January 13th, 2017

Ganbare

Jamie Riches, DO

“May I never see in the patient anything but a fellow creature in pain.”- The Oath of Maimonides

I am not immune to the post-election frenzy. Never in my relatively short life, nor in my even shorter existence on social media, have I seen people so divided. Shortly after the president-elect was named, I found myself wondering, “Are you one of us, or one of them?” I had to sit myself down and ask what that even means… I am no party loyalist. I am an American. I voted for a candidate who I thought represented my fundamental values, and against a candidate who has incited a furor with which my values do not align. It occurred to me that most Americans have made the same decision, with varied outcomes.

Spoiler alert: I didn’t vote for Donald Trump. I spent a good few days wondering how anyone could. I stayed quiet — a passive observer of Facebook and Twitter. I watched as documented hate crimes filled the news, as people’s relationships became publicly strained. I told my dad that I was “heartbroken” after the election, and he said, “Why? I couldn’t stand her.” He was one of them. We quickly changed the subject. My dad is probably considered an “uneducated white male,” when it comes to polling stats and media representation. My father doesn’t have a medical degree, or even a college degree, but he has a knowledge base and skill set that allowed him to perform a job that I am not capable of. He’s a retired New York City firefighter, along with his brothers, his nephews, and my mother’s cousins and their sons. He’s a smart guy. They all are. They’re good men. They do good work. I started to dissect the term “uneducated” and even become offended by it. I moved into a new apartment last week and hired a team of people to help me disassemble and move furniture. These were probably “uneducated” or “working class” people, who again were able to do a job that I simply could not. Their education, their training, is different from mine. Their electoral decisions may (or may not) have been different from mine. We are people. We are Americans. I am part us and part them.

As I frantically refreshed my Facebook feed, I continued to come across divisive language. The same people who think Matt Maloney has no right to ask his employees to resign if they disagree with his criticism of the president-elect think it’s OK to ask people to leave the country if they disagree with their religious views and vice versa. I thought about my own workplace and what it would mean to allow such discrimination (on either end of the political spectrum) to prevail.

I work at a major cancer center with more than 10,000 employees. My colleagues, of all races, religions, nationalities, genders, sexual orientations, political affiliations, all come together day after day for the same cause: to conquer cancer. Period. Patients come from all over the world to be seen by experts in their disease. We do not ask, “To whom do you pray?” as a part of the history and physical. We do not ask, “To which government are you loyal?” We treat, we care for, we heal. We fight for our patients’ dignity throughout their illnesses and at the end of their lives. We stand with them and their families. We share their hopes and their fears. Their successes are ours to celebrate and their failures are ours to grieve.

People in the world are scared right now. Those who are scared now felt safer on November 7th, and those who were scared on November 7th feel safer now. Fellow creatures in pain. As I was driving to work the other day and quite honestly, musing on the election results, I noticed a sign that said, “Hill blocks view.” Therein lies the metaphor: We see the worst parts of ourselves when our security and our stability is threatened. I’ve experienced this first-hand. We, as physicians, preside over what are often the most terrifying moments of people’s lives. Our job is to understand and clarify those fears and to mitigate any exacerbating factors. We do not dismiss them as fabricated or unfounded. What would it look like if we did? What if societally, we adopted this principle of “selective tolerance” and how would it affect our immunity?

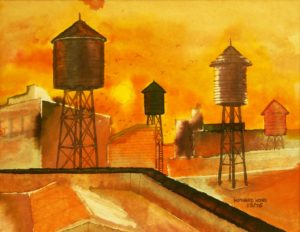

My grandfather-in-law, a Japanese-American (who had never even visited Japan), spent a number of his formative years interned in a camp after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Could this happen again in our lifetime? I don’t know. Could my [same-sex] marriage be federally nullified? I don’t know. Am I overreacting? I don’t know, but the line between simply doing what is right and standing up for what is right has become more prominent. Grandpa Horii died at 92 years old, a successful architect, professor and artist, father, grandfather and husband, whose resilience and determination were nothing short of awe-inspiring.

I’m a big-picture thinker. I’m moved by systemic reform. I’ve been unable to wrap my head around the big picture lately, so I’m attempting to train myself to see smaller-scale… daily human interactions. My family, my profession, not my politics.

In his incredibly moving New Yorker piece called “Health Of The Nation,” Atul Gawande writes, “Our hospitals and schools didn’t suddenly have Reaganite values in the eighties, or Clintonian ones in the nineties. They have evolved their own ethics, in keeping with American ideals…The helping professions will stand by their norms… Our fundamental values — values such as decency, reason, and compassion.”

Ganbare is a Japanese term of encouragement, often likened to the American expression, “Hang in there!”

In the fight to preserve decency, reason and compassion, “ganbare,” my friends.

Well-written and thoughtful. Thank you for sharing – Ganbare!

Thank you for reading, Greg. All the best.

very nicely written !

awsome.

thanks a lot. Ganbare!

Thank you, Ganbare!