August 18th, 2014

Disparities in Healthcare: Young Women Continue to Fare Worse than Men after an AMI

Aakriti Gupta, MD

CardioExchange recently had the pleasure of discussing with Dr. Aakriti Gupta the findings of her study “Trends in Acute Myocardial Infarction in Young Patients and Differences by Sex and Race,” published recently in JACC. Here is her analysis of the problems as well as her proposed solutions.

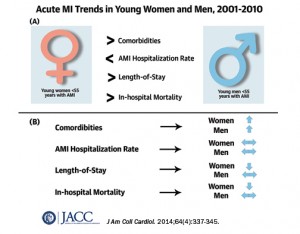

Even though more than 30,000 women less than 55 years of age suffer from acute myocardial infarction (AMI) every year in the US alone, young women remain a vulnerable, yet understudied group with worsening cardiac risk profiles and worse outcomes as compared with men. Our study, published recently in JACC, shows that these healthcare disparities in cardiovascular disease are persistent, although have a favorable trend. Three points about AMI in the young to take away from this study are as follows:

Unlike their Medicare-aged counterparts who showed a 20% decline in hospitalization rates for AMI in a previous study, both women and men with AMI younger than 55 years old showed no significant change.

Unlike their Medicare-aged counterparts who showed a 20% decline in hospitalization rates for AMI in a previous study, both women and men with AMI younger than 55 years old showed no significant change.- Young women with AMI, and black women in particular, have higher disease burden including hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes. Both young women and men showed worsening trends for these co-morbidities through the decade.

- Although impressive declines in in-hospital mortality were noted for women and not for men, significant excess mortality remained for women through each of the 10 years included in our study.

Next Steps:

- Better Data Collection:

To better understand healthcare disparities, collection of high-quality data is key. An American Heart Association national survey showed that only 18 percent of hospitals in 2011 were collecting race, ethnicity, and language data at the first patient encounter. Good quality clinical data is imperative to quantify the contribution of social, economic, biological and genetic factors responsible for healthcare gaps based on gender and race. Such efforts would help guide redirection of our resources appropriately.

- Spread of awareness among public, patients, physicians and policymakers alike:

Several campaigns including the Go Red for Women and The Heart Truth were launched in the previous decade to increase awareness of cardiovascular disease prevention among women. A subsequent survey showed that only half of the young women included in the survey were aware of cardiovascular disease as the leading cause of death in 2009. This issue is even more relevant at the global level, as I imagine the situation may be worse.

- Role of Health Policy:

With expansion of insurance coverage per the Affordable Care Act, there may be several opportunities to focus on health care disparities. In particular, expanded payments for primary care can really benefit Medicaid beneficiaries, many of whom are minorities. In the face of worsening trends of co-morbidities including diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidemia in the young, there is tremendous scope for improved primary prevention in this segment of the population.

- Better Risk Stratification Tools and Implementation in Primary Care:

It is concerning that prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors like hypertension, dyslipidemia, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes was much higher in women through the decade. As pointed out by Drs. Shaw and Butler in the accompanying editorial, risk-based detection tools should form the core of targeted preventive strategies in cardiovascular prevention. Further efforts in this direction could be very high-yield for cardiovascular prevention.

Finally, I would emphasize that there have been substantial mortality declines noted among young women (30% decline from 2001 to 2010). This achievement may be attributed to several positive developments in the past decade including improved awareness, better access to care, better preventive strategies, and more coronary revascularization procedures. Having said that, women continue to have significant excess mortality after AMI as compared with men. Our first step toward reducing health disparities and achieving health equity should be to spread the message.