September 6th, 2012

Selections from Richard Lehman’s Literature Review: September 6th

Richard Lehman, BM, BCh, MRCGP

CardioExchange is pleased to reprint selections from Dr. Richard Lehman’s weekly journal review blog at BMJ.com. Selected summaries are relevant to our audience, but we encourage members to engage with the entire blog.

NEJM 30 Aug 2012 Vol 367

Aspirin Plus Clopidogrel in Patients with Recent Lacunar Stroke (pg. 817): Aspirin is an annoyingly good drug, which may have made Bayer’s fortune over a century ago but makes nobody much money now. Nonetheless, drug companies continue to seek for a marketable antiplatelet drug to replace or complement aspirin, and clopidogrel has been a very nice little earner during the period of its patent. This trial sought to establish whether combining clopidogrel with aspirin would reduce recurrent stroke after recent lacunar stroke. The aspirin dose was set high at 325mg, and adding clopidogrel to this made no difference to stroke recurrence but did cause more intracranial haemorrhage and was associated with higher mortality.

Lancet 1 Sep 2012 Vol 380

Risk of Coronary Events in Patients with CKD or Diabetes (pg. 807): In my last two weekly reviews, I’ve railed against the use of the expression chronic kidney disease without further explanation of what is actually meant. This paper adds a new twist to the crime: it uses a cut off eGFR of less than 60 in some places, and an eGFR of 45 in others. It refers to 3 grades of proteinuria, and finds that only the top level is predictive; but elsewhere the authors freely use the word “proteinuria,” without specifying its precise meaning or its relationship to eGFR. Most annoyingly of all, the authors talk about CKD in terms of how it compares with type 2 diabetes as a risk for myocardial infarction, usually without adjustment for age. As a result, this analysis of data from the Alberta Kidney Disease Network and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003-06 manages to be exceedingly cumbrous while failing to convey any clear clinical message. It will no doubt be used by advocates of universal screening for CKD—ignoring the fact the mean age of the “at-risk” group here was 71, an age at which most people should have been taking statins for 20 years if they wish to reduce their odds of cardiovascular disease—irrespective of their kidney function, or indeed their blood sugar.

September 6th, 2012

Unrecognized MI: More Prevalent and Dangerous Than Previously Suspected

Larry Husten, PHD

Unrecognized myocardial infarction is more prevalent, and is associated with a worse prognosis, than may be generally understood, according to a new study published in JAMA.

Studying a community-dwelling elderly (67-93 years of age) population in Iceland, Erik Schelbert and colleagues used ECG and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) to detect unrecognized MI. CMR was more effective than ECG at detecting unrecognized MI. The study established that unrecognized MI was twice as prevalent as recognized MI:

- No MI: 74%

- Recognized: 10%

- Unrecognized MI by ECG: 5%

- Unrecognized MI by CMR: 17%

Diabetics were more likely to have unrecognized MI detected by CMR than by ECG. After 6.4 years of follow-up, mortality was higher in the recognized and unrecognized MI groups than in the group without MI:

- Recognized MI: 33% (CI 23% to 43%)

- Unrecognized MI: 28% (CI 21% to 35%)

- No MI: 17%, (CI 15% to 20%)

After adjustment for other factors, unrecognized MI by CMR, but not by ECG, significantly improved risk stratification for mortality. People with unrecognized MI by CMR were less likely than people with recognized MI to take cardiac drugs.

According to the authors, the large percentage of unrecognized MIs has not been understood in the past due to previous reliance on ECG data; thus “a significant public health burden” has not been fully appreciated.

September 5th, 2012

Databases and Decisions

Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, SM

The decision about whether to undergo elective ascending aorta and/or arch replacement is often challenging. For some patients the indication may be obvious, but many patients need to weigh the potential morbidity and even mortality associated with the surgery against the chances that they will experience an acute, life-threatening event. Patients need good information about the risks and the benefits.

The current issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology has a report from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons that reports the outcomes of 27,202 patients who underwent elective ascending aorta and/or arch replacement surgery. Such studies of can provide good information about the experience of patients who do choose surgery even as they cannot illuminate the benefits.

The study reported a mortality rate of 3.4%, which the authors describe as excellent. But what we are not told is how the rate varies across centers: Did all the hospitals have roughly similar rates or did mortality vary widely by institution? Ultimately, whether 3.4% mortality is “excellent” may depend on whether you are the surgeon or the patient. We are not given information about whether it is as low as it could be. Finally, this study shows that major morbidity is much more common than mortality: stroke or coma occurred in 3.2% of patients, renal failure in 4.4%, pneumonia in 4.1%, reoperation for bleeding in 5.7%, and prolonged ventilation in 16.2%. The risk seems considerable for an elective procedure.

This study does provide critical information about contemporary practice. I wonder how this information will be incorporated into shared decision-making practices across the Society for Thoracic Surgeons sites. And will the risk estimates be tailored for patients and for the site?

September 4th, 2012

Danish Survey Finds Clopidogrel Less Effective in Diabetics

Larry Husten, PHD

A large nationwide survey of MI survivors in Denmark provides new information about the efficacy of antiplatelet therapy with clopdiogrel in patients with diabetes. In a paper published in JAMA, Charlotte Andersson reports on 58,851 MI patients, 12% of whom had diabetes and 60% of whom received clopidogrel.

As expected, diabetics had a worse outcome than nondiabetics: the composite endpoint of recurrent MI and all-cause mortality occurred in 25% of diabetics compared with 15% of nondiabetics. Overall mortality was 17% in the diabetic group compared with 10% in the nondiabetic group.

Clopidogrel was less effective in diabetics than in nondiabetics in reducing all-cause mortality and CV mortality:

- All-cause mortality risk reduction: 11% for diabetics versus 25% for nondiabetics (p value for interaction = 0.001)

- CV mortality risk reduction: 7% (nonsignificant) for diabetics versus 23% for nondiabetics (p value for interaction = o.01)

The results lend support to the hypothesis that “there may be a difference of effect of clopidogrel among those with diabetes compared with those without it,” write the authors. After acknowledging that “use of clopidogrel may still translate into a significant reduction in event rates for patients with diabetes,” they then raise the “possibility that patients with diabetes may benefit from a more potent platelet inhibitor strategy to achieve a relative risk reduction similar to patients without diabetes.”

In an accompanying editorial, Deepak Bhatt lends support to their suggestion, writing that it is plausible to suspect that there is “something about patients with diabetes that makes them less likely to respond to standard antiplatelet therapy.” Compared with nondiabetics, diabetics with coronary artery disease have increased platelet reactivity. Bhatt writes that the newer and more potent antiplatelet agents prasugrel and ticagrelor may be more effective in diabetics, although they may also increase the risk for bleeding, and they cost more than clopidogrel, which has now gone generic.

September 4th, 2012

CDC: Nearly 36 Million Americans Have Uncontrolled Hypertension

Larry Husten, PHD

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, new data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) show:

- 30.4% of U.S. adults (an estimated 66.9 million people) have hypertension.

- Of those with hypertension, 53.5% have uncontrolled hypertension (about 35.8 million people).

- 39.4% with uncontrolled hypertension (about 14.1 million) are unaware that they have hypertension.

- 89.4% with uncontrolled hypertension have a “usual source of health care and insurance, representing a missed opportunity for hypertension control.”

The CDC authors conclude: “The findings in this report can be used to target populations and refine interventions to improve hypertension control. Improved hypertension control will require an expanded effort from patients, health-care providers, and health-care systems.”

September 4th, 2012

You Got the Criminal. But What About the Bystander?

Mark Dayer, MD PhD FRCP and James Fang, MD

A 70-year-old man arrives via emergency services with an acute inferior MI. Despite hypertension and hyperlipidemia, he is physically fit, not diabetic, and has normal renal function. A drug-eluting stent is placed in his dominant right coronary artery. At the time of primary angioplasty, bystander disease is detected at the LAD/D1 junction, involving both vessels. The D1 stenosis is as severe as the LAD stenosis (≈80%).

A dobutamine stress echocardiogram, performed as an outpatient about a month later, is clearly positive for ischemia in the LAD and diagonal territories, and the patient experiences some chest discomfort at peak stress. An exercise stress test is not performed. The patient is asymptomatic during activities of daily living and denies having any angina.

Questions:

1. Do you manage the patient medically?

2. Do you stent his LAD coronary artery?

3. Do you offer him a left-internal mammary artery bypass graft to his LAD?

Response:

September 10, 2012

Aggressive medical therapy with lipid management, beta-blockade, ACE inhibition, aspirin, and other antianginals, as well as cardiac rehabilitation, should be the cornerstone of this patient’s management. The COURAGE and BARI-2D trials support this practice as safe and effective.

However, in an “asymptomatic” patient, the issue of survival benefit becomes primary. Some suggest, on the basis of observational studies, that revascularization may be superior to optimal medical management if relief of the ischemic burden is substantial (e.g., 10%-20% of the myocardium). Furthermore, exercise-related parameters such as those included in the Duke treadmill score are also useful in assessing prognosis from the CAD burden. Therefore, an exercise stress test should be performed to better define the ischemic threshold, territory at risk, and any symptoms. If there are high-risk features of the exercise stress test, the patient should be offered revascularization as adjuvant therapy to achieve a mortality benefit.

Deciding between PCI versus CABG for bifurcation LAD disease is highly individualized and depends greatly on the expertise of the surgeon or interventionalist, the technical nature of the anatomy, the patient’s comorbidities, and patient and physician preferences. At our institution, the coronary anatomy would be reviewed by both surgeon and interventionalist as to their technical ability to treat the disease. Interventionalists routinely address complex bifurcation disease, but the spectrum of comfort and expertise can range widely.

The 2009 Appropriateness Use Criteria for Revascularization recommend revascularization either for advanced symptoms or a large ischemic burden, even in the absence of significant symptoms. However, many asymptomatic clinical scenarios when the ischemic burden is intermediate received uncertain recommendations for appropriateness, so clinical judgment becomes paramount.

The ISCHEMIA trial will, hopefully, further clarify the role of revascularization on the basis of noninvasive testing rather than after angiography is performed. Soberingly, many patients who go on to coronary angiography do not undergo a noninvasive assessment for ischemic heart disease.

Follow-Up:

September 14, 2012

I thank Dr. Fang and everyone else who contributed comments. This case provoked much debate at our institution. I offered the patient the three options (optimal medical therapy, PCI, or CABG) and explained the uncertainty of his case. We finally settled on PCI.

The patient underwent an uncomplicated PCI to the LAD with a 2.5-mm x 18-mm drug-eluting stent, post-dilated with a 2.75-mm balloon. The diagonal branch was wired, and using kissing balloons the ostial lesion was dilated with an acceptable result. The patient is well and undergoing cardiac rehabilitation.

Although no published data support this approach, and I am usually conservative, I felt uncomfortable leaving this lesion. I look forward to the results of the ISCHEMIA trial, which I hope will clarify the issue.

September 4th, 2012

ESC Trials: The Best And The Worst

Larry Husten, PHD

Two trials presented at the ESC this year — WOEST and IABP-SHOCK II — are great examples of the way medicine is supposed to work. Another trial, FAME 2, is an example of so many of the things that can go wrong.

WOEST and IABP-SHOCK II

WOEST and IABP-SHOCK II are remarkably similar. Both trials tested conventional wisdom and found it lacking. WOEST examined the routine use of aspirin in “triple therapy”, which is when people already taking an anticoagulant undergo PCI and then receive an additional antiplatelet drug and aspirin. IABP-SHOCK II tested the routine use of circulatory support with intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation (IABP) for patients in cardiogenic shock following MI for whom early revascularization is planned.

Despite scant evidence, both of the ideas tested in these trials had received class 1 recommendations in the guidelines and were widely used in clinical practice. And both trials provided near definitive proof that the conventional wisdom was completely and utterly wrong.

This is the way science is supposed to work: an idea gets put to a fair test. Judging from the initial response to these trials, it seems likely that the cardiology community will rapidly accept the findings, and guidelines and clinical practice likely will change in short order to reflect the new evidence base.

FAME 2

FAME 2 also addressed, or claimed to address, an important question. Although the evidence base for PCI in stable angina had always been weak or nonexistent, its popularity had undergone exponential growth for many years, until COURAGE famously put the brakes on this growth. When fractional flow reserve (FFR) first came along, it was viewed with considerable suspicion in the interventional community, since in many respects it helped confirm the findings of COURAGE by appearing to demonstrate that a significant percentage of lesions intervened upon were not ischemic and therefore almost certainly didn’t benefit the patients who had undergone PCI.

Eventually, however, the interventional cardiology community found a path to renewal with FFR. Perhaps, it reasoned, instead of being used to illustrate the lack of utility of PCI, FFR could be used to guide PCI decisions, limiting interventions to ischemic lesions that would benefit from PCI.

This is where FAME 2 comes into the picture. In the trial, patients who had at least one functionally significant lesion, as defined by FFR, were randomized to FFR-guided PCI plus medical therapy or medical therapy alone. The trial was stopped early, after only about half of the intended number of patients were enrolled, because of a significant reduction in the primary endpoint (the composite of death, MI, or urgent revascularization) in the PCI group compared to the medical- therapy-alone group.

The FAME 2 investigators, along with many members of the interventional cardiology community, have presented the results of the trial as a definitive response to the questions about PCI raised by COURAGE. In an ESC press release, FAME 2 coordinator Bernard De Bruyne said:

“With this new knowledge, I believe that FFR should become the standard of care for treating most patients with stable coronary artery disease and significant coronary narrowings.”

The Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) was so excited about the results of FAME 2 that it rushed out an e-publication of a “President’s Page” perspective on FAME 2, written by SCAI president J. Jeffrey Marshall and interventional cardiologist Ajay Kirtane, arguing that “FAME 2 offers the best data currently available to guide” treatment. The perspective of most interventional cardiologists is probably best summarized by this headline published on TCTMD: “PCI Bests Medical Therapy in Stable Patients with Proven Ischemia.”

The sad thing about these simplistic responses to FAME 2 — and the reason why I use this trial as an example of a poor model for clinical trials — is that there is no acknowledgement of the extraordinary division of opinion about this trial and its meaning. The SCAI document discusses the FAME 2 publication but does not even reference, or respond to, the issues raised in an editorial accompanying the publication of FAME 2 in the New England Journal of Medicine. That editorial, by Bill Boden, the principal investigator of the COURAGE trial, delivered a trenchant attack on the view that FAME 2 represents anything like a definitive response to COURAGE.

I summarized Boden’s points in my previous news story about FAME 2:

- There were few “hard” events in FAME 2 and urgent revascularization could be performed without objective evidence of ischemia or positive biomarkers.

- Since the trial was unblinded, “investigators may have had a lower threshold for recommending revascularization” for patients in the medical group.

- Patients in the FFR group did not have noninvasive testing demonstrating ischemia, so some may have had preserved myocardial perfusion.

- Patients in FAME II were not at very high risk.

- The short followup period (mean followup of 7 months) did not leave enough time for the risk of restenosis in the PCI group to fully emerge.

Boden is highly critical of the early termination of the study, writing that it leaves “more questions than answers… but the only enduring finding of the FAME 2 trial appears to be that of a reduced short-term rate of unplanned revascularization with FFR-guided PCI, with little evidence of long-term, incremental benefit on prognostically important clinical outcomes.”

Astonishingly, the ESC press release didn’t even mention that the ESC’s own discussant of the trial, Frans Van de Werf, concluded that FAME 2 did not provide the “final answer to the question how to treat stable CHD patients.” Here on CardioExchange, Rick Lange and David Hillis provided another deeply skeptical perspective on FAME 2, and their view received endorsements from Sanjay Kaul, David Cohen, and Harlan Krumholz.

PCI supporters are acting as if the new evidence provided by FAME 2 forges a new consensus in support of FFR-guided PCI, but only by ignoring a chorus of dissent.

It is perhaps worth noting here that WOEST and IABP-SHOCK II were investigator-driven trials in which industry played no significant role. Of course, this idyllic situation may have been possible only because no significant commercial interests were at stake in the trial. With FAME 2, by contrast, the commercial stakes — for industry, for hospitals, and for interventional cardiologists — could not be higher. Perhaps these influences have helped induce a self-interested reality distortion field.

September 4th, 2012

FDA Warns Against Using Revatio in Kids with Pulmonary Hypertension

Revatio (sildenafil) should not be prescribed to children and adolescents with pulmonary arterial hypertension, according to an FDA MedWatch alert.

The warning is based on the results of a trial published in Circulation that showed increased mortality at medium and high doses of Revatio, compared with low-dose treatment, among patients aged 1 to 17 years. Low-dose Revatio did not improve exercise capacity.

The FDA notes that Revatio has never been approved to treat pulmonary arterial hypertension in children.

Reprinted with permission from Physician’s First Watch

August 30th, 2012

ICD Investigation: DOJ Sends Resolution Model to Hospitals

Larry Husten, PHD

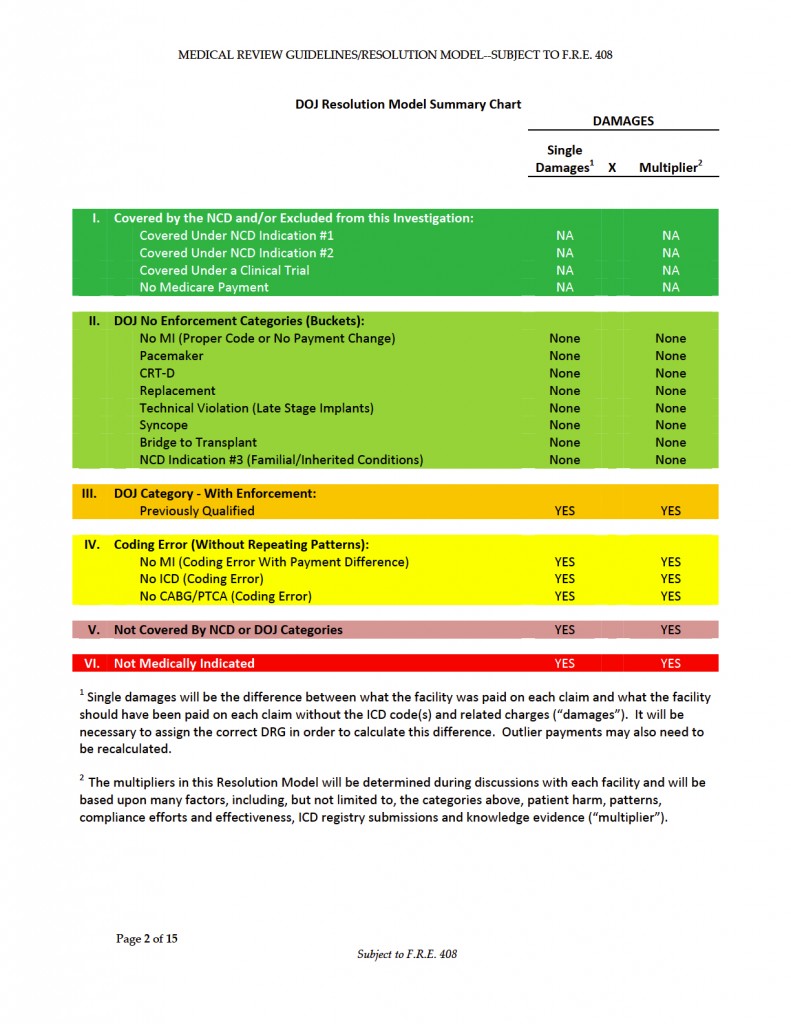

Hospitals across the country received emails from the U.S. Department of Justice on Thursday containing a proposed “Resolution Model” that will allow the hospitals to begin to settle the long-standing and much-feared DOJ investigation into improper Medicare billing for ICDs. The action appears to confirm an article, published earlier in August in Report on Medicare Compliance, that summarized the key details of the novel program.

As reported by ModernHealthcare.com (free registration), the document sent to hospitals contains “instructions to examine questionable implantable defibrillator surgeries on Medicare patients and estimate potential penalties under the False Claims Act.” Some hospitals, according to the story, “have been asked to provide information of hundreds of cases each.”

Hospitals are being asked to perform audits on their cases and to estimate damages, “with the severity of penalties based on whether the hospital had medical reasons to violate CMS rules; if patient harm resulted; if the hospital had prior knowledge or a statistical pattern of non-guideline implants; and if a hospital compliance program was in place.”

Here is the DOJ Resolution Model Summary Chart:

August 30th, 2012

Was That an MI or Not? The Stuff of Controversy

Stewart Mann, DM (Oxon), FRCP(UK), FRACP

The word infarct derives from the latin infarcire, meaning “to stuff”, and was applied to myocardial damage when histologists noted the hypercellularity of the affected area of myocardium. I doubt whether the physicians of the day would venture to tell the patient their heart was “stuffed”, which is presumably a later use of the word, but not necessarily inapplicable. However, we have come a long way from that description and the advent of ever more sensitive biomarkers means that many events we now classify as myocardial infarction (MI) would probably not show this histological change.

In many cases, we have no difficulty deciding whether an MI has taken place but, as a one-time outcomes assessor for a large multicenter trial, I am only too aware that there are many clinical presentations where the diagnosis is contentious. The importance can be critical — for the social and personal circumstances of the patient, the consequent decisions for clinical management, and the results of clinical trials. I attended three sessions at the ESC that focused on the outcome of deliberations of the international task force that developed the third version of the Universal Definition of MI, now published in no fewer than five journals simultaneously. There was plenty to debate.

Two examples that divided the committee were that of a 14-year old with a prolonged episode of supraventricular tachycardia with chest discomfort and a small but qualifying biomarker rise, and an endurance athlete with similar findings.

The emergence of the concept of a “Type-2 MI” in the last iteration of the universal definition (2007) has been useful in restraining cardiologists (and those who would refer to them) from initiating the now default practice of rushing in with treatment appropriate for a “Type-1 MI” (due to plaque rupture) when this is unlikely to have been the pathology. However, during the discussions a number of verbal knots and conceptual gymnastics ensued when trying to differentiate Type-2 MI and myocardial injury. We in the audience were left a little unsure as to whether the latter included the former or if it was a separate category qualified by the term “not due to ischemia.” It was also a moot point whether, in the two patient examples, ischemia could be confidently ruled in or out. When all was said and done, we were exhorted to resort to that crucial but arbitrary deal-breaker of careful clinical judgement.

Another point of contention and change to the previous definition was how much leeway interventionalists may have in not classifying post-procedural rises in troponin as MIs, especially as newer, highly sensitive troponin tests have lowered the values detectable. The new threshold is 5 times the upper limit of normal and supporting evidence was provided that such rises were not of prognostic importance. Surgeons get 10 times the upper limit of normal and at least one audience member wondered if these multipliers weren’t a bit arbitrary.

Among other issues debated was the importance of using a “delta”, or change in levels, as the crucial leverage point for an MI classification, but task-force member Alan Jaffe helpfully (?) pointed out that each troponin assay is different and timing of samples must be standardized for valid comparison. The task force has yet to reach consensus on what the delta needs to be — absolute or percentage change, universal statistic, or different ones at different absolute levels of troponin.

So there’s plenty of “stuff” to keep researchers busy, cardiologists scratching their heads, and the task force in business until version four of the Universal Definition of MI comes around.