1.24–1.40)

- glibenclamide: 1.19 (1.11–1.28)

- glipizide: 1.27 (1.17–1.38)

- tolbutamide: 1.28 (1.17–1.39)

Here are the risks for mortality for the following drugs in patients with previous MI:

- glimepiride: 1.30 (1.11–1.44)

- glibenclamide: 1.47 (1.22–1.76)

- glipizide: 1.53 (1.23–1.89)

- tolbutamide: 1.47 (1.17–1.84)

In an accompanying editorial, Odette Gore and Darren McGuire write that the study is “among the most robust” due to its size, thereby giving it enough power to evaluate the individual agents studied. They warn against interpreting the study to mean that the drugs may cause harm, especially since metformin has been associated with an approximately 40% risk reduction for cardiovascular events and death compared with placebo.

Further, they write, an “important and novel finding of the present study is the variability of the estimates of hazard associated with individual insulin secretagogues, suggesting that some may be better than others with regard to the outcomes assessed.” In the absence of trial data, drug choices “remain grounded primarily on clinical judgement.”

“Ideally,” they conclude, “all drugs used to treat T2DM should undergo CV efficacy and safety evaluation, but for drugs that are already approved, and especially for those that are generic, it remains to be determined where the responsibility will fall to support such large and expensive clinical trial evaluations.”

April 6th, 2011

ACC Will Eliminate Current Model of Satellite Symposia at Future Meetings

Larry Husten, PHD

The ACC announced yesterday that it plans to eliminate the current model of satellite symposia at future meetings. The decision “was prompted in part by ongoing concerns about real and/or perceived bias in interactions with industry, specifically related to non-independence of certified satellite symposia.”

The ACC has not worked out the details of the new plan, but mentioned two broad changes:

- First, the ACC will integrate “a limited number of ACC-developed CME-/CE-certified ‘in-depth focused sessions’ into the overall ACC/i2 Scientific Session planning framework. These in-depth focused sessions will be planned and developed by the Annual Scientific Session planning committees as enhanced options to the structured sessions.”

- Second, the ACC’s Business Development Division will manage non-certified satellite symposia sponsored by industry.

“This move is important because it will allow for transparency in the two separate approaches and meet the educational needs of our members,” said Rick Nishimura, co-chair of the 2012 ACC’s Annual Scientific Session, in an ACC press release.

For more of our ACC.11 coverage of late-breaking clinical trials, interviews with the authors of the most important research, and blogs from our fellows on the most interesting presentations at the meeting, check out our Coverage Roundup.

April 6th, 2011

Getting “Under the Skin” of Resistant Hypertension

Amit Shah, MD, MSCR

Several Cardiology Fellows who are attending ACC.11 this week are blogging together on CardioExchange. The Fellows include Sandeep Mangalmurti, Hansie Mathelier, John Ryan (moderating and providing an outsider’s view from Chicago), Amit Shah, and Justin Vader. See the previous post in this series, and check back often to learn about the biggest buzz in New Orleans.

Treatment-resistant high blood pressure — what to do? It can be frustrating for both patients and clinicians alike, but perhaps there is hope. Today I learned about a cutting-edge treatment in the pipeline: Baroreceptor Activation Therapy, or BAT (see a recent open-access review here). It was discussed as part of the Rheos Pivotal Trial.

Similar to pacemakers and defibrillators, patients with resistant hypertension may eventually have the opportunity to implant this BAT device (the size of a first-generation iPod) under their right clavicle. It works by modulating the autonomic nervous system through baroreceptor reflex stimulation. It may also have downstream vascular and volume effects…

In the trial, which was a multicenter randomized trial of 322 patients, the efficacy and safety of this therapy was evaluated over the course of 1 year. I thought the findings were very interesting and thought-provoking. Some key points:

- With therapy, approximately 50% of patients achieved the goal of BP <140/90; LV mass index also decreased about 15%

- About a quarter of patients experienced a side effect related to the surgery (performed by a vascular surgeon). Of these, about a quarter were not reversible (e.g., permanent nerve damage)

- Even when the device was initially implanted, but not actually turned on, over 40% patients improved and nearly a quarter reached goal blood pressure by six months

The technology is improving as better, smaller devices are developed, and I’m sure complications will eventually drop; nonetheless, any type of surgery is daunting and has potentially fatal risks. All the same, so is the prospect of having a blood pressure of 180/100 despite five medications!

Other complementary therapies also take advantage of the baroreceptor reflex to lower blood pressure, such as acupuncture and yoga. Some holistic practitioners that I know recommend (and swear by) headstands for antihypertensive treatment. Of course, one may break his/her neck in the process! Needless to say, we have much to learn, and the investigation of BAT may provide some valuable insight into the pathophysiology of resistant hypertension, even if it ultimately does not become mainstream.

The limitations and surprising findings raise questions. Were the “resistant” patients actually taking all 3 to 7 medications they were prescribed? Nonadherence is a common reason for “resistant” hypertension. Were the patients (especially those who did not respond to therapy) ruled out for secondary and treatable causes? How did so many people benefit in the arm where the device was implanted, but not turned on? Ultimately, what is the future of such a therapy? Could make for a good discussion; feel free to share your thoughts!

For more of our ACC.11 coverage of late-breaking clinical trials, interviews with the authors of the most important research, and blogs from our fellows on the most interesting presentations at the meeting, check out our Coverage Roundup.