April 16th, 2013

Selections from Richard Lehman’s Literature Review: April 16th

Richard Lehman, BM, BCh, MRCGP

CardioExchange is pleased to reprint selections from Dr. Richard Lehman’s weekly journal review blog at BMJ.com. Selected summaries are relevant to our audience, but we encourage members to engage with the entire blog.

NEJM 11 Apr 2013 Vol 368

Fibrinolysis or Primary PCI in STEMI (pg. 1379): When it became clear about ten years ago that immediate percutaneous coronary intervention was the treatment of choice for myocardial infarction, I advised readers to have their MI on a Thursday morning in a large city where there was a sporting chance that there might be a fully staffed cardiac catheter suite ready to receive them. The treatment of first choice remains very challenging to provide: so how much worse is the treatment of second choice—immediate (prehospital) fibrinolysis, followed by PCI at relative leisure (6-24hrs later)? The answer is that the two strategies are equally good when judged by a composite end-point of death, shock, congestive heart failure, or reinfarction up to 30 days. The only drawback was a greater incidence of cerebral haemorrhage in the primary thrombolysis group, due to their cocktail of tenecteplase, clopidogrel, and enoxaparin. Dose adjustment helped to reduce this in the later stages of the trial. Overall, this is very good news for those working out how best to provide safe MI services around the world.

BMJ 13 Apr 2013 Vol 346

Effect of Lower Sodium Intake on Health: The BMJ has published a systematic review of the effect of lower salt intake on health. The conclusion dutifully states, “Lower sodium intake is also associated with a reduced risk of stroke and fatal coronary heart disease in adults. The totality of evidence suggests that most people will likely benefit from reducing sodium intake.” In Thatcher week, should we reply “Rejoice!” or “No, no, no!”? I suggest the latter. The summary in the printed BMJ says it all: “Low and very low quality evidence suggest that lower sodium intake is associated with reduced risk of stroke, fatal stroke, and fatal coronary disease in adults.” Again, there is a good response from Copenhagen. “The conclusion of the analysis is not justified by the data, but that is not the issue. The interesting question is why BMJ use 20 pages on the publication. The answer may be that the science of salt is not scientific, but political.”

Effect of Increased Potassium Intake on CV Risk Factors and Disease: But potassium is probably good. I’m not saying the evidence is perfect—it never can be—but this systematic review concludes “High quality evidence shows that increased potassium intake reduces blood pressure in people with hypertension and has no adverse effect on blood lipid concentrations, catecholamine concentrations, or renal function in adults. Higher potassium intake was associated with a 24% lower risk of stroke (moderate quality evidence).” Eat bananas and tomatoes. Drink fruit juice. Accentuate the positive.

April 13th, 2013

FDA Schedules Another 2-Day Avandia Advisory Panel

Larry Husten, PHD

Once again the controversial diabetes drug rosiglitazone (Avandia, GlaxoSmithKline) will be the subject of a 2-day FDA hearing. According to a meeting announcement scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on April 15, the Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee and the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee will meet on June 5 and June 6 to “discuss the results of an independent readjudication of the Rosiglitazone Evaluated for Cardiovascular Outcomes and Regulation of Glycemia in Diabetes (RECORD) trial.”

The RECORD trial was one of the major topics of contention at the 2010 rosiglitazone advisory panel. Designed ostensibly to test the effect of rosiglitazone on cardiovascular outcomes, RECORD was the subject of intense and often brutal criticism from FDA reviewers and Steve Nissen. One result of the 2010 panel was that GSK commissioned Duke University to perform an independent review and analysis of RECORD. This review will apparently be the subject of the June meeting.

April 11th, 2013

Cuban History Offers Important Lessons For Global Health Today

Larry Husten, PHD

A large new study from Cuba shows the impressive benefits that can be achieved with weight loss and increased exercise. Much more ominously, the same study shows the dangers associated with weight gain and less exercise.

In the study, published in BMJ, researchers took advantage of a “natural” experiment that occurred in Cuba as a result of a major economic crisis in the early 1990s. Relying on 30 years of superb health statistics available in the country, the researchers analyzed the dramatic health effects associated with the economic crisis, which lasted from 1991 through 1995, and the subsequent recovery.

During the economic crisis, caloric intake decreased and physical activity increased, resulting in an average, population-wide 5.5-kg reduction in weight and a very high (80%) proportion of the population classified as physically active. Following the crisis, the pattern reversed itself: weight increased by an average of 9 kg between 1995 and 2010, and today only 55% of the population is considered physically active.

Prior to the economic crisis, the incidence of diabetes increased slowly. It then fell sharply during the crisis by 53%. The incidence of diabetes remained lower than before the crisis for several years but subsequently increased by 140% from 1996 to 2009. The changes in diabetes incidence were followed, after a lag, by similar changes in diabetes mortality.

From 1980 to 1996, mortality from coronary disease decreased by 0.5% per year. Following the crisis, from 1996 to 2002, mortality decreased by 6.5% per year. Subsequently, the decline in the rate of mortality slowed to pre-crisis rates. Stroke mortality and all-cause mortality followed a similar pattern.

The authors were careful to note that the generalizability of their findings was “uncertain,” but said the “data are a notable illustration of the potential health benefits of reversing the global obesity epidemic.”

April 11th, 2013

Treatment of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: Why Have All the Clinical Trials Failed, and What Can We Do About It?

Sanjiv Shah, MD and John Ryan, MD

We invited Sanjiv Shah, MD, author of a recent editorial in JACC:HF on heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) to answer some of our questions on what we do and don’t understand about this condition and how we are closing the gap.

Dr. Ryan: Are the negative trials that are seen in HFpEF a result of the disease process or the trials?

Dr. Shah: I think it’s a little bit of both, but primarily a problem of trial design. HFpEF is a heterogeneous syndrome with multiple etiologies and pathophysiologies, and it is also a syndrome of the elderly who typically have many competing risks for morbidity and mortality. I like to use the analogy of cancer to describe the problem with HFpEF clinical trials. Imagine a world where we designed clinical trials to tests new drugs for “cancer” regardless of type. That would seem silly to us, and yet that’s what we do for HFpEF. We take a heterogeneous syndrome and we try to use a “one size fits all” approach. I believe that if we are able to come up with a categorization system for HFpEF, we may have better luck designing clinical trials for therapies targeted at specific subsets of HFpEF.

Dr. Ryan: You mention in your editorial that we need “an established paradigm for the routine testing” of patients with HFpEF. Why have we failed to define a standardized work up for HFpEF patients?

Dr Shah: The first problem is that HFpEF is not easy to diagnose. There is no low ejection fraction to easily spot and call it “heart failure”. HFpEF is a common syndrome but I believe that it is often missed because so many other disease processes can present like HFpEF. So there has to be a low threshold to think about the diagnosis so that we can diagnose it more routinely and then work it up in a standardized fashion. The next problem is that currently several types of providers care for patients like HFpEF (which is necessary because HFpEF is common). However, family practice physicians, internists, cardiologists, and heart failure specialists may work up HFpEF patients in very different ways, and no one type of physician is necessarily more correct than the other. Nevertheless, until we have good evidence-based diagnosis and management protocols for HFpEF, we need dedicated HFpEF clinical programs to facilitate clinical trials and other research in this area. Such research would help us develop the standardized protocols that physicians sorely need when diagnosing and managing these patients.

Dr. Ryan: What is your idea to improve the trials and outcomes in HFpEF and why is it important?

Dr. Shah: As I alluded to above, I think the most important first step would be to develop a rational classification system for HFpEF, and then develop targeted therapies for HFpEF subgroups based on etiology and pathophysiology. In addition, I believe that clinical trials would benefit from more specific enrollment criteria for HFpEF patients. However, adding additional inclusion criteria for HFpEF clinical trials (e.g., requiring a certain degree of left atrial enlargement, the presence of elevated pulmonary artery pressure, or a specific cut-off for tissue Doppler e’ velocity) would likely make enrollment more difficult. It is therefore critically important to develop dedicated HFpEF clinical programs simultaneously with more targeted clinical trials. In our own HFpEF program at Northwestern, we have shown that having a dedicated HFpEF program facilitates enrollment into clinical trials. In addition to establishing HFpEF specialty centers that can enroll large numbers of patients, my hope is that we can harness the power of deep phenotyping of HFpEF patients (in multiple phenotypic domains) and that these results will allow us to match the right treatments to the right patients, thereby improving the outcomes for this common and morbid syndrome.

April 11th, 2013

Bleeding Avoidance Strategies for PCI in Women vs. Men

Stacie Luther Daugherty, MD, MSPH and John Ryan, MD

John Ryan interviews Stacie Daugherty, lead author of a study recently published online by JACC on differences in rates of bleeding and bleeding avoidance strategies (BAS) between women and men undergoing PCI.

THE STUDY

Investigators used data from the CathPCI registry to analyze the use of BAS (radial access, bivalirudin, vascular closure devices, or any combination) and bleeding outcomes in men and women. They found that despite similar rates of BAS use in men and in women, bleeding complications occurred significantly more frequently in women. Compared with no BAS, the use of BAS reduced bleeding rates to a similar degree in men and women, but because of the higher overall bleeding rates in women, the absolute reduction in women was much greater than in men.

THE AUTHOR RESPONDS:

Ryan: Were you surprised that the overall rates of BAS use were comparable in men and women?

Daugherty: Given previous data showing higher bleeding rates in women compared with men after PCI, we hypothesized that a portion of this difference might be related to less use of BAS in women. Our findings suggest that women and men undergoing PCI equally receive any form of BAS. Furthermore, other researchers have demonstrated a risk–treatment paradox in BAS use whereby higher-risk patients receive BAS less often than lower-risk patients; we found that the paradox applies to both men and women. This is particularly concerning for women, because a larger proportion of them fall into the high predicted bleeding risk category compared with men (53% vs. 23%; P<0.01). Therefore, one could argue that BAS should be used more frequently in women than men given their higher predisposition to bleeding.

Ryan: What are the major obstacles to using BAS for practitioners?

Daugherty: Due to the observational nature of our data, we were unable to determine the reasons why practitioners did not employ BAS. For example, patients may not have received a radial approach due to inappropriate anatomy; closure devices may not have been used due to high arteriotomy sites; or radial access or closure device use may have been attempted and failed. Therefore, a portion of those who did not receive BAS may not have been ideal candidates. We also suspect that there may be variation by site as to which BAS, if any, is most commonly used. Site-based differences in the use of bleeding avoidance strategies may be influenced by local culture, operator preference, operator experience, laboratory volume, laboratory protocols, and costs. We are interested in examining these potential factors in future studies.

Ryan: Do you feel that a 75% use rate is sufficient, and how would you increase the use of BAS?

Daugherty: Current clinical guidelines for PCI recommend considering bleeding risk in all patients; however, the guidelines do not provide specific recommendations for when BAS should be used. Therefore, the expected or appropriate rate of BAS use remains unclear. There has been substantial debate around the effectiveness of different BAS strategies, particularly closure devices. The evidence supporting reduced bleeding with the use of bivalirudin and radial approach is more robust. Further research is needed to help define the most effective BAS and optimizing patient selection for these therapies.

April 11th, 2013

Journals, Journals, Everywhere

Tariq Ahmad, MD, MPH

One of my cardiology colleagues seemed hard at work at his computer recently. “Working on that paper for the New England Journal of Medicine?” I joked. “No,” he replied, “I’m writing a review for the Journal of Atrial Fibrillation.”

I had never heard of this journal and, in an attempt to feign familiarity, nodded knowingly.

Getting back to my desk, I Googled the journal and was transported to a fairly busy website with articles by experts, news about atrial fibrillation, and numerous links for article submission. There was even an adjoining afib blog and patient page. The only thing missing was a section on subscriptions, generally the lifeblood of a publication. This, I found soon enough, was because it is an open-access, online-only journal.

The exercise made me curious about how many cardiology journals existed.

I searched the internet for published subspecialty cardiology journals, and lost count at about 150. Considering that a significant percentage of cardiology-related research is published in general medicine journals, it struck me as a fairly high number.

Surely, even 150 journals should be more than enough to house the research endeavors of cardiologists worldwide worth publishing.

Apparently not.

Instead of decreasing or staying constant, the number of journals has exploded over the last decade, with new publications at all ends of the quality spectrum. The leading cardiovascular journals — Circulation, JACC, and the European Heart Journal — have spawned a family of subspecialty journals, growing from 3 to 20. Numerous other journals, many of them open-access/online-only, have emerged.

While high-quality publications like the New York Times and Newsweek are on the road to bankruptcy, even middle-tier journals can stay viable while charging exorbitant amounts for subscriptions. Annual subscriptions can range from $170-$400 for 12 issues (by comparison, a subscription to the Economist costs $160 for 51 issues).

Several questions come to mind:

What has caused this upsurge in number of journals?

Are many of these studies helping advance the field or just overwhelming us with data?

Should there be any barriers to the creation of online open-access journals?

Does creating more subspecialty journals contribute to the creation of too much information, about small aspects of the field, such that specialists move closer to “knowing everything about nothing”?

In this state of information overload, how should cardiologists keep up with new findings?

The point can be made that more data improve clinical decision-making, and therefore, patient care. However, this may not necessarily be the case, as columnist David Brooks pointed out in a recent New York Times op-ed:

As we acquire more data, we have the ability to find many, many more statistically significant correlations. Most of these correlations are spurious and deceive us when we’re trying to understand a situation. Falsity grows exponentially the more data we collect. The haystack gets bigger, but the needle we are looking for is still buried deep inside.

That said, perhaps the driving force for more journals can be best described by some sage advice my mentor gave me recently: “A publication is a publication.”

April 10th, 2013

Scientific Misconduct: From Darwin and Mendel to Poldermans and Matsubara

Larry Husten, PHD

Responding to recent episodes of scientific misconduct in cardiovascular research involving once prominent cardiovascular researchers, the editor of the European Heart Journal, Thomas Lüscher, has written an editorial discussing the significance of the new cases and placing them in a historical context that includes allegations of scientific misconduct by Mendel and Darwin, among many others.

Lüscher writes that scientific misdoncuct “is morally inappropriate, damages the reputation of research and journals in which its products are published, may endanger patients, and misuses grant money of federal and private institutions.” Nevertheless, he concludes, “we must avoid an atmosphere of distrust, as trust is the essence of scientific exchange and progress.”

In his editorial, Lüscher announces a further response by the EHJ to the Don Poldermans case and links it to the more recent Hiroaki Matsubara case. (Poldermans was a prolific Dutch cardiovascular researcher who was fired by the Erasmus Medical Center; Matsubara is the Japanese researcher who was the principal investigator of the Kyoto Heart Study of valsartan in heart failure.)

Poldermans was the first or senior author in seven papers published in EHJ. Lüscher writes that the chairman of the Poldermans investigative committee “made it clear that the vast amount of publications led by Poldermans over the last decades made it impossible to assess their scientific validity in all cases.” As a result, Lüscher announces that “the editors of the European Heart Journal therefore would like to make an expression of concern related to the papers where Poldermans was the responsible author.”

The EHJ had already announced — without any substantial details — the retraction of the main paper of Matsubara’s Kyoto Heart Study. Although Lüscher provides no new substantial information about the case, he links the EHJ retraction to five other retracted papers from the Kyoto Heart study group published in Circulation Journal, the American Journal of Cardiology, and the International Journal of Cardiology.

April 9th, 2013

Quinidine Unavailable in Most of the World

Larry Husten, PHD

Quinidine — the only drug known to be effective in preventing lethal ventricular arrhythmias in people with several rare conditions, including Brugada syndrome, idiopathic ventricular fibrillation (VF), and early repolarization syndrome — is no longer available in much of the world.

In a study published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Sami Viskin and colleagues surveyed physicians around the world about the availability of quinidine in their country and received responses from 273 physicians in 131 countries. In 76% of the countries quinidine was not available at all. In another 10% quinidine was available only through a regulatory process that can take several days to several months to obtain the drug. Quinidine was easily obtained in only 14% of countries.

The researchers also obtained information about 22 patients with serious arrhythmias that were probably or possibly related to the unavailability of quinidine.

In most other cases of drug shortages, the authors note, the unavailability of life-saving drugs is usually related to the high cost of the drugs. In this case, however, the lack of availability is due to the “low price and restricted indication for a low prevalence disease, rendering unfavorable pharmaceutical market forces from the perspective of industry.”

Quinidine was once a frequently used antiarrhythmic agent, but its use declined sharply with the advent of newer agents and evidence showing an association with harm in clinical settings. However, the authors write, the disappearance of quinidine from the market in 2006 “was clearly problematic from the ethical point of view since the unique effectiveness of quinidine for VF prevention and for controlling arrhythmic storms in patients with idiopathic VF had been known for more than two decades at that time. Moreover, the laboratory and clinical evidence establishing the high efficacy of quinidine in the management of the Brugada syndrome, particularly for arrhythmic storms, were well known at the time quinidine production was discontinued.”

The authors write that “the lack of quinidine accessibility is a serious medical hazard at the global level.” They recommend that professional medical organizations coordinate with national healthcare authorities to ensure quick and inexpensive access to quinidine in all countries. Until then, referral hospitals “should ensure an adequate supply of quinidine for immediate access in medical emergencies.”

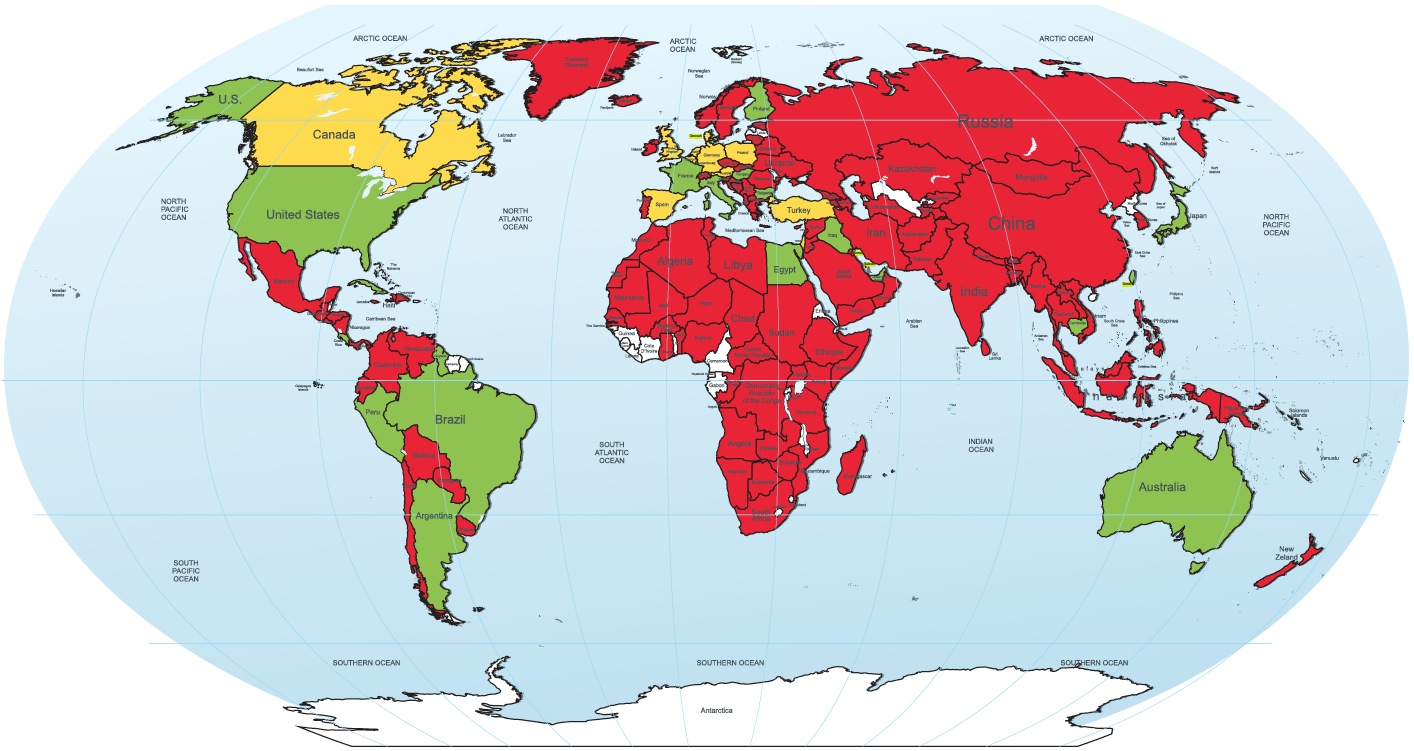

World map of quinidine availability.

Color code: green = quinidine is readily available; red = quinidine is not available;

yellow = available with restrictions; white = no data

(Reproduced with permission from the Journal of the American College of Cardiology)

April 9th, 2013

The TACT Investigators Respond to Questions

Gervasio Antonio Lamas, MD, Daniel Mark, Christine Goertz, DC, PhD, Robin Boineau, M.D., M.A., Kerry L. Lee, Ph.D. and Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, SM

JAMA’s publication of the NIH’s Trial to Assess Chelation Therapy (TACT) has reignited a heated debate about the trial. The TACT investigators have generously agreed to respond to questions posed by CardioExchange’s Harlan Krumholz. The TACT investigators who participated in this interview are Gervasio A. Lamas, Christine Goertz, Robin Boineau, Daniel Mark, Richard L. Nahin, and Kerry L. Lee. (To read CardioExchange’s news story on the study, click here.)

Krumholz: How was the time to stop the study selected? Statistical significance seems to have been reached just as the study was halted.

TACT Investigators: The TACT protocol always specified that the last patient enrolled in the trial should have 1 year of follow-up (see design paper). Also, as clearly explained in the TACT report in JAMA and amplified in the Supplementary Online Appendix, the decision to enroll 1700 patients occurred in 2009, well before the end of the trial. Thus, the trial results were significant based on (a) enrolling the specified number of patients, (b) following them for the prespecified period of time, and then (c) closing the trial and analyzing the data according to the prespecified statistical plan. The timing of when the study stopped was pre-planned — it had nothing to do with whether or when statistical significance was achieved.

The primary endpoint has been criticized as “soft.” How was it chosen, and has it been used in other studies?

The primary endpoint consisted of time to the first occurrence of the following major adverse cardiovascular events: death, MI, stroke, coronary revascularization, or hospitalization for angina. Combined endpoints are used when the most important endpoint to provide proof of efficacy, all-cause mortality, is likely to occur so seldom that an impractical and unaffordable number of patients and patient-years of follow-up would be needed to have enough statistical power to detect a difference between groups. In a stable coronary disease population, the incidence of mortality is low, so a combined primary endpoint is necessary for most studies. As we were planning the study, we selected a population very similar to that of the WIZARD study, which used a primary endpoint similar to ours. Other studies with similar combined endpoints, particularly including revascularization, are JUPITER and ACCELERATE.

How does the unexpectedly large number of patients who withdrew consent affect the study’s findings?

Simply put, patient withdrawal limits the observation time for the patient, as well as the likelihood that an event will take place and be detected. Consequently, it limits statistical power to detect a difference between groups. In TACT, more placebo patients than active-infusion patients withdrew consent. This complicates the situation, as more actively treated patients are likely to have their endpoints counted, and there was less follow-up time to detect and count placebo events. Thus, the effect on the study is to push the results toward the null. Yet, in spite of this rather daunting problem, the intent-to-treat analysis of TACT trial was still positive.

The editors at JAMA asked us to perform sensitivity analyses in which we would make assumptions regarding what might have happened to the missing patients and how that might have altered the study results (see eTable 8 of the online Appendix). I quote the conclusion in p. 32, although the full text and table are well worth reading.

“Based on the other data observed in the trial and because the baseline risk factors of the patients who withdrew consent were very similar in the two arms of the trial, the most plausible scenarios in eTable 8 are those where the percentages of events among the withdrawn or lost patients in the two arms are nearly equal or slightly favor the active arm. However, the comparison of the two arms remains significant at the 0.036 level if the relative increase of events in the active arm is as much as 20% higher than in the placebo arm, and even generally if the percentage of events in the active arm is 25% higher than in the placebo arm. The hazard ratio for all of these scenarios remains in the range of 0.80 to 0.84, the p-values are quite robust, and significance of the treatment effect is maintained, not only for the scenarios for the withdrawn or lost patients that would be considered most plausible, but also for scenarios that are unfavorable to EDTA chelation.”

Was the study design changed midway through the trial?

The basic study design was never changed. The sample size was changed while maintaining statistical power by lengthening follow-up time. Thus, the key protocol feature, 85% power to detect a 25% difference, was unchanged throughout the study. Changes in sample size are fairly common in clinical trials. Other recent clinical trials studying coronary disease patients, such as OAT and FREEDOM, reduced the sample size due to difficulty in implementation or recruitment. Their results have not been questioned.

Some people have raised ethical questions about the study. Specific comments include failure to conduct the investigation in accordance with the signed statement and investigational plan; to report promptly to the IRB all unanticipated problems involving risk to human subjects or others; to prepare or maintain adequate case histories with respect to observations and data pertinent to the investigation; and to keep good records on investigational drug disposition with respect to dates, quantity, and use by subjects. Can you set the record straight on these issues?

The above comments and questions link to an FDA site visit to a TACT site. The principal finding was that the delineation of responsibility log was not filled out correctly. The study coordinator who was obtaining consent was not listed on the log. This led to a daisy chain of findings reported by the FDA. I want to point out that at no time were patients endangered. A corrective action plan involving retraining and site visits was put in place. The FDA’s concerns were resolved, and the site continued study activities. We invite you to read in detail the online content in Dr. Bauchner’s editorial, which describes many of these issues in much greater detail.

Much of the criticism and controversy surrounding TACT was originated by several small, self-appointed groups with a history of aggressive opposition to CAM practices and to TACT in particular, as they feel that 1) CAM practices should not be studied; 2) if studied and the results are negative, the trial should be condemned as a waste of money; and 3) if studied and the results are positive, the trial should be condemned as incompetently and unethically carried out, and the results discounted. Obviously, TACT has received the 3rd response. We ask our cardiology colleagues to look at the study critically, without emotion, and ask themselves if they would feel the same way about our results if the words EDTA chelation never appeared, and instead “stem cell” or “new statin” appeared. We believe that the debate should focus on the unexpected biological activity of chelation therapy rather than on spurious allegations that TACT investigators were involved in willful wrongdoing that affected the results of the trial.

A major comment concerns the components of the chelation therapy, specifically about the inclusion of procaine and heparin and their possible effects on cardiovascular outcomes. Why were they included, and do you think they had an effect?

The NIH RFA to which we responded had gone through NHLBI and NCCAM Councils and called for a definitive trial of EDTA chelation therapy, as it was currently being implemented in clinical practice. When we looked into the infusions, we found that they included many compounds, not just EDTA. Therefore, to achieve a result that would be consistent with how chelation therapy is actually used in practice, we chose to mimic precisely the most prevalent infusion in use. We have no reason to believe that a small amount of procaine or 2500 U of unfractionated heparin once weekly would affect outcomes to the extent that we found in TACT.

Another comment is that the placebo solution contained 1.2% glucose in order to match the osmolarities of the control and experimental solutions. Some people think that might have contributed to worse outcomes in the control group. What is your view of that possibility? What options did you consider for the placebo infusion?

We wanted to keep the placebo solution as simple as possible and not introduce an unexpected risk or benefit. Normal saline fit the bill, as we excluded patients who had active heart failure. The amount of glucose in 500 mL of 1.2% is 1.2 grams X 5 = 6.0 grams of glucose weekly. It is not plausible that this would lead to a greater coronary risk in diabetic patients. We also considered other iso-osmolar solutions such as D5W but felt these would have introduced a greater sugar load. Another option would have been a solution that encompassed all the ingredients except EDTA. However, as stated above, our intent was to investigate a treatment currently in use and determine whether it was safe and effective, rather than deconstruct the solution. The present design allows us to draw those conclusions.

Some people have claimed that unblinding might have biased the trial. Is there evidence of unblinding? Here is what one person wrote: “First of all, the chelation mixture is not stable and therefore must be mixed at the local site. The ascorbic acid, which must be injected into the mixture, is yellow in color and highly viscous. The work around for this problem is to cover ascorbic acid, chelation mixture and placebo syringes and bags with tinted translucent tape and to add concentrated dextrose solution to the placebo syringe to make it as viscous as the ascorbic acid.”

All necessary precautions were taken to ensure blinding was preserved in the study. Both the placebo and active infusions were shipped in identical refrigerated containers. Neither EDTA nor ascorbic acid is stable if shipped mixed with the other 8 components of the chelation solution. Thus, the shipped and refrigerated pack contained one syringe with EDTA (or placebo), one syringe with ascorbic acid (or placebo), and a bag for intravenous infusion with all the other components already mixed (or normal saline only).

The ascorbic acid solution has a pale yellow color, which upon mixing becomes indistinguishable from the clear saline placebo solution. The syringes containing ascorbic acid or placebo were covered in translucent yellow adhesive tape, thereby blinding the pale yellow color of ascorbic acid. In addition, ascorbic acid, in the concentration provided by the manufacturer, is viscous. The placebo ascorbic acid solution contained enough 50% dextrose to mimic the viscosity of the active ascorbic acid solution.

In his editorial, Steve Nissen complained that the sponsors had access to the results during the course of the study. Is this atypical for an NIH trial?

The TACT trial was conducted under a policy that allowed NHLBI and NCCAM program staff access to unblinded data. At all times there was a firewall between trial decision makers who were blinded and NHLBI staff who were unblinded, to prevent the possibility of improper influence by unblinded staff. NCCAM and NHLBI staff were unblinded primarily to assess safety issues with the intervention, not efficacy.

The goal of the Program Officers and other NIH personnel is to safeguard the integrity of the trial, not to sway the results either way. There is no indication of improper influence exerted by NHLBI or NCCAM program staff who saw unblinded data.

What was the result of the Office of Human Research Protections (OHRP) reports? Were there serious ethical breaches in this trial?

No serious ethical breaches occurred in the trial. In 2008 a self-appointed group of individuals, none of whom can be considered clinical trialists, with a record of strident opposition to CAM and to the study of CAM wrote to OHRP to complain about the scientific basis of TACT, the consent form, the investigators, and whether patients were properly notified of new developments. Given the misinformation disseminated on the internet and in print media, we want to emphasize that the study was never suspended by OHRP, NIH, or the DSMB. The study management team halted infusions for 1 week while the OHRP documents were examined and a plan of action developed. Infusions restarted a week later. New enrollments restarted 4.5 months later after a new consent form was approved and a Dear Patient letter was sent. The OHRP investigations closed on October 2009. Greater detail can be found in the online eAppendix that accompanies Dr. Bauchner’s editorial in the same issue of JAMA.

Was there evidence that the CAM sites cheated?

There is no evidence whatsoever that CAM sites cheated. In fact, we compared the effect of study therapy on patients enrolled in CAM vs. non-CAM sites (bottom of Figure 2 in the paper). The p for interaction was not significant.

Were there investigators who had violated the law – and how might unethical behavior by individuals who strongly believed in CAM have altered the trial? Is this any different from other trials where investigators are invested in the success of the intervention – or did this trial have specific issues that must be considered?

All investigators had an unrestricted license to practice medicine in their states, and they received human-subjects training, protocol training in person and online, research training, IRB approval, in-person site visits, and electronic data monitoring by the Data Coordinating Center at Duke.

All investigators brought strengths and weaknesses to TACT. Chelation sites had the clinical experience and infrastructure to administer chelation. Conventional sites had research experience but did not have the clinical experience and infrastructure to administer chelation. The purpose of training the sites was to develop a cohesive team with blended abilities. The lack of interaction of site-type with treatment bears this out.

Physicians who have an opinion and are invested in a treatment or technology frequently are open-minded enough to participate in clinical trials. If this were not the case, then clinical trials comparing PCI or surgery to each other or to medical therapy could never take place.

In their paper, the TACT investigators have taken a very cautious perspective, defending the trial but arguing that it should not influence practice. What was the point of doing the trial if a positive result is not enough to influence practice?

We were cautious scientists when we started, and we are cautious scientists now. We do not believe that we have enough data yet to recommend the routine use of chelation therapy for all post MI patients. We are continuing our analyses, now of the vitamin randomization and of the 4 factorial groups. When we finish and publish, we will be happy to revisit this question with you.

Did patients enrolled in TACT choose chelation above standard, evidence-based post-MI therapies?

No. In fact, the statistically and clinically significant benefit detected in post MI patients occurred in addition to maximal, but imperfect, real-world use of evidence-based post MI medications. In addition, chelation therapy did not interact with these medications, possibly suggesting a new mechanism of efficacy. This is an exciting finding that deserves further exploration.

- Gervasio A. Lamas MD

- Christine Goertz DC PhD

- Robin Boineau MD MA

- Daniel Mark MD MPH

- Richard L. Nahin PhD MPH

- Kerry L. Lee PhD

April 8th, 2013

Selections from Richard Lehman’s Literature Review: April 8th

Richard Lehman, BM, BCh, MRCGP

CardioExchange is pleased to reprint selections from Dr. Richard Lehman’s weekly journal review blog at BMJ.com. Selected summaries are relevant to our audience, but we encourage members to engage with the entire blog.

JAMA 3 Apr 2013 Vol 309

A New Era of Open Science Through Data Sharing (pg. 1355): With the runaway success of the Alltrials petition, it may seem as if everyone in the world has now agreed on the need to share every bit of data relating to every medical device and product used on millions of patients every day. In reality, this is going to be a very slow process, involving hard work over many years. Nobody is more aware of this than Joe Ross and Harlan Krumholz, whose YODA project is pioneering the methodology needed to do the job properly, in a way that few others have even considered attempting. The imperative to do this work is absolute, and is beautifully set out by them in this Viewpoint article. But the editor of JAMA, Howard Bauchner, announced in Oxford that he is planning to sit on the fence about Alltrials a while longer, consulting his editorial board in a few months’ time. In the meantime we can look forward to a piece on the “unintended consequences” of data disclosure by Robert Califf some time soon.

NEJM 4 Apr 2013 Vol 368

Primary Prevention of CVD with a Mediterranean Diet (pg. 1279): The most important event in England in 1950 (apart from my birth) was the publication of a slim volume called A Book of Mediterranean Food by Mrs Elizabeth David. In this book the British public, then thin and pale from ten years of food rationing, caught a vision of unlimited delicious sun raised produce, simple to cook and heavenly to eat. Unfortunately it never found its way into my parental home. The chapters of Mediterranean Food dealt with: soups; eggs and luncheon dishes; fish; meat; substantial dishes; poultry and game; vegetables; cold food and salads; sweets; jams, chutneys and preserves; and sauces. Growing up as the child of immigrant benefit scroungers living on national assistance, I rarely saw any of these. I have tried to catch up ever since, and suggest that you do the same.

As for what is called a Mediterranean diet by American researchers, I have no strong views. This seems to be the same as Elizabeth David’s diet, but with many of the nice things omitted. Compared with a standard low-fat diet, the PREDIMED diet achieved a reduction in cardiovascular events of about 30% over a median of 4.8 years, at which point the trial was stopped.

Effect of Platelet Inhibition with Cangrelor during PCI on Ischemic Events (pg. 1303): All the time I’ve been writing these reviews, drug companies have been trying to come up with new platelet inhibitors to break into the immense market dominated by aspirin and clopidogrel. Intravenous cangrelor was compared with an oral dose of clopidogrel (which could be 300mg or 600mg) in this study of 11,145 patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for a variety of reasons. And cangrelor definitely won, with a small but statistically significant reduction in the composite end-point (an absolute reduction of 1.2% in immediate thrombotic events or death). Overall, there was a 0.6% difference in stent thrombosis.

Atherosclerosis Across 4000 Years of Human History (pg. 1211): We sometimes hear it claimed that the so-called Mediterranean diet is good for you because it represents the historical ideal for human beings; arterial atheroma is our fault because we no longer follow this lost Edenic model. In reality, humans throughout their history have eaten a huge range of food, both as hunter-gatherers and as agricultural pastoralists – and whatever they have eaten, they have always developed some gunk in their arteries as they grew older. This wonderful study of atherosclerosis in mummies from around the world only goes back about 4,000 years, but the message is clear. The mean age of the bodies was just 36 years, but probable or definite atherosclerosis was noted in 47 (34%) of 137 mummies and in all four geographical populations: 29 (38%) of 76 ancient Egyptians, 13 (25%) of 51 ancient Peruvians, two (40%) of five Ancestral Puebloans, and three (60%) of five Unangan hunter gatherers (p=NS). Eat whelks. Or elks. Or nuts, or grains. Butter, olive oil or seal blubber. Beer. Mealy worms, peaches, samphire and locusts. Wine. Goats, mammoths, aurochs, whales, snails and anchovies. All these are good for you and bad for you.

BMJ 6 Apr 2013 Vol 346

CV events After Clarithromycin use in Lower Respiratory Tract Infections: About fifteen years ago, there was a lot of interest in the possibility that long term macrolide antibiotics might prevent coronary events by killing off Chlamydia pneumonia in arterial plaque. The ACES trial, published in 2005, finished off that hypothesis, and now the argument has turned full circle in a study which finds a higher rate of cardiovascular events in patients given clarithromycin in hospital for community-acquired pneumonia or infective exacerbations of COPD. The harmful cardiovascular effect of the macrolides seems very persistent in this and other studies, and takes some explaining. The drugs of greatest risk seem to be erythromycin and clarithromycin.

Ann Intern Med 2 Apr 2013 Vol 158

Discontinuation of Statins in Routine Care Settings (pg. 526): Once you have started taking a statin, is there ever any good reason to stop? I can’t think of any, except for intolerable side effects which do not respond to a change of agent. Yet more than half of this cohort of patients started on statins by doctors affiliated to the Massachusetts Hospital or Brigham & Women’s stopped their medication at some point. Fortunately this study found that contrary to widespread belief, “most patients who are rechallenged can tolerate statins long-term. This suggests that many of the statin-related events may have other causes, are tolerable, or may be specific to individual statins rather than the entire drug class.” The paper is behind a paywall, but the guide for patients is not.