September 20th, 2016

Academic Near Miss

Jamie Riches, DO

I began one of my PGY2 medical oncology rotations alongside my co-resident: an MD/PhD, fast-track (pre-matched into fellowship) future oncologist. Among my three interns that rotation, two were “Harvard kids.” Needless to say, I was intimidated. My colleague and counterpart not only had the entire catalogue of genomic alterations at the tip of his tongue, he knew and understood their implications on disease. I saw my intern having a long conversation with a nurse at our patient’s door, and when I approached to see if there was anything I could do, I observed him giving a flawless lecture on the approach to an abnormal urinalysis and what really necessitates antibiotic treatment. I wasn’t really sure what I could add to this equation.

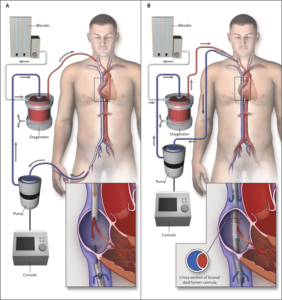

Over the course of the rotation, I found my place, and we all settled in to our roles. We learned from and taught each other different things. We had sick patients, and we took good care of them. When we felt like we’d exhausted all of our medical options to potentially reverse whatever underlying condition that we were attempting to treat, we would joke, “it’s time for ECMO.” When the joke began, I knew what ECMO was, but I didn’t really know how ECMO worked. I silently laughed along, certain that my co-resident and intern possessed superior understanding of this process and would lose all faith in my future contributions to the team should they become aware of my knowledge deficit. But, as we sat at the workstation one day, my co-resident opened Wikipedia and asked, “How does ECMO work exactly?” From there, the intern opened a series of diagrams and images, and we stood together, learning. I look at that experience as an academic “near miss.”

(If you’re curious about ECMO, read this.)

This experience is admittedly mundane, but it highlights one of the turning points in my career. I realized that, for years, I was embarrassed to read. The one piece of advice we’re given as trainees is “read more.” It is tattooed onto our physician-in-training souls. And I did read, but I had been reading “in private,” ashamed to admit that any knowledge deficit existed. I was convinced, each time I read, that I was looking something up that “I should already know.” And yet, there we sat for 5 minutes, looking up something in broad daylight!

I now know more about ways to learn. Working for 12 or 18 hours and attempting to absorb an article or chapter on the subway ride home is self-sabotage. “Spaced learning” is on the rise. Gone are the days of walking to the library to check out a stack of books. Medicine programs (such as my own), major journals, and academic societies “feed” you information via Twitter. We have infinite access to information in real time and limited time to access it. Despite our own aspirations for perfection, not having infinite knowledge is human. A piece of advice to interns and residents: Ask questions. Look up your own answers. Read more. Let what you don’t know motivate you. Being ashamed to acquire knowledge is a tragedy.

I now know more about ways to learn. Working for 12 or 18 hours and attempting to absorb an article or chapter on the subway ride home is self-sabotage. “Spaced learning” is on the rise. Gone are the days of walking to the library to check out a stack of books. Medicine programs (such as my own), major journals, and academic societies “feed” you information via Twitter. We have infinite access to information in real time and limited time to access it. Despite our own aspirations for perfection, not having infinite knowledge is human. A piece of advice to interns and residents: Ask questions. Look up your own answers. Read more. Let what you don’t know motivate you. Being ashamed to acquire knowledge is a tragedy.

I love reading these columns.

“Read more.” Yes, we should all do that. The fact that we are physicians means that we are already compulsive readers.

Reading more medical information might improve our technical practice of medicine. Might. What I suggest is that we choose to read more widely in a manner that will make us better physicians as humanists rather than technologists.

The hospital is an “ivory tower” of sorts. Read Dostoevsky (just an example) and learn more about life.

Thank you, Frank. Humanistic reading is a beautiful thing!

Thank you for sharing a fear that many in health care seem to have… That we all need to know everything… By memory! This is a falsehood. Healthcare today is all about using the evidence provided by research. The changes in best practice change at the speed of the Internet. In order to provide the most up to date, and safest care, we all need time to look things up. I have tried to do this since I was a new nurse and continue to try as an advanced practice nurse and educator of nursing students. You are right that, for some, they look at this as a weakness of some kind and are afraid to let others see them look things up. After 30 years in healthcare, I can tell you that the reason I trust my family physician so much is that he never hesitates to look something up… While in the exam room with me. I appreciate, and respect, his diligence in trying to provide the best care to me and my family. So… You keep on looking up and learning. Your patients are better for it!

Thank you Denise- I hope that when educators, such as yourself, accept that these fears need to be abolished and that good practice means gathering knowledge (not simply possessing inherent knowledge), trainees will be more comfortable.

Great article.

Thank you!

In Med Onc 37 years, look up new stuff every day. Uptodate, pubmed etc are magical though fares to knowledge. Calls to other practioners, consultants are all important factors in staying current.

Thank you, Dr. Hutchins.