August 25th, 2014

An Electrophysiology Service Diagnostic Conundrum

Seth Shay Martin, MD and James Fang, MD

A 57-year-old woman who is a retired speech therapist is seen on an inpatient electrophysiology (EP) service. She has a history of hypertension, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF), long-QT syndrome after ICD implantation, migraine headaches, anxiety, and major depression. For frequent paroxysms of AF with rapid ventricular response (RVR) associated with palpitations and dyspnea during the past 3 years, she failed a trial of sotalol (her QT interval was significantly prolonged) and did not tolerate Norpace (disopyramide).

She started flecainide during a hospitalization for AF with RVR a week ago, and her current rehospitalization is for the same problem. Following initiation of treatment with intravenous esmolol and amiodarone, she was transferred to the present EP service.

Notably, the patient had not been on systemic anticoagulation mainly because of a history of recurrent and unexplained falls that were described as classic “drop attacks.” The patient reported that she would suddenly become weak and fall to the ground while remaining conscious. The last fall occurred 5 days before transfer to the present EP service.

Upon arrival to the EP service, she had no localizing findings on physical examination. Inpatient ICD interrogation showed no arrhythmic event at the time of her last fall. With a monitoring zone 1 set at 190 beats per minute, there were 10 recorded episodes of AF with RVR; the longest lasted 1.3 minutes, and most lasted <30 seconds. The patient was atrial-paced 75% of the time with the device set at 75 bpm, likely to shorten the QT interval. An echocardiogram was normal, including normal left ventricular size and wall thickness with an LV ejection fraction estimated at 65% to 70%.

The patient underwent tilt-table testing, which provided evidence against neurally mediated (vasodepressor) syncope, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, or hypersensitive carotid sinus syndrome. Inpatient telemetry monitoring showed well-controlled heart rates on amiodarone and a beta-blocker. However, during inpatient observation, the patient intermittently experienced severe episodes of anxiety associated with spikes in blood pressure, from a normal baseline to 200–220 mm Hg systolic and 110–120 mm Hg diastolic. These episodes occurred multiple times daily.

Questions:

- What is at the top of your differential diagnosis?

- What additional information would you like to have?

- What further medical testing would change your management approach?

Response:

August 28, 2014

This case is very suspicious for a paroxysmal condition such as pheochromocytoma (pheo). The classic triad of headache, tachycardia, and diaphoresis should prompt a consideration for pheo, although the triad is sensitive but not specific. It’s important to note that hypertension in these cases may be paroxysmal or chronic; orthostasis may also be present, related to a “pressure-mediated” diuresis. Severe hypertension associated with anesthesia or other procedures may suggest pheo as well.

Pheo is a commonly considered but rarely diagnosed condition; some estimates suggest that only one in a few hundred evaluations is ever positive. Pheo may also present as a dilated cardiomyopathy and should be considered in cases when severe multidrug-resistant hypertension complicates a nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Pheo is one of several catecholamine-mediated conditions that produce reversible LV dysfunction; others include the cardiomyopathy of brain injury or death (usually encountered in neurology ICUs or during heart-transplant donor evaluation) and stress cardiomyopathy (e.g., Takotsubo).

I wonder if diaphoresis can be elicited by history; the autonomic nature of diaphoresis should always raise clinical suspicion for a significant cardiovascular condition. The optimal screening tests are debated, but most observers suggest some combination of a 24-hour urine collection for metanephrines and catecholamines or a plasma (fractionated) metanephrine level. Clinicians often obtain adrenal imaging or metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scanning, but the yields are low without pre-imaging laboratory testing. If screening lab findings are negative, some suggest obtaining the screening studies during a paroxysm. More-sophisticated tests — such as clonidine suppression, chromogranin A, and neuroendocrine studies — are rarely used. When the patient has a family history of multiple endocrine neoplasia, a more exhaustive diagnostic evaluation may be necessary.

I would consider using an alpha-antagonist, such as prazosin, for the acute management of this patient; phenoxybenzamine is the classically used alpha-antagonist, but it is long-acting and irreversible. Notably, initial use of beta-blockade can be disastrous (due to unopposed alpha activity) and should always be preceded by adequate alpha-blockade.

Follow-Up:

September 5, 2014

The patient was indeed diagnosed with a pheochromocytoma, confirmed biochemically and by imaging. Her plasma and urine metanephrine levels were markedly elevated:

- total plasma metanephrines 2779 pg/mL (reference range, <205)

- plasma normetanephrines 2648 pg/mL (reference range, <148)

- total urine metanephrines 4236 μg/24 hours (reference range, <832)

- urine normetanephrines 3929 μg/24 hours (reference range, <676)

A CT scan revealed a 3.1-cm x 2.9-cm mass in the right adrenal gland that was hyperenhancing and possibly centrally necrotic. The patient was prepared for surgery with standard therapies, including intravenous fluid administration, liberalization of dietary sodium, and oral phenoxybenzamine for alpha-blockade, titrated to the point of mild orthostasis with positional changes. She then underwent a laparoscopic right adrenalectomy, which was successful. She is faring well on outpatient follow-up: Her metanephrine levels normalized, and her symptoms improved.

August 21st, 2014

FDA Grants Apixaban Expanded Indication for Venous Thromboembolism

Larry Husten, PHD

The FDA today approved an expanded indication for the oral anticoagulant apixaban (Eliquis, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer). Apixaban will now be indicated for the treatment of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), and for the reduction in the risk of recurrent DVT and PE (collectively known as venous thromboembolism) after initial therapy. The supplemental new drug application was based on findings from the previously published AMPLIFY and AMPLIFY-EXT studies.

All three of the new oral anticoagulants — dabigatran (Pradaxa, Boehringer Ingelheim), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), and apixaban – have now gained both the VTE indication as well as the indication for stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (SPAF). Rivaroxaban and apixaban are also approved for DVT prophylaxis following hip- or knee-replacement surgery.

Both apixaban and rivaroxaban were studied using a single-drug approach for acute use in the hospital and for continued use afterwards. By contrast, dabigatran was studied in patients after they had received parenteral anticoagulants and is indicated for use following treatment with a parenteral anticoagulant for 5 to 10 days.

August 21st, 2014

The Niacin Controversy: What Do You Say to Your Patient?

Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, SM

This post is the fifth in our series “What Do You Say to Your Patient?” In this series, we ask members to share how they interpret a complex or controversial issue for patients. To review earlier posts, click

The following scenario stems from the controversial HPS2-THRIVE study published in The New England Journal of Medicine last month.

Your 62-year-old male patient who has been on statin therapy for 10 years comes in to see you.

For the past five years he has been taking atorvastatin 80 mg and niaspan 2g once daily with no discernible side effects. His LDL is 90 mg/dl, HDL is 42 mg/dl, and triglycerides are 120 mg/dl. He had a PCI 12 years ago, but has had no procedures since.

Your patient recently read in the paper that there is new information about niacin. He asks if there is anything he should know – and whether his regimen should be changed.

What do you tell him?

August 19th, 2014

Increased Cardiac Risk Linked to Clarithromycin

Larry Husten, PHD

Acute use of the popular macrolide antibiotic clarithromycin has been linked to a small but significant increase in cardiac death. In a report in the BMJ, researchers in Denmark analyzed the effects over a 14-year period of the acute use of penicillin V, roxithromycin, and clarithromycin.

Earlier research raised concerns that marcrolide antibiotics in general, and erythromycin and azithromycin in particular, might prolong the QT interval and increase the risk for fatal arrhythmias.

In the new study, clarithromycin was associated with a significant increase in the rate of sudden cardiac death compared with the other two antibiotics: 5.3 per 1000 person years for clarithromycin versus 2.5 per 1000 person-years for penicillin V and roxithromycin. After adjustment for baseline differences, the result remained significant (rate ratio, 1.76, CI 1.08-2.85). The authors calculated that compared with penicillin V, clarithromycin resulted in an absolute risk difference of 37 cardiac deaths per million courses of clarithromycin (CI 4-90). It should be noted, however, that the absolute number of events was quite low: in total there were 285 cardiac deaths that occurred during ongoing use of the study drugs, 18 of which occurred during use of clarithromycin.

The study raised the possibility that the increased risk was stronger in women than in men. “This finding is consistent with female sex being a known risk factor for drug induced cardiac arrhythmia in general and macrolide induced arrhythmia in particular,” the authors wrote.

The authors discussed the practical implications, if any, of their research:

On the one hand, the absolute risk is small, so this finding should probably have limited, if any, effect on prescribing practice in individual patients (with the possible exception of patients who have strong risk factors for drug induced arrhythmia). On the other hand, clarithromycin is one of the more commonly used antibiotics in many countries and many millions of people are prescribed this drug each year; thus, the total number of excess (potentially avoidable) cardiac deaths may not be negligible. These factors need to be considered when assessing the overall benefit/risk profile of macrolides (clarithromycin specifically)…

August 19th, 2014

Do Patients Really Have to Fast Before Lipid Testing?

Sripal Bangalore, MD, MHA

CardioExchange’s Harlan M. Krumholz interviews Sripal Bangalore about his research group’s study of the prognostic value of non-fasting lipid panels. The study is published in Circulation.

Krumholz: Please briefly describe the high points of your article.

Bangalore: We questioned the value of “fasting” lipid panel measurement, given that people spend very little of their everyday lives fasting. Using NHANES-III data, we found that in terms of predicting long-term all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, fasting LDL was no better than non-fasting LDL. This also held true for total cholesterol and for triglycerides, thereby challenging the age-old practice of requiring people to fast before a lipid panel.

Krumholz: How does what you found align with prior reports?

Bangalore: Our report is aligned with prior reports that show similar results for triglycerides. Our findings confirm the data on triglycerides and expand the evidence base to LDL cholesterol and total cholesterol.

Krumholz: Non-fasting LDL may be predictive — but how should we think about it with regard to risk scores? Does it matter?

Bangalore: If one were to base it on the 2013 ACCF–AHA guidelines, the definition of 3 out of the 4 statin-benefit groups is based on LDL cholesterol levels. Risk scores are important, but the baseline LDL cholesterol level is also important.

Krumholz: What are you doing with your patients?

Bangalore: I am comfortable using a non-fasting lipid panel to make treatment decisions. It is convenient for the patient, and the prognostic value, as we show, is no different than that of the fasting lipid panel.

Krumholz: Finally, for non-fasting LDL, are there any calibration issues?

Bangalore: Prior studies have shown that LDL-cholesterol variability between fasting and non-fasting status is minimal, usually less than 10%. One would therefore not expect fasting lipid status to yield a significant reclassification of patients.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

Do you think the age-old practice of making patients fast for a lipid panel is on its way out?

August 18th, 2014

Selections from Richard Lehman’s Literature Review: August 18th

Richard Lehman, BM, BCh, MRCGP

CardioExchange is pleased to reprint this selection from Dr. Richard Lehman’s weekly journal review blog at BMJ.com. Selected summaries are relevant to our audience, but we encourage members to engage with the entire blog.

NEJM 14 August 2014 Vol 371

Association of Urinary Sodium and Potassium Excretion with Blood Pressure (pg. 601): The usual wisdom about sodium chloride is that the more you take, the higher your blood pressure and hence your cardiovascular risk. We’ll begin, like the NEJM, with the PURE study. This was a massive undertaking. They recruited 102 216 adults from 18 countries and measured their 24 hour sodium and potassium excretion, using a single fasting morning urine specimen, and their blood pressure by using an automated device. In an ideal world, they would have carried on doing this every week for a month or two, but hey, this is still better than anyone has managed before now. Using these single point in time measurements, they found that people with elevated blood pressure seemed to be more sensitive to the effects of the cations sodium and potassium. Higher sodium raised their blood pressure more, and higher potassium lowered it more, than in individuals with normal blood pressure. In fact, if sodium is a cation, potassium should be called a dogion. And what I have described as effects are in fact associations: we cannot really know if they are causal.

Urinary Sodium and Potassium Excretion, Mortality, and CV Events (pg. 612): But now comes the bombshell. In the PURE study, there was no simple linear relationship between sodium intake and the composite outcome of death and major cardiovascular events, over a mean follow-up period of 3.7 years. Quite the contrary, there was a sort of elongated U-shape distribution. The U begins high and is then splayed out: people who excreted less than 3 grams of salt daily were at much the highest risk of death and cardiovascular events. The lowest risk lay between 3 g and 5 g, with a slow and rather flat rise thereafter. On this evidence, trying to achieve a salt intake under 3 g is a bad idea, which will do you more harm than eating as much salt as you like. Moreover, if you eat plenty of potassium as well, you will have plenty of dogion to counter the cation. The true Mediterranean diet wins again. Eat salad and tomatoes with your anchovies, drink wine with your briny olives, sprinkle coarse salt on your grilled fish, lay it on a bed of cucumber, and follow it with ripe figs and apricots. Live long and live happily.

Global Sodium Consumption and Death from CV Causes (pg. 624): It was rather witty, if slightly unkind, of the NEJM to follow these PURE papers with a massive modelling study built on the assumption that sodium increases cardiovascular risk in linear fashion, mediated by blood pressure. Dariush Mozaffarian and his immensely hardworking team must be biting their lips, having trawled through all the data they could find about sodium excretion in 66 countries. They used a reference standard of 2 g sodium a day, assuming this was the point of optimal consumption and lowest risk. But from PURE, we now know it is associated with a higher cardiovascular risk than 13 grams a day. So they should now go through all their data again, having adjusted their statistical software to the observational curves of the PURE study. Even so, I would question the value of modelling studies on this scale: the human race is a complex thing to study, and all models need to be taken with a pinch of salt.

JAMA Intern Med August 2014 Vol 174

Prevalence of Anginal Symptoms and Myocardial Ischemia and Their Effect on Clinical Outcomes in Outpatients With Stable CAD (OL): It is most regrettable that the leading journals have taken to publishing interesting papers during the month of August. Just when you think you can catch up with long neglected projects while everybody is away, or do a bit in the garden, along comes a whole batch of papers that really call for mental involvement. Here, on top of the NEJM salt papers, is a pretty amazing study from the Prospective Observational Longitudinal Registry of Patients With Stable Coronary Artery Disease (CLARIFY) registry. Do I really want to spend a sleepy summer afternoon going through this for your benefit? No, but I will; and then I intend to take a week’s break. The really startling finding here is that if you have known coronary disease accompanied by silent myocardial ischaemia, your outlook is actually better than if you have coronary disease without silent ischaemia. You can understand why these silently ischaemic people do better than those with overt angina, but it’s more difficult to understand why they do better than others with coronary disease and no reduction in perfusion. Perhaps it’s to do with ischaemic preconditioning. This was a complex cohort on a lot of preventive medication, so if you really want to make deductions, you too will have to sacrifice part of a summer’s day.

Lancet 16 August 2014 Vol 384

Implant-Based Multiparameter Telemonitoring of Patients with Heart Failure (IN-TIME) (pg. 583): Here is a heart failure trial, which illustrates everything that’s wrong with heart failure trials: and yet I quite like it. “The funder assisted in study design, data collection, data analysis, and preparing this report. They had no role in data interpretation.” Given the first sentence, can you believe the second? The funder, Biotronik SE & Co. KG. was of course testing its own product—a telemonitor implanted within a Lumax dual-chamber implantable cardioverter-defibrillators or cardiac resynchronization therapy device. The mean age of the participants was at least 10 years younger than the average patient with heart failure, and the unwieldy composite end point was all-cause death, overnight hospital admission for heart failure, change in New York Heart Association class, and change in patient global self-assessment. Half of the patients were blinded, but the assessors were not. What’s not to hate? And yet the results are important and believable. Ignore the messy composite end point: the fact is that 10 versus 27 patients died during follow-up of one year. And this was achieved with minimal effort: these devices didn’t go off all the time, creating anxiety and work for everybody. On average, patients in the active group only received two phone calls during the study. So having devices that report events is probably genuinely useful for preventing serious tachyarrhythmias, pacing malfunction, and inappropriate shock therapy, and can halve mortality. It’s good to know there are replication studies underway, as Martin Cowie’s sensible editorial describes.

“Blood pressure lowering treatment based on cardiovascular risk: a meta-analysis of individual patient data.” (pg. 591): I rubbed my eyes. Grails don’t come much holier than this. For 10 years, we’ve realised that statin treatment is not about lipids, but about cardiovascular risk reduction. And yet we’ve gone on treating “hypertension” as if it was a disease in itself. I had almost given up hope that hypertensionologists would realize that the numbers needed to treat to prevent events in people with elevated BP depended on their total cardiovascular risk. And here it is, nicely illustrated in a meta-analysis of 11 randomized trials. “These results support the use of predicted baseline cardiovascular disease risk equations to inform blood pressure lowering treatment decisions.” As people with high blood pressure constitute the largest group of symptomless attenders in primary care, this will require little short of a revolution. Bring it on. I look forward to the day when nobody takes blood pressure lowering medication without a reasonable idea of the benefit (or harm) it may bring for them personally. This could be the most important paper for general practice to come out in the last 10 years.

Bivalirudin vs. Heparin in Patients Planned for PCI (pg. 599): Now that I have a small job with the UK Cochrane collaboration, I read more meta-analyses than I have hot dinners, by a factor of about ten. Mission fatigue can creep in, but here is another meta-analysis that restores the will to fight. Bivalirudin costs several hundred times as much as heparin. But it is widely used in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Randomized trials have failed to show a significant difference between the two. But if you combine data from all of them, you discover a higher rate of myocardial infarction and stent thrombosis in patients given bivalirudin. In most situations, this is not offset by the slightly lower risk of bleeding. The older, much cheaper, drug is simply better.

The BMJ 16 August 2014 Vol 349

Impact of Centralizing Acute Stroke Services in English Metropolitan Areas on Mortality and Length of Hospital Stay: The British Medical bit consists of a study of the impact of centralising acute stroke services in English metropolitan areas on mortality and length of hospital stay. This is a before and after study in London and Manchester. Make what you will of it: the differences are small and might have happened anyway. The authors use it to support centralization. Why am I not surprised?

August 18th, 2014

An Expert’s Perspective: Why Salt Is Not Like Tobacco and Why Guidelines Are Tricky

Larry Husten, PHD

At the center of this week’s renewed debate on salt was Salim Yusuf, the longtime influential and occasionally controversial cardiology researcher and clinical trialist based at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. I spoke with Yusuf before the publication of the New England Journal of Medicine papers, which include his own two papers from the PURE study.

Yusuf was troubled by the tone of some of the salt debate. He’s no stranger to scientific controversies and intense disagreement, but “scientific criticism is one thing, personal attack on those who hold a different viewpoint is another,” he said. Because he and others have presented data that suggest that moderately high levels of sodium may not be as bad as some had thought, and that very low levels of sodium may actually be harmful, “we’ve come under direct attack.”

Yusuf wanted to emphasize that the PURE findings should by no means be interpreted as suggesting that there is no relationship between salt and blood pressure, or that elevated blood pressure due to salt is never harmful. “Our data don’t contradict that there is an association between salt and blood pressure,” but, he points out, the relationship is not a simple linear relationship.

He therefore disagrees with some of the details of the accompanying NEJM paper from NUTRICODE, which calculates that each year there are 1.65 million cardiovascular deaths that can be attributed to high sodium consumption. The true number is more likely to be less than half a million, and this fits in with the sensitivity analyses presented in the paper by Dariush Mozaffarian, though these are not generally noticed or publicly discussed.

Surrogates and Sodium, Diet and Tobacco

“We know from a ton of data in cardiovascular disease that you can’t totally trust surrogate outcomes to make clinical decisions,” said Yusuf. He cited the recent ACCORD trials conducted by the NHLBI as only the most recent demonstration of this phenomenon. In that study lowering glucose or lowering blood pressure (by a rather large degree) did not lead to a significant reduction in cardiovascular disease outcomes.

But the low-salt advocates “believe that blood pressure is an incontrovertible surrogate, and we know that is not so.” Based on this belief, “they’re going after salt as the next tobacco.” But salt, said Yusuf, is not tobacco. “It’s not like smoking, where the optimal number is zero.”

“People forget that sodium is an essential nutrient,” required in every single cell in the body. “There will have to be some point where very low sodium is harmful.” He compared sodium to vitamins: “we know that supplementing vitamins well beyond an appropriate amount does no good and may even do harm. Equally, low levels of vitamins cause disease and so there is an optimal range for most nutrients that are key to normal physiology.”

The Responsibilities of Guideline Authors

Guidelines, especially national policy guidelines that make huge impacts on large populations, need to be based on firm evidence, said Yusuf: “If we get it wrong then we really harm a lot of people.” He compared the salt recommendations with the push some decades ago to reduce all kinds of fats and replace it with carbohydrates. The approach of recommending a reduction in all fats (not just saturated or trans) and replacing it with more carbohydrates is now having to be reconsidered and this may have contributed to the obesity and diabetes epidemics. “This is an example of how not getting policy right can have negative consequences.”

But also, said Yusuf, “think of the wasted energy. You can’t go to the lay public and say, ‘Do a lot of things, especially extreme changes to improve your life.’ You can only do two or three things. Your messaging has to be parsimonious.” Similarly, “is it wise to go to the government and ask them to legislate many things? You have to choose the two or three that are the most important and for which we have the most evidence.”

“In the end there are only a few public health policies on diet and lifestyle that we can recommend as a society in order to have credibility and so we have to choose them very carefully and focus on the ones for which we have the best evidence and those which are most feasible.”

In addition, said Yusuf, it is important that when new evidence emerges, guidelines should be re-evaluated objectively “rather than people or organizations digging in, and refusing to consider new evidence even when it may challenge one’s own thinking. Policy must be based on reliable evidence and not on personal positions. The last IOM report was an exercise that was laudable in that, under difficult circumstances, the committee did a fair job in pointing out what was known and areas that needed research. In the last few years, the guidelines on sodium have changed from targets as low as 1500 mg per day to about 2300 (IOM) or 2400 mg/day (NHLBI), and this means that despite the pressure, the new evidence is having an impact. A lot of new information has now become available since the IOM report and so it may be timely to reconvene a group of wise and unbiased individuals, who have not taken firm positions, by the IOM or by a global organization such as the WHO or the WHF, and re-examine current recommendations. People who have a dog in the fight, including me, can provide evidence but should have no role in formulating the policy recommendations. It should be done by those who have no professional or financial conflicts.”

August 18th, 2014

New Analysis of Old Study Fuels Debate Over Blood Pressure Guidelines

Larry Husten, PHD

In the last year new guidelines relating to cardiovascular disease have been the subject of intense criticism and debate. The status of the blood pressure guidelines has been particularly contentious, since several different groups have published contradictory guidelines, while several authors of the most prominent group, the Eighth Joint National Committee, published an impassioned dissent from their own published guideline. Many hypertension experts have taken aim at the change in therapeutic target for systolic blood pressure in patients age 60 or older, from 140 mm Hg to 150 mm Hg.

In an attempt to determine the optimal blood pressure for patients age 60 or older, Sripal Bangalore and colleagues performed a post-hoc analysis of 8,354 patients who participated in the INVEST trial, who were age 60 or older, and who had a baseline systolic blood pressure greater than 150 mm Hg. They divided these patients into three groups: those who reached blood pressure levels below 140 mm Hg (group 1), those who reached blood pressure levels between 140 and 149 mm Hg (group 2), and those who reached blood pressure levels 150 mm Hg or higher (group 3).

In their paper published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, the authors performed several analyses of the data. In their first analysis, which did not attempt to adjust for baseline differences in the three groups, a primary endpoint event (death, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke) occurred in 9.36% of patients in group 1, 12.71% of patients in group 2, and 21.32% of patients in group 3 (p<0.0001).

The investigators then adjusted for multiple differences between the groups. They calculated that when compared to group 1, patients in group 2 did not have a significant increase in the primary endpoint, but they did have significant increases in risk for cardiovascular mortality, total stroke, and nonfatal stroke. Compared to patients in group 1, patients in group 3 had a significant increase in the risk of a primary outcome event, as well as significant increases in risk for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, total MI, nonfatal MI, total stroke, and nonfatal stroke.

The authors said their findings re-affirm the more stringent blood pressure target of 140 mm Hg in this population and these results should be used to inform the debate over the new guidelines. This position received an endorsement from the presidents of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, Patrick O’Gara and Elliott Antman. They released the following statement:

“This study supports the concerns raised by many stakeholders, including the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association and a number of the individual members of the ‘JNC 8’ panel (Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(7):499-503.), about the panel’s 2013 recommendations to raise blood pressure targets in older patients. This new research suggests that raising the threshold for treatment of hypertension in patients 60 years of age or older with coronary artery disease may be detrimental to the best interest of patients and the public. It underscores ongoing concerns about adopting the unofficial 2013 targets as proposed by the panel originally appointed to write JNC 8. The ACC and AHA, working with the NHLBI, are in the process of assembling the writing panel that will evaluate evidence from a variety of sources and provide a comprehensive update of the hypertension guideline.”

But this view differs sharply from an accompanying editorial by Alan Gradman.

It is important to recognize that these results cannot be used as evidence against the JNC 8 panel’s selection of 150 mm Hg as the threshold for treatment. All patients in the analyzed cohort entered INVEST with an SBP of >150 mm Hg, and all would have been treated according to the new panel guidelines. Although thresholds for treatment and treatment targets are often thought of as identical, they are not….

In effect, the authors have compared the prognosis of “responders” to “nonresponders,” using the post-randomization variable of achieved on-treatment BP as a measure of response. There is considerable evidence that response to treatment is itself a function of patient characteristics, known or unknown, that may independently influence prognosis.”

Gradman calls for new trials to help resolve these problems, but “in the absence of such data, and given the depth and duration of this controversy, it is clear that there is no right answer.”

Sripal Bangalore sent the following response to the editorial:

The editorial is correct in a largely puristic viewpoint. However, if one were to base guidelines only on RCT evidence all our guidelines would have been only a couple of pages in length. For example, 13.5% of STEMI guideline recommendations are based on RCT data. I am all for RCTs to drive our recommendations, but in the absence of that, we have to take the totality of evidence to make a rational decision.

The evidence for <150 is based on two small RCTs, both of which had serious methodological limitations. One trial was grossly underpowered and the second trial showed interaction such that there was potential benefit for those <75 years (vs. >=75 years) with targets <140 mm Hg. In my viewpoint, this hardly qualifies as ‘robust’ evidence for a target of <150 mm Hg.”

Harlan Krumholz offered the following comment about the controversy:

Unfortunately this study is not designed to test optimal target levels. It may be reflecting adherence rates among the subjects, a characteristic known to affect outcomes even among those were taking placebo. It would be a shame if this article was considered to be strong evidence in the current public dialogue about target levels for blood pressure.”

August 18th, 2014

Radial Access for PCI in Women: A Registry-Based Randomized Trial

Sunil Rao, MD, Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, SM and John Ryan, MD

CardioExchange’s Harlan M. Krumholz and John Ryan interview Sunil V. Rao, lead author of SAFE-PCI for Women, a registry-based randomized trial of a radial versus a femoral approach to PCI. The study is published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

Krumholz and Ryan: Please describe your study and its major findings.

Rao: We conducted a randomized trial comparing a radial approach with a femoral approach in women undergoing cardiac catheterization (with the possibility of PCI) or scheduled PCI. Our rationale for the study was that women undergoing invasive procedures have a higher risk for bleeding than men, as well as a greater challenge in completing radial procedures, given smaller radial artery diameter and spasm. We had two primary endpoints: an “efficacy” endpoint (a composite of BARC* type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding or vascular complications requiring intervention) and a “feasibility” endpoint (accounting for access-site crossover). This was a “registry-based trial”: The sites were identified through the ACC NCDR CathPCI registry, and a large proportion of the data collection was through the registry.

The trial was stopped early because the event rate was much lower than expected. Our primary-analysis cohort consisted of women who underwent PCI, a subgroup of all women who were randomized. Interestingly, the primary efficacy endpoint showed no significant difference between radial and femoral access among women who underwent PCI; however, among all women who were randomized (including those who underwent just diagnostic coronary angiography), radial access was associated with a significant 60% lower incidence of the primary efficacy endpoint. In both cohorts, the rate of access-site crossover was significantly higher among women assigned to radial than to femoral access.

Krumholz and Ryan: How will this study affect your practice?

Rao: Our practice is already “radial first,” so this study bolsters our confidence in the safety of the radial approach in a high-risk population such as women. One can look at this trial from two perspectives: The purist would say that the trial is negative; in the primary-analysis cohort of women undergoing PCI, radial access did not reduce complications but did require operators to bail out to femoral access. The pragmatist would say that the PCI cohort is a subgroup of the overall randomized population and is underpowered to detect a difference. The directionality of the effect in the PCI cohort favors a radial approach, and in the larger sample size of all women who were randomized, the radial approach showed a significant reduction in bleeding and vascular complications, albeit at the higher rate of femoral crossover. The interaction term for the primary efficacy endpoint between patients who underwent diagnostic catheterization versus PCI was not significant, indicating a consistent effect across both cohorts.

Krumholz and Ryan: It is a “pragmatic trial” — please define that for our readers.

Rao: I think the meaning probably differs for different people. From our perspective, it was pragmatic because we had a system for site identification and data collection that increased the efficiency of the trial. Let me explain: Traditionally, when we identify study sites, a questionnaire is sent to sites’ principal investigators (PIs) asking questions about their practice, the number of cases they perform, the kinds of patients they see, and so on. This is highly subject to recall bias. For the SAFE PCI for Women trial, we needed sites that truly had expertise with a radial approach, so instead of relying on PI recall, we queried the CathPCI registry and identified sites that were performing radial procedures frequently. These sites formed our initial study sites. With respect to data collection, the study sites were already submitting procedure-related data to the CathPCI registry, so a large proportion of the registry data auto-populated the trial case-report form. This significantly reduced the workload for the site’s study coordinators. A clinical-events committee adjudicated all endpoint data.

Krumholz and Ryan: You built the trial to leverage the NCDR database. How did you do that, and how did it affect cost? What was the cost per subject, if you don’t mind sharing?

Rao: The software interface that connected the CathPCI registry with the case-report form, called the National Cardiovascular Research Infrastructure, was funded by the NHLBI. Bob Harrington MD, David Kong MD, and Brian McCourt led the effort at the Duke Clinical Research Institute, collaborating closely with the American College of Cardiology. We don’t have data on cost per subject, but the total budget for this trial — which randomized 1787 women, had 30-day follow-up, and included event adjudication — was $5 million.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

How do the findings from Dr. Rao’s trial affect your perspective on radial access for PCI in women?

*BARC = Bleeding Academic Research Consortium

August 18th, 2014

Disparities in Healthcare: Young Women Continue to Fare Worse than Men after an AMI

Aakriti Gupta, MD

CardioExchange recently had the pleasure of discussing with Dr. Aakriti Gupta the findings of her study “Trends in Acute Myocardial Infarction in Young Patients and Differences by Sex and Race,” published recently in JACC. Here is her analysis of the problems as well as her proposed solutions.

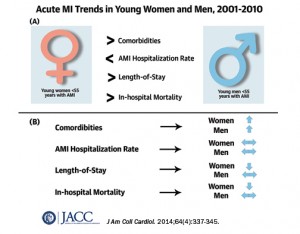

Even though more than 30,000 women less than 55 years of age suffer from acute myocardial infarction (AMI) every year in the US alone, young women remain a vulnerable, yet understudied group with worsening cardiac risk profiles and worse outcomes as compared with men. Our study, published recently in JACC, shows that these healthcare disparities in cardiovascular disease are persistent, although have a favorable trend. Three points about AMI in the young to take away from this study are as follows:

Unlike their Medicare-aged counterparts who showed a 20% decline in hospitalization rates for AMI in a previous study, both women and men with AMI younger than 55 years old showed no significant change.

Unlike their Medicare-aged counterparts who showed a 20% decline in hospitalization rates for AMI in a previous study, both women and men with AMI younger than 55 years old showed no significant change.- Young women with AMI, and black women in particular, have higher disease burden including hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes. Both young women and men showed worsening trends for these co-morbidities through the decade.

- Although impressive declines in in-hospital mortality were noted for women and not for men, significant excess mortality remained for women through each of the 10 years included in our study.

Next Steps:

- Better Data Collection:

To better understand healthcare disparities, collection of high-quality data is key. An American Heart Association national survey showed that only 18 percent of hospitals in 2011 were collecting race, ethnicity, and language data at the first patient encounter. Good quality clinical data is imperative to quantify the contribution of social, economic, biological and genetic factors responsible for healthcare gaps based on gender and race. Such efforts would help guide redirection of our resources appropriately.

- Spread of awareness among public, patients, physicians and policymakers alike:

Several campaigns including the Go Red for Women and The Heart Truth were launched in the previous decade to increase awareness of cardiovascular disease prevention among women. A subsequent survey showed that only half of the young women included in the survey were aware of cardiovascular disease as the leading cause of death in 2009. This issue is even more relevant at the global level, as I imagine the situation may be worse.

- Role of Health Policy:

With expansion of insurance coverage per the Affordable Care Act, there may be several opportunities to focus on health care disparities. In particular, expanded payments for primary care can really benefit Medicaid beneficiaries, many of whom are minorities. In the face of worsening trends of co-morbidities including diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidemia in the young, there is tremendous scope for improved primary prevention in this segment of the population.

- Better Risk Stratification Tools and Implementation in Primary Care:

It is concerning that prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors like hypertension, dyslipidemia, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes was much higher in women through the decade. As pointed out by Drs. Shaw and Butler in the accompanying editorial, risk-based detection tools should form the core of targeted preventive strategies in cardiovascular prevention. Further efforts in this direction could be very high-yield for cardiovascular prevention.

Finally, I would emphasize that there have been substantial mortality declines noted among young women (30% decline from 2001 to 2010). This achievement may be attributed to several positive developments in the past decade including improved awareness, better access to care, better preventive strategies, and more coronary revascularization procedures. Having said that, women continue to have significant excess mortality after AMI as compared with men. Our first step toward reducing health disparities and achieving health equity should be to spread the message.