May 1st, 2013

Which Wedge to Believe?

Tariq Ahmad, MD, MPH and James Fang, MD

A 39-year-old African American man with hypertension and diabetes reports a cough, shortness of breath, and increasing lower-extremity edema of 3 weeks’ duration. He denies chest pain, palpitations, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea.

His vital signs are normal except for oxygen saturation of 90% on room air. Physical examination reveals jugular venous distension to the angle of the jaw, a widely split S2, a right ventricular (RV) heave, a right-sided S3, clear lungs, a distended abdomen, and bilateral lower-extremity edema. An electrocardiogram documents sinus tachycardia, nonspecific T-wave changes, and right-axis deviation.

Given the clinical presentation and suspicion for pulmonary hypertension, the patient is hospitalized. A transthoracic echocardiogram reveals normal left-ventricular function, an enlarged right atrium and right ventricle, moderate tricuspid regurgitation, and an estimated RV systolic pressure of 88 mm Hg.

Right-heart catheterization is ordered. It identifies severe pulmonary hypertension (mean pulmonary artery pressure, 95 mm Hg) and markedly variable pulmonary capillary wedge pressures among lung segments, ranging from 12 mm Hg in the right middle lobe to 45 mm Hg in the left lower lobe.

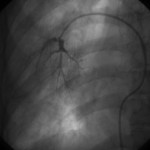

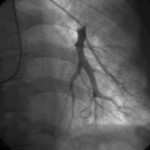

Wedge angiograms reveal a significant delay in venous emptying patterns on one side (see images).

Questions:

1. How do you interpret the large differences in wedge pressures?

2. How do you interpret the wedge angiograms?

3. What additional testing would you perform?

4. What is your differential diagnosis?

Response:

May 8, 2013

1. The most common cause of differential wedge pressures is partial wedging of the catheter. This is a reasonable possibility when there is no suspicion of left-heart disease or when the nature of the waveform suggests it (e.g., something between a true wedge pressure and pulmonary-artery pressure). A proper wedge pressure can be confirmed using wedge oximetry (pressure >95%, or equal to arterial saturation); obtaining left-atrial pressure; measuring simultaneous LV end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP); or, as in this case, performing a wedge angiogram.

If the wedge pressures are accurate, there appears to be variable downstream obstruction to venous drainage. Given that echocardiography shows no obstruction to LV inflow, the obstruction seems to lie in the pulmonary venous system.

2. The wedge angiograms confirm the wedge position in both lungs and also reveal differences in the pulmonary arterial system.

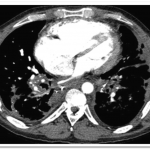

3. At the time of catheterization, I would obtain a simultaneous LVEDP to confirm the difference between that measurement and the pulmonary capillary wedge pressure. Cardiac and chest CT are appropriate for examining the pulmonary venous anatomy, and high-resolution chest CT should be used to assess the lung parenchyma. Pulmonary-function tests usually show a decline in diffusion capacity. Some clinicians would consider a ventilation-perfusion scan, but it may not be able to distinguish pulmonary arterial hypertension from pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Lung biopsy is a high-risk diagnostic procedure in this clinical setting.

4. Veno-occlusive disease is the primary diagnostic consideration, as it can be associated with parenchymal pulmonary diseases, malignancies/chemotherapy (especially after bone-marrow transplant), hypercoagulable states, and (possibly) toxins or infections. If the patient has undergone catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation or lung transplantation, pulmonary venous stenosis should be considered.

Follow-Up:

May 17, 2013

The pulmonary angiograms raised a concern for pulmonary venoocculsive disease, prompting a cardiac MRI that showed evidence of pulmonary vein occlusion (especially L-sided). CT of the chest revealed diffuse peri-bronchovascular bundle thickening with peripheral nodular opacities, as well as multiple hilar and mediastinal calcified lymph nodes—findings most consistent with sarcoidosis (see images below). Biopsy of a mediastinal lymph node showed non-necrotizing granulomatous lymphadenitis, consistent with a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.

Final diagnosis: Severe pulmonary hypertension and right-heart failure, caused by extrinsic compression of the pulmonary venous structures due to sarcoidosis-related lymphadenopathy

I would suggest CT scan or MRI to look at the pulmonary veins.

Might it be pulmonary veno-occlusive disease

Agree, I was thinking veno-occlusive disease as well.

Chronic thromboembolic disease vs pulmonary veno-occlusive

Perform CT scan or MRI and V/Q lung scan.

Consider unilateral pulmonary AV fistula

chronic pulmonary embolism, a trial with anticoagulants should be given.

Mostly veno occlusive disease

i think repeated shower of pulmonary embolism, better to add venous duplex of lower limb, and Ct ,lung ventilation per fusion scan