October 13th, 2014

Selections from Richard Lehman’s Literature Review: October 13th

Richard Lehman, BM, BCh, MRCGP

CardioExchange is pleased to reprint this selection from Dr. Richard Lehman’s weekly journal review blog at BMJ.com. Selected summaries are relevant to our audience, but we encourage members to engage with the entire blog.

Lancet 11 October 2014 Vol 384

Once-Weekly Dulaglutide vs. Once-Daily Liraglutide in Metformin-Treated Patients with Type 2 Diabetes (pg. 1349): If I were Oscar Wilde, I would stretch my legs and declare, “My dear, if I have to read another of these trials I shall simply die of tedium.” The object of despair is called: “Once-weekly dulaglutide versus once-daily liraglutide in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes (AWARD-6): a randomised, open-label, phase 3, non-inferiority trial.” Spending on type 2 diabetes in the UK is rising disproportionately, driven by incretin mimetic drugs with unknown long term effects. So here is a single blinded trial run by Eli Lilly to test its me-too contender. The language used is rather strange. “An independent external committee adjudicated deaths and non-fatal cardiovascular adverse events in a masked manner, with prespecified event criteria based on the preponderance of the evidence and clinical knowledge and experience.” What does that actually mean? And if that is obscure, look at the conclusion, presented in statistic-wonkese: “Once-weekly dulaglutide is non-inferior to once-daily liraglutide for least-squares mean reduction in HbA1c, with a similar safety and tolerability profile.” Delve deeper those who will: for my part I shall yawn and send for a good cigar, a glass of hock and seltzer, and a green carnation for my buttonhole.

The BMJ 11 October 2014 Vol 349

Variation in Patients’ Perceptions of Elective Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Stable Coronary Artery Disease: Speaking of informed choice before procedures, how many patients accurately perceive the benefits of elective percutaneous coronary intervention in stable coronary artery disease? I don’t know the answer for British patients, but John Spertus and his team have tried to find out about Americans. The answer, of course, is not very many: 90% thought that the procedure would extend life and 88% thought it would prevent a future heart attack. So much for the public understanding of evidence based medicine versus the vested interests of interventional cardiologists.

October 13th, 2014

Heart Failure Readmissions: Neighborhood Factors Matter, Too

Behnood Bikdeli, M.D.

For two decades, investigators have been studying the association between neighborhood characteristics and cardiovascular disease. A landmark study from 2001 showed that living in a socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhood was associated with higher incidence of coronary artery disease. Several studies have also shown an association between neighborhood characteristics, most notably the socioeconomic status (SES) and outcomes of patients with heart failure (HF). Previous studies, however, have not clarified whether neighborhood factors are merely a proxy for individual-level factors or are independent predictors of HF outcomes.

My colleagues and I recently published a study of the association between neighborhood socioeconomic status (SES) and outcomes among 1557 patients from the Telemonitoring to Improve Heart Failure Outcomes (Tele-HF) trial. We found a statistically significant association between low neighborhood SES and higher odds of hospital readmission in patients with HF — an association that, notably, persisted after adjustment for a wide array of individual-level factors such as demographics, comorbidities, therapies, and even individuals’ SES.

I believe that the findings from our study and several others collectively suggest that although individual factors (e.g., patient factors, individuals’ SES, quality of care) and neighborhood factors (e.g., neighborhood SES) might overlap, each of those factors also has some independent correlation with disease incidence and outcomes (see figure by clicking here).

To improve disease outcomes, we may need to focus both on individual factors and on modifiable neighborhood factors, an effort that could require partnership with local governments, business owners, and (most important) residents. It will be crucial to determine whether modifying neighborhood characteristics (e.g., walkability, better access to healthy food, and reducing noise or air pollution) translates into better disease outcomes.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

Have you encountered patients whose place of residence affected their treatment plan, course of therapy, or access to care?

October 13th, 2014

First Drug-Coated Balloon Approved by FDA for Leg Blockages

Larry Husten, PHD

The FDA today announced that it had approved for use in the U.S. the first drug-coated angioplasty balloon catheter to re-open blocked arteries in the superficial femoral and popliteal arteries. The Lutonix 035 Drug Coated Balloon Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty Catheter (Lutonix DCB) is manufactured by CR Bard and has been available in Europe since 2012.

“Peripheral artery disease can be quite serious. Preventing further blockage of arteries is just as important as removing the initial blockage” said William Maisel, the deputy director for science and chief scientist in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, in an FDA press release. “The clinical data show that Lutonix DCB may be more effective than traditional balloon angioplasty at helping to prevent further blockage in the artery.”

The Lutonix DCB “is a new first-line therapy for treating blockages, without closing the door to other treatment options down the road,” said Harvard University’s Kenneth Rosenfield, in a CR Bard press release. Rosenfield said the new device can also be used “to complement existing therapy options.”

Rosenfield was the principal investigator of the LEVANT 2 pivotal study which randomized 101 patients to the Lutonix DCB or conventional balloon angioplasty. At six months, fewer than half the patients treated with conventional therapy did not require additional treatment for their peripheral disease. By contrast, 71.8% of patients in the Lutonix DCB did not need additional treatment.

The FDA is requiring the manufacturer to perform two post-approval studies. The first will monitor the long-term safety and effectiveness of the device in 657 patients. The second is a randomized trial designed to assess the safety and efficacy of the device in women.

Rick Lange was a member of the FDA advisory panel that recommended approval of the Lutonix DCB earlier this year. He noted that the panel wrestled with some difficult issues, including the apparent lack of benefit for women in the trial. But the panel voted unanimously to recommend approval, said Lange, in the belief that the device was both safe and at least as effective as conventional therapy. “It’s a little easier than a stent since you’re not leaving anything inside,” he said.

October 9th, 2014

Why Bad Doctors Are Like Bad Writers: The Curse Of Knowledge

Larry Husten, PHD

Steven Pinker, the Harvard psychologist and best-selling author, has a wonderful essay in the Wall Street Journal about why smart people are so often bad writers. Although the essay doesn’t touch on the subject of doctor-patient communication, every single word applies to doctors and the way they communicate (or fail to communicate) with their patients.

Here’s the core of Pinker’s argument. Read the rest of it. And if you’re a doctor and you don’t see how this is relevant to how you communicate with your patients then you need to think again.

“In explaining any human shortcoming, the first tool I reach for is Hanlon’s Razor: Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity. The kind of stupidity I have in mind has nothing to do with ignorance or low IQ; in fact, it’s often the brightest and best informed who suffer the most from it.”

Pinker goes on to describe a professor giving a lecture on a recent breakthrough in his field to a large general audience. “He launched into a jargon-packed technical presentation that was geared to his fellow molecular biologists, and it was immediately apparent to everyone in the room that none of them understood a word and he was wasting their time. Apparent to everyone, that is, except the eminent biologist… Call it the Curse of Knowledge: a difficulty in imagining what it is like for someone else not to know something that you know.”

From the archives of the New England Journal of Medicine, here are two more worthwhile perspectives about doctors abusing language:

In 1975 Michael Crichton, the best-selling novelist and MD, neatly dissected the various forms of language abuse he found in, of all places, NEJM itself.

In 1979 Nicholas Christy wrote about Medspeak.

What do you think?

October 9th, 2014

FDA Panel Gives Cautious Endorsement to Novel Boston Scientific Device

Larry Husten, PHD

The FDA’s Circulatory System Devices advisory panel gave an extremely cautious endorsement on Wednesday to Boston Scientific’s Watchman device, a novel catheter-delivered left atrial appendage closure device for people with atrial fibrillation. They signaled that although they thought the device should be made available they also thought that there should be significant restrictions on its use.

The panel wrestled throughout the day with a fundamental problem: combined data from the two clinical trials, PROTECT AF and PREVAIL, showed clearly that Watchman was not equivalent to warfarin for the chief indication of stroke reduction in the study population. Furthermore, in clinical trials patients who received the Watchman were compared to patients taking warfarin. But there was a strong sentiment among panel members that the device should be available only to AF patients who are eligible for warfarin but don’t want to take it and, perhaps also, for patients who are not eligible for warfarin therapy. The problem, of course, is that neither of these patient groups was studied in the clinical trials.

Panel members delivered a complex message to the FDA regulators who will ultimately decide the fate of the device. They unanimously agreed that the device was safe, but split 6-6 on the question of efficacy. The panel’s chair, Richard Page, broke the tie with a no vote. On the final and third vote on whether the risks outweighed the benefits, 6 panel members voted yes, 5 no, and 1 (former ACC president Ralph Brindis) abstained. But panel members were highly vocal in stating that their vote did not indicate in any way support for the actual proposed indication for stroke reduction in warfarin-eligible patients.

Panel members said that they wanted the FDA to craft a narrow and highly restricted indication. Summarizing the panel’s sentiment, Page said it was incumbent on the sponsor and the FDA to maximize the degree to which only appropriate patients would get the device. “It’s not an alternative to every warfarin eligible patient,” he said. Panel members and FDA staff discussed several possible measures to achieve this goal, including patient guides, a controlled rollout with limited device availability, the requirement that an independent physician sign off before the procedure, and a national registry.

Bram Zuckerman, the director of the FDA’s Division of Cardiovascular Devices, agreed that “if approved it would require continuous monitoring of appropriate use.”

Panel members were acutely aware of their difficult position. Said Page: “The problem is that the proposed indication — prevention of thromboemboslim — is no longer realistic, so a likely real world use is for the device to be used in a different population and not as a replacement for warfarin.” Patricia Kelly suggested that the Watchman “could be offered to patients who don’t want to take warfarin, but they would need to be told that it is not considered equivalent to warfarin.”

The panel struggled with the differences between first-line therapy and second-line therapy as well as warfarin-eligible, warfarin-intolerant, and people who just don’t want to take warfarin. Said Page: “Every patient in Watchman clinical trials was warfarin eligible but now the only possible indication may be for warfarin-ineligible patients.”

David Kandzari said that even a “second line indication would be hard when both primary efficacy endpoints were missed.” Page noted that it would be difficult to make sure that it was available only as a second line.

Given the failure of the trials to demonstrate noninferiority, Rick Lange commented: “I’m just a simple guy. If something is not noninferior then it’s inferior.” He then asked “how do we recommend an inferior therapy to patients?”

Ultimately, however, the panelists agreed with Page that the “totality of data argues in favor of clinical choice,” although they were unable to define that choice with any precision.

Watchman has been under development for more than a decade and its approval has twice been postponed by the FDA. Most of the controversy over the device has centered around two clinical trials. Although the initial PROTECT AF trial was technically a positive trial, it had a number of important weaknesses and in 2010 the FDA required the company to perform another clinical trial to demonstrate the long-term safety and effectiveness of the drug. The PREVAIL trial was then designed to supplement PROTECT AF. The initial results appeared somewhat promising, but the complicated trial design, with three co-primary endpoints and a novel and difficult-to-understand Bayesian trial design, led to considerable controversy. Based on complete results from the trial, FDA reviewers and panel members agreed that it failed to show that Watchman was an acceptable alternative to warfarin.

October 7th, 2014

Another Reason for Open Access to Clinical Trial Data?

Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, SM

In the Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY) trial the investigators miscounted their endpoints and, last week, published a corrected version in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The discrepancies came to light, in part, because of litigation. The final results do not shift the interpretation of the trial, but should we be bothered that there was a need to correct this in response to litigation? Is this another reason to have data out in the open for others to review?

What is your reaction to this correction?

October 6th, 2014

Selections from Richard Lehman’s Literature Review: October 6th

Richard Lehman, BM, BCh, MRCGP

CardioExchange is pleased to reprint this selection from Dr. Richard Lehman’s weekly journal review blog at BMJ.com. Selected summaries are relevant to our audience, but we encourage members to engage with the entire blog.

JAMA Intern Med October 2014

Medical Device Safety and Effectiveness (OL): I sounded off about the state of medical device control in both Europe and the US a couple of weeks ago. It’s so farcically inadequate you may want to look away. But for the brave, here are some articles brought to you by the editor of JAMA Intern Med, who is an author on one* of them:

Lack of Publicly Available Scientific Evidence on the Safety and Effectiveness of Implanted Medical Devices (free online)

*Assessing the Safety and Effectiveness of Devices After US Food and Drug Administration Approval: FDA Mandated Postapproval Studies

The Food and Drug Administration’s Unique Device Identification System: Better Postmarket Data on the Safety and Effectiveness of Medical Devices

Improving Medical Device Regulation: A Work in Progress (free online)

Lancet 4 October 2014 Vol 384

Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Moving swiftly past the printed Lancet for this week, which is unusually free of interest, we turn to the website and its latest editorial, with the title “Familial hypercholesterolaemia: PCSK9 inhibitors are coming.” Yes, indeed they are, but when should we let them arrive? When they have shown short term safety and good evidence of lowering LDL cholesterol? Or when they have shown long term safety and effectiveness in reducing actual cardiovascular events? Guess what, the two trials on the Lancet website only provide evidence about the first.

PCSK9 Inhibition with Evolocumab (AMG 145) in Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia (RUTHERFORD-2) OL: Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia is the commonest dominantly inherited metabolic disorder in humans, affecting about one person in 250. That’s a market of three million people in the US and Europe. But I don’t think that’s the main reason why at least three drug companies are scrambling to produce monoclonal antibodies to treat it. Beyond these individuals lies the immense market for cholesterol lowering agents to reduce cardiovascular risk in the general population. Evolocumab seems to be ahead from the starting block. It binds to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) which, as you probably know, directs the low density lipoprotein cholesterol receptor to lysosomal degradation, inhibiting its recycling to the hepatocyte surface and thus catabolism of plasma LDL. The evolocumab trials take their names from great physicists who were active 100 years ago. These are given in capitals, as if they were acronyms, but they are nowhere explained in the text. Perhaps just as well. RUTHERFORD-2, a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial, examined the effect of evolocumab in people with heterozygous hypercholesterolaemia, and it yielded a rapid 60% reduction in LDL cholesterol with no more adverse effects than placebo.

Inhibition of PCSK9 with Evolocumab in Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia (TESLA Part B) (OL): It’s tougher work, however, using this strategy in people who carry paired genes which give them very high levels of LDL cholesterol. These rare unfortunates (one in 300 000) have homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia. The TESLA part B trial used a relatively high dose of evolocumab and succeeded in lowering LDL cholesterol by 31% on average at 12 weeks in 33 individuals. But don’t think you have heard the last of this. Soon you will be reading trials of alirocumab and bococizumab, which are also antibodies to PCSK9. One day they could all become Bigbizumab.

The BMJ 4 October 2014 Vol 349

As with the Lancet, so with The BMJ. Let’s go straight to the website. Here are two important papers that refute ideas which I have tended to support. Great. That is what science is all about.

Effects of a Patient Oriented Decision Aid for Prioritizing Treatment Goals in Diabetes (OL): I have argued that our goal in diabetes should be to help people choose which outcomes matter most to them and let their treatment be guided by that. Researchers tried this out in 18 general practices in the north of the Netherlands. The intervention comprised a decision aid for people with diabetes, with individually tailored risk information and treatment options for multiple risk factors. Result: “We found no evidence that the patient oriented treatment decision aid improves patient empowerment by an important amount. The aid was not used to its full extent in a substantial number of participants.” That’s truly disappointing, but it is somewhat similar to Victor Montori’s experience with his own excellent decision aid developed at the Mayo Clinic some years ago. The problem seems to me that we are trying for too much culture change too quickly. That, and the fact that it is pretty impossible to know from the limited evidence we have which drugs for diabetes do what.

Industry Sponsorship Bias in Research Findings (OL): I was immersed in statins for several months this year until I began to drown. With these drugs too, the evidence about adverse effects and benefits is extraordinarily hard to convey in simple terms. Some of my friends take the view that these pills are being foisted on people by big pharma, who have exaggerated their benefits and played down their harms. I don’t believe the first part of that, and I believe that most of the “harms” are small and entirely reversible. But I was open to the suggestion that at least some of the company funded trials might have contained an element of oversell. Now Huseyin Naci and colleagues have done a superb systematic review and network meta-analysis, which reaches the following conclusion: “Our analysis shows that the findings obtained from industry sponsored statin trials seem similar in magnitude as those in non-industry sources. There are actual differences in the effectiveness of individual statins at various doses that explain previously observed discrepancies between industry and non-industry sponsored trials.” Splendid: industry deserves praise where it has acted honourably and provided us with sound knowledge about a genuinely life saving class of drugs.

October 6th, 2014

Nissen Urges Prompt Revision of Cardiovascular Guidelines

Larry Husten, PHD

Sparked by a new study that once again finds serious flaws in the cardiovascular risk calculator at the heart of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cardiovascular guidelines, Steve Nissen states that “the ACC and AHA should promptly revise the guidelines to address the criticisms offered by independent authorities.” The CV risk calculator is a key component of the guidelines, since people are generally considered candidates for statins if they have a 10-year estimated risk of CV disease of 7.5% or higher according to the equations used by the calculator.

In a study published in JAMA Internal Medicine, Nancy Cook and Paul Ridker, analyzing data from the Women’s Health Study, offer fresh evidence that the cardiovascular risk calculator used in the ACC/AHA cholesterol guideline is flawed. They found that the predicted rate of cardiovascular disease using the guideline calculator was significantly higher than the actual observed rate in the trial. They considered and ruled out several “alternative explanations” for the discrepancy, including underascertainment of events and the increased use of statins and revascularization procedures in their population.

Noting that there have been at least seven studies now finding similar flaws in the CV risk calculator, they write that “recalibration of the pooled data sets might provide a solution to this problem.”

In his invited commentary, Nissen writes that “guidelines are effective only when they involve the participation and consent of the stakeholders whose behavior they intend to govern.” Because they were developed without “transparency and public involvement,” he writes, they “represent an important failure of guideline governance and oversight process. Rather than forging a consensus on cholesterol management, the guidelines have further polarized the debate on appropriate use of statin medications.”

Nissen calculates that overestimation of CV risk would lead to millions of additional U.S. patients receiving statins. “While statins are valuable drugs, particularly in secondary prevention, they do have downsides, and prudence requires not administering drugs to patients who will likely not benefit.”

In the future, Nissen proposes, risk calculators should be published and subject to external validation before being adopted. More generally, the guideline process “should be more open and transparent and include a public comment period.”

Elliott Antman, president of the American Heart Association, had the following response to the new publications:

“These comments are the same that we heard and addressed when we published the guidelines last year. Multiple publications since that time have validated the concepts and the utility of the risk assessment tool and cholesterol guidelines. In addition, we continue to receive positive feedback from healthcare providers who use the guidelines as a tool to drive discussions with their patients about appropriate care.”

October 1st, 2014

Case: Testosterone Replacement Therapy and CV Risk

Seth D Bilazarian, MD, Anna Catino, MD and James Fang, MD

A 47-year-old man presents to the hospital reporting 4 days of chest pain that occurs during treadmill exercise, left-arm and jaw discomfort, and shortness of breath with diaphoresis.

His medical history is noteworthy only for orthopedic surgeries and use of testosterone replacement therapy for reportedly low testosterone syndrome. He does not smoke and drinks alcohol only occasionally. He works as a school administrator and a high school sports coach. He has no family history of coronary disease.

The patient is obese, with a weight of 285 pounds and a body-mass index of 37 kg/m2. His physical exam is otherwise unremarkable.

His electrocardiogram is normal. Troponin I levels are 0.03, 0.04, and then 0.05 ng/mL.

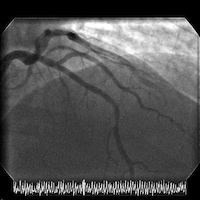

The patient is transferred to a cardiac center for catheterization in the setting of acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Cardiac catheterization reveals normal LV function and an LV end-diastolic pressure of 8 mm Hg. Coronary angiography shows a high-grade mid left anterior descending (LAD) stenosis, which is then successfully treated with a single drug-eluting stent.

Before discharge, the patient has a total-cholesterol level of 184 mg/dL, HDL of 29 mg/dL, LDL of 101 mg/dL, triglycerides of 270 mg/dL, and fasting glucose of 87 mg/dL. The patient is initiated on atorvastatin 80 mg and dual antiplatelet therapy, and he is discharged for follow-up.

Angiograms of the LAD before and after PCI with a drug-eluting stent:

Questions:

1. Did the testosterone replacement therapy play a major role, a minor but significant role (e.g., by amplifying other risk factors), or no role in this patient’s atherothrombotic process?

2. Is it safe to continue the testosterone replacement?

3. According to the ACCF/AHA risk estimator (which is not designed for use in secondary prevention), the patient’s 10-year ASCVD risk before the ACS was 5.1%; therefore statin therapy would not have been recommended. In secondary prevention, should we treat a patient who takes testosterone replacement differently than we treat a patient with multiple atherothrombotic risk factors or a higher risk according to the risk estimator?

4. When the patient’s risk is optimized, he loses weight, and he completes his dual antiplatelet therapy, could testosterone replacement be reinitiated safely (if it is stopped initially)?

5. Does the patient need lifelong statin therapy?

Response:

October 7, 2014

Questions:

1. Did the testosterone replacement therapy play a major role, a minor but significant role (e.g., by amplifying other risk factors), or no role in this patient’s atherothrombotic process?

Although observational data correlate low testosterone levels with CV risk, it remains to be seen whether treating low levels in the absence of symptomatic hypogonadism is beneficial. In fact, randomized trials of treatment for other reasons have suggested a signal of harm, particularly in patients with underlying CAD and the elderly. Therefore, a potential role for harm in this case could be made, despite the patient’s age.

2. Is it safe to continue the testosterone replacement?

We would not continue testosterone therapy without unequivocal evidence of a symptomatic hypogonadal state, particularly in light of evidence of harm in recent randomized trials of testosterone supplementation.

3. According to the ACCF/AHA risk estimator (which is not designed for use in secondary prevention), the patient’s 10-year ASCVD risk before the ACS was 5.1%; therefore statin therapy would not have been recommended. In secondary prevention, should we treat a patient who takes testosterone replacement differently than we treat a patient with multiple atherothrombotic risk factors or a higher risk according to the risk estimator?

In secondary prevention, atherosclerosis is already present, so the priority is treatment of the atherosclerosis itself to reduce the morbidity and mortality of the disease. The use of testosterone replacement should be limited to treating patients with specific hypogonadal symptoms rather than modifying atherosclerosis disease progression. Otherwise, the secondary treatment should be no different than for other patients with known atherosclerosis.

4. When the patient’s risk is optimized, he loses weight, and he completes his dual antiplatelet therapy, could testosterone replacement be reinitiated safely (if it is stopped initially)?

His testosterone levels should be re-assessed (two early morning levels, as recommended by endocrine societies) after significant weight loss. We suspect that this patient’s testosterone levels will change and may even correct if his obesity were to be reversed. Low testosterone may simply reflect other CV risk factors or be driven by atherosclerosis itself (i.e., a risk marker rather than a risk factor). If his testosterone levels remained low, we would treat only in concert with an endocrinologist if a truly symptomatic hypogonadal state could be confirmed.

5. Does the patient need lifelong statin therapy?

Yes, given that he has atherosclerosis, which needs treatment independent of his testosterone status.

Wrap-Up:

October 21, 2014

The patient was discharged the day after his successful PCI. He was seen one week later by his clinical cardiologist, who recommended therapeutic lifestyle changes, continuation of dual antiplatelet therapy, and maintenance of statin therapy (atorvastatin 80 mg, once daily). Cardiac rehabilitation was recommended, but the patient declined. The patient was advised to discontinue the testosterone replacement therapy that he had started before his myocardial infarction.

The table shows the patient’s lipid values during his hospitalization (in March) and 3 months later (in June).

|

March value |

June value |

|

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) |

163 |

90 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) |

101 |

43 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) |

27 |

26 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) |

176 |

103 |

The patient’s weight fell from 285 pounds (BMI 37) to 251 pounds (BMI 34).

Despite the recommendation to discontinue testosterone replacement therapy, the patient resumed it after discussion with his primary care provider, who had originally prescribed it. The PCP recommended that it be continued, given the lack of data on potential hazards and the symptom improvement it had yielded for the patient.

September 30th, 2014

Genetic Analysis Fails to Support Vitamin D to Prevent Diabetes

Larry Husten, PHD

A vitamin D pill can’t substitute for a healthy diet and sunshine, a new genetic study published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology suggests. In recent years many people have been seduced by observational studies that found low levels of vitamin D in people who developed type 2 diabetes. The new study instead suggests that the association is not causal, and that raising vitamin D by itself will not be helpful.

Researchers in the U.K. performed a Mendelian Randomization study in more than 100,000 people in which they examined the effect of four separate, single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on genes that have a known effect on vitamin D levels. Despite the significant effect of these genetic variations on circulating levels of vitamin D (25(OH)D), the researchers found no relationship between genetically determined levels of vitamin D and the risk for developing type 2 diabetes.

Added to previous evidence, write the authors, the results “suggest that interventions to reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes by increasing concentrations of 25(OH)D are not currently justified.” Instead, they write, “our findings emphasize the need for investigation of the discrepancy between the observational evidence and the absence of causal evidence.” Two possible confounders are physical activity and adiposity, they add.

Results of several long-term randomized trials will be needed to definitively prove that vitamin D supplements are not beneficial, say Brian Buijsse in an accompanying editorial. He cautions that “Mendelian randomisation studies need careful interpretation,” but an analysis of previous trials “do not offer much hope that vitamin D supplementation can be used to prevent type 2 diabetes.” He concludes that “the sky is becoming rather clouded for vitamin D in the context of preventing type 2 diabetes.”