May 13th, 2014

The Effect of Incarceration on the Epidemiology of Heart Disease

Emily Wang, MD, MAS

Emily Wang is an Assistant Professor at the Yale School of Medicine and Co-Founder of the Transitions Clinic Network, a consortium of 11 community health centers nationwide dedicated to caring for recently released prisoners and defining best practices for the health care of individuals leaving prison.

The United States incarcerates more people than any nation in the world, with currently 2.2 million individuals behind bars. Rates are the highest among African-American men, who have a one-in-three lifetime chance of being incarcerated. What does this have to do with cardiology? It turns out — more than you might think.

Aside from the fact that former prisoners have higher rates of hypertension, diabetes, and hospitalizations and deaths from cardiovascular disease (even after controlling for sociodemographic variables), the disproportionate incarceration of minority men may stymy the epidemiology of heart disease.

In 1978 the federal government restricted research on prison and jail inmates in medical studies, which was the result of decades of unethical research in correctional institutions. Currently, government regulations bar study subjects from participating once they are incarcerated, unless the study investigators apply for special permission through their institutional review board. If studies do not specify otherwise, community-recruited participants who enroll in studies cannot be followed while they are incarcerated. In certain jurisdictions, they cannot be followed after their release.

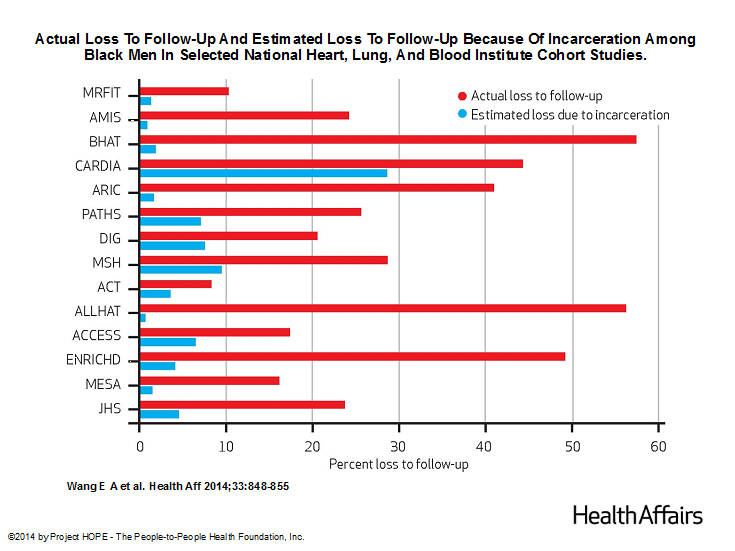

Because individuals who are already in ongoing studies must be dropped if they are incarcerated, this may compromise studies of health outcomes in minority populations, particularly studies involving black men, who are disproportionately incarcerated. In a study published in this month’s Health Affairs, we explored the effect of incarceration on follow-up rates of 14 prospective clinical studies funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). We chose to examine NHLBI cohort studies because it is the only institute that systematically requires the submission of all protocols and data for public use after trial completion.

We estimated that, during the past three decades, high rates of incarceration of black men have accounted for up to 65% of the loss to follow-up among black men in these studies.

The impact of incarceration was far less among white men, black women, and white women. These estimates suggest that the ability of those studies to examine racial disparities in health outcomes, as well as to understand the experience of this group, could be compromised. It becomes far more difficult for analysts to have access to a large number of cases so that they can draw statistically significant conclusions about cardiovascular disease, which is far more common among black men than white men, and is complicated by many factors that influence illness and death.

Under current circumstances, the results of longitudinal studies may fail to accurately represent the experience of black populations and may bias estimates of racial disparities by either excluding people in jail or prison or discontinuing longitudinal follow-up at the time of incarceration.

So what can be done? In 2006, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) convened a committee to explore “Ethical Consideration for Research Involving Prisoners.” The IOM suggested shifting from “a category based to a risk based approach to research review” [of protocols involving prisoners] and including a “framework” of “collaborative responsibility.” I think that this makes sense and that research subjects who consent in the community and then are incarcerated should be allowed to continue participating in observation research that poses minimal risk to research. But these changes have not been incorporated despite the IOM recommendation.

Perhaps the next step is to include patients in this conversation because of what is at stake: we know very little about the health risks of subjects during incarceration and that affects what we know about the health of black men in general.

Great article Dr. Wang. I am a cardiology fellow and also moonlight as an internist at our local county jail which houses several thousand inmates. I get to take care of all the cardiac patients. Though I completely agree that we don’t know the cardiac outcomes of those incarcerated, those results I think would surprise most.

My incarcerated patients are a very captive population. My heart failure patients get weighed daily/weekly. There meds are uptitrated and diuretics tracked. Patients with chronic angina have antianginals titrated, they are educated about their CAD and have less emergent ER visits from the jail which cost the county thousands. We have the ability to text/email EKG that can be obtained at anytime day or night. When they leave jail, they are given prescriptions for all their cardiac meds and referred to the local university program. It would be interesting as you mention to study this population and see what difference is being made.

Thank you for sharing your experiences. I agree that this would be a great study. The data from other chronic conditions are limited; studies of HIV indicate that patients’ CD4 counts and viral load are far better in prison/jails compared with when they are released. I would suspect that this is the case for patients with diabetes, hypertension, heart failure but no studies have been done. We have looked at rates of hospitalizations among Medicare beneficiaries post release compared with matched controls and found higher rates among returning prisoners for ambulatory care sensitive conditions, including diabetes, and hypertension, in the first 30 days following release: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23877707