February 14th, 2014

Is It Time for an Alternative to CME?

Nicholas Bergfeld, BS, BA

My father, now in his third decade of practicing family medicine, is always willing to give me advice. But his greater joy seems to come from showing me how much I don’t know. He leaves CME clippings from academic journals on my desk or the kitchen counter, to read when I’m home for the holidays. The American Family Physician journal’s photo quiz is a favorite of his, and while I am frequently stumped, occasionally the answer actually is chalazion. He, on the other hand, is quite adept, and I haven’t seen him get one wrong.

Considering my father’s broad knowledge of all things primary care, I was surprised when we got into a discussion about aspirin over dinner at a restaurant known for its extensive salad bar.

“You eat well and are health conscious,” I said. “But given your age and our family history of MI, would you benefit from taking aspirin for prevention?”

His response was a negative: “There wouldn’t be any benefit, and it would expose me to the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.”

So I broke dinner etiquette and placed my smartphone on the table. I accessed the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Electronic Preventive Services Selector (ePSS). The ePSS is a well-constructed application that aggregates U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations so that they are relevant to the patient in front of you and easy to read on the spot.

I entered the few required variables — on age, sex, pregnancy status, tobacco use, and sexual activity — and showed him the level A recommendation: aspirin. A helpful link to the NIH’s cardiovascular disease risk calculator is also embedded in the application, and within a few moments we could determine that his expected benefit from taking aspirin outweighed his risk for bleeding.

Our dinner reminded me of the perplexing inverse relationship, which this Annals review article seemed to detect, between increasing physician experience and a variety of performance measures. If I use age less than 40 as a rough estimate for when things start going downhill, and assuming I work until age 65, I’ll reach my professional peak as a doctor in 13 years, with the next two-thirds of my career spent in slow decline. Presumably, I’ll start ordering prostate-specific antigen tests for all my male patients, tell my female patients to do routine self-breast exams at home, and order MRI of the lumbar spine for anyone with back pain.

Could it be true that as my time away from medical school graduation increases, the likelihood of my adherence to standards of care decreases? One review article lists 293 potential barriers to adherence, broadly listed under categories of knowledge, attitude, and behavior. From a regulatory perspective, testing someone’s knowledge is the easiest way to assess competence, and formal interactive CME sessions have some evidence of improving physicians’ performance.

But even if dwindling knowledge were to explain aging-related declines, the Institute of Medicine and many others nonetheless believe that the CME system is a very poor way to address the knowledge deficit. I wholeheartedly agreed with this when I examined various states’ CME requirements and realized I would be halfway done with certification in Arkansas after completing 10 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™ opportunities. My list:

- Is Employment the Only Alternative? Improving Care Coordination through Clinical Integration

- Delivery Reform Implemented? Payment Models that Reward Your Performance

- The Final Piece of the Puzzle: Customizing the Payment Model to Fit Your Practice

- Health IT Adoption Online Modules

- Health IT Workflow Analysis Tutorials

- Principles for Physician Employment

- Organized Medical Staff Section Webcast

- Doing the Right Thing for Our Patients — Leading as a Professional

- Physician Employment Agreements (AMA Models)

- Physician Leadership during Challenging Times

It isn’t entirely clear how my choices from this list would translate into better patient care, but I’d certainly know more about physician employment agreements. So I find myself wondering whether CME will ever improve doctors’ ability to care for patients. Suppose that we learn the most up-to-date way to approach a medical condition upon first encounter, when we have no pre-formed mental heuristics, and that with increased exposure the need to consult the literature decreases. Bias begins to set in, and the benefit of future knowledge exposure diminishes.

Consider, instead, if the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and insurance companies were empowered to detect deviant prescription and billing practices that indicate poor-quality care. This information could then be sent to each state’s accrediting body, to determine whether a formal interactive class is appropriate. With this approach, behavior rather than knowledge is the trigger, which makes for a more targeted intervention.

Incidentally, my father still does not take aspirin. He refuses any medication and prides himself on not having used a pain reliever since 1975.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

Share your thoughts on the best way for doctors to remain on their game as they age.

February 14th, 2014

FDA Once Again Rejects New Indication For Rivaroxaban

Larry Husten, PHD

The third time wasn’t the charm. The FDA today turned turned down — for the third time — the supplemental New Drug Application (sNDA) for rivaroxaban (Xarelto, Johnson & Johnson) for use in acute coronary syndrome patients to reduce MI, stroke, or death. In addition, the FDA — for the second time — turned down the sNDA for rivaroxaban in the same population for the reduction of stent thrombosis.

The complete response letters come as little surprise, since an FDA advisory panel last month strongly recommended against approval for the indications. The large amount of missing data from the pivotal ATLAS ACS 2-TIMI 51 trial has been the source of the company’s inability to gain the ACS indications. Although J&J has made considerable efforts to fill in the missing data, the FDA reviewers and panel members did not believe the data were reliable enough to reach firm conclusions about the relative safety and efficacy of rivaroxaban for use in ACS.

“We remain committed to providing patients who have suffered from acute coronary syndrome with additional protection against stent thrombosis and secondary life-threatening cardiovascular events,” said a J&J executive in a statement. “We are evaluating the contents of the letters and will determine the appropriate next steps.”

FDA Rescinds Xarelto REMS

In a separate development, the FDA has rescinded the Xarelto REMS (Risk Evalaution and Mitigation Strategy). The company had been required to communicate the risks of an increased risk of thrombotic events when the drug was discontinued without an adequate alternative anticoagulant and was of decreased efficacy when not taken with the evening meal.

February 13th, 2014

Fellows: Want to Blog for CardioExchange at ACC.14?

Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, SM and John Ryan, MD

CardioExchange editors Harlan Krumholz and John Ryan are looking for fellows to blog for CardioExchange at the American College of Cardiology’s Annual Scientific Sessions from March 29th through the 31st in Washington, DC.

If you are interested in blogging, please contact us. We look forward to hearing from you!

February 13th, 2014

Roman DeSanctis, One of the Greats, Retires

Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, SM and Roman DeSanctis, MD

CardioExchange Editor-in-Chief Harlan Krumholz interviews Roman DeSanctis, one of the most influential physicians of his career, upon his retirement.

Krumholz: I met Roman DeSanctis when I was a third year medical student. I have always said that he and Kanu Chatterjee are the reasons that I am in cardiology. They shared this towering clinical ability with great respect for the clinical history and physical examination – and an intense interest in the patient.

When I heard that Roman was retiring I thought of what it must have been like in 1951 when Joe DiMaggio retired. Roman was like DiMaggio in that he had talent and charisma – and people were drawn to him. And with patients it was magic – he connected with them – and they trusted him. It was something to see.

It is a loss for cardiology – I think that there will not be cardiologists in quite the same mold. I wanted to pull him into CardioExchange to have the chance to connect with him again. I wanted him to know that he would continue to be an inspiration to me. I wanted to thank him.

For our readers I posed the following questions to him:

Over all the years, what is your favorite memory of your career in cardiology?

DeSanctis: Clinically, there have been just too many memories to pick out a single one. The 18 years that I was involved as a cardiologist to the king of Morocco was a uniquely wonderful and interesting period of time. King Hassan II was a brilliant, sensitive man, and very important to the United States as a major, behind-the-scenes player in the Middle East; I was very fond of him. However, I’ve probably experienced my greatest satisfaction in helping to train scores of brilliant young men and women who have gone on to become leaders in cardiology, medicine, and health policy.

You have seen remarkable changes in cardiology over your career. We can do so much more now. Is there anything we lost in the progress?

DeSanctis: In 60 years we have gained so much in our ability to treat people with heart disease; but the advent of technology, IT, medicine that is driven heavily by financial considerations, and many other external forces have greatly diminished the personal, human aspects of taking care of patients.

What is your advice to the next generation?

DeSanctis: Remember that we are so fortunate to be in medicine; we go to work every day with no other purpose than to relieve pain and suffering and try to heal the sick. Is there a higher calling? Despite all of the external forces that make it harder for us to enjoy this noblesse oblige, we must never forget that the beauty and the essence of medicine is still the interaction between ourselves and the patients we serve. Doctors should never underestimate their importance to their patients.

February 13th, 2014

Perioperative Beta-Blockade: Between a Rock and a Hard Place

Prashant Vaishnava, MD, Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc and Kim Allen Eagle, MD

A recent article in the European Heart Journal by Graham Cole and Darrel Francis explores the continuing implications of the Don Poldermans research misconduct case. In light of this continuing controversy, we asked Prashant Vaishnava, Vineet Chopra, and Kim Eagle — all of the University of Michigan Health System — to comment on the use of perioperative beta-blockade.

Evidence of research misconduct has discredited the Dutch Echocardiographic Cardiac Risk Evaluation Applying Stress Echocardiography (DECREASE) family of studies. All studies investigated in the DECREASE family were found to be insecure because of flaws ranging from fictitious methods to fabrication of data to no evidence of written informed consent.

While we would not deny the far-reaching harms resulting from “perioperative mischief,” we are cautious about suggesting that implementation of the current European guidelines (informed, in part, on the indicted data from the DECREASE family of studies) may partially account for the projected 160,000 excess deaths annually in Europe as suggested by Cole and Francis (Note: The European Heart Journal has removed this paper while it conducts peer review. For more context, see Larry Husten’s Forbes article.). In an editorial titled, “Is the panic about beta-blockers in perioperative care justified?” the editorial staff of the European Heart Journal write that the contribution by Cole and Francis “failed to undergo peer review that is required for opinion pieces, if scientific statements affecting clinical practices are involved.” We share in these sentiments and would advocate for peer review of such potentially influential conclusions before broad dissemination. We offer the following comments:

1. The perioperative community is stuck between a rock and a hard place. On one hand, there are now discredited data. On the other hand, credible data employ a peri-operative beta-blocker regimen that is not representative of clinical practice. Specifically, the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled PeriOPerative Ischemic Evaluation (POISE) trial implemented 100 mg oral extended-release metoprolol or matching placebo 2-4 hours prior to non-cardiac surgery in 8351 patients with, or at risk of, atherosclerotic vascular disease. As indicated in the European perioperative guidelines, “the total dose of metoprolol succinate in the 24 h [was] 400 mg, at least in a number of patients.” This intensity of perioperative beta-blockade is rarely used in clinical practice, even in those maintained on chronic beta-blockade, much less in patients naïve to such treatment. More commonly, perioperative beta-blockade is initiated weeks in advance of elective non-cardiac surgery.

We recognize the POISE data as being credible, noting both the cardiac benefit and excess mortality associated with those randomized to beta-blockade; however, the intensity of perioperative beta-blockade used in this trial simply dilutes its clinical relevance. In being stuck between a rock and a hard place, it is difficult for guideline-writing authorities to make meaningful changes in reaction to data that lack credibility when the alternative is simply not fully applicable to current clinical practice.

2. Cole and Francis draw attention to a meta-analysis of “credible” data. The pooled effect size found by Bouri et al, while a step forward in excluding flawed data, is almost completely influenced by the singular effects of the POISE trial. Initiation of a course of beta-blockade before surgery was associated with a significant 27% increase in mortality (relative risk [RR] 1.27, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01 to 1.60, p=0.04). The clinical and statistical impact of these data may be questionable, however, given the proximity of the CI to unity. More importantly, the meta-analysis may do little more than corroborate the findings from POISE, a trial inherently limited by the protocol of beta-blockade used perioperatively.

3. Assuming that there are ~760,000 deaths/year following non-cardiac surgery, Cole and Francis suggest that as many as >400 excess deaths daily may be ascribed to the implementation of guideline-based care for perioperative beta-blockade. We suggest caution in attributing guideline-based care to actual mortality. We have long known that multiple barriers impact physician implementation of evidence-based care, and that guidelines are frequently not practiced. Such extrapolation, at best, may thus be inaccurate. Moreover, the attribution of such mortality is predicated on accepting that perioperative beta-blockade is indeed associated with adverse outcomes. Given the limitations of the POISE protocol and a meta-analysis that does little more than echo the findings of POISE, the suggestion that mortality is inextricably bound to perioperative beta blockade is dubious. Such an association may even be disingenuous when operating through a Bayesian lens of posterior probability.

For example, an appraisal of credible data must not overlook a recent retrospective cohort analysis by London et al. In this analysis of 140,000 patients treated at 104 U.S. Veterans Affairs medical centers, the authors found that the use of perioperative beta-blockade was associated with a reduction in 30-day mortality (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.65 to 0.83, p<0.001) in patients with two or more Revised Cardiac Risk Factors. Though we acknowledge the inherent limitations of this retrospective analysis, we pause in reaction to an indictment of beta-blockade. We must thus remain mindful of the ambiguity involved and the possibility that perioperative beta-blockade may be a useful practice.

4. More than two years have passed since allegations of research misconduct justly discredited the DECREASE family of studies and investigators. It is time to move beyond finger-pointing. Guideline writing authorities cannot be faulted for not reacting to negligent data when available evidence is difficult to apply to clinical practice.

We should leverage and advocate for what we know to be true: 1. The indiscriminant use of high doses of beta-blockers in the immediate hours before non-cardiac surgery is more likely to be dangerous than beneficial; and 2. Judicious use of titrated doses of beta-blockers in carefully selected patients with established coronary artery disease, may, in fact, reduce cardiovascular risk. When titrating beta-blockade to a target heart rate, the physician must be mindful that it is important to avoid perioperative hypotension at all times.

Ultimately, we should search for more definitive answers by advocating for a randomized clinical trial that is conducted honestly and transparently and uses a regimen that mirrors clinical practice.

February 13th, 2014

FDA Advisory Panel Recommends Against Approval of Cangrelor

Larry Husten, PHD

The FDA’s Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee today recommended against the approval of cangrelor, the investigational new antiplatelet drug from the Medicines Company. In a 7-2 vote, the panel first rejected an indication for the reduction of thrombotic cardiovascular events including stent thrombosis in patients undergoing PCI.

The panel also voted unanimously to reject a second indication, for the maintenance of antiplatelet therapy in patients with acute coronary syndromes or patients with stents who have discontinued antiplatelet therapy because they are awaiting surgery and are at high risk for thrombotic events. FDA reviewers, who had delivered mixed opinions for the first indication, had recommended a complete response letter for the second indication, since the company had failed to perform a trial showing clinical benefit for the indication.

Throughout the day panel members wrestled with problems with the pivotal CHAMPION PHOENIX trial, which attempted to remedy the deficiencies of two earlier negative trials. Although most panel members agreed that PHOENIX showed a benefit compared to the clopidogrel control group, the benefit appeared small and the committee was concerned that cangrelor may have received an unfair advantage because in the control group clopidogrel was not used ideally, since many subjects did not receive preloaded high-dose clopidogrel. An additional concern was that most of the difference between the groups was due to a reduction in periprocedural MIs. Panelists once again raised the question of the clinical relevance of this finding. Finally, the higher risk of bleeding with clopidogrel appeared to largely offset the observed benefits.

Panel member Milton Packer, who voted against approval, said that he wanted to vote yes and that he thought an antiplatelet agent with rapid on/off properties might well prove useful. But, he said, the sponsor had not demonstrated that cangrelor was superior to full dose clopidogrel.

February 12th, 2014

Case: Cardiorespiratory Arrest Requiring Intubation in a Patient with Diastolic Heart Failure

Saurav Chatterjee, MD and James Fang, MD

A 65-year-old African American woman with a history of hypertension, diabetes, and seizure disorder is brought to the ED via emergency medical services for respiratory distress requiring intubation. Two weeks earlier she was hospitalized for an exacerbation of acute diastolic heart failure; a transthoracic echocardiogram at that time documented an LV ejection fraction of 60% with inferolateral hypokinesis. Her current medications are amlodipine, metformin, and lamotrigine.

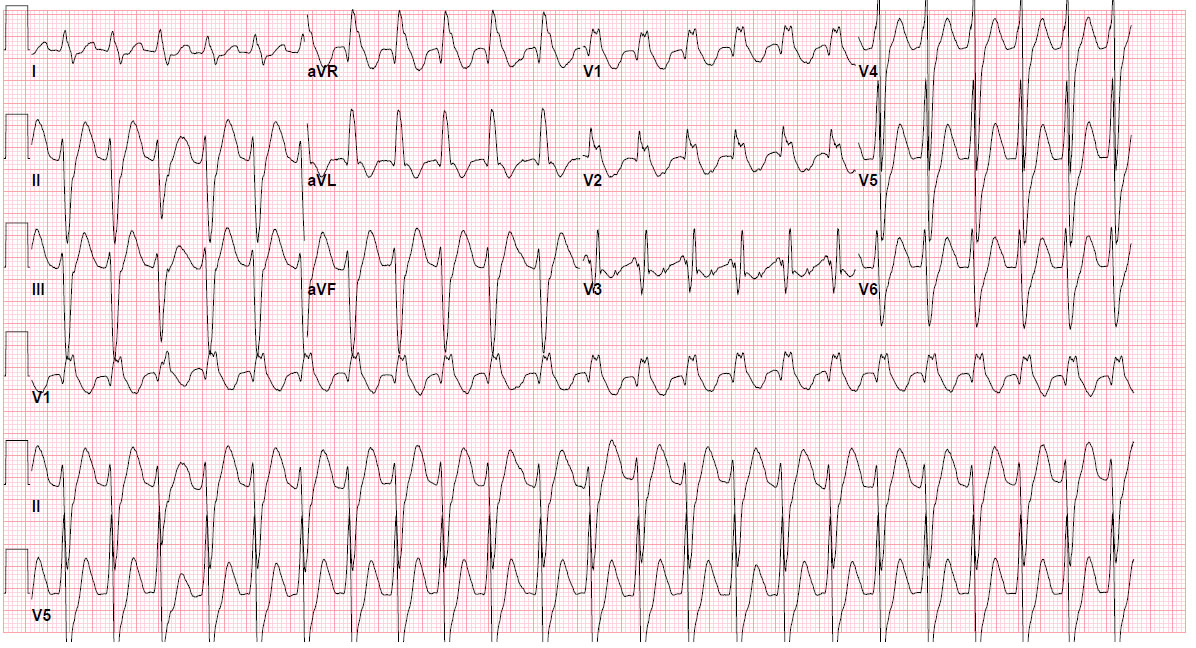

On her current arrival at the ED, she develops pulseless electrical activity requiring CPR for 5 minutes, after which circulation returns spontaneously. She has a heart rate of 122 beats per minute, a blood pressure of 112/74 mm Hg, and a ventilator-assisted respiratory rate of 14 breaths per minute. The patient is intubated but arousable, has diminished breath sounds, and has no murmur on cardiac examination. Her electrocardiogram is shown here:

Questions:

1. What does the electrocardiogram show?

2. What treatment would you recommend next?

3. Should the patient undergo cardiac catheterization? If so, why? If not, why not?

4. Should hypothermia be used in this situation? Explain your answer.

5. How does the patient’s neurologic status influence your decision?

Response:

James Fang, MD February 21, 2014

1. What does the electrocardiogram show?

In the setting of a wall-motion abnormality on echocardiogram (e.g., underlying heart disease), this wide-complex tachycardia (at least 120 ms to my review), RBBB-type, should be considered ventricular tachycardia (or an accelerated idioventricular rhythm due to heart rate) until proven otherwise, although atrioventricular dissociation is not apparent. However, the slow heart rate increases the temptation to consider this either sinus tachycardia or supraventricular tachycardia with aberrancy (e.g., RBBB). Using the Brugada criteria, a diagnosis cannot be made definitively without resorting to morphology of the QRS complexes, which suggests slow VT or accelerated idioventricular rhythm. A definitive diagnosis requires slowing the ventricular response to discern atrial activity and/or having documentation of the tachycardia’s onset.

2. What treatment would you recommend next?

Intravenous amiodarone would be reasonable in this setting until the diagnosis is clear. If the patient remains stable, a beta-blocker could also be considered. Synchronized cardioversion with adequate sedation would also be reasonable if the blood pressure is unstable or other signs of instability are apparent.

3. Should the patient undergo cardiac catheterization? If so, why? If not, why not?

In the setting of CAD risk factors (e.g., hypertension, diabetes) and a wall-motion abnormality on echocardiogram, CAD should be excluded. The patient’s episode of acute diastolic heart failure may have been related to dynamic mitral regurgitation in the setting of the inferior ischemia. Other etiologies, including pulmonary embolism, should also be considered in the differential diagnosis. An echo showing acute RV strain and/or PE protocol chest CT would be a reasonable test in the ED as well. Catheterization is not necessary emergently but should eventually be performed as part of the patient’s cardiovascular evaluation if an alternative diagnosis is not made.

4. Should hypothermia be used in this situation? Explain your answer.

Hypothermia is not necessary. Despite her PEA arrest and being intubated, the patient is arousable and not comatose.

5. How does the patient’s neurologic status influence your decision?

Her almost immediately arousable state suggests that the anoxic insult has been limited and would not therefore attenuate an aggressive approach to diagnosis or therapy. Her presentation was life-threatening and needs a diagnosis.

Follow-Up

February 27, 2014

It was decided that emergent catheterization would have a prohibitive level of risk for the patient. After extensive consultation with the attending physician and the patient’s family, an attempt was made to offer the patient the best possible chance at neurological recovery, by inducing hypothermia with surface cooling to 33°C. A CT scan ruled out acute intracranial pathology.

The patient was successfully cooled and then rewarmed, but unfortunately she never regained a meaningful level of consciousness. Brain imaging conducted at that time revealed diffuse neuronal injury, for which the cause was unclear given that the reported downtime of the patient was just a few minutes. Seven days after admission to the CCU, the family decided to proceed with terminal extubation, after multiple neurologic evaluations indicated that her prognosis was dismal.

February 11th, 2014

FDA Advisers: Meta-Analysis Does Not Prove That Naproxen Carries Lower CV Risk

Nicholas Downing, MD

Data from a meta-analysis suggesting that naproxen carries lower cardiovascular risk than other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug are not reliable, FDA advisers concluded on Tuesday. Consequently, they voted that naproxen should not get a new label based on those data, Reuters reports.

The meta-analysis, published in the Lancet in 2013, found that coxibs or diclofenac conferred increased risk for major vascular events, and ibuprofen showed increased risk for coronary events, relative to placebo. Meanwhile, no such risk increases were seen with naproxen.

The FDA advisers recommended that naproxen’s prescribing information stay as is until data from the PRECISION trial are available. That large, randomized trial is comparing naproxen with celecoxib or ibuprofen in patients with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis.

Originally published in Physician’s First Watch

February 11th, 2014

FDA Investigating Heart Failure Risk Linked to Saxagliptin

Larry Husten, PHD

The FDA said today that it is conducting an investigation of a possible increased risk for heart failure associated with the diabetes drug saxagliptin. Saxagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor, is marketed by AstraZeneca as Onglyza and Kombiglyze XR. (AstraZeneca recently completed the purchase of all rights to the drug from its manufacturer, Bristol Myers-Squibb.)

The investigation stems from findings from the cardiovascular outcomes trial SAVOR-TIMI 53, in which more than 16,000 patients with type 2 diabetes were randomized to saxagliptin or placebo. The trial, presented last year at the European Society of Cardiology and published in the New England Journal of Medicine, found no significant difference in the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, MI, or ischemic stroke. However, there was a significant excess in hospitalizations for heart failure in the saxagliptin group (3.5% vs. 2.8%, p=0.007).

The FDA said that it has requested trial data from the manufacturer and that it considers current information from the trial to be preliminary. The agency advised that patients should not stop taking the drug and should discuss their concerns with their healthcare professionals. The investigation of saxagliptin is part of a broader investigation into the cardiovascular risk of all drugs for type 2 diabetes.

February 10th, 2014

Is Fraudulent Science Criminal?

John Henry Noble Jr, BA, MA, MSW, PhD

John Henry Noble, Jr., offers his perspective on the issues raised by Richard Smith’s December 2013 blog post “Should Scientific Fraud Be a Criminal Offence?”, which appeared in the BMJ.

At a conference in Britain in 2000, Alexander McCall Smith asserted that research fraud should become a criminal offense. Since then, former BMJ editor Richard Smith has come to the reluctant conclusion that science is indeed failing in its public duty, calling research misconduct “terrifyingly common” and stating that “…hundreds of studies (and probably many more) that are fraudulent remain in the scientific literature without any signal that they are inventions.” Smith urges that research fraud be criminalized to put an end to it.

Bill Skaggs and Jeanne Lenzer, in their comments on Smith’s BMJ blog post, argue that criminalization is likely to be ineffective. Lenzer argues, “If people are reluctant to report their colleagues now, might they be even more reticent if they knew their (possibly incorrect) suspicions would mean their colleague would be dragged through public proceedings and possibly put in jail?” She advises against directly targeting individuals but instead says that the research enterprise should change how it incentivizes individuals’ behavior. She urges “putting researchers on salary and ending grant awards on an individual basis, and stop rewarding bad behavior by acknowledging that publishing 200 articles per year cannot represent careful work.”

Responding directly to Lenzer on the BMJ site, I quoted Machiavelli’s famous passage in The Prince:

We must bear in mind, then, that there is nothing more difficult and dangerous, or more doubtful of success, than an attempt to introduce a new order of things in any state. For the innovator has for enemies all those who derived advantages from the old order of things, whilst those who expect to be benefited by the new institutions will be but lukewarm defenders.

Nonetheless, I believe that we should do whatever we can to reform the system that incentivizes the wrong and harmful behavior of individual researchers. Criminalization of individual research fraud is necessary because that fraud debases and undermines the entire scientific enterprise on which human action and progress depend. Furthermore, the false claims of the perpetrators rise to the status of crime against society, insofar as they endanger public health by sullying and misdirecting the physician’s “standard of care.”

Consider the impotency of the U.S. Department of Justice’s practice of occasionally exacting large fines from corporations for the egregious harms they commit. The companies simply write off the fines as part of the cost of doing business, and the corporate leadership walks off scot-free to concoct another scam. Exacting a fine is but the first step toward eradicating the problem. The leaders who are responsible then need to be criminally indicted and subjected to trial by jury.

Similarly, researchers should be held criminally liable when scientific fraud and misrepresentation are proven. Their actions reflect the thinking and intent of knaves, not fools. These people know what they are doing. The due process of law is likely to uncover and judge the evidence of guilt or innocence more reliably and fairly than will the institutions of science and the professions that historically have resisted taking decisive action against the perpetrators.

Let’s step back to reflect on the biomedical research establishment’s current state of affairs, using three perspectives:

1. In a frequently cited 2005 Plos Medicine article, John Ioannidis concludes, “…for most study designs and settings, it is more likely for a research claim to be false than true. Moreover, for many current scientific fields, claimed research findings may often be simply accurate measures of the prevailing bias.”

2. In a 2009 Lancet article, Ian Chalmers and Paul Glaziou describe the “avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence.” For the >85% loss of the more than US$100 billion annual investment in biomedical research worldwide, they identify these four causes: (a) choosing the wrong questions for research; (b) doing studies that are unnecessary, or poorly designed; (c) failure to publish relevant research promptly, or at all; and (d) biased or unusable reports of research.

3. In a 2014 New York Times Sunday Review article, Michael Suk-Young Chwe suggests that the way to cope with the deserved lack of credibility of today’s science is to “look for help to the humanities, and to literary criticism in particular.” He argues that science cannot heal itself because of the “pride and prejudice” in its self-limited view of the world. He cites the need to question “the validity — of the fore-meanings dwelling within (oneself)” when interpreting text, as advocated by the German philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer in “Truth and Method.” Suk-Young Chwe concludes, “To deal with the problem of selective use of data, the scientific community must become self-aware and realize that it has a problem.”

As much as I wish that the biomedical research establishment could become so self-aware, I do not believe that will happen without much stronger incentives than have been delivered in the past 40 or so years since I have been tracking premeditated bias in its many forms (see my 2007 article — Monash Bioethics Review 2007; 26(1-2):24). The research establishment has demonstrated tenacity in hunkering down and going passive-aggressive when confronted by efforts to get it to clean up its act. I have noted that pointing out the systemic incentives to cheat merely serves first as an explanation, then as an excuse, and finally as justification.

As Meredith Wadman reports in her 2006 article “A Few Good Scientists,” the ethicist Arthur Caplan suggests a more measured approach than rejection of the entire body of commercially tainted biomedical research, lest “the search for the untainted investigator … become like Diogenes’ quest to find an honest man.” In my view, Caplan reflects the pervasive view among members of the research establishment that corrupt practices are inevitable and unavoidable — when push comes to shove, they will shield their colleagues.

For myself, I see no viable alternative to ferreting out and reporting premeditated bias — the extreme of which is outright falsification of data — committed by researchers who often have concomitant conflicts of interest that affect the reliability and validity of biomedical science. Should we give up and hope to escape becoming another iatrogenic morbidity or mortality statistic? No!

For this reason, I side with Richard Smith’s assessment: Scientific fraud should be made a criminal offense. The shock of jail time may signal to the scientific community that it has a problem that can’t be explained away or rationalized.

Do you agree with John Noble? Share your comments here.