January 15th, 2015

Low-Quality Discharge Summaries May Have Consequences

Leora Horwitz, MD

The CardioExchange Editors interview Leora Horwitz about her research group’s study of the association between the quality of discharge summaries and risk for readmission for heart failure. The article is published in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes.

CardioExchange Editors: Please summarize your findings for our readers.

Horwitz: We collected more than 1500 discharge summaries, from 46 hospitals around the nation, as part of a large randomized controlled trial (Telemonitoring to Improve Heart Failure Outcomes). All summaries were for patients who had been hospitalized with heart failure and who survived to discharge. We found that not a single patient’s summary met all three criteria of being prepared in a timely manner, being transmitted to the right physician, and being fully comprehensive in content. We also found that hospitals varied very widely in their average quality. For instance, at some hospitals, 98% of summaries were completed on the day of discharge; at others, none were. In the accompanying data report, we show that summaries that are transmitted to outside clinicians and that include more key content elements are associated with lower risk for rehospitalization within 30 days after discharge. This is the first study to show an association between discharge-summary quality and risk for readmission.

Editors: What are the obstacles to creating timely discharge summaries with good content?

Horwitz: As a practicing clinician, I am acutely aware of the challenges in creating high-quality discharge summaries. With ever-declining lengths of stay, patients are coming and going with extreme speed, leaving little time for clinicians to prepare paperwork. There are always competing time demands. New patients absolutely should have a full workup, history, and physical completed within 24 hours, and existing patients require a note every day. By contrast, few hospitals in my experience require that the discharge summary be completed on the day of discharge. When faced with competing requirements (one patient has a hard deadline and the other doesn’t), it is easy to focus on the one with the deadline.

To date, electronic medical record systems have offered little help. Most of the discharge summaries in our dataset were still being dictated or even being handwritten, thereby requiring clinicians to create all the content on their own. Out-of-the box discharge-summary templates on most electronic health record systems are little but computerized shell forms that leave nearly all the work to the clinician.

For instance, Yale-New Haven Hospital was only recently able to fundamentally redesign its discharge-summary template to automatically pull in laboratory studies that were pending at the time of discharge, as well as the discharge vital signs — crucial to safe transitions of care but typically omitted from summaries. The summary is now also automatically routed to the primary care physician, which eliminates another manual step commonly omitted by busy inpatient physicians.

Editors: How much effect do you think poor discharge summaries have on readmission and clinical outcomes? Do they matter?

Horwitz: Previous studies had not been able to identify an association between discharge-summary quality and risk for readmission or other adverse outcomes. Our accompanying data report, however, shows that elements of discharge-summary quality are indeed associated with readmission risk, suggesting that better-informed outpatient clinicians may be better equipped than less-informed clinicians to care for patients after discharge.

It is possible that the hospitals whose policies encourage prompt completion of discharge summaries and transmission to outside clinicians also have high-quality medication reconciliation processes, routine post-discharge follow-up calls, and so on. That is, discharge-summary quality may be important in its own right and/or it may be a marker of high-quality transitional-care practices. Without a randomized controlled trial (which would be unethical), we cannot know definitively. Nevertheless, our results — combined with the obvious importance of physician communication — lend strong support to efforts to improve discharge-summary quality. Many institutional policies and information-technology changes could make material differences in discharge-summary quality. Busy clinicians need not be asked to solve all of this on their own.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

How timely and complete are discharge summaries at your institution? Will Dr. Horwitz’s study influence the importance you ascribe to discharge summaries?

January 14th, 2015

Hidden Clinical Trial Data: A Dam About to Burst

Larry Husten, PHD

Two important new developments may mean that many more researchers will soon be able to access and analyze data from many more clinical trials.

In recent years, in response to troubling and far-reaching questions about the availability and reliability of clinical trial data, reformers have called for new policies that would require drug companies and other clinical trial sponsors to provide outside researchers access to the data. The two announcements today appear to bring the open data movement closer to the tipping point.

In the first development, a preliminary report from the prestigious Institute of Medicine lends strong support to the open data movement. The IOM report states that investigators should be required to establish a data-sharing plan at the same time the trial is registered. The report includes detailed recommendations for when and how the data should be made available. Among the major recommendations: data underlying a trial analysis should be made available within 6 months after journal publication, and all data should be made available no later than 18 months after the last patient visit in the trial.

In the second development, the Yale University Open Data Access (YODA) Project announced that Johnson & Johnson is expanding its plans to share data. The company had previously announced that it planned to share data from its large drug portfolio. Now the company has announced that it will also share data from its device and diagnostic trials — a first in the field. YODA will act as “a fully independent intermediary to manage requests and promote data use,” said YODA. The project will have “full control” over the data.

The “guiding principle” of the IOM report “is that participants put themselves at risk to participate in clinical trials,” writes panel member Jeffrey Drazen, in a perspective published in the New England Journal of Medicine. “The clinical trial community therefore has the responsibility to reward that altruistic behavior by widely sharing the information gathered so that as much useful knowledge as possible can be wrought from the data.”

Says Drazen: “We need to change how we think about data. We need to view it as a community resource, much like a shared park, rather than as personal property.”

Harlan Krumholz, head of the YODA project (and editor-in-chief of CardioExchange), commented on both developments: “It is gratifying to see the IOM come out strongly for data sharing. At this point they are codifying what is an emerging consensus and unstoppable growing momentum for open science in medical research. How we ever developed a culture that favored researchers over society is a good question – but the good news now is that we are firmly on our a way to a better, more responsible scientific culture. It is no longer just the voices of those outside the power structures that are calling for change.”

A statement from the IOM notes that “no body or authority currently is capable of enforcing the recommendations offered in the report.” The committee suggests that the study sponsors — which include the NIH, the FDA, large foundations, and major pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies — “take the lead to convene a multi-stakeholder body with global reach and broad representation to address, in an ongoing process, the key challenges associated with sharing clinical trial data.” The IOM panel was chaired by Bernard Lo, president of the Greenwall Foundation.

January 14th, 2015

Ticagrelor Improves Outcomes After Myocardial Infarction

Larry Husten, PHD

For the first time, a very large trial has shown that dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) improves cardiovascular outcomes when given to patients 1 to 3 years after a myocardial infarction. Because DAPT has been shown previously to reduce the high risk of recurrent events for up to a year following an MI, it is considered to be standard therapy during this time period. But whether or not longer-term treatment after a year would be also beneficial has been controversial.

AstraZeneca today announced that the Pegasus-TIMI 54 study had successfully reached its primary endpoint. More than 21,000 patients were randomized to receive either ticagrelor (Brilinta, 60 or 90 mg twice daily) or placebo in addition to aspirin. Therapy was initiated 1 to 3 years after MI in patients who also had one additional risk factor. The primary endpoint was the composite of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke. The company said that no safety issues had been found and that the full results of the trial would be presented later this year.

Pegasus-TIMI 54 is the second in a series of trials sponsored by AstraZeneca exploring a broad range of indications for ticagrelor. PLATO, the first trial, earned FDA approval of the drug for an ACS indication, but the drug has labored under intense criticism of the trial. In recent months, some of this criticism has started to resolve. Additional trials are now underway testing ticagrelor’s role in patients with peripheral arterial disease, with ischemic stroke or TIA, and with diabetes and coronary atherosclerosis.

January 13th, 2015

40-Year Effort in One Rural County to Prevent Cardiovascular Disease Found Successful

Larry Husten, PHD

A 40-year program in one poor rural county to combat cardiovascular disease appears to have been successful, resulting in reduced rates of hospitalization and death compared with other counties in the same state over the same period. The new findings are described in a paper published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Beginning in 1970, Franklin County, Maine began a nearly unprecedented, comprehensive, county-wide program to improve cardiovascular risk. The program sought to help residents lower elevated blood pressure and cholesterol levels, quit smoking, improve their diets, and increase their physical activity. During the program, county residents, who numbered 22,000 at the start of the study, had more than 150,000 individual interactions with the program. The program was created and run by local public officials, physicians, and the community hospital.

When compared with other counties in Maine, Franklin County had a higher-than expected, income-adjusted total mortality rate before the start of the program. After the start of the program, mortality was significantly lower than expected. There was a similar reduction in hospitalization rates, resulting in a cut of $5.4million in county hospital charges each year.

Other risk factors also improved at different points over the study period as new initiatives were implemented. Blood pressure control increased from 18.3% in 1975 to 43.0% in 1978 . Control of elevated cholesterol increased from 0.4% in 1986 to 28.9% in 2010.

Because this is not a report from a randomized trial, it is impossible to state with full confidence that the findings are a genuine result of the program. But in an accompanying editorial, Darwin Labarthe and Jeremiah Stamler write that the findings appear plausible given that the individual interventions used have been found to be effective previously. The report, they say, should “reinforce the importance of cardiovascular health promotion and disease prevention policies and practices at the community level; stimulate efforts in communities to document and publish their past experience in this area to inform related ongoing work; and foster wider application of program evaluation and implementation research, exploiting new data sources and technologies to accelerate replication and scaling up of community-based prevention.”

January 12th, 2015

Selections from Richard Lehman’s Literature Review: January 12th

Richard Lehman, BM, BCh, MRCGP

CardioExchange is pleased to reprint this selection from Dr. Richard Lehman’s weekly journal review blog at BMJ.com. Selected summaries are relevant to our audience, but we encourage members to engage with the entire blog.

Ann Intern Med 6 Jan 2015 Vol 162

D-dimer Testing to Select Patients With a First Unprovoked Venous Thromboembolism Who Can Stop Anticoagulant Therapy (pg. 27): Having an unprovoked deep vein thrombosis is a powerful risk factor for having a second DVT. The risk declines over time but never quite goes away. Researchers in Canada sought to establish whether it would be useful to measure D-dimer before stopping anticoagulation, and then, if the D-dimer was negative, stop the anticoagulants, measure it again after a month and restart the drugs if it had become positive. Or leave them off if both tests were negative. It didn’t quite work in men, who showed a 9.7% annual recurrence rate even after two negative tests. In women the rate was 5.4%, which might just be acceptable.

Effects of Blood Pressure Reduction in Mild Hypertension (OL): Are you the kind of clinician who actually treats blood pressure? If you’re a GP, that means you’re probably responsible for about 400 people taking drugs for let’s say an average of 15 years = 52 million drug-hours. So do click on the link and take half an hour of your own time to mull over this free systematic review of the effects of BP reduction in mild hypertension. Consider what you are trying to do. Reduce cardiovascular risk, right? If you have come across John Yudkin’s Ten Commandments, you will remember the one that says “Thou shalt treat according to level of risk and not to level of risk factor.” So for each “patient” on BP-lowering medication, you have calculated a risk score such as QRISK? And discussed each element of it with each individual and what non-drug and drug treatments might help to reduce it? Giving every person an individualized number-needed-to-treat and number needed-to-harm for each intervention? If you have answered yes to all of these questions, you must be lying, because the information to support this detail of shared decision making simply isn’t there. This review, which lumps together all sorts of individuals—with and without diabetes, some with previous treatment and some not—ends up concluding that treating people with “grade 1 hypertension” is probably going to reduce cardiovascular events but that the confidence intervals are huge. So which risk-reducing intervention is it going to be? More physical activity? A statin? A BP lowering agent? A more “Mediterranean” diet? Metformin? All of the above, or none of them? After all, it is the symptomless individual who has to decide on the basis of the information you give them. This is the mess we are in and the mess we need to get out of if shared decision making about risk reduction is going to become a reality. Because “mild hypertension” is not a thing in itself: it is just a single risk factor. And “all-cause mortality”—the thing that gets us all in the end—does not seem to be postponed by any of the mild BP treatments described in this paper.

JAMA Intern Med Jan 2015

Association Between Dietary Whole Grain Intake and Risk of Mortality: Perhaps the grim reaper can be held off a while by eating more whole grain products. This is one possible conclusion to be drawn from dietary information fed into those two familiar American cohort studies, 74 341 women from the Nurses’ Health Study (1984–2010) and 43 744 men from the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (1986–2010). ” These data indicate that higher whole grain consumption is associated with lower total and CVD mortality in US men and women, independent of other dietary and lifestyle factors.” So the genes that make people like to eat grainy things may be associated with the genes that make people die less from cardiovascular disease. Or maybe the grainy things themselves have that effect. Either way, I shall eat what I like, avoiding buckwheat and couscous and similar vile things.

Lancet 10 Jan 2015 Vol 385

Efficacy and Safety of LDL-Lowering Therapy Among Men and Women (OL): The Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration offer a paper on “Efficacy and safety of LDL-lowering therapy among men and women: meta-analysis of individual data from 174 000 participants in 27 randomised trials.” But although there is now some weak evidence LDL-C lowering with ezetimibe may improve cardiovascular outcomes, all the evidence in this review is about statins. These drugs certainly lower LDL-C and “These results indicate that, for each 1 mmol/L reduction in LDL cholesterol, statin therapy reduced major vascular events by about a fifth, major coronary events by a quarter, coronary revascularisations by a quarter, and ischaemic stroke by just under a fifth, and that these proportional reductions were similar in men and women, even though on average women had somewhat lower absolute cardiovascular risk in these trials.” But it’s not just pedantic obstinacy that makes me chary about putting all this down to LDL-C lowering. I’m worried that people will therefore carry on treating cholesterol as some kind of target independent from total cardiovascular risk, whereas we need always to obey the commandment “Treat to level of risk and not to level of risk factor.” And scientifically I still can’t understand how statins can produce marked improvements in acute events before they have had time to reduce HDL-C.

January 12th, 2015

High Rate of Inappropriate Use of Aspirin for Primary Prevention

Larry Husten, PHD

More than a third of U.S. adults — more than 50 million people — now take aspirin for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Although it was once broadly recommended, aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease is now only indicated in people who have a moderate-to-high 10-year risk. Now a new report published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology finds that there are still a significant number of people who are receiving aspirin inappropriately.

Different medical groups have various recommendations about the precise indications for aspirin for primary prevention, but there is broad agreement that aspirin is not appropriate in people who are at low risk, defined as a 10-year risk below 6%. Using data from more than 68,000 primary-prevention patients receiving aspirin who were followed in the National Cardiovascular Disease Registry Practice Innovation and Clinical Excellence (PINNACLE) Registry, researchers calculated that 11.6% of the patients had a 10-year risk below 6%. Women were more likely than men to receive aspirin inappropriately. Inappropriate use varied significantly at the practice level, ranging from 7.2% in the lowest quartile to 13.6% in the upper quartile. People who received aspirin inappropriately were 16 years younger, on average, than people who received aspirin appropriately. Over time the rate of inappropriate use has declined, from 14.5% in 2008 to 9.1% in 2013.

“Our findings suggest that there are important opportunities to improve evidence-based use of aspirin for primary CVD prevention.” the authors concluded.

In an accompanying editorial, Freek Verheugt expresses concern that “the benefit of aspirin may be overshadowed by the bleeding hazard,” especially since the bleeding risk appears to be strongly correlated to the ischemic risk of the patient. He further speculates that because for many patients statins and other drugs will have already produced a substantial reduction in risk, any benefit from aspirin will have been almost completely eliminated.

January 9th, 2015

Top 10 CardioExchange Posts from 2014

Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, SM and John Ryan, MD

“Happy 2015! We thought you might like to see last year’s top viewed CardioExchange stories. The posts on PARADIGM led the way. An interesting post that asked about whether doctors are miserable was remarkably popular, begging the question whether we are all worried about how we and our colleagues are experiencing medicine. Prevention and decision-making also dominated the top viewed posts — whether about statins, atrial fibrillation, new guidelines, or tools. We hope you enjoy seeing these again, and we look forward to working with you in 2015.” – Harlan Krumholz

“2014 was an exciting time in cardiology, as there was no shortage of news or new ideas. The lipid debate continued with considerable disagreement around risk predictors and target levels. For the first time in a while, it seemed that a new heart failure therapy might soon be available in the form of LCZ-696. And there is still discussion and uncertainty about how best to manage A-fib. We want to thank all our readers for their support and insight over the past year, and in recognition of your support we present the most read articles from 2014.” – John Ryan

Top 10 Stories

- Perspectives on PARADIGM-HF

- My Fellow Doctors, Are You Miserable?

- Will There Be a PARADIGM Shift in Treatment of Heart Failure?

- HPS2-THRIVE: The Final Chapter in the Niacin Story?

- A New Tool to Discuss Primary Prevention with a Statin with Patients: Life Expectancy Gain

- What Is “Non-Valvular” Atrial Fibrillation?

- SERIES: Making Sense of the New Prevention Guidelines — The View from Clinical Practice

- The Risk-Prediction Conundrum: Individual Risk vs. Population Risk

- Perioperative Beta-Blockade: Between a Rock and a Hard Place

- A New Approach for the Statin-Intolerant Patient?

January 9th, 2015

FDA Approves New Oral Anticoagulant from Daiichi Sankyo

Larry Husten, PHD

And then there were four.

Late Thursday the FDA announced that it had approved edoxaban, the new oral anticoagulant manufactured by Daiichi Sankyo. The drug will be marketed under the brand name of Savaysa and joins three other new drugs in the large and important new oral anticoagulant marketplace: dabigatran (Pradaxa), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), and apixaban (Eliquis). All four drugs were designed to overcome the limitations of warfarin, which has long been available as an inexpensive generic drug but which requires extensive monitoring and dose adjustment and has numerous interactions with other drugs and foods.

The FDA approved two indications for edoxaban: for reducing the risk of stroke in patients who have non-valvular atrial fibrillation (AF) and for treating deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in patients who have already been receiving an anticoagulant by injection or by infusion for 5 to 10 days.

Last October the FDA’s Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee voted 9-1 in favor of approval for the AF indication. But the positive vote did not fully reflect the panel’s concerns about the drug, which centered on a troubling subgroup analysis in the otherwise positive Engage AF-TIMI 48 trial. This analysis suggested that the benefit associated with edoxaban occurred exclusively in the large group of patients with impaired renal function (and, therefore, presumably, higher circulating levels of the drug). There was a trend suggesting that edoxaban was harmful in the subgroup of patients with normal renal function. Although subgroup analysis is often tricky, both the FDA reviewers and panel members felt that this was a biologically plausible phenomenon that could have important clinical implications.

As a result of this finding, edoxaban will contain a boxed warning that the drug is less effective in AF patients with a creatinine clearance greater than 95 ml/min. Physicians should measure creatinine clearance before initiating treatment with edoxaban. People with creatinine clearance levels over 95 ml/min should receive a different anticoagulant.

Bleeding is the most serious side effect of edoxaban, as with all anticoagulants. Currently there is no treatment that has been shown to reverse the anticoagulant effect of the drug. Premature discontinuation of edoxaban increases the risk of stroke.

January 5th, 2015

Screening Heart-Failure Patients for Cognitive Impairment at Discharge

Eiran Gorodeski, MD, MPH

The CardioExchange Editors interview Eiran Gorodeski about his research group’s study of cognitive-impairment screening for patients who are hospitalized for heart failure. The study is published in Circulation: Heart Failure.

CardioExchange Editors: Please summarize your main findings for our readers.

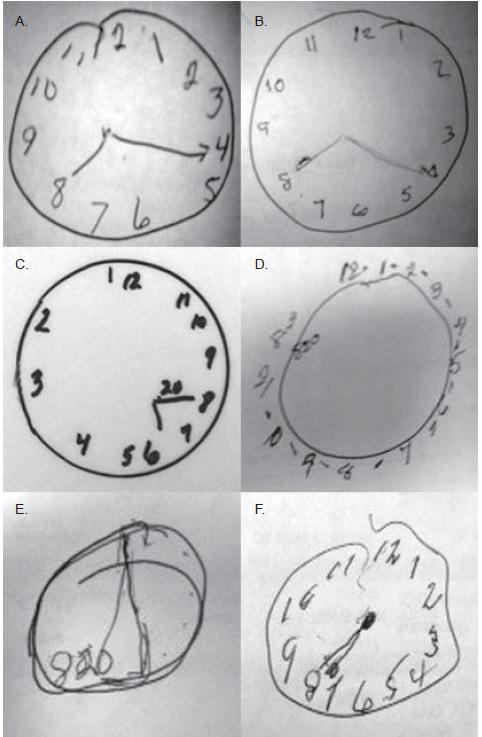

Gorodeski: We used a brief cognitive-impairment test — the Mini-Cog (three-word recall and clock-draw test) — to screen 720 consecutive older adults who were hospitalized for heart failure (HF) at Cleveland Clinic. Nearly a quarter of this population performed poorly on the Mini-Cog, thereby meeting criteria for cognitive impairment. Poor performance on the Mini-Cog was associated with significantly elevated adjusted risks for all-cause rehospitalization and all-cause mortality.

CardioExchange Editors: When and how did you start to think about this study?

Gorodeski: Several years ago, a group of us (a cardiologist, a geriatrician, and home-care specialists) decided to collaborate on a care-transitions and telehealth program intended to reduce rehospitalizations for HF. As the cardiology lead, I assumed that many of the patients would be readmitted for HF decompensation and, as such, designed the program to focus on decompensation monitoring and intervention. We regularly reviewed our efforts and program outcomes and discovered that most of the readmissions were unrelated to HF.

At first I found this very irritating. How could we reduce readmissions if HF exacerbations were not the cause? Our home-care nurses shared many anecdotes about homebound older adults who had insufficient support and were struggling to understand their medical condition and complex treatment regimens. They described patients who were completely unable to execute even seemingly simple tasks, such as organizing their medications. Our geriatrician co-lead suggested that cognitive impairment could be a common denominator, and we decided to implement routine Mini-Cog assessment for all patients entering our program.

When we saw the grotesque-looking Mini-Cog clocks that some of our patients were drawing in the hospital, often showing the wrong time or with other grossly incorrect features, we realized that an image is worth a thousand words.

Here are clocks drawn by several patients that are featured in a recent Circulation tweet:

We asked our nurses to photograph the clocks with their iPhones and upload the images into the EMR so that other team members could view the misdrawn clocks, not just the Mini-Cog score. We did this for several years as part of routine clinical care, and then we went back to assess the cognition data more formally. That is how the study began.

CardioExchange Editors: What does this study mean for physicians? Should doctors be assessing cognitive function for all patients at discharge?

Gorodeski: I think that doctors should view cognitive function as a “vital sign,” like blood pressure and pulse rate. This ultra-short screening test, which takes fewer than 3 minutes to perform, can be completed by any clinical personnel. Knowing what I know now, I would say that cognitive function in patients with heart failure is probably a more important predictor of short- and intermediate-term outcomes than any of the traditional vital signs.

I also now realize that cognitive impairment is subtle and could be missed frequently if not formally assessed. Physicians’ ultra-brief interactions with HF inpatients on daily hospital rounds are probably insufficient to help us understand their cognitive function. I have seen many patients who smile and greet me in a seemingly normal fashion, but when I challenge them with the Mini-Cog, they exhibit poor recall and fail to draw a clock appropriately. I hope that our study will draw attention to the high prevalence of cognitive impairment in patients hospitalized for HF — and to the fact that its presence could be a sign of impending danger and should not be ignored.

Finally, the Mini-Cog may be a more powerful readmission risk-prediction tool than any existing risk models we have, which is really mind-boggling. This has to be studied further.

CardioExchange Editors: How should management be changed for patients with mild to moderate cognitive function?

Gorodeski: I suspect that we can use the Mini-Cog assessment to guide resource utilization. To achieve better outcomes, patients with cognitive impairment are likely to need a structured care environment and engaged caregivers. In our study, cognitively impaired patients who were transferred to skilled nursing facilities had better outcomes in the short run, compared with cognitively impaired patients who were discharged home. That is probably because of the facilities’ highly structured environments.

Interestingly, in our study, “plain vanilla” home care did not seem to make a difference for cognitively impaired patients who were discharged home. I suspect that those patients need more-intensive daily supervision and assistance than what routine home care currently provides. I am hopeful that such intensive, home-based interventions can be designed, because ultimately patients desire most to be at home, and that is where they do best. In contrast, HF patients who are cognitively intact may not need intensive hands-on interventions; “light touch” telehealth monitoring for early disease decompensation may be more appropriate and helpful.

CardioExchange Editors: Do you have any plans for a next study in this area?

Gorodeski: My immediate plans are to raise awareness about cognitive impairment and about its value as a “vital sign” for patients served by the cardiology and broader healthcare community. I have started doing this by tweeting images of clocks drawn by cognitively impaired HF patients who were in our study. I also plan to work toward routinely screening the cognitive ability of patients hospitalized for HF at my home institution.

Many questions related to cognitive impairment in heart failure need to be studied further. I am most interested in whether and how cognitive impairment fluctuates during acute and post-acute hospitalization for heart failure, how to utilize cognition as a vital sign along with other markers of risk for readmission, and whether any novel models of post-acute care can specifically help this population of patients. This timely and exciting area of investigation may be best addressed in a multidisciplinary fashion.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

How does Dr. Gorodeski’s research affect your interest in screening hospitalized heart-failure patients for cognitive impairment? View more examples of the clocks at http://www.eirangorodeski.net.