May 20th, 2011

Data from Our International Survey of Medical School Grads

John Ryan, MD

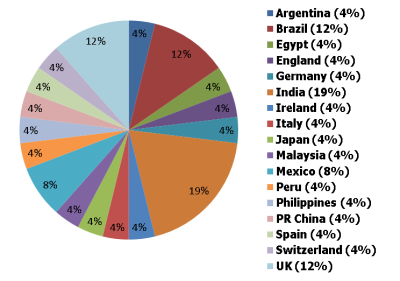

Earlier this year we at CardioExchange surveyed international medical school graduates from our online community. We sent out a questionnaire to 850 internationally based physicians from around the globe and received 29 responses (a 3.4% survey-response rate) from 6 continents. The largest group of respondents (19%) was from India, then 12% each from Brazil and the U.K., with the rest from countries as far ranging as Japan, Egypt, Peru, China, and Switzerland.

Where Our Survey Respondents Graduated from Medical School

Interestingly, although respondents received most of their cardiology training in their native countries, 59% went to the United States to complete it. However, nearly all of those who came to the U.S. said that they intend to return to their home countries eventually. That contradicts previous literature published by the University of Michigan (1995) showing that once international physicians come to the U.S. they tend to stay. However, both the age of those data and the size of our small, informal sample may be among the factors that account for the discrepancy between the two.

In our survey, a plurality of respondents (45%) said they had completed 2 to 4 years of postgraduate training before starting cardiology training. With regard to general cardiology training itself, most respondents (62%) indicated that their native countries require 2 to 4 years, but a substantial percentage (27.5%) said that 4 to 6 years of general cardiology training are required (considerably longer than in the U.S.). Perhaps a partial explanation is that in some U.K. models of Specialist Registrar training, general-medicine training years are built in to cardiology specialty training, thereby increasing the total time logged under cardiology.

About two thirds of our respondents indicated that their general cardiology programs provided training in diagnostic catheterization and echocardiogram interpretation, but a still-remarkable nearly one third said that their programs did not provide training in these modalities. Perhaps the desire to get such training explains why many trainees come to the U.S., but our data do not clarify that point.

Only about half of our respondents said that their native countries required board certification to practice as a cardiologist. As in the U.S., most of these board exams are taken 2 to 4 years after starting cardiology training, although they are a combination of written and clinical examinations (not computerized tests, as in the U.S.).

Work life after completing general cardiology training does not differ much between the U.S. and other countries, according to our respondents. They are, for example, permitted to perform admissions, do consultations, and read ECGs. Consistent with the finding that two thirds received training in diagnostic catheterization, 64% said they went on to do catheterizations in their practices. Interestingly, 84% of respondents describe echocardiogram interpretation as part of their practices, despite the fact that nearly 30% of all respondents said they had not received such training in their general cardiology programs. This disjuncture may be attributable, again, to having received training in the U.S. or, perhaps, to systems in their home countries that allow cardiologists to interpret echos without formal training.

Subspecialty training was available in all the countries represented by our respondents, and 72% planned to undertake it. The most popular subspecialty was interventional cardiology (38% of respondents), with most of the rest roughly evenly distributed among imaging, electrophysiology, research, and heart failure. Although three quarters of respondents interested in subspecialty training intend to do most of it in their home countries, close to half of all our respondents said that they intend to come to the U.S. at some point before their overall training is complete and then to return home.

A quarter of medical school graduates in the U.S. have education-related debt that exceeds $200,000, according to the Association of Medical Colleges (October 2007). In our international survey, about 80% of respondents had less than $6000 in debt accrued over the course of their training, and 43% reported having no educational debt at all.

Modest though our sample was, we’re wondering what your thoughts are about the data our international survey respondents shared with us. What insights do the numbers provide? Any surprises?

Dear John,

There is substantial bias in this survey, especially with a 3% response rate. I really do not believe it is possible to make any reliable statements.

excellent findings…perhaps some reflections of the reverse brain drain from the nineties…mirroring the downtrending economy and excessively rigid regulations in the US……….

Competing interests pertaining specifically to this post, comment, or both:

None

Thanks gentlemen for your comments. You make some great points. As mentioned, this survey was designed as a cross-sectional informal sampling of our international members to view current trends. The strong intention for trainees to return home was definitely a surprise.

This BBC article references Saurav’s thoughts re the reverse brain drain- http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-south-asia-13595196

nice article Dr Ryan-however the reverse brain drain as mentioned till now, has mostly been restricted to the IT/Services/Business sector till now…however healthcare hadnt seen a big efflux of qualified foreign born practitioners-mainly probably for 2 reasons-

1.Monetary incentives were far superior in the 60s and 70s compared to most of even the western world…

2.The opportunities of practicing advanced skills were limited once someone made the trip back and hence qualified practitioners felt disgruntled with the opportunities….

However recently, I believe the monetary aspects definitely have been equilibrated to a large extent with the lure of a significantly better lifestyle in many countries(re 36hr work weeks in many parts of Europe) and with economic strides-the day to day therapies available have become pretty standardised in many areas of the globe….One thing definitely still missing in centers of higher education outside of the US and maybe a select few centers of Europe are probably the initiatives in research and encouragement for scholastic actitvities….so with increasing budget cuts to the NIH and other research institutions-even that issue may get a leveling sometime in the future….

Competing interests pertaining specifically to this post, comment, or both:

None.

Dr. Chatterjee,

I agree with you that there has been a paucity in initiatives in research and scholastic activities in other parts of the world. I think this is improving though. For instance the I recently United Health and NHLBI have started Centers of Excellence (http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/globalhealth/centers/index.htm). These 11 centers were developed over the last few years with the goal to build research and training infrastructures and to conduct research to improve the prevention and management of chronic cardiovascular and lung diseases in these developing countries. Hopefully with initiatives such as this research in the developing world will increase.

thanks Dr Jahangir-very promising article indeed….

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/29/opinion/29bach.html?_r=1

Is this the beginning of a concerted effort to destroy the subspecialties???

Competing interests pertaining specifically to this post, comment, or both:

Cardiology enthusiast.

Thanks Saurav. A good read and very relevant.

Also the fact is that most training hospitals each year get more than 2X the annual salary of a resident or fellow from insurance companies only-that is beside the profit they make through the patient care/clinical services provided by the residents and fellows…so the option of having to pay during training as a subspecialist is nothing short of ludicrous….it might be time to look into the hard economics.Also a factor that the authors of the referenced article seem to be missing is that a medical student in many cases is a twenty something with mostly less debts in terms of housing loans/cars etc-on the other hand-a subspecialist trainee is a mid 30s something with often a family depending on him………

Competing interests pertaining specifically to this post, comment, or both:

Cardiology enthusiast.

I think we must pay the doctors sufficient in training .The entire payment system needs to be re-looked if we want the medical profession to remain attractive, otherwise it already is less sought after profession.we must understand that a 25 yr old doctor has the same capability as an MBA drawing a good salary.