April 28th, 2011

U.S. Cardiologists Report $325,000 Median Compensation in Survey

Larry Husten, PHD

Cardiologists were the third-highest-paid physician specialists in 2010, according to a survey of more than 15,000 physicians conducted by Medscape, including a detailed report on the approximately 475 cardiologists in the survey. The cardiologists reported a median compensation of $325,000. Only orthopedic surgeons and radiologists, at a median of $350,000, topped the cardiologists. One-fifth of cardiologists said they made more than $500,000.

Almost half of cardiologists reported making as much money in 2010 as in 2009, but about a third said that their income declined rather than increased in 2010. More interventional cardiologists than preventive cardiologists reported a decline in earnings. The report attributed this difference to cuts in Medicare reimbursement for cardiology procedures and tests and increases for patient visits.

Male cardiologists earned significantly more than female cardiologists ($340,000 vs. $249,000). The report provides many additional details about variation in compensation according to geographical location and practice setting.

Forty-six percent of cardiologists surveyed said they were fairly compensated, 66% said they would choose medicine again as a career, and 75% said they would choose the same specialty.

A prior survey from the Medical Group Management Association reported very high starting salaries and recruiting bonuses for new cardiologists, while a study in Health Affairs found an overwhelming lifetime advantage in wealth accumulation for cardiologists and other highly paid specialists over other physicians.

April 27th, 2011

Large Meta-Analysis Finds No Link Between ARBs and MI Risk

Larry Husten, PHD

Angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) don’t increase the risk for MI, according to a large new meta-analysis published in BMJ. Concerns about ARBs and MI have lingered since the VALUE trial in 2004 found a 19% increase in the risk for MI, though subsequent trials have not reinforced the finding.

Sripal Bangalore and colleagues combined data from 37 randomized trials including more than 147,000 patients and found no increase in MI risk associated with ARBs when compared with controls (relative risk 0.99, CI 0.92-1.07). The authors wrote that the study provides “firm evidence to refute the hypothesis that angiotensin receptor blockers increase the risk of myocardial infarction (ruling out even a 0.3% absolute increase).” Increases in death or cardiovascular death were similarly ruled out. Furthermore, the researchers found that ARBs were associated with significant reductions in the risks for stroke, heart failure, and diabetes.

April 27th, 2011

Scrubs and Sandwiches- A Deadly Combination?

David Martin, M.D.

I was enjoying lunch at a popular midtown Sacramento restaurant recently, when two patrons walked in wearing green scrubs. Both were wearing official badges from a large, local hospital, revealing one to be a physician, the other a registered nurse. Concerned that these scrubs may have been exposed to antibiotic-resistant bacteria, I politely asked that the healthcare workers leave the restaurant, and return only in regular attire. Both were mildly annoyed but agreed to depart. I took this action because I believe the use of scrubs in the community is a serious and avoidable public threat. I am also convinced that simple public action can play a powerful role in effecting change and that the healthcare community has been remiss in addressing this issue. I am also hopeful that this action will encourage healthcare organizations and providers to take this issue more seriously, and to address it less equivocally from within their own organizations.

Scrubs are generally worn and laundered inside hospitals, in part to keep dangerous pathogens from colonizing the community at large. Such pathogens include the antibiotic-resistant superbugs, such as Clostridium difficile (C. Diff.), Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE).

The Infectious Diseases Society of America reports that community-acquired C. Diff. infection is on the rise, and speculates that environmental exposure to this pathogen may be partly to blame. So why would hospital personnel carelessly transport it from hospitals to the community at large? MRSA-related morbidity and mortality used to be seen almost exclusively in hospitalized patients, but now occurs more frequently in the general population, even among those who have not had hospital exposure. And it has also been demonstrated that healthcare professionals who enter a hospital room occupied by a MRSA-infected patient will frequently acquire MRSA on their clothing, without actually touching the infected patient. Yet some healthcare workers choose to move about routinely in scrubs, between hospitals and coffee houses, restaurants, and local shops, where they may spread dangerous organisms to tables, dinnerware and a multitude of items that are subsequently handled by many others. Furthermore, these superbugs are not eliminated by routine cleaning products, and survive on ordinary surfaces for weeks to months, where many others can pick them up unknowingly.

I acknowledge at the outset, this is a controversial issue. Some will argue that the use of hospital-exposed scrubs in public has never been proven as the proximate cause of a single infection. Yet this is not the type of study that can be done, ethically or practically – recall the Tuskegee Syphilis Study as an extreme example – which is why prudence, along with inferential decision making, is necessary. Since we cannot subject a study population to superbugs under the controlled conditions necessary to “prove” a connection, we are forced to create policy based on common sense. It should hardly require complete proof to connect these dots.

I am also addressing what has become policy at many institutions, yet many providers have trivialized the need for compliance or ignored the policy altogether. This lack of respect for decisions that are made consensually by the greater medical community, and (as a physician) the very institutions that make our practices possible, is unprofessional and irresponsible. As other physicians have agreed elsewhere, this in itself undermines the respect of those who depend on us for healthcare services. The two individuals I encouraged to leave the restaurant are case in point. Both, as I later learned, came from a hospital that does not allow hospital scrubs outside of patient-care areas.

While I am now advocating direct confrontation (see my posts at reportingonhealth.org), I do so largely because physicians, hospitals and healthcare safety organizations have failed to address the scrubs issue. Physicians are quick to raise the red flag when policy is thrust upon them, so why not be more proactive and give this issue the attention it is due? The AMA News reported that Washington State Representative Tom Campbell addressed the rising MRSA-related infection issue by introducing a bill and stated, “If hospitals won’t take meaningful steps to stop drug-resistant infections, then we’ll pass legislation to make sure they do.” How many readers of CardioExchange welcome this brand of change through legislation? I would prefer a more proactive approach among those most qualified to study this issue and render sound policy guidelines, and greater compliance by those who feel they are above the rules.

Let me refer to another practice concern, in which noncompliance has been “proven” to cause harm. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) has launched a bold initiative called “Speak Up,” which encourages individuals to take an active role in reducing our risk of infection by assuring that providers wash their hands and wear gloves. JCAHO has even published a coloring book for children, to teach, early in life, that it is not disrespectful or inappropriate to speak up and remind physicians and other providers to take appropriate safety measures. For adults, the Joint Commission issues buttons, to be worn by healthcare providers, which say, “Ask me if I’ve washed my hands.” This initiative is supported by the American Hospital Association and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, among many other quality and safety organizations. Some hospitals and clinics that have embraced and enforced rigorous hand washing protocols have reduced their rate of institution-acquired infections, in some cases quite dramatically. Yet, believe it or not, many healthcare workers have not complied with institutional policy on hand washing. While JCAHO is hardly perfect, doesn’t it ring alarm bells when patients are being taught to enforce proper hygiene because healthcare providers have been remiss? Yet until and unless we take greater responsibility ourselves, I support this effort and encourage more of its kind.

Most area hospitals have official or unofficial policies, which restrict the use of hospital scrubs to surgical suites and related patient-care areas. Exposure to superbug-infected patients mandates a change of scrubs before moving on to care for others. Wearing them or laundering them outside of the hospital is forbidden or discouraged, but enforcement of such policy is a difficult task. I spoke about this concern with quality assurance personnel at two of the four major hospital organizations in my home, the Sacramento area. The two others failed to return several calls. One of the quality assurance staff members shared an observation that her organization had been effective in curtailing scrub misuse by non-physician staff, but that physicians were frequently allowed to break the rules. She said that many considered themselves to be “above the law” in this regard. Some travel to and from their own homes in contaminated scrubs, which suggests that this practice stems less from a disregard for others and more from a curious type of denial and disbelief that hospital-contaminated scrubs offer any real threat. Are these the same professionals who have resisted aggressive hand-washing protocols, which make a huge difference in institutional infection rates? As a physician who has spent most of my career in the surgical suite, I find this perplexing.

The notion that physicians and nurses are immune to error, or unapproachable regarding its potential should have been laid to rest long ago. None of us should share public space with those who unnecessarily risk compromising public safety, knowingly or otherwise. I believe, as does the medical community at large, that it is time for all of us to take responsibility for our health and safety, rather than displacing the entirety of this onus to our caregivers. Purging public spaces of hospital-exposed garments could make more than a public fashion statement. It could reduce illness and even death from infectious disease.

It has been credibly estimated that over 100,000 deaths occur each year in the US from preventable medical mistakes. It has also been observed that such high mortality would never be tolerated in the airline industry, which falls under intense scrutiny for mishaps resulting in tens or hundreds of deaths. Granted, the airline analogy only goes so far, but why should there be a difference in transparency between these two industries, both of which exercise control over our safety? Most of us feel quite safe when we fly, even in these turbulent times, but I think most people would speak up if they noticed a public danger while boarding an airplane. So why shouldn’t anyone voice concern when they see a threat to our health? Public accountability and trust are not incompatible in the airline industry; why should they be at odds in healthcare?

So how can people effect change? Perhaps most people would consider it too forward to actually ask someone to leave a public place. For those who do feel comfortable doing so, however, I think it is an entirely reasonable approach. I strongly believe that most healthcare workers will comply with such a request, and that future transgressions will be reduced as violators learn of the concern among those around them.

For those few who do not comply with such requests or who do not engage in reasonable conversation, people should walk away without confrontation. I have advocated that they call the institutions where those in scrubs are employed or in practice, insisting on the attention of a hospital administrator, president or chief executive officer to explain the concern that medical staff may be introducing potentially dangerous bacteria into the public spaces that everyone shares.

This essay will surely offend some readers. Some may be concerned that my approach may cause undue fear, though I believe the pathogens themselves are of greater concern. Others may simply believe that scrubs do not represent a real risk. And perhaps others will feel that healthcare policy is not in the purview of the public. I hope to establish dialogue on this topic, which is almost always a signpost on the road of quality improvement. But let us also abide practices that are known to be safe, and exercise restraint with those in doubt. Washing hands and changing clothes are small precautions to take.

April 26th, 2011

Drug-Eluting Stents Add Nearly $1.6 Billion per Year to Medicare Costs

Larry Husten, PHD

Drug-eluting stents (DESs) cost Medicare an additional $1.57 billion per year, according to a study published online in the Archives of Internal Medicine. Using a random sample of Medicare beneficiaries, Peter Groeneveld and colleagues compared annual costs for patients with coronary artery disease in 2002 (the year before DESs were introduced) with costs from 2002 through 2006.

The researchers then calculated the difference in national expenditures attributable to DESs and found that for each CAD patient (whether or not they received a DES), DESs were associated with a:

- $657 cost increase in patients with acute MI,

- $999 increase in patients with noninfarct ACS,

- $146 increase in patients without any ACS.

On a national level, the annual increase in Medicare costs attributable to DESs totaled $1.57 billion:

- $236 million for acute MI,

- $269 million for noninfarct ACS,

- $1.067 billion for non-ACS CAD.

Because patients without ACS were by far the largest population, the researchers noted that this group accounted for more than two-thirds (68%) of the increase in cost, “suggesting that DES use among patients without ACS was particularly cost amplifying (ie, DES introduction changed patterns of care for patients without ACS in a more costly manner than for patients with ACS).” The researchers commented: “This is troubling, since the limited efficacy of percutaneous coronary intervention among patients with ACS, whether or not DESs are used, would not justify sizeable DES-related cost increases among patients without ACS.”

In an editor’s note, Rita Redberg wrote that “it is time to clearly define what the value of this extraordinary investment has been in terms of patient benefits and study the harms and determine if we are getting good value for this outlay.”

April 26th, 2011

FDA Briefs: New Stent Approved, Advisory Committee Meeting on ACCORD Lipid

Larry Husten, PHD

Boston Scientific said on Monday that it had received FDA approval for a third-generation drug-eluting stent, the ION Paclitaxel-Eluting Platinum Chromium Coronary Stent System. The “unique platinum chromium (PtCr) alloy” is specifically designed for use in the coronary arteries.

The FDA announced that the Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee would meet on May 19 to discuss the ACCORD Lipid trial. According to the FDA agenda:

The results of the ACCORD Lipid trial indicated that there was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of clinical trial subjects treated with simvastatin plus placebo [versus] simvastatin plus fenofibrate who experienced a major adverse cardiac event. In a prespecified subgroup analysis from the ACCORD Lipid trial, there was an increase in the proportion of female trial subjects treated with simvastatin plus fenofibrate versus simvastatin plus placebo who experienced a major adverse cardiac event. The clinical significance of this finding is unclear. An additional safety concern associated with the use of fenofibrate plus simvastatin, or any other statin, is muscle toxicity.

April 25th, 2011

ACC and AHA Publish Expert Consensus Document on Hypertension in the Elderly

Larry Husten, PHD

Although 64% of elderly men and 78% of elderly women have hypertension, this was not considered a significant clinical problem until 2008, when the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET) trial demonstrated the substantial benefits of reducing blood pressure in these patients. Largely in response to HYVET, the ACC and the AHA have published the first expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly.

“Treating hypertension in the elderly is particularly challenging because they usually have several health problems and a greater prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and cardiac events,” said Wilbert Aronow, one of the chairs of the ACC/AHA writing committee, in an ACC press release. “There also needs to be greater vigilance to avoid treatment-related side effects such as electrolyte disturbances, renal dysfunction, and excessive orthostatic blood pressure decline.”

Because so many trials have excluded elderly patients, much of the document relies on expert consensus rather than data from clinical trials. Although the treatment goal for uncomplicated hypertension is defined as <140/90 mm Hg, this goal has not been validated in the elderly population. Additionally, it is unclear whether target systolic blood pressure should be somewhat higher in patients over 80 years of age.

Antihypertensive therapy, according to the document, should be selected based on efficacy, tolerability, specific comorbidities, and cost. Drugs should be started at the lowest dose and increased gradually. The document recommends lifestyle changes for patients, including regular physical activity, salt restriction, weight control, smoking cessation, and avoiding excessive alcohol intake.

April 22nd, 2011

Diet and Cardiovascular Health: What’s the Bottom Line?

Eric Rimm, ScD

CardioExchange welcomes Dr. Eric Rimm, Sc.D., the director of the Program in Cardiovascular Epidemiology at Harvard School of Public Health and a member of the USDA’s 2010 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Dr. Rimm answers Associate Editor Susan Cheng’s questions about the DGAC’s 2010 report. We welcome you to offer your own questions and opinions.

Background: The 2010 USDA guidelines take a strong position on reducing overall calorie consumption and increasing physical activity as the foundation of ensuring optimal nutrition in a population with a majority of overweight and obese adults and a rapidly growing proportion of overweight and obese children. Specific dietary recommendations for achieving these goals focus on increasing consumption of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, fat-free and low-fat dairy products, and seafood; and on reducing consumption of sodium, saturated and trans fats, added sugars, and refined grains.

Cheng: What would you highlight as the key take-home message(s) from the new USDA guidelines that clinicians should communicate to their patients?

Rimm: As you know, the 13-member scientific committee was just an advisory committee: The USDA and HHS wrote the final guidelines. However, many of the points in our advisory report were carried through to the final guidelines. We wanted them to be focused as much as possible on the total diet and not overly focused on one specific aspect such as the fat content or the potassium content (as examples). It is clear that this country is gaining too much weight, which is due to an imbalance between calories in and calories out; so a healthy diet is important, but there is no question that regular exercise is a crucial component, too.

In general, a complete diet should have plenty of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, healthy sources of protein such as fish, poultry, legumes, and low or nonfat sources of dairy. The data are quite clear that individuals should not focus on the total fat content of their diets but, rather, aim for diets low in saturated fat and refined grains.

Cheng: The salt restriction recommended in the guidelines generated some controversy. Was it difficult for the group to reach consensus on this topic? How should physicians counsel patients around salt in particular?

Rimm: Interestingly, among the scientific advisors around the table, there was quite a clear consensus that the target should be 1500 mg/day. However, the final government report was more forgiving and had a cutoff of 2300 mg for some people and 1500 mg for high-risk individuals (aged >50, African Americans, or with existing health conditions). Many reasons were given for the difference, but in general more leniency was reported because of concern that the food industry would not be able to produce processed foods lower in sodium. Docs should counsel all patients to lower sodium and to be wary (read the labels) of processed foods, store-baked foods, and especially ready-made meals in the freezer and deli section and at restaurants. Most of the sodium we get every day has nothing to do with how much salt is added at the table and much more to do with how much is stealthily put into prepared/processed foods.

Cheng: There has been a lot of recent interest in the lay media about detrimental health effects of sugar consumption. To what extent do you think this is backed up by evidence?

Rimm: The evidence continues to mount on the adverse health effects of added sugar. It is true that sugar is just a carbohydrate source that, like others, is readily absorbed and converted into fat for storage. Unfortunately, added sugars like high-fructose corn syrup are so cheap that the food industry can put it into everything; so, even when consuming small amounts, we all get more calories than we need. Just one added 12-oz soda a day (145 kcals) can lead to substantial weight gain over a year if it is not burned, or if other aspects of the diet are not reduced. Since many of these types of foods (e.g., soda) are consumed quickly and do not affect satiety, the evidence shows that they lead to weight gain and increase risk for diabetes.

April 21st, 2011

CDC: Half the U.S. Now Protected by Comprehensive Smoke-Free Laws

Larry Husten, PHD

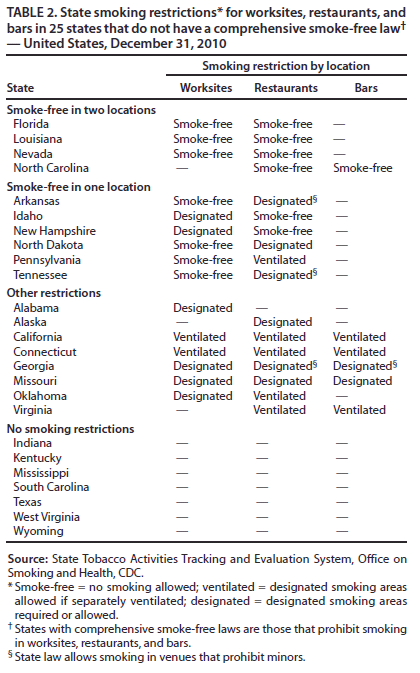

According to a CDC analysis in MMWR, nearly half the U.S. population is now protected from second-hand smoke by comprehensive laws that restrict smoking in three venues (private sector worksites, restaurants, and bars). If the current trend continues, all 50 states and the District of Columbia will be smoke-free by 2020.

The first [statewide] law prohibiting indoor smoking was passed in Delaware in 2002. Today, 26 states in the country have comprehensive smoke-free laws. In addition, 10 states have laws that restrict smoking in one or two (but not all three) venues, and eight states have less restrictive laws allowing smoking in designated areas or areas with separate ventilation. Seven states have no smoking restrictions. The south has lagged behind the rest of the country in enacting smoke-free laws.

“The progress made during the past decade in enacting comprehensive state smoke-free laws is an extraordinary public-health achievement,” write the CDC authors.

“Secondhand smoke is responsible for 46,000 heart disease deaths and 3,400 lung cancer deaths among nonsmokers each year,” said the CDC’s Ursula Bauer, director of the CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, in a press release. “Completely prohibiting smoking in all public places and workplaces is the only way to fully protect nonsmokers from secondhand smoke exposure.”

April 21st, 2011

Will a STICH in Time Save Nine?

Anju Nohria, MD and James Fang, MD

A 57-year-old man with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and smoking presented with increasing dyspnea on exertion, mild chest discomfort, and lower-extremity edema. Physical exam results were consistent with decompensated heart failure.

Echocardiographic findings:

- left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), 20%

- LV end-diastolic dimension, 6.3 cm

- global hypokinesis (with regional variation affecting the septum, inferior wall, and apex most severely)

- mildly enlarged right ventricle with moderately reduced function

- mitral annular dilatation with at least moderate mitral regurgitation

- moderate tricuspid regurgitation (estimated pulmonary-artery systolic pressure, 30 mm Hg + right-atrial pressure)

An evaluation for the cause of new-onset cardiomyopathy included a left-heart catheterization that revealed 60% left-main disease and an 80% proximal right coronary artery lesion.

Subsequent myocardial perfusion imaging (with Regadenoson positron-emission tomography) revealed a medium-size perfusion defect throughout the inferior and basal inferoseptal walls with moderate reversibility and a small reversible perfusion defect in the LV apex. The patient’s summed stress score (scar + ischemia) was 11; the summed difference score (ischemia) was 4. His resting LVEF was 16%, with an end-systolic volume index of 96 mL/m2. His post-stress LVEF was 18%, with an end-systolic volume index of 100 mL/m2.

The patient was treated with intravenous diuretics and was started on aspirin and a statin. Once he was euvolemic, a low-dose ACE inhibitor and beta-blockers were added. Amiodarone was started after monitoring revealed several runs of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia.

A right-heart catheterization after medical optimization revealed right-atrial pressure of 4 mm Hg, pulmonary-artery pressure of 41/19 mm Hg, and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure of 13 mm Hg. Pulmonary-artery saturation was 66%, with a calculated cardiac output of 3.1 L/minute and a cardiac index of 1.65 L/minute/m2.

Questions:

1. Would coronary revascularization benefit this patient? If so, would you recommend that he undergo surgical revascularization specifically?

2. Do findings from the recently published STICH trial influence your assessment? If so, how?

3. If you proceed with surgery, should it be performed at a ventricular assist device/transplant center?

Response

James Fang, MD

This gentleman has received appropriate care up to this point. I would have taken the same approach. If he remains symptomatic (particularly with angina), revascularization can be offered. In some centers, multivessel/left main PCI could even be entertained. It should be pointed out that this patient would not have been eligible for STICH because of the left main disease. However, the overall approach remains consistent with the STICH trial in that patients crossed over from medicine to surgery if it was felt to be clinically necessary. I generally favor the performance of high risk procedures or surgeries in places where advanced support can be offered.

One final comment: the hemodynamics are a bit curious. The calculated cardiac output is relatively low for that pulmonary artery saturation suggesting that either the hgb concentration was very high or the oxygen consumption used in the calculation may not have been accurate.

Follow-Up

Anju Nohria, MD

The patient was thought to have a combined ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Given his low ejection fraction and left-ventricular dilatation, he was considered to be a high-risk candidate for surgical revascularization without clear expectation of benefit. Therefore, he was medically managed and evaluated for cardiac transplantation.

The only notable finding on the patient’s initial evaluation for transplant was continued tobacco use, and listing for transplantation was deferred until he could demonstrate abstinence from smoking for at least 6 months. His initial peak oxygen uptake was 7.4 mL/kg/minute at an adequate work load. After close follow-up and gradual up-titration of his ACE-inhibitor and beta-blocker dosing, peak oxygen uptake had increased (9 months later) to 13 mL/kg/minute.

The patient continues to exhibit NYHA class III symptoms, and his consent for listing as a Status 2 transplantation candidate is now being sought.

April 20th, 2011

New WHI Analysis Links Calcium Supplements to CV Risk

Larry Husten, PHD

A new analysis may renew concerns that the combination of calcium supplements and vitamin D might increase cardiovascular risk. The link has been proposed before, but the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) found no additional risk. Now, however, in an article appearing in BMJ, Mark Bolland and colleagues point out that more than half the 36,000 women in the WHI were taking calcium supplements at the start of the trial.

In a reanalysis of data from the 16,718 WHI participants who were not taking calcium supplements at the trial’s start, the investigators found a 16% increase in the risk for MI and stroke in the group randomized to calcium supplements and vitamin D compared with placebo (P=0.05). A meta-analysis combining the new WHI data with data from previous trials turned up a similar pattern of increased CV risk associated with calcium supplements. The authors did not find a dose-response relationship between calcium supplements and CV risk. They speculate that “the abrupt change in plasma calcium concentration after supplement ingestion causes the adverse effect, rather than it being related to the total calcium load ingested.” They conclude that “a reassessment of the role of calcium supplements in osteoporosis management is warranted.”

However, in an accompanying editorial, Bo Abrahamsen and Opinder Sahota write that “insufficient evidence is available to support or refute the association.” They write that further studies are needed to resolve the ongoing debate.