July 1st, 2011

Rivaroxaban (Xarelto) Gains First FDA Approval for DVT Prevention

Larry Husten, PHD

Rivaroxaban (Xarelto, Janssen) received FDA approval today for the prevention of deep-vein thrombosis in patients undergoing knee or hip replacement surgery. This oral anticoagulant has been approved for use at a 10-mg dose, once daily, for 35 days following hip replacement and for 12 days following knee replacement surgery.

The company has also submitted an application for the broader indication of the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in AF patients.

July 1st, 2011

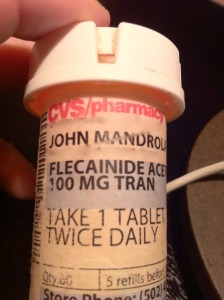

AF Update: Flecainide Misinformation

John Mandrola, MD, FACC

John Mandrola is a cardiac electrophysiologist and blogger on matters medical and general. Here is a recent post from his blog, Dr John M.

I have said that the best tool for treating atrial fibrillation (AF) is education. I still strongly believe that, perhaps more than ever.

AF presents itself to people in so many different ways – from no symptoms to incapacitation. Likewise, the treatments for AF range from simple reassurance and lifestyle changes, to taking a medicine, and on to having [a] complex ablation[s].

Because knowledge is so important to patients with AF, I encourage them to do outside research. This surely means going online. The problem, of course, comes with assessing the quality of information. It reminds me of what an old professor used to profess: “No data is better than bad data.”

What’s more, the vast diversity of AF makes comparing notes with friends problematic. One person’s wonder drug may be another’s poison.

Last week, this provocative AF headline came through on one of my Google Alert emails:

“Flecainide Treatment Linked to Sudden Cardiac Death”

The story originated from HealthDay News and was carried by many other health-related sites. It was even posted on the Facebook page of the prestigious Heart Rhythm Society.

Whoa, I wondered to myself, how had I missed such an important development? The potent heart rhythm drug, flecainide, is one that I recommend frequently. I have even taken it myself.

But then I looked past the headline to the actual journal article. The study was published in the low-impact Journal of Internal Medicine.

The single-center Swedish study looked back at a mere 112 patients with AF who had taken flecainide between 1998 and 2006. They reported that three middle-aged patients died suddenly; two of the three had autopsy-proven heart attacks from typical coronary obstructions. They also reported that another seven patients suffered nonfatal heart rhythm problems related to flecainide – medical people call this proarrhythmia.

So far, there is nothing newsworthy, or even publishable, in the article. We already know that AF drugs can sometimes make the heart rhythm worse. That two of 112 middle-aged patients died of heart attack is also not surprising. Heart disease is our number one killer.

The researchers then did something very misleading: They compared the event rates of their tiny population of flecainide-treated patients with “matched” controls in the general population of Sweden. The problem, of course, is that matching the groups is impossible.

They then went on to incorrectly conclude: “Our findings indicate that SCD or proarrhythmia might occur [with flecainide], even in a relatively healthy AF population.”

The final straw of this highly flawed study came when I had our librarian print the actual article. In the disclosure section, it turns out that two of the researchers receive support from Sanofi-Aventis, the makers of Multaq, a controversial AF drug that competes with flecainide.

So in summary, here is an obscure medical journal that publishes a tiny look-back study that makes erroneous comparisons and purports false conclusions. But none of this stops its propagation on health-related social media. Not one of the health sites with the scary headline mentioned prior trials that have demonstrated the safety of widely prescribed flecainide. In contrast, here is a study (of more than 114,000 patients with AF) that highlights the safety of flecainide.

There is a lot about our information revolution that is fantastic. I would never want to go back to using index cards and putting nickels in copy machines. But…

My take-home message: When studying health information, always read the fine print. Understanding the actual science cannot be underestimated.

JMM

P.S. The purpose of this piece is not to advocate one AF drug over another. Like anything else in medicine, AF treatment should occur in the setting of a doctor-patient relationship.

June 30th, 2011

Advice for New Cardiology Fellows — Part 3: Subspecialization

John Ryan, MD, Andrew M. Kates, MD and James De Lemos, MD

With July just around the corner and a new generation of cardiologists about to start their training, the CardioExchange editors have asked the fellowship moderators to share their advice about how to face this exciting new challenge. Our third and final installment of this series focuses on subspecialization.

Do fellows need to have an idea of what they want to subspecialize in when they get started?

John Ryan (current fellow): I don’t think so. Most of us have not done catheterizations or read echos before starting fellowship, and not many of us appreciate what it means to be an EP or a heart failure doctor until the clinical training starts. Therefore, I think people should go in with an open mind. In fact, I feel it may affect the general training if one starts the fellowship with the intention of entering one particular area of cardiology.

Andy Kates (fellow from 1997 to 2001): Many clinical fellows come in with their long-term plans already in place (heart failure, EP, interventional) because of exposure (albeit somewhat limited at times) during their residency. While quite a few stay the course, others change focus during their fellowship as they see the various areas of cardiology in a different light than they did during residency. That is one of the reasons why the experiences of the first clinical year are so diverse and our fellows rotate through every (or nearly every) area of cardiology.

James de Lemos (fellow from 1996 to 1999): I agree with John and prefer that fellows not come in “hard wired,” because it leads to closed minds. I want the fellows to treat every rotation as if it might be their future calling.

What if there are rotations you’re not good at?

Ryan: One of the biggest struggles is the procedural aspect of cardiology. We typically go through medical school and residency being very cerebral and administratively oriented. Cath requires a new hands-on skill set, and I feel that the procedures we do during residency don’t prepare us for this (putting in a femoral venous line is nothing compared with getting the JR-4 to turn into the RCA under fluoro). Cath requires all of your senses, and I found it demoralizing when I struggled. The most important thing is not to avoid these tough rotations but to work extra hard during them. Getting to spend time in the cath lab is a privilege. A few years from now when we are out of fellowship and in our subspecialties, we won’t have the opportunity to work with teachers in the lab or learn our skills under supervision. Spending a couple of extra hours in those first few weeks practicing with the manifold or patiently “clocking” a JL-4 catheter inside and outside the body will pay off. It will make you a lot more comfortable and confident on-call, as well as help you feel more like a card-carrying cardiologist with skills that set you apart from all the other specialties.

Kates: It is interesting to see in which rotations different fellows excel. Although there are always a few fellows who seem able to handle any rotation equally well, most are drawn to one area or another — usually related to the reason why they chose cardiology in the first place. While that aptitude may be most obvious in the procedural areas, it may be equally apparent in other areas: the consultative cardiology realm, where interactions with patients and various clinical services requires a unique skill set; and in research, be it basic science, translational, or clinical research, where a certain creative mind-set is essential to asking — and answering — questions.

I agree with John that our role as PDs is to guide trainees to where their natural strengths are, but also to encourage fellows to reach higher and realize that hard work helps to build strengths as well.

de Lemos: We all have strengths and weaknesses, and some things just come easier or harder for different people. I agree with John that this is most obvious on procedural rotations, but we also see it with interpreting images and dealing with complex data on cognitive rotations. It’s important use fellowship to not only find out what areas of cardiology you like the best, but also those that you have the most natural aptitude for. In general, our job as program directors and attendings is to provide honest feedback to fellows about skills and talents in particular areas, to help guide them toward a career path that matches their natural talents. Having said that, I believe that “natural talent” with your hands is not as important to procedural subspecialties as it was a few decades ago, given maturing of the fields and improvement in technology.

Even on procedural rotations, your attendings will care much more about your professionalism, your detailed workup of patients, and your effort than they will about whether you have “great hands.”

What are your thoughts about the challenges of subspecialization within a cardiology training program? And please also share what you thought of this three-part “advice” series.

June 28th, 2011

Diastolic Dysfunction Linked to Mortality

Larry Husten, PHD

A new study sheds light on the prognostic value of diastolic dysfunction (DD) in patients with normal systolic function. In a study published in the Archives of Internal Medicine, Carmel Halley and colleagues reviewed echocardiograms from 36,261 consecutive patients who were found to have normal systolic function. Nearly two thirds (65.2%) had some degree of DD.

There were 5789 deaths during 6.2 years of follow-up. The greater the degree of diastolic dysfunction, the higher the mortality rate:

- normal diastolic function: 7% mortality

- mild DD: 21% mortality

- moderate DD: 24% mortality

- severe DD: 39% mortality

In a separate analysis using propensity matching, only moderate and severe DD were significantly associated with mortality.

In an invited commentary, Ileana Piña writes that the study provides important new information about DD, informing physicians that DD is common and that physicians should “be aware of the prognostic value of moderate and severe DD.” But the study does not appear to shed light on the large group of elderly women who present with acute heart failure, she writes.

June 27th, 2011

TAVI: Playing in the Sandbox Together

Richard A. Lange, MD, MBA and L. David Hillis, MD

Kudos to the the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF) and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) for getting ahead of the game by rolling out a joint position statement regarding transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) before the FDA panel convenes in July to consider approval of the procedure. It’s a terrific first step to avoid some of the “tugs of war” that have characterized previous transformational technologies.

Here’s what they’re recommending:

- Specialized regional heart centers (with expertise and high volumes of valve procedures)

- “Heart teams” (composed of primary cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, interventionalists, echocardiographers, imaging specialists, and heart failure specialists)

- Standardized protocols for training physicians on how to use this therapy appropriately

- Modified cath labs or hybrid operating rooms (large rooms capable of state-of-the art angiographic imaging and valve surgery).

- National registries for post-market practice treatment outcomes

- Studies to determine if patients who are younger and lower-risk than those in current randomized trials will benefit from the procedure

This consensus statement aligns the interests of various expert physicians (e.g., cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, interventionalists, heart failure physicians, and imaging specialists) and professional societies to deliver the best possible patient-centered care.

Has your center adopted a “Heart Team” approach to coronary revascularization or valve surgery?

June 27th, 2011

Asprin Dosage in U.S. May Explain Disparity in Ticagrelor Results in PLATO

Larry Husten, PHD

Although the PLATO trial demonstrated the overall superiority of ticagrelor (Brilinta, AstraZeneca) to clopidogrel in more than 18,000 acute coronary syndrome patients worldwide, approval of the drug in the U.S. has been delayed because of ticagrelor’s lack of effect in the prespecified subgroup of patients from North America. Now, two analyses of the trial, presented at the American Heart Association’s Emerging Science series (a new peer-reviewed venue from the AHA), suggest that the North American findings may be the result of more use of high-dose aspirin in U.S. patients.

Ken Mahaffey presented the results from the analyses, which were performed by the Duke Clinical Research Institute and AstraZeneca. The analyses were not able to rule out chance as an explanation for the results in the North American subgroup, but did show that high-dose aspirin (≥300 mg/day) was used far more often in the U.S. than in the rest of the world (53.6% vs. 1.7% of patients).

Mahaffey reported that in patients taking low-dose aspirin, outcomes were better in the ticagrelor group than in the clopidogrel group. The difference was statistically significant in the rest of the world but not in the U.S.:

- For high-dose aspirin in the U.S., the hazard ratio for CV death, MI, or stroke with ticagrelor was 1.62 (CI 0.99-2.64).

- For patients taking low-dose (≤100 mg/day) aspirin in the U.S., the HR with ticagrelor was 0.73 (CI 0.40-1.33).

- For patients taking high-dose aspirin outside the U.S., the hazard ratio with ticagrelor was 1.23 (CI 0.71-2.14).

- For patients taking low-dose (≤100 mg/day) aspirin outside the U.S., the HR with ticagrelor was 0.78 (CI 0.69-0.87).

In an AHA press release, Mahaffey said that “physicians choosing to use ticagrelor in countries where it is approved and available should consider using a low-dose of maintenance aspirin with the drug.”

June 25th, 2011

Limited Benefit Found for Early Aggressive Management of Diabetes

Larry Husten, PHD

In the ADDITION-Europe trial, 3055 patients without diabetes were randomized to either routine care or screening followed by intensive treatment of multiple risk factors. The results were presented at the American Diabetes Association meeting and published online in the Lancet. After five years, cardiovascular risk factors — HbA1c, lipids, and blood pressure — were “slightly but significantly better in the intensive treatment group,” according to the authors. However, the primary endpoint of the study, incidence of the first cardiovascular event, did not differ significantly between the groups, although the difference favored intensive treatment: 7.2% in the intensive-treatment group versus 8·5% in the routine-care group (hazard ratio, 0·83; 95% CI, 0·65–1·05). All-cause mortality was 6·2% versus 6·7% (HR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0·69–1·21).

The authors speculated that the results may be due, in part, to overall improvements in risk factors over the course of the trial, resulting in fewer cardiovascular events than expected. In addition, longer follow-up might be required to demonstrate a significant benefit. The authors concluded that “the extent to which the complications of diabetes can be reduced by earlier detection and treatment remains uncertain.”

In an accompanying comment, David Preiss and Naveed Sattar write that “the emergence of evidence-based standards of routine diabetes care, especially for lipid-lowering and antihypertensive therapies, negated potential benefits of intensive therapy in ADDITION-Europe. The key questions now are whether a sizeable reduction in the lead time between diabetes onset and clinical diagnosis can be achieved by implementation of simpler diagnostic criteria (i.e.,HbA1c) and, if so, to what extent this development might further reduce cardiovascular and mortality risks in patients with diabetes.”

June 25th, 2011

Diabetes Growth Termed a Rising Global Hazard

Larry Husten, PHD

In 2008, some 347 million people in the world had diabetes, more than twice the 153 million in 1980, according to estimates contained in a report in the Lancet from the Global Burden of Metabolic Risk Factors of Chronic Diseases Collaborating Group. The paper appears in conjunction with the annual meeting of the American Diabetes Association.

Throughout the world diabetes prevalence has risen or, at best, stayed the same over the past 30 years, the authors report. Although most of the increase was due to population growth and an increased proportion of elderly people, 30% of the increase was due to an increase in risk factors such as obesity.

Using data from 2.7 million participants in various health surveys and epidemiological studies, they calculated for 2008 a mean FPG (fasting plasma glucose) of 5.50 mmol/L for men and 5.42 mmol/L for women. This represents a rise of 0.07 mmol/L in men and 0.09 mmol/L in women per decade.

Diabetes prevalence in 2008 was 9.8% in men and 9.2% in women, up from 8.3% and 7.5% in 1980. The highest levels and the biggest increase in FPG occurred in Oceania.

The authors write that “glycemia and diabetes are a rising global hazard.” In a Lancet press release, Majid Ezzati, an author of the report, said: “Diabetes is one of the biggest causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Our study has shown that diabetes is becoming more common almost everywhere in the world. This is in contrast to blood pressure and cholesterol, which have both fallen in many regions. Diabetes is much harder to prevent and treat than these other conditions.”

June 24th, 2011

FDA Recommends More-Conservative Dosing of ESAs

Larry Husten, PHD

The FDA today said that it was recommending more-conservative dosing of ESAs (erythropoiesis-stimulating agents) in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). The possible beneficial effects of the drugs to decrease the need for transfusions in CKD patients should be weighed against the increased risk for cardiovascular events, the FDA said. ESA therapy should be given at the lowest possible dose to reduce the need for transfusions. Currently available ESAs include epoetin alfa, marketed as Epogen (Amgen) and Procrit (J&J), and darbepoetin alfa, marketed as Aranesp (Amgen).

The FDA action follows last October’s advisory committee meeting, which itself followed the publication of the TREAT trial in the previous year. Here is the FDA summary of the label change:

The ESA labels now warn:

- In controlled trials with CKD patients, patients experienced greater risks for death, serious adverse cardiovascular reactions, and stroke when given ESAs to achieve a target hemoglobin level of greater than 11 g/dL.

- No trial has identified a hemoglobin target level, ESA dose, or dosing strategy that does not increase these risks.

The ESA labels now recommend:

- For patients with CKD, consider starting ESA treatment when the hemoglobin level is less than 10 g/dL. This advice does not define how far below 10 g/dL is appropriate for an individual to initiate. This advice also does not recommend that the goal is to achieve a hemoglobin level of 10 g/dL or a hemoglobin level above 10 g/dL. Individualize dosing and use the lowest dose of ESA sufficient to reduce the need for red blood cell transfusions. Adjust dosing as appropriate.

The drug label previously recommended that ESAs should be dosed to achieve and maintain hemoglobin levels within the target range of 10 to 12 g/dL in CKD patients. This target concept has been removed from the label.

The FDA said that a hemoglobin level above 11 g/dL raises the risk for serious adverse cardiovascular events and has never been shown to provide additional benefit. The FDA further noted that “no clinical trial to date has identified a hemoglobin target level, ESA dose, or dosing strategy that does not increase” the risk for cardiovascular events.

June 23rd, 2011

The Elusive 30-Minute “Door-In to Door-Out” Benchmark for Primary PCI Transfers

CardioExchange Editors, Staff

The editors at CardioExchange have again asked a panel of experts to respond to a clinically important study. This time it was a retrospective cohort study, published in JAMA, of door-in to door-out (DIDO) times for patients with ST-segment-elevation MI who had been admitted to one hospital and then were transferred to another center for primary PCI.

Few of the nearly 15,000 transferred patients had a DIDO time of 30 minutes or less, but that short transfer time was associated with shorter reperfusion delays and lower in-hospital mortality than was a DIDO time >30 minutes. (See the CardioExchange news story on the study.)

We put two questions to four experts, including the lead author of the study. Here are their responses:

How should front-line clinicians respond to the finding that a DIDO ≤30 minutes had clear time-to-reperfusion and outcome advantages but that very few transferred patients actually met that time threshold?

![]() Tracy Wang (lead study author, Duke): These results are surprising given the tremendous focus on reducing reperfusion delays for STEMI patients in recent years. What’s even more surprising is that a substantial proportion of STEMI patients intended for primary PCI have DIDO times >90 minutes, rendering the guideline-recommended overall door-to-balloon time of ≤90 minutes impossible. Some of this may perhaps be explained by the fact that sicker patients may need more stabilization before transfer, but it certainly doesn’t explain the large majority of transferred STEMI patients with prolonged DIDO times. The results underscore the need to prospectively establish STEMI systems of care that facilitate communication and minimize redundancy to expedite transfer between STEMI referral and receiving centers.

Tracy Wang (lead study author, Duke): These results are surprising given the tremendous focus on reducing reperfusion delays for STEMI patients in recent years. What’s even more surprising is that a substantial proportion of STEMI patients intended for primary PCI have DIDO times >90 minutes, rendering the guideline-recommended overall door-to-balloon time of ≤90 minutes impossible. Some of this may perhaps be explained by the fact that sicker patients may need more stabilization before transfer, but it certainly doesn’t explain the large majority of transferred STEMI patients with prolonged DIDO times. The results underscore the need to prospectively establish STEMI systems of care that facilitate communication and minimize redundancy to expedite transfer between STEMI referral and receiving centers.

Timothy Henry (U. Minnesota): This article illustrates the importance of the DIDO time as a key component of the total door-to-balloon time. Regional STEMI systems should focus on the components of this delay and implement changes to shorten it. Still, based on a wealth of data, the overall door-to-balloon time remains the factor critical in our decision regarding the choice of reperfusion. Data from our regional STEMI system, currently under review, indicates the specific reason for the delay may be as important as the length of the delay itself.

Timothy Henry (U. Minnesota): This article illustrates the importance of the DIDO time as a key component of the total door-to-balloon time. Regional STEMI systems should focus on the components of this delay and implement changes to shorten it. Still, based on a wealth of data, the overall door-to-balloon time remains the factor critical in our decision regarding the choice of reperfusion. Data from our regional STEMI system, currently under review, indicates the specific reason for the delay may be as important as the length of the delay itself.

![]() Ivan Rokos (UCLA): From my emergency medicine perspective, the slow DIDO times at STEMI referral facilities do not surprise me. I believe the cause is multifactorial, most commonly due to bad systems rather than bad EM doctors and nurses. Most important, current literature demonstrates that having a prearranged plan between referral and receiving hospitals is critical, but it is often lacking in the real world. Multiple other key steps affect DIDO at the referral facility, including door-to-ECG, ECG-to-diagnosis, diagnosis to acceptance by the receiving hospital (an EMTALA requirement), acceptance to activation of transport, activation to arrival of transport vehicle, and transport team arrival to departure.

Ivan Rokos (UCLA): From my emergency medicine perspective, the slow DIDO times at STEMI referral facilities do not surprise me. I believe the cause is multifactorial, most commonly due to bad systems rather than bad EM doctors and nurses. Most important, current literature demonstrates that having a prearranged plan between referral and receiving hospitals is critical, but it is often lacking in the real world. Multiple other key steps affect DIDO at the referral facility, including door-to-ECG, ECG-to-diagnosis, diagnosis to acceptance by the receiving hospital (an EMTALA requirement), acceptance to activation of transport, activation to arrival of transport vehicle, and transport team arrival to departure.

![]() Jeptha Curtis (Yale): Clinicians need to critically examine the outcomes achieved at their own institutions. At a national level, these findings are a clear signal (one of many) that these patients are falling between the cracks. We have made such amazing strides with door to balloon times among patients who arrive at a PCI capable facility, but we have made little if any real progress with this vulnerable population. After reviewing their outcomes (which are likely to be equally dismal), clinicians at both sending and receiving hospitals need to get engaged- creating working groups, maintaining communication between hospitals, and convincing leadership to make the capital and personnel investments needed to improve.

Jeptha Curtis (Yale): Clinicians need to critically examine the outcomes achieved at their own institutions. At a national level, these findings are a clear signal (one of many) that these patients are falling between the cracks. We have made such amazing strides with door to balloon times among patients who arrive at a PCI capable facility, but we have made little if any real progress with this vulnerable population. After reviewing their outcomes (which are likely to be equally dismal), clinicians at both sending and receiving hospitals need to get engaged- creating working groups, maintaining communication between hospitals, and convincing leadership to make the capital and personnel investments needed to improve.

If patients cannot be transferred out within 30 minutes, should those eligible for lytic therapy receive it?

Tracy Wang (lead study author):![]() Absolute contraindications to fibrinolysis were found to occur rarely in the transferred STEMI population. Therefore, if DIDO time is anticipated to exceed 30 minutes, fibrinolysis should be considered among eligible patients depending on symptoms and bleeding risk.

Absolute contraindications to fibrinolysis were found to occur rarely in the transferred STEMI population. Therefore, if DIDO time is anticipated to exceed 30 minutes, fibrinolysis should be considered among eligible patients depending on symptoms and bleeding risk.

Timothy Henry: See Dr. Henry’s comment above.

Timothy Henry: See Dr. Henry’s comment above.

![]() Ivan Rokos: It depends on the setting (urban/suburban vs. rural/remote) because transport time (related to geography, weather, road conditions) also affects overall reperfusion time. Literature supports a pharmaco-invasive strategy for long-distance transfers >60 miles. For shorter transfers, transfer-PCI should generally be the goal. In Los Angeles County, our published data support transfer via 9-1-1 providers, who arrive at the receiving hospital ED with the same urgency as at any other “prehospital scene.” I am an optimist and believe that we can improve interhospital transfer by creating systems and networks that are supported by quality-improvement registries and benchmarks. The DIDO ≤30 minutes metric will, I hope, have the same national impact on improving interhospital transfer as D2B had on primary PCI for patients who present directly (via paramedic or self-transport) to a receiving hospital.

Ivan Rokos: It depends on the setting (urban/suburban vs. rural/remote) because transport time (related to geography, weather, road conditions) also affects overall reperfusion time. Literature supports a pharmaco-invasive strategy for long-distance transfers >60 miles. For shorter transfers, transfer-PCI should generally be the goal. In Los Angeles County, our published data support transfer via 9-1-1 providers, who arrive at the receiving hospital ED with the same urgency as at any other “prehospital scene.” I am an optimist and believe that we can improve interhospital transfer by creating systems and networks that are supported by quality-improvement registries and benchmarks. The DIDO ≤30 minutes metric will, I hope, have the same national impact on improving interhospital transfer as D2B had on primary PCI for patients who present directly (via paramedic or self-transport) to a receiving hospital.

![]() Jeptha Curtis: The easy answer is that every patient is different and needs to be assessed on a case-by-case basis. Yes, there will be situations where lytics should be given, but the question is not at the level of the individual patient, but rather is a function of what the system can reliably achieve. The reality is that clinicians and hospitals do much better when they pick a strategy and stick with it. I suspect adding a lytic arm to the decision matrix would only confuse matters and increase delays. Instead, hospitals that commit to a transfer strategy need to focus their efforts on reducing delays. However, they need to be willing to revisit that decision if they cannot get at least half of their patients out the door within 30 minutes.

Jeptha Curtis: The easy answer is that every patient is different and needs to be assessed on a case-by-case basis. Yes, there will be situations where lytics should be given, but the question is not at the level of the individual patient, but rather is a function of what the system can reliably achieve. The reality is that clinicians and hospitals do much better when they pick a strategy and stick with it. I suspect adding a lytic arm to the decision matrix would only confuse matters and increase delays. Instead, hospitals that commit to a transfer strategy need to focus their efforts on reducing delays. However, they need to be willing to revisit that decision if they cannot get at least half of their patients out the door within 30 minutes.

How would you answer the two questions we put to our experts? And what do you think of their answers?