September 9th, 2010

Protective Effect of Education Only Occurs in High-Income Countries

Larry Husten, PHD

The well-known cardiovascular protective effect of education only occurs in high-income countries (HICs), according to a new report from the REACH registry appearing in Circulation. A striking finding was that highly educated women were more likely than their less educated counterparts to smoke in both affluent countries and less affluent countries. The authors point out that “studies linking socioeconomic status to cardiovascular outcomes in HICs cannot be extrapolated to LMICs (low- or middle-income countries), particularly for women.” Overall, educational attainment was protective in HICs, but not in LMICs, against obesity, smoking, and hypertension.

September 8th, 2010

New Therapy for a Rare Syndrome

Larry Husten, PHD

A team of French and Belgian investigators have found a promising new treatment for a rare inherited disorder that often leads to vascular dissection or rupture. In a report published online in the Lancet, Kim-Thanh Ong and colleagues compared the effect of celiprolol, a beta-blocker with beta-2 agonist properties, with placebo in 53 patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. After 47 months of follow-up, the trial was stopped early when the investigators observed a significant reduction in ruptures or dissections in the celiprolol group compared with the placebo group (5 vs. 14).

In an accompanying editorial, Benjamin Brooke writes that the study “represents a substantial breakthrough in the evidence-based management of the syndrome. Celiprolol is an inexpensive well-tolerated drug available to treat patients with vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome worldwide.”

September 8th, 2010

“Cath Lab, We Have A Problem”?

Richard A. Lange, MD, MBA

According to a recently published study, a huge disconnect apparently exists between patients’ and cardiologists’ beliefs about the benefits of PCI. The patients had been referred for coronary angiography and possible PCI, had discussed PCI with a physician, and had provided informed consent. Most patients (~88%) believed that PCI would reduce their risks of MI, whereas most cardiologists (83%) reported believing that the benefits of PCI are largely limited to symptom relief. Yet, 83% of patients reported that their questions were answered, and nearly all (96%) reported that they knew why they were having the procedure.

Is it ethical to perform a procedure (e.g., PCI) to allay a patient’s fear of an impending catastrophic event when you don’t believe the procedure reduces the risk of that event?

September 7th, 2010

Patients Still Overestimate Benefits of Elective PCI

Larry Husten, PHD

Patients who undergo elective PCI continue to overestimate the procedure’s benefits, according to a small study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine. Michael Rothberg and colleagues surveyed 153 patients and 27 cardiologists at a single academic center and found that 88% of the patients thought PCI would reduce their risk for MI and 82% thought it would reduce their risk for fatal MI. By contrast, most of the cardiologists believed that PCI’s benefits in stable patients like these would be limited to symptom relief.

In an accompanying editorial, Alicia Fernandez writes that informed consent needs to be greatly improved: “Informed consent requires us to do more than tell our patients about the risks of the treatments we offer them. We need to make sure our patients also fully understand the anticipated benefits.”

Note to readers: Rick Lange has started a discussion on this topic in the Interventional Cardiology section of CardioExchange. Click here to join the discussion.

September 7th, 2010

BMJ Papers Increase Pressure on Avandia

Larry Husten, PHD

A trio of papers in BMJ are turning up the heat on rosiglitazone (Avandia), prompting the editor-in-chief of the journal, Fiona Godlee, to say that she believes rosiglitazone “should not have been licensed and should now be withdrawn.”

The detailed investigative report by BMJ features editor Deborah Cohen reviews the long and troubled history of rosiglitazone, with a focus on the deficiencies of the European and British regulatory process. Cohen writes that “we still have no clear picture of why, after initial rejection in October 1999, the [European Medicines Agency] gave market authorisation to rosiglitazone in July 2000 in the absence of new evidence.” She also reports for the first time that in July of this year the U.K.’s Commission on Human Medicines unanimously recommended that the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) withdraw rosiglitazone from the market, but “a ‘dear doctor’ letter sent to UK doctors in July advised doctors to ‘consider alternative treatments where appropriate’.”

In an accompanying editorial, Richard Lehman, John Yudkin, and Harlan Krumholz (editor-in-chief of CardioExchange) shift some of the blame for the Avandia crisis to clinicians, noting that “we had lost sight of the main reason for treating this complex and progressive disease, which is not to reduce glycaemia but to prevent complications.” The important lesson to be learned before allowing new drugs to enter the market is that “surrogate end points are not enough, robust evidence of benefits and harms is needed.”

In an accompanying commentary, Nick Freemantle points out that to avoid problems like rosiglitazone in the future, it will be essential for regulatory agencies to require companies to provide much better data from clinical trials.

In a related development, GSK has posted the audio recording of a May 10, 2007 meeting between Steven Nissen and GSK officials. The existence of the tape, which was recorded surreptitiously by Nissen, was disclosed in February by the New York Times.

September 6th, 2010

What’s at the Heart of This Patient’s Problem?

Anju Nohria, MD and James Fang, MD

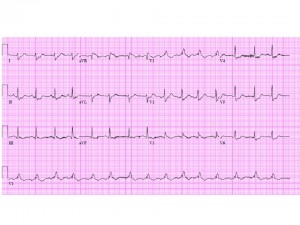

The patient is a 53-year-old lawyer with no cardiac risk factors other than a 70 pack-year history of smoking. He has a known history of diverticulitis with prior gastrointestinal bleeding and presented with lightheadedness and bright red blood per rectum. Initial evaluation revealed a drop in his hematocrit from 43% to 39%. He underwent a colonoscopy the next morning and was found to have multiple diverticula and sigmoid irritation, but no obvious source of bleeding was identified. His initial electrocardiogram is shown below.

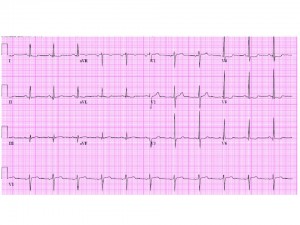

The next day, the patient abruptly bled again and had a further drop in his hematocrit to 29%, with a blood pressure of 85/50 mm Hg and a heart rate of 95 bpm. With this, the patient complained of mild chest pressure, and a repeat electrocardiogram was obtained.

The patient was seen by a surgeon, who recommended an elective partial colectomy. A pre-operative cardiology consult was obtained.

Questions:

- What is this patient’s peri-operative risk?

- Would you recommend any further cardiac evaluation prior to a partial colectomy?

- Would you recommend peri-operative beta-blockade in this patient?

Response

James Fang, MD

This gentleman has developed unstable angina in the setting of hemodynamically significant gastrointestinal bleeding. His perioperative risk is very high by any criteria. I suspect he has severe, life-threatening ischemic heart disease that has been unmasked by his acute medical condition. Although immediate resuscitation with volume and blood products should be the initial strategy, he should undergo urgent coronary angiography to define the extent of his coronary artery disease, so that therapeutic options can be reviewed. The site of his bleeding also remains unclear; once his cardiovascular status is stabilized, a tagged red cell scan or even angiography can be performed to understand the exact nature of his bleeding. Beta blockade is relatively contraindicated in someone with recently stabilized hypovolemic shock.

Part II

Anju Nohria, MD

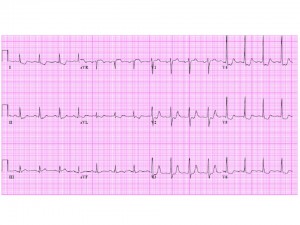

The patient was transfused with 3 units of packed red blood cells and had a follow-up hematocrit of 32%. Later that night, he became restless, removed his telemetry leads, and was found on the floor in ventricular fibrillation. He was electrically cardioverted and reverted to sinus rhythm, and an amiodarone drip was started. A post-resuscitation electrocardiogram was obtained.

The patient was hypotensive and was stabilized with norepinephrine therapy. An initial creatine phosphokinase returned at 310 U/L, with an MB fraction of 45.3 ng/mL. The troponin I was also elevated at 0.36 ng/mL. Cardiology was urgently called again.

Questions for discussion:

- What additional medical management would you recommend at this time?

- Would you take this patient to the cardiac catheterization laboratory prior to surgery?

- If a significant cardiac lesion was identified, what type of intervention would you recommend?

Response

James Fang, MD

Medical management should include volume and blood resuscitation, as well as definition of the coronary anatomy. The ventricular fibrillation and QRS widening post-resuscitation would be concerning for a large burden of CAD. In light of this patient’s life-threatening GI bleeding, the use of anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents, and even nitrates/beta-blockers is contraindicated until his coronary anatomy is defined. The management of his coronary disease depends on the nature and burden of that disease. The most critical lesion could be treated with temporizing balloon angioplasty. If there is left main and/or severe three-vessel CAD, an intra-aortic balloon pump could be used to stabilize his situation. At that point, other strategies to define his GI bleeding and subsequent therapies could be entertained.

Follow-Up

Anju Nohria, MD

The patient remained hemodynamically stable. His cardiac enzymes continued to rise, with a peak troponin I of 3.85 ng/mL, a peak creatine phosphokinase of 2667 U/L, and an MB fraction of 373.8 ng/mL. An echocardiogram revealed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 50%, with an end-diastolic dimension of 6.2 cm. He had inferior and inferolateral hypokinesis. The mitral valve appeared myxomatous, with a prolapsed anterior leaflet and a fixed posterior leaflet. There was a new posteriorly directed jet of severe mitral regurgitation.

The patient was taken to the catheterization laboratory, where he was found to have multivessel coronary artery disease with 90% left main, 90% mid left anterior descending, 80% proximal left circumflex, and 95% right coronary lesions. His left ventricular end-diastolic pressure was 12 mm Hg with large “v” waves.

He underwent surgical revascularization with a left internal mammary graft to the left anterior descending artery — and saphenous vein grafts to the first obtuse marginal and right coronary arteries. He also underwent mitral valve repair with a Carpentier-Edwards ring and plication of the anterior leaflet.

He did well postoperatively from a cardiac standpoint. He continued to be guaiac-positive but had no frank bleeding. He was discharged home on a proton pump inhibitor and no aspirin or Coumadin.

September 3rd, 2010

ESC: Similarities and Differences

Susan Cheng, MD

Many things about ESC felt different compared to other conferences I’ve attended — and as many felt the same. The basics were familiar— the welcome booths, the exhibits, and the masses of semi-serious looking people sporting the requisite badge-plus-bag accessory combo. (Thank goodness the bags were bright green and easy to spot from a mile away, saving me many a moment of disorientation while navigating the city.)

The differences weren’t quite as obvious at first. Sponsored sessions were held in the main conference venue in the late afternoons, rather than way before or after hours. There seemed to be relatively few fellows here — and very few sessions geared specifically to early-career attendees. Procedure-oriented sessions (e.g., on transcatheter aortic valve implantation) were extremely popular — I don’t know if this is because many attendees were interventionalists without other access to a transcatheter cardiovascular therapeutics conference or because general excitement around procedures is just higher overall. Part of me wonders if at least some of this interest is related to how research is done at many European centers. It took sitting down with one of my German colleagues to get a better sense of this. . . .

In all but a few countries, it seems, research can only be done during evenings and weekends — i.e., only in one’s spare time. Very few people, even in large academic centers, have truly protected time and support to do research or anything else but their clinical work. Grants are sparse and very hard to get. Industry sponsorship is helpful when available, but it is often only available in certain research areas. Even if a fellow or junior faculty member is somehow able to muster up the free time to get research done and have an abstract accepted at a conference, there is still no guarantee of funding support to cover travel costs. In such cases, one might be lucky to find outside support from a sponsor.

I realize that the perspective I got is only from one person, and different situations and circumstances probably exist. But it did give me pause. It will be interesting to see if things change over the next few years, as more regulations governing academic–industry relations are adopted across Europe and the economic climate, hopefully, improves enough to allow growth in alternate options for research support.

If anybody has any additional perspectives on this, I’d be interested to hear them. Meanwhile, my first ESC experience has left me with a lot of great food for thought — both science and non-science related.

September 1st, 2010

Clopidogrel and Aspirin Dosages Scrutinized in CURRENT-OASIS 7 Papers and Editorials

Larry Husten, PHD

In the CURRENT-OASIS 7 trial, more than 25,000 patients with ACS for whom an interventional strategy was planned were randomized to either double-dose clopdiogrel (a 600-mg loading dose on the first day followed by 150 mg daily for 6 days and 75 mg daily thereafter) or standard-dose clopidogrel (a 300-mg loading dose, followed by 75 mg daily thereafter), plus either high-dose aspirin (300-325 mg daily) or low-dose aspirin (75-100 mg daily).

In the main result of the trial, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, there was no significant difference between clopidogrel doses in the composite outcome of CV death, MI, or stroke at 30 days, but more major bleeding occurred with the double dose than with the standard dose (2.5% vs. 2.0%, P=0.01).

In a second paper, published simultaneously in the Lancet, the CURRENT-OASIS 7 investigators report on a large, prespecified substudy of more than 17,000 patients who actually underwent the planned PCI. In contrast to the main study, the substudy found a 14% reduction in the primary endpoint — from 4.5% with standard-dose clopidogrel to 3.9% with double-dose treatment (P=0.039). (In the NEJM paper, the authors state that this difference may have been due to chance.) In addition, definite stent thrombosis was reduced by 46%, from 111 events to 58 events (P=0.0001). However, major bleeding occurred more often in the double-dose group (1.6% vs. 1.1%). There were no significant differences in outcomes or in bleeding events based on aspirin assignment.

In their publication in the Lancet, the authors conclude that “a double-dose regimen of clopidogrel can be considered for all patients with acute coronary syndromes treated with an early invasive strategy and intended PCI.” However, in an accompanying comment, Gregg Stone notes that there was no difference in mortality at 30 days and writes: “Presumably, any benefits from reduced ischaemic complications in reducing mortality were offset by increased rates of major bleeding with double-dose clopidogrel. A reduction in major ischaemic complications must be achieved without increasing overall bleeding, or vice versa, to further reduce mortality with antiplatelet and antithrombotic agents. The likelihood of achieving such a balance might be increased by considering individual patient’s risks for ischaemia versus bleeding.”

In an NEJM editorial, Valentin Fuster makes several recommendations and observations. Noting the lower rates of minor bleeding with low-dose aspirin, he writes that “it is time for the proponents of higher-dose aspirin to concede defeat and modify clinical practice.” Fuster also recommends a 600-mg loading dose of clopidogrel, but writes that “there appears to be no role for the routine double dosing of clopidogrel in the subsequent 6 days, particularly in light of the higher rates of major bleeding.”

Fuster also expresses concern stemming “from apparent discrepancies between the reporting of the trial at the annual meeting of the European Society of Cardiology in 2009 and the publication of the trial findings 1 year later in the Journal. During the hotline presentation at the meeting, it was concluded that the use of double-dose clopidogrel significantly reduced major cardiovascular events in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. It is clear that this conclusion differs from that of the current article, which reports that the trial failed to demonstrate superiority of double-dose clopidogrel over standard dosing for the reduction of cardiovascular events in the interventional subgroup. The conclusions reported at the meeting led many cardiologists to adopt the double-dose clopidogrel strategy, thus leading to more clopidogrel being prescribed. This outcome underscores the need for simultaneous publication of high-impact clinical trials when they are presented at international meetings.”

—