February 4th, 2021

Engaging with History: Why Do the Actions of Nazi Physicians Matter in Medicine Today?

Holland Kaplan, MD

The reflections and photos in this post are a result of the immersive experience I had via the Fellowship at Auschwitz for the Study of Professional Ethics in 2016.

Many assume that Nazi physicians were antisocial, sadistic psychopaths. But viewing the perpetrators of the Holocaust as morally deficient is simply inaccurate; in fact, the Nazis physicians were often well-known, highly respected individuals at the tops of their fields. The Nazi philosophy was based on scientific and historical factors that developed over many years and culminated in the Holocaust. In the actions of Nazi physicians, we can see how many important principles in the practice of medicine were broken. Studying the actions of Nazi physicians reinforces that we may all be capable of violating these principles, and we must be constantly vigilant to maintain our compassionate, humanistic, ethical practice of medicine.

Enhancing patients’ right to healthcare

The Nazis had a warped view of “public health” that centered on “racial hygiene,” a concept that represented the evolution of ideas introduced in Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species. By 1920, the phrase “life unworthy of life” was commonplace in Germany in referring to terminally ill patients and psychiatric patients. When Nazi doctor Fritz Klein was asked how he was able to murder people after having taken the Hippocratic Oath, he responded, “Of course I am a doctor and I want to preserve life. And out of respect for human life, I would remove a gangrenous appendix from a diseased body. The Jew is the gangrenous appendix in the body of mankind.” The moment we believe that certain groups of people, whether elders, socioeconomically disadvantaged, incarcerated, disabled, or with whatever other trait we choose, are less worthy of healthcare is the moment we start to invalidate their humanity and their worthiness of life. The American healthcare system unfortunately often makes it difficult to ensure that all groups receive equitable healthcare. Thus, it is our job as physicians to advocate for our patients to the best of our ability at the individual, state, and national levels.

Informed consent is critical in clinical medicine and research

The Nazi doctors enacted a variety of non-consensual human experiments. These experiments included determining the “most effective” means of killing people (e.g., injections of phenol vs. starvation vs. gassing), freezing subjects to identify effective treatments for hypothermia, and bone grafting experiments to test the efficacy of newly developed medications. The purpose of many of these experiments was to identify efficient methods for killing people the Nazis deemed “undesirable” and to perform general basic science research in which a given Nazi doctor had a special interest. From post-war scrutiny of these experiments arose the Nuremberg Code, a set of guidelines that outlines principles of research ethics in human experimentation. From consent in research projects to day-to-day consent for medical procedures, it is critical that we ensure our patients are well-informed of the risks of the procedure to which they are consenting and that they are voluntarily agreeing to undergo the intervention.

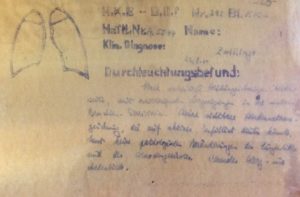

Description of the results of a lung x-ray within the experiments conducted on twin children by Dr. Joseph Mengele, photo taken at Auschwitz in June 2016

Importance of challenging the hierarchy

The sociological phenomenon of people’s willingness to follow orders also played a prominent role in the actions of the Nazi physicians. Stanley Milgram’s famous 1961 obedience experiment showed that people exhibit a chilling willingness to follow orders, particularly when there seems to be a greater cause and an authoritative figure giving orders. In his testimony in the Nuremberg Trials, defendant Dr. Karl Brandt was asked whether the ultimate responsibility for the medical crimes that took place in the Nazi concentration camps should fall on the state or on the physicians. Dr. Brandt responded, “In my view, this responsibility is taken away from the physician because the physician is merely an instrument. The feeling of a special professional, ethical obligation has to subordinate itself to the totalitarian nature of the war.” The dissemination of responsibility from an individual to a group of people can enable individuals to engage in unethical actions. Impenetrable hierarchies in medicine continue to exist to varying degrees, often differing between specialties and institutions. However, the idea that strict adherence to a hierarchy can negatively affect patient safety and patient care is commonly taught in medical schools. As a result, there are measures in place that intentionally disrupt the chain of authority in medical practice. For example, a patient’s nurse may be specifically sought out during a medical team’s rounds to ensure that any of his or her concerns are addressed. Formal avenues exist for medical students to lodge concerns regarding mistreatment of themselves or patients. Centers of professionalism and ethics abound in medical schools to address these types of violations.

Taking action against dehumanization and decreased empathy in medicine

In their participation in concentration camps, Nazi doctors were able to psychologically distance themselves from their actions by dehumanizing prisoners (e.g., using prisoner numbers instead of names, stripping people of their clothing and other belongings, viewing individuals as animals instead of people). In the modern practice of medicine, constant exposure to the pain and suffering of other people often has a numbing effect. Medical professionals may eventually become less susceptible to having an emotional response to another person in pain. It is a well-studied phenomenon that medical students become decreasingly empathic as their training progresses. This apathy towards pain and suffering that may develop over time in physicians is concerning, because it may enable a similar apathy when immoral actions occur. Those who commit evil do not necessarily have evil motives. This decreasing empathy and lack of self-awareness in the medical profession is a systemic problem that physicians should be aware of and which needs to be continually addressed. Some possible interventions, many of which are already occurring, are to include courses and activities in medical practice that enable reflection and empathy. Examples include patient memorial services, reflective writings, and facilitated small-group discussions on the role of empathy in medicine. Encouraging and enabling physicians to have other roles in their lives can also be helpful, as a person who functions as a physician, a mother, a wife, and an active community member has the opportunity to re-orient herself and look at her role as a physician from other perspectives.

Ultimately, every historical age has its own outlook and attempts to solve the problems it faces in unique ways; it is by studying how these historical problems arose and the results of their attempted solutions that we can start to have a basis for solving problems of our own time. By learning from the atrocities committed by Nazi physicians, we can hope to avoid similar actions in the future and hopefully better the practice of medicine.

References

Alexander L. Medical science under dictatorship. N Engl J Med 1949 Jul 14; 241:39. (https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM194907142410201)

Chen D et al. A cross-sectional measurement of medical student empathy. J Gen Intern Med 2007 Oct; 22:1434. (https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0298-x)

Lifton RJ. The Nazi doctors: Medical killing and the psychology of genocide. 1986. New York: Basic Books.

Milgram S. Behavioral study of obedience. J Abnorm Psychol 1963 Oct; 67:371. (https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040525)

I strongly disagree with the statement that we all could be like Nazis ( including yourself). If so , then anyone in the world could be . Not just physicians . The word Nazi these days is thrown about way too much, for political pleasure

Thanks for your comment! I do believe that anyone (not just physicians) has the capacity to commit evil acts if the circumstances predispose to it. And I think the frightening part is that people may not always be aware that their actions are immoral. I agree with your sentiment that the Nazi analogy (i.e. that we can slip into Nazi-level atrocities at a moment’s notice) is overused, and I don’t think we’re anywhere near it in the practice of medicine in the US. But I also think it’s important to learn from history.

Of course anyone can “become” a Nazi in the right circumstances. There is not a Nazi gene, although possibly there is a genetic make up for narcissistic authoritarian leaders. The majority of Germans did not suddenly become evil followers of Hitler during the Weimar Republic and then make an equally sudden transition to decent post war citizens. There is a Nazi Documentation museum in Munich that shows the early day by day steps that Hitler took over 5 years to instill distrust, fear, blame and finally hate on “non-conforming” Germans. Initially they are baby steps that are ignored but as they are not checked they grow bolder and bolder until hate finally becomes “normalized and commonsensical”. Nazism was modern, technically sophisticated, and happened in a democracy. It was also propagated in the name of Christianity. Its lessons are chilling. As our society moves to ever more specialized technical education that skips out on the subjects of history, sociology, political science, and the humanities, the power of disinformation and propaganda is always a threat. Witness the astounding popularity of Qanon even among engineers and computer scientists. As newspapers close and investigative journalists disappear this threat will become great indeed.

This is an excellent example of the need to separate government from our healthcare. As physicians, we are constantly encouraged by academia in the bureaucracy in Washington and are constantly forced to practice according to the guidelines of central planners in Washington and with in their insurance company crony offices. As government gets more and more involved in our healthcare, it is a small step for the government to continue to push an ideology that is foreign to the protection of the individual. In fact, we are already being forced to do this. Thus, If there are lessons to learn from fascism/Corporatism of the 20th century it is the government should be limited as originally intended in the constitution. As long as the government remains involved in our healthcare, not only will be inequities and economic dislocation continue to occur but human abuses under the guise of “quality”, “evidence-based medicine”, “complete lives system’ , ‘making good choices’, etc will morph into total control of the individual. The gulags of Solzhenitsyn and camps of Mengele will be right behind. Thus, in order to stop these potential human rights abuses, we must stop the cancer of collectivism/progressivism

it is not the government that is interfering with physicians caring for our patients. The govt is not involved at all when BCBS or Aetna denies your claim. it is the private insurance companies that are creating networks telling us which physicians we can see and where, it is the private insurance companies that are deciding whether care, decided on by physician and patient, will be covered. The govt is not at all involved in these decisions. With traditional Medicare, it’s clear what the benefit is and you can see any physician at any hospital in any state. It is the private insurance companies and the administrative burden that they have placed on physicians, the creation of hospital conglomerates making physicians nothing more than an employee while taking away their autonomy in deciding what patients need, and the lack of coverage that enables the huge profits of hospitals and insurance companies while not providing needed care. make sure you are angry at the correct enemy.

I think you have it backwards. Why would an “individual” feel safer in a corporate controlled for-profit medical system without regulations or democratic oversight? You lump academia in this basket? Perhaps medical training should self-taught? What are you saying here?

Medicine is not just about “individuals” making their own choices. It is is about research, disseminating that research, and putting that research into practice without the conflicts of interest that distort this process. In a world of specialized knowledge, individuals have to trust those certified to act in their best interest. It is a duty and responsibility of all professions and they must be accountable. It is obviously complex and difficult which means that everyone involved must continually strive to make ” the system” better. Being a professional isn’t just a career, it is always a work in process and involves improving the profession itself. Throwing your hands up when things don’t go your way and denouncing everyone else is probably the most useless thing you can do.

Adams and Balfour’s “Unmasking Administrative Evil” is a classic exploration of diffusion of moral responsibility that can occur in bureaucracies, even among otherwise ethical actors. It also highlights the courage required of whistle-blowers and the often-severe repercussions that befall them.

Dr Kaplan,

A very nice insightful blog which touches on issues we all have pondered. How and why did it happen, and to what degree are we at risk to repeat, albeit in a more sophisticated manner? Over 50% of physicians today are employed by an entity they do not and cannot own. The trend will see this percentage grow. Challenging hierarchy is likely to become more difficult and workloads of the employed more likely will lead to apathy and dehumanization as physicians lose autonomy and control of personal professional action. I see this to some degree now. Your blog speaks to some of the mechanisms to combat, but it would be helpful if you drilled a bit deeper.

Thanks again.

John C Bagwell, MD, FACP

Thank you for your comment, Dr. Bagwell! The factors you mentioned that contribute to emotional detachment and dehumanization are very concerning. I think step 1 is identifying and acknowledging the problem, and step 2 is working together to determine the best mechanisms to combat these phenomena. I certainly hope to continue to work on step 2 throughout my career.

I am a doctor. I know what does it mean to know a person by his/her illness, not by her bame.Itța badbut useful when you gave too many on your list. You remember the important cases by their names, but not all people. But even if you depersonalize them, you know they are beings.. they have feelings. In my oppinion the worst problem is that some human beeings like to follow orders and to follow one chief.

The gregarious spirit kills humanity in many people and explains war and hate .

Comparing negative facts and developments in todays medicine and its practice by medical professionals with NAZI ideologies and facts is absolutely not acceptable and puts the two on the same level and plays down NAZI atrocities.

Also I absolutely don’t agree that as you say “The Nazi philosophy was based on scientific and historical factors that developed over many years.” This sounds as if NAZI “philosophy” belongs to any other serious science.

It may be, Dr Kaplan, that your intentions were good, but please in the future choose some other item for trying to convey your idealistic ideas.

I agree 100%. Another example of tone-deaf virtue signaling.

“But viewing the perpetrators of the Holocaust as morally deficient is simply inaccurate”. With all due respect…as someone with DOZENS of great-uncles, great-aunts, 1st cousins once removed, and great-grandparents who were murdered by the Nazis (the actual ones, not just those American citizens with whom you don’t agree with politically), I think you need to reconsider your words.

Highly thoughtful, timely writing – especially as more, not less, dictatorial power becomes evident nationally and internationally, and racism is beginning to be more effectively addressed. Lessons learned – we need to be reminded. Thank you.

Dr. Kaplan’s words were well chosen. Please re-read her text.

There is nothing that should offend the descendants of the Holocaust.

No one group has a monopoly on 20th century genocidal suffering.

Her words do not need to be reconsidered.