June 15th, 2017

Educating Patients About HPV Vaccination Can Feel Like Peddling Snake Oil

Elizabeth Donahue, RN, MSN, NP-C

Messaging and medicine have always gone hand in hand. A Google search for wellness products of yesteryear produces a vibrant collection of ads for lotions and potions. Cod liver oil, hair tonics, and other extracts (including opium!) were promised to keep you feeling healthy and looking great. And using medical professionals to bolster product claims has long been popular in marketing. Even big tobacco companies used physicians in their print ads, citing doctors’ preference for a certain brand of cigarettes, or proclaiming one type “more filtered” or “less irritating” than the next. How effective they must have been!

Of course, these advertisements came at a time when consumers had less access to information. Now patients can see a list of ingredients, read a statistical analysis of outcomes, and rely on FDA and CDC data. Rules around advertising and claims about medicines have changed drastically. So why, in 2017, does it sometimes feel like I am peddling snake oil?

I particularly feel like this when it comes to recommending the HPV vaccine. Attending a lecture last week, I was relieved to hear that other providers feel similarly. The talk was given by an expert in STD prevention and treatment. As the conversation around HPV turned to the vaccine, and we were reminded of indications, insurance coverage, and other practical pearls, one pediatric NP asked others to share techniques they found successful in convincing parents to vaccinate their children. To be clear, low HPV vaccine uptake isn’t a case of anti-vaxxers refusing the intervention as part of an overall philosophy; rather, HPV vaccine refusal is repeatedly found in practice among a staggering number of patients and families who do opt for other vaccines. In my internal medicine setting, I see adult women, previously unvaccinated and about to age out of coverage, continuing to decline the vaccine. They do so because they recall their mothers declining it on their behalf during a shared office visit 10 years earlier.

I particularly feel like this when it comes to recommending the HPV vaccine. Attending a lecture last week, I was relieved to hear that other providers feel similarly. The talk was given by an expert in STD prevention and treatment. As the conversation around HPV turned to the vaccine, and we were reminded of indications, insurance coverage, and other practical pearls, one pediatric NP asked others to share techniques they found successful in convincing parents to vaccinate their children. To be clear, low HPV vaccine uptake isn’t a case of anti-vaxxers refusing the intervention as part of an overall philosophy; rather, HPV vaccine refusal is repeatedly found in practice among a staggering number of patients and families who do opt for other vaccines. In my internal medicine setting, I see adult women, previously unvaccinated and about to age out of coverage, continuing to decline the vaccine. They do so because they recall their mothers declining it on their behalf during a shared office visit 10 years earlier.

But here’s the thing about the HPV vaccine — it really DOES do what it is supposed to. And what it is designed to do is a pretty big deal — preventing a virus that we know causes cancers. We have no other tool in our arsenal that actively prevents cancer in this way. We can reduce our risk through behavior avoidance and early screening for several of the most prevalent cancers, but this vaccine prevents the development of disease.

One commonly cited barrier to vaccine uptake is stigma about the sexual nature of HPV. HPV vaccines prevent disease transmitted through sexual contact. Anecdotally and from research findings, we often hear that parents resist because they are uncomfortable talking about the sexual health of their young children, or because they reason that it will lead to increased or earlier sexual activity (see this JAMA commentary). The data I have seen support the vaccine on those counts; in this cross-sectional study and this review, for instance, authors found no evidence of changes in sexual behaviors in vaccinated groups when compared with their non-vaccinated peers.

As for possible solutions, some experts suggest desexualizing the conversation – pointing to non-sexual routes of HPV transmission and non-genital cancers. Another possibility might be to consider nontraditional settings for vaccine education and administration. For instance, school-based anti-HPV programs in Australia include non-compulsory vaccine days that have resulted in coverage of more than 70% of the targeted adolescent female population and are already showing decreases in infections and cervical abnormalities. An extension of the program to adolescent males has also demonstrated success.

As for possible solutions, some experts suggest desexualizing the conversation – pointing to non-sexual routes of HPV transmission and non-genital cancers. Another possibility might be to consider nontraditional settings for vaccine education and administration. For instance, school-based anti-HPV programs in Australia include non-compulsory vaccine days that have resulted in coverage of more than 70% of the targeted adolescent female population and are already showing decreases in infections and cervical abnormalities. An extension of the program to adolescent males has also demonstrated success.

Since attending that lecture, I have come to see the conundrum more clearly. I think that I had taken on my patients’ reticence to the vaccine by osmosis, which was negatively affecting my communication. I was almost apologetic when bringing up the vaccine recommendation and as a result was presenting my customers with a “soft” sales pitch. I would start off with something like, “I understand your concerns, but…” And when they would decline, I would leave the room wondering why I hadn’t closed the deal, while my rational brain was still screaming about the power of prevention, the data, the efficacy! I now realize that negative patient views of the HPV vaccine had subtly affected my approach – made me timid in my discussion and gave validation to their concerns, weakening my argument from the start. Now I am more adamant, I go in for the close right away: Here are the studies, the vaccine works, now let’s get down to business.

If you’ve found a successful approach to convincing hesitant patients or parents of the HPV vaccine’s importance, I’d love to hear about it. Please share it in the comments below.

June 9th, 2017

How Giving Friends and Family Medical Advice Made Me Sick

Emily F. Moore, RN, MSN, CPNP-PC, CCRN

Emily F. Moore, RN, MSN, CPNP-PC, CCRN practices pediatric cardiovascular care across the Pacific Northwest.

The other night, my sister called me asking if she should take my niece to the emergency department. She had been complaining of abdominal pain with on-and-off vomiting and diarrhea for a couple days. According to my sister, she had gotten to the point where the pain was unbearable. I quickly ran through my niece’s symptoms, asked a few questions, and developed a differential of what I thought it might be. I was quite certain she had an appendicitis, but thought perhaps I was overreacting given that this was my niece, not my average patient. Come to find out, she not only had an appendicitis, but her appendix had ruptured and she was quite ill.

Since I graduated from nursing school, it is not uncommon for my family or friends to call seeking medical advice. Initially, I didn’t think anything of it. I was flattered that my (large) family trusted me with their queries. However, as my practice began to focus more and more on pediatric cardiac surgery and less on pediatric primary care, I began to recognize how much I did not know regarding noncardiac body systems.

This left me not only constantly questioning the advice I had given, but also worrying about the legalities related to the situation. Granted, I was not actually prescribing for or treating my family, but they were querying me frequently over fevers, rashes, ear pain, stomachaches and the like. With each query, I would second-guess myself and perseverate over advice given. What if I had dismissed that rash as contact dermatitis and it was actually infectious, an allergic sensitivity, or something more bizarre? I couldn’t help but think that if the advice I’d given over the phone was wrong, I would land in court defending myself. This was an irrational fear, as I didn’t actually think that my family or friends would sue me. Nonetheless, it caused me a great deal of stress.

This left me not only constantly questioning the advice I had given, but also worrying about the legalities related to the situation. Granted, I was not actually prescribing for or treating my family, but they were querying me frequently over fevers, rashes, ear pain, stomachaches and the like. With each query, I would second-guess myself and perseverate over advice given. What if I had dismissed that rash as contact dermatitis and it was actually infectious, an allergic sensitivity, or something more bizarre? I couldn’t help but think that if the advice I’d given over the phone was wrong, I would land in court defending myself. This was an irrational fear, as I didn’t actually think that my family or friends would sue me. Nonetheless, it caused me a great deal of stress.

Another unpleasant side effect of trying to help was the pushback I received. The level of questioning I got in response to my advice was almost insulting at times. In my head, I told these callers, “If you trusted me enough to call me with your ailment, why aren’t you trusting my opinion?” “If Dr. Google says otherwise and you already researched this, don’t ask me.” “If you generally want my opinion, I am happy to give it, but please, I can’t stress it enough, do not rebut me with the latest entry on Wikipedia.” Of course, I never I actually said any of this.

Things came to a head when I was surrounded by a lot of severe illness in my family. Naturally one to externalize my stress, I began to notice various physical symptoms and poor sleep setting in. I knew I didn’t need to see my primary care provider, but I wanted to address my stress level. So, taking advantage of my employer benefits, I consulted with a naturopath, who recognized my infirmities as anxiety over giving my family and friends the wrong medical advice. I love my family, and I certainly love helping. However, the thought of providing misleading advice was almost crippling. I found myself thinking and rethinking the most simple of complaints.

After seeing my naturopath, I decided to cut the cord on providing medical advice to non-patients. My clinician gave me strict instructions to not respond to texts after 7 PM. As those hooked on communication devices (all of us, it seems?) can imagine, this was like having an itch I couldn’t scratch. The compulsion to check my phone haunted me. Nevertheless, I stuck to it, and I also made a plan to set firm boundaries with those calling with medical questions. I started telling people things like, “My specialty is pediatric cardiology and cardiac surgery. I am sorry your finger is swollen, but you’ll have to see your provider if it is bothering you” and “I can help change a dressing, but no, I will not buddy tape your toe and diagnose it as broken. For that, you need to see a provider.”

After seeing my naturopath, I decided to cut the cord on providing medical advice to non-patients. My clinician gave me strict instructions to not respond to texts after 7 PM. As those hooked on communication devices (all of us, it seems?) can imagine, this was like having an itch I couldn’t scratch. The compulsion to check my phone haunted me. Nevertheless, I stuck to it, and I also made a plan to set firm boundaries with those calling with medical questions. I started telling people things like, “My specialty is pediatric cardiology and cardiac surgery. I am sorry your finger is swollen, but you’ll have to see your provider if it is bothering you” and “I can help change a dressing, but no, I will not buddy tape your toe and diagnose it as broken. For that, you need to see a provider.”

Slowly but surely, the healthcare queries stopped. I do still get calls; the case of my niece is a perfect example. I would be upset had my sister not called in that situation. Overall though, the number of queries has lessened and, most importantly, I can sleep at night again.

May 31st, 2017

Curing the Toxic Culture: First, Honor Thy Patient

Harrison Reed, PA-C

In March I wrote a blog post for In Practice that detailed some of the devastating effects of a toxic workplace culture. It’s worth a read, but the main points are easily summarized: abusive environments in medicine affect nearly every aspect of professional performance and hurt both businesses and patients. They lead to lower productivity, higher absenteeism and turnover of employees, and decreased patient satisfaction. At least one large study has even linked poor workplace culture to higher patient mortality.

But I pulled a nasty trick in that last entry. I showed you a problem — and hopefully elicited some level of concern — and then dropped the mic without offering a solution. There’s a good reason for that: I don’t have one.

If there were one easy answer to fix healthcare culture, I would bottle it and travel the country selling it out of the trunk of my car. But in reality the cure for the culture is likely multi-faceted, a million small drops in an enormous bucket. Facing an insurmountable task, however, is no reason to procrastinate. There are some things we can do right now to start filling the bucket.

Step #1 starts with the most obvious but often obfuscated part of the equation: our patients. We can’t expect to treat each other better if we don’t first respect our common mission. The following ideas may prime the pump for a better patient care environment.

The Right Address

A name is often the first thing you learn about a patient when you pick up a chart or knock on an exam room door. How we address patients, to their faces or among ourselves, sets the tone for the entire relationship.

“When did our patients stop being ladies and gentlemen?” I remember one of my favorite physicians asking a room of students during my training. A respectful title might be the only way someone maintains dignity after he dons a faded hospital gown. Default to “sir” or “ma’am” or the respectful cultural analog. If patients later want you to call them by their first name or their nickname or their Twitter handle, leave that to their discretion.

Even with the best of intentions, few things are as condescending as calling an adult stranger “Honey,” “Sweetie,” or “Dear.” Early in my career I made this mistake, thinking it would comfort my patient as her blood pressure plummeted and she neared cardiac arrest. With her last few seconds of consciousness she turned to me and said, “That’s ‘ma’am’ to you.”

She was right.

They’re Listening

Regardless of their clinical condition, assume your patients are listening to you. They probably are. Exam room curtains aren’t soundproof and endotracheal tubes don’t block tympanic membranes. Even sedated patients are often aware of their surroundings. And families walking through the halls definitely are.

Speak to — and about — patients as if they can hear you at all times. Sure, it might look silly when you update an unresponsive person on his care plan or talk a sedated patient through a procedure. But some of you have probably discussed your dating woes with your pet cat, so you can certainly manage this.

Talk Nerdy

Conversations with patients and families represent a minefield rife with opportunities for miscommunication. Clinicians who spit out too much medical jargon can leave laypeople dazed and confused. Conversely, dumbing down a subject below your patient’s understanding can add insult to injury.

While we are often taught to limit medical terminology in discussions with patients, I like to use it and then quickly define or explain it. This covers both of the above scenarios, and the quick education can inoculate your patient against the next clinician who comes in flinging technical terms.

Incremental changes can, over time, increase the sense of professional pride in your workplace. The kindness you show your patients is much more likely to translate to respect among your colleagues. It’s a small but important step toward curing the toxic culture.

May 18th, 2017

Changing Health Care — Reflections from Across the Pond

Megan Tetlow, PA-C

Megan Tetlow, PA-C, is from Fort Myers, Florida, now working in Sheffield, England, as part of the National Physician Associate Expansion Program. She practices in gynecologic oncology and is a guest blogger for In Practice.

I’m an American physician assistant living and working for the government-funded National Health Service (NHS) in the U.K. I also write for this blog about the differences between the U.S. and U.K. health systems. I have thus far been moderately successful at avoiding political discussions in the public sphere. But the recent passage of the American Health Care Act by the U.S. House of Representatives has me changing my tune. Let me explain why.

Scrolling through social media, I saw a GoFundMe page from a family struggling to cope financially in light of an unexpected diagnosis — a heart-wrenching story of a young mom diagnosed with cancer while pregnant. Now she (and her spouse) face the financial and emotional complications of undergoing primary chemotherapy and radiation while caring for a newborn and two other young children. Any parent can tell you how difficult it is to care for a newborn, much less doing so while undergoing cancer treatments … and taking care of other children … and not taking too much time off work lest you lose your job and, with it, your employer-sponsored health insurance and main source of paying medical bills. The most disturbing part of this story is how shockingly prevalent it appeared to be. I realized we live in a world where a working American family must rely on the charitable donations of strangers to have a chance of survival.

When British health care providers talk to me about health care in the U.S., their great fear is of patients needing care that they won’t receive because they can’t afford it. I explain private insurance and Medicaid and how many practices treat patients regardless of their ability to pay. But the truth is, there are millions of families who make too much to qualify for Medicaid but not enough to afford top-tier private insurance. And even if you have good insurance, you’ll likely have to pay a large amount out of pocket in addition to your sizable monthly premiums, should you ever actually need to use it. For instance, my mother broke her shoulder last year, and despite good employer-sponsored private insurance, she paid $8,000 out of pocket for the required surgery.

When British health care providers talk to me about health care in the U.S., their great fear is of patients needing care that they won’t receive because they can’t afford it. I explain private insurance and Medicaid and how many practices treat patients regardless of their ability to pay. But the truth is, there are millions of families who make too much to qualify for Medicaid but not enough to afford top-tier private insurance. And even if you have good insurance, you’ll likely have to pay a large amount out of pocket in addition to your sizable monthly premiums, should you ever actually need to use it. For instance, my mother broke her shoulder last year, and despite good employer-sponsored private insurance, she paid $8,000 out of pocket for the required surgery.

Unfortunately, these problems will only increase if the American Health Care Act is passed by the Senate. For example, the home state of the patient described above could choose to make cancer a pre-existing condition. If that happened, she could expect her insurance premiums to skyrocket. Even more troubling, under this new act, the patient’s pregnancy itself could potentially be classified as a pre-existing condition.

It has always bothered me that in the U.S. health system, one  diagnosis or hospitalization can equate to economic ruin for a patient. However, it was not until I became a health care provider and resident in another country and in another health culture that I acquired a different perspective. I no longer believe that these situations are unfortunate—rather, they are inevitable. But they should be avoidable, and and I find them no longer tolerable.

diagnosis or hospitalization can equate to economic ruin for a patient. However, it was not until I became a health care provider and resident in another country and in another health culture that I acquired a different perspective. I no longer believe that these situations are unfortunate—rather, they are inevitable. But they should be avoidable, and and I find them no longer tolerable.

I also find it intolerable that a health care bill opposed by the American Medical Association, American Academy of Family Physicians, American Nursing Association, and other professional medical organizations could be presented to Congress as a serious plan, let alone passed by the House.

I had always thought that as a health care provider, it was my duty to do the best I could for my patients, within the restraints of the system. I worked hard to help patients who couldn’t afford treatment to get linked up with charity groups or patient assistance. I filled out Medicaid applications and sent appeal letters to insurance companies. But I didn’t fight to change the system. Now, I believe that as health care providers, we must go a step further and become patient advocates, fighting bad health care policies as vigilantly as we fight disease. Our patients deserve it.

May 11th, 2017

Leaving Against Medical Advice (AMA): A Clinician’s Dilemma

Alexandra Godfrey, BSc PT, MS PA-C

“You’ll have to sign out against medical advice (AMA) . Your blood pressure is high.” The ER physician stood in the doorway of my room.

“What difference would it make now?” I asked.

The doctor fiddled with the cuffs of his white coat, then glanced at his cell phone.

I picked up my car keys.

“High blood pressure is dangerous,” he added.

I looked down at the floor, watching puddles form around my feet as the snow melted on my UGGs. A cold wind blew snow against the window, causing the blinds to rattle.

“I don’t know the cause of death,” I said.

The doctor tapped his foot on the floor; “You could have a stroke. And your insurance might not cover this visit, if you leave AMA.”

I leaned forward in my chair, holding my head in my hands. It was then that I saw the photograph tucked in the top of my purse. Perhaps this would help?

I reached into my purse and offered the picture to the doc – that grainy ultrasound image of my son.

“Do you want to see his picture?” The doctor shook his head. I crumpled in my seat. Tears gathered.

“High blood pressure might damage your kidneys or your heart,” he said, crossing his arms over his chest.

Damage my heart?

I bit down on my bottom lip, then formed my hands into a temple. My obstetrician had insisted I come to the ER. I hadn’t wanted to come. The experience had been awful from the beginning.

I looked at the doctor through the arches of my fingers.

“Do you own a dictionary.” I asked.

“Yes – why?”

“You should look up the word empathy,” I replied in a quiet voice.

I got up then and walked out. I did not look back. Not once.

I had never left a hospital AMA before. And I have not left AMA since. Even now, years on, I know I made the right choice. It changed everything.

The AMA Dilemma

Certainly, patients discharged against medical advice are both a concern and a challenge for healthcare providers due to the increased risk of both litigation and adverse medical events. Furthermore, these patients are more likely to be readmitted for the same or a related condition. Additionally, they frequently suffer from serious underlying pathology.

What does leaving against medical advice (AMA) mean?

When a patient leaves AMA, the patient is leaving before their treating physician recommends discharge or despite medical advice to the contrary.

This definition implies the patient received and understood the medical advice given. In practice, the term AMA is often used regardless of whether medical advice was given or not. Additionally, patients are frequently required to sign an AMA form. Unfortunately, these attestation forms are often confusing, coercive, and written in language beyond the reading level of the patient.

This creates two important questions:

- If a patient does not have sufficient information or understanding to make informed decisions, are they in fact leaving against medical advice?

- Shouldn’t health literacy be a consideration in AMA discharges?

Who leaves AMA?

Identifying those patients most at risk for leaving AMA is important if we are to design interventions to prevent it. Variables include:

- Alcohol or substance abuse

- Male sex

- HIV/AIDS

- Low socioeconomic status

- History of leaving AMA

- Black race

- Psychiatric disorders

- Absence of health insurance

- Homeless

AMA Healthcare Disparities

Certainly, the choice to leave a medical facility lies with the competent patient, but the choice to designate the discharge as AMA lies with the medical provider. Despite this, there is a lack of data about providers who discharge patients AMA. To fully understand AMA predictors, we need to know more about clinicians.

It is well known that clinician attitudes vary based on patient characteristics. Such variability may shape the quality of care given. Stigma may result in lower quality care resulting in poorer outcomes. Furthermore, if you consider the groups most at risk for AMA discharge, there’s clear intersectionality between them. For instance, a black sexual minority male is more likely to be homeless, less likely to have insurance, and at higher risk of depression or other mental illness. Consequently, a disproportionate number of patients leaving AMA come from stigmatized or marginalized minority groups.

Why do patients leave AMA?

Recognition of the reasons patients leave can help us negotiate these encounters. They may include:

- Personal and financial obligations

- Breakdown of communication between the patient and medical staff

- Dissatisfaction with care

- Lack of trust in the healthcare provider

- Not understanding the need for further testing or treatment

Medico-legal Considerations

Above all, providers need to be aware that the simple signing of an AMA form does not confer absolute medico-legal protection. Furthermore, not giving discharge instructions, follow-up or medications could be construed as coercion, negligence or unwillingness to consider alternative options for the patient. Moreover, advising a patient that their insurance will not cover their visit if they leave AMA is not only incorrect but could also be considered coercion.

This article provides an excellent review of medico-legal standards.

In Conclusion

For me, leaving the ER AMA gave me precious time alone with my son. Moreover, it removed me from a hostile and unpleasant situation. I returned to the hospital the next day to deliver my son. He had died suddenly in the second trimester. No amount of ER medicine would have changed that outcome. My experience that night precipitated my return to education and pursuit of a career as an emergency medicine PA.

Certainly, the onus is on all providers to carefully examine the role that their bias, language, and behavior might play in triggering an AMA discharge. Furthermore, patients must understand the medical advice given and the potential sequelae of their decisions if we are to document AMA. Providers should take time to explore their patient’s thinking and engage them in shared decision making. Repairing the patient-clinician alliance may help facilitate communication and rebuild trust. And of course, you don’t get told to read the dictionary…

May 5th, 2017

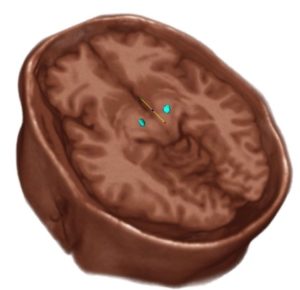

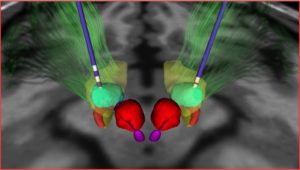

Deep Brain Stimulation Targeting in Neurosurgery, Part III of III

Bianca Belcher, MPH, PA-C

This is the final part of a three-part series on deep brain stimulation (DBS) targeting designed for providers who lack an intimate level of knowledge and/or experience with this subject matter. In Part I, I discussed the ventralis intermedius (Vim) target as well as an overview of DBS, equipment, and programming, and Part II covered the globus pallidus internus (GPi). This final part is a review of the subthalamic nucleus (STN), the default target in some institutions. There is more scientific literature about the STN than about other targets [1], but this is changing.

Subthalamic Nucleus (STN)

Where is it located?

The STN is located just below the thalamus at the posterior limb of the internal capsule, medial to cranial nerve III, and inferior to the substantia nigra.

- Parkinson’s Disease (PD)

- Stimulation of the STN treats the cardinal motor symptoms of PD more effectively than GPi or Vim.

- Patients with severe “ON/OFF” fluctuations tend to do better with STN lead placement.

- STN placement provides the best chance of achieving post surgical medication reduction.

- The STN, a smaller target than the GPi, often requires lower voltage to achieve symptom relief, leading to less frequent battery changes. If a patient is young and may require several battery changes over their lifetime, this may be a secondary consideration after optimal symptom relief. Of note, there is a rechargeable battery on the market that may negate this consideration in some patients.

Cautions:

- If dystonia is present, stronger consideration is usually given to GPi placement over STN.

- Psychiatric comorbidities in patients can be exacerbated with stimulation around the STN. Our patients undergo neuropsychological testing prior to target selection to mitigate this risk.

Adverse side effects of stimulation based on location of electrode in relation to optimal placement [2]:

Too lateral – With stimulation of the motor and frontal eye fibers of the internal capsule, the patient would experience muscle contractions, dysarthria, and contralateral gaze deviation.

Too medial – Diplopia, eye deviation, sweating, nausea, depression, and personality changes can all be a consequence of stimulating medial structures such as the nerve roots of CNIII, the red nucleus, or the ventromedial portion of the STN.

Too posterior – With stimulation of the medial lemniscus, the patient will experience paresthesias.

Too anterior – The patient will experience muscle contractions and autonomic symptoms such as panicky feelings or sweating due to stimulation of the hypothalamus or motor fibers of the internal capsule.

Too superior – No effect on tremor

Too deep – Mood changes and muscle contractions due to stimulation of the substantia nigra or the internal capsule

References

- Deep Brain Stimulation Management. William J. Marks, Jr. Cambridge University Press 2010

- DBS Anatomy & Side Effects. A Presentation by Kirk Finnis, PhD. Medtronic.

April 27th, 2017

Getting Worked Up Over Kids’ Fevers

Emily F. Moore, RN, MSN, CPNP-PC, CCRN

Emily F. Moore, RN, MSN, CPNP-PC, CCRN practices pediatric cardiovascular care across the Pacific Northwest.

Few things worry a mother more than a baby with a fever. With my own girls, I am naturally uneasy and do not like when they have fevers, even though as a health care provider I know that fevers are natural. But it wasn’t until my three-year-old started having chronic fevers that I realized how unsettling it could be.

Her fevers first started shortly after she turned 6 months and coincidentally started daycare. I thought it was a sign that her body was building her immune system. Her fevers ranged anywhere from 101 to 105 degrees and occurred randomly every few weeks to months. Sometimes she was miserable, at other times she was fine and played right through them. Through it all she thrived. I was never once worried about her development.

After her subsequent diagnoses of chronic ear infections, pertussis, pneumonia, periorbital cellulitis, reactive airway disease, and influenza, we were referred to immunology for an extensive workup. I remember sitting there thinking, as a provider, that she was fine. She had followed a normal growth curve, was meeting developmental milestones, and was ahead of the curve academically. But as a mother, I couldn’t help but worry — what would I do if anything came back positive? Our provider’s initial clinical impression was that my daughter likely had cyclic fever disorder and there would be nothing we could do. In order to make this diagnosis, we had to rule out T and B cell dysfunction. So we were sent to have lab work done.

After her subsequent diagnoses of chronic ear infections, pertussis, pneumonia, periorbital cellulitis, reactive airway disease, and influenza, we were referred to immunology for an extensive workup. I remember sitting there thinking, as a provider, that she was fine. She had followed a normal growth curve, was meeting developmental milestones, and was ahead of the curve academically. But as a mother, I couldn’t help but worry — what would I do if anything came back positive? Our provider’s initial clinical impression was that my daughter likely had cyclic fever disorder and there would be nothing we could do. In order to make this diagnosis, we had to rule out T and B cell dysfunction. So we were sent to have lab work done.

Had I known the extent of the lab work needed, I may have asked more questions to prepare myself and my daughter on what to expect. Instead, I ended up holding my daughter while she screamed, “They are bleeding me, Mama!” Everything came back normal, and we settled with the diagnosis of fever syndrome. Our provider wanted to send us to rheumatology and run more labs, and she also discussed the possibility of a tonsillectomy. At that point, I elected not to work her up any further and only treat symptoms as they presented. I knew there was not much more we could do, and the thought of continued testing sounded traumatizing, for both of us.

Fevers are one of the most common clinical symptoms managed by pediatricians and health care providers in general. Parents are often concerned with the need to maintain a normal temperature. Yet, the use of antipyretics is not always beneficial. We should be teaching our parents to treat symptoms, not numbers. When providing counseling, we should emphasize the child’s comfort and signs of serious illness rather than normothermia. Of course, we should teach parents that it’s important to seek care when fever persists after 3 days in infants and children, for any fever in a baby who is 3 months old or less, or if fever is over 104 degrees. But we also need them to trust their instincts. If a child looks unwell in the face of fever and doesn’t seem to be improving as one would expect, it is okay to call the pediatrician for help.

Fevers are one of the most common clinical symptoms managed by pediatricians and health care providers in general. Parents are often concerned with the need to maintain a normal temperature. Yet, the use of antipyretics is not always beneficial. We should be teaching our parents to treat symptoms, not numbers. When providing counseling, we should emphasize the child’s comfort and signs of serious illness rather than normothermia. Of course, we should teach parents that it’s important to seek care when fever persists after 3 days in infants and children, for any fever in a baby who is 3 months old or less, or if fever is over 104 degrees. But we also need them to trust their instincts. If a child looks unwell in the face of fever and doesn’t seem to be improving as one would expect, it is okay to call the pediatrician for help.

In regard to my daughter, she continues to blossom despite these recurrent fevers and infections. I have learned to take her fevers as one of many symptoms that develop when responding to infection. I certainly use medications like Tylenol when she is especially feverish, refusing to eat, punked out, and exhausted. This works, and she often quickly bounces back, regaining energy and improving her fluid intake and appetite. But I certainly don’t treat every fever, and I don’t recommend to my patients’ parents that they run for the medicine cabinet whenever they feel a warm forehead.

April 14th, 2017

Is There an NP on Board?

Elizabeth Donahue, RN, MSN, NP-C

It was a moment I’d anticipated for nearly 7 years — not with excitement, but with dread. Two weeks ago, I boarded a plane, having won the lottery known as the standby list. Due to heavy wind, all flights were departing from a single runway and because of delays, the airline had thrown in a complimentary cocktail. Things seemed to be going smoothly. Then just before starting our descent, a female passenger fainted onto the floor of the aisle next to my seat.

As I jumped up to help, I had a few thoughts:

- Thank God I only had one drink.

- I’m on vacation – but here’s one more patient literally dropped at my feet.

- Oh shoot – it’s actually happening.

You see, I’ve had anxiety about just such a situation since 2006. One time, I was flying to a meeting in California with three outstanding physician colleagues when the pilot asked for medical assistance. They handled the emergency beautifully, of course. Since then, I’ve thought about my lack of emergency experience whenever I’m on a plane. Multiple times I’ve joked that if a fellow passenger is in need of diabetes education or has strep throat or any number of primary care complaints, I’ve got this under control. But a medical emergency at 30,000 feet? What could I contribute?

Turns out, more than I thought. First of all, my training of nearly a decade allowed me to remain calm and focused. My daily work and my international aid experience reinforced an ability to complete an assessment using the tools I have at my disposal, thereby garnering a lot of information. And the ability to quickly develop a differential diagnosis came in more handy than I ever thought it would – thanks to my teachers and preceptors! As medical emergencies go, this one was mild. It seemed a case of vasovagal syncope – the patient didn’t have a head injury and was awake within seconds. She had a pulse, a normal neuro exam (thanks to the makers of the iPhone for that flashlight), and appeared a reliable historian who knew her medical history. Not to mention, we were close to our destination and on the ground in no time.

After the adrenaline slowed, I started unpacking the experience and reflected on how it felt. The flight attendants were great teammates – getting what I needed almost as soon as I asked. And the patient behaved the same way – responsive and grateful, without questioning my decisions or experience. I was in charge completely even though I was doubting myself. Why did this feel different from my daily work?

After the adrenaline slowed, I started unpacking the experience and reflected on how it felt. The flight attendants were great teammates – getting what I needed almost as soon as I asked. And the patient behaved the same way – responsive and grateful, without questioning my decisions or experience. I was in charge completely even though I was doubting myself. Why did this feel different from my daily work?

As a nurse practitioner, I’m used to defending my practice. I explain my role to patients, which I am happy to do – some don’t know what an NP does; some have never seen one before. I consider it an opportunity for education and discussion. I’ve also had patients question an evidence-based plan of care, wondering if my credentials equipped me to make the decision alone or if we needed to check in with a physician. Again, I don’t take this personally – I can see it as a place to better understand a patient’s concern or a chance to explain something more clearly. Other conversations are less pleasant; one patient’s family member recently accused me of wearing my badge flipped over to hide my status as a non-physician and asked for a doctor, though he had confirmed the appointment with an NP earlier that day. This, also, I can understand – patients simply want what is best or most comfortable, while they may feel unwell, stressed or scared. I can empathize and do my best to reassure them. I can also involve physician colleagues for reassurance and often do.

What has been more troubling to me is observing similar reactions from healthcare colleagues. Last year, a physician testified before the Massachusetts legislature that nurse practitioners “aren’t even trained to diagnose ear infections” – an allegation without basis in reality. Physicians within my hospital have asked to speak to a doctor in my office about a patient of mine – either not understanding that an NP could be the primary care provider, or that speaking to the provider who had actually delivered the care would be best for the patient (even if they didn’t have the “better” credentials). Several physicians have weighed in on blogs here at In Practice with sharp comments like, and forgive me for paraphrasing, “PAs don’t practice medicine” or “everyone wants to be a doctor with only 6 years of college.” In fact, we are practicing and my graduate degree (much like yours) is simply not equal to a few extra years of “college.”

I have worked collegially with physicians across my career. I am educated on my role and scope of practice, and I don’t hope to practice outside of my license. Nor do I have any illusions that I can know everything or will never need help. I am aware of my strengths and I work collaboratively with physicians and other colleagues as needed. I have often seen that this is a two-way street. An intelligent and well-respected physician colleague often asks me questions about women’s health, in which she had minimal training and I have more experience as a family medicine practitioner.

I have worked collegially with physicians across my career. I am educated on my role and scope of practice, and I don’t hope to practice outside of my license. Nor do I have any illusions that I can know everything or will never need help. I am aware of my strengths and I work collaboratively with physicians and other colleagues as needed. I have often seen that this is a two-way street. An intelligent and well-respected physician colleague often asks me questions about women’s health, in which she had minimal training and I have more experience as a family medicine practitioner.

I wonder; if there had been a doctor on that plane, would my skills or contribution have been questioned? What if that doctor was one with minimal experience in the chief complaint – say, a psychiatrist or an orthopedist? Would there have been a recognition that although I have different letters after my name, I may have been better suited to care for this patient? If there had been an EMT, an ICU nurse, or an ER doctor on the plane, I would have stepped aside without ego, in the best interest of the patient. To that end, I hope we as providers can begin to treat all situations as opportunities to work together as colleagues without unfairly judging each other’s credentials.

April 10th, 2017

Pulmonary Embolus: Evaluating the Five Ps of PE

Alexandra Godfrey, BSc PT, MS PA-C

Years ago, my physician father said to me; “If something does not make sense, if you struggle to determine the pathology, consider pulmonary embolus (PE).”

More recently, an ER physician colleague offered me the following advice: “If you think about PE, test for it.”

Of course, an astute clinician places both pieces of wisdom into context. I am not going to look for PE in patients presenting with ambiguous abdominal pain nor am I going to order d-dimers on all patients with a hint of PE. I also accept that tucked in the fables and parables of medicine are certain truths that deserve my attention. The first piece of advice speaks to the cryptic and non-specific presentation of pulmonary embolus and the second refers to the importance of clinical suspicion or gestalt.

The mortality, morbidity, and prevalence of PE combined with its enigmatic presentation can cause trepidation and uncertainty in providers, sometimes triggering haphazard or inappropriate testing. Such testing may result in poor outcomes for patients (and providers). Moreover, the confusion is compounded by conflicting opinion and divergent practice: some providers never order a d-dimer, some order one on every low-risk patient, some start with CTA, etc. If I ask three clinicians about their work-ups, I will likely get three quite different answers. Furthermore, anecdotes are powerful; we all have stories about the most unlikely presentation of PE. Consequently, PE evaluation can be as murky and off-putting as my grandmother’s pea soup (sorry, grandma). Nonetheless, even though PE is a pernicious, petulant and peculiar pathology, we can find clarity if we carefully consider the five Ps of PE evaluation. What is more – you can count them on the phalanges of one hand.

P1. Patient Presentation

Step one: look at your patient. Prior to any testing, perform a thorough history and physical. Patients with PE present in a variety of ways and symptoms can be subtle. Symptoms of PE include: dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, cough, syncope, hemoptysis, tachycardia, fever, leg swelling. Dyspnea and chest pain are the most common symptoms of PE; however, neither is sufficiently sensitive or specific to rule pulmonary emboli in or out.

P2. Pre-test Probability

Step two: determine pre-test probability. You can use either your gestalt or validated clinical prediction rules to further stratify risk in your patient. My preference is to use a combination of the two, as my years in medicine have taught me two facts: firstly, my judgement is fallible, and secondly, some patients do not fit the rules. Knowing in medicine is never a simple algorithm or a score; it is a shared multidimensional process that transcends these.

P3. Prediction Rules

Step three: prediction rules. Well validated clinical prediction tools include the revised Geneva (rGeneva) and the two-step Wells’ scores.1 The rGeneva score is entirely objective. Patients are stratified in low, intermediate and high risk. The two-step Wells’ score divides patients into PE unlikely (≤4) and PE likely (>4). The criticism of the Wells’ score is that it incorporates clinical gestalt by giving 3 points for suspicion for PE. Both scores guide subsequent testing. A patient who is <50 years old and is considered low risk by gestalt or prediction tool can be further ruled out by using the Pulmonary Embolism Rule Out Criteria (PERC).

Undoubtedly, given the variability in use and inconsistent knowledge of these rules, serious consideration should be given to incorporating clinical decision tools (as computer support aids) in electronic charting, especially for providers who are inexperienced or risk-averse, or who infrequently stratify PE risk. These aids do not usurp gestalt but rather enhance it.

Step four: the d-dimer. Patients who don’t meet PERC should be further stratified by the plasma d-dimer, a fibrin degradation product that when present indicates the initiation of procoagulant and fibrinolytic pathways. D-dimers may rule out PE in low-risk and even moderate-risk patients, depending on the assay used. Remember, they are sensitive but not specific. Moreover, do not order d-dimers on high-risk patients as the increased incidence of disease in these patients creates spectrum bias (if you change the patient case mix, you change the performance of a test).

Different assays are available and have different cutoffs and units. A common and sensitive d-dimer assay is the ELISA. Another sensitive assay is the immunoturbidimetric. Both are quantitative. One of my practice sites uses the former and the other uses the latter. If you plan to age adjust the d-dimer you must know the following i) the type of assay, ii) the reporting unit, and iii) the cutoff. If you don’t know these things, you could make critical errors.

The greatest use of the d-dimer stems from its high negative predictive value. Thus the d-dimer is for patients who are “PE unlikely” by Wells (≤4) or gestalt but are not ruled out by PERC. The ELISA d-dimer assay can also be used in conjunction with clinical prediction tools to rule out patients with intermediate risk.

Age adjusting the d-dimer to further stratify risk and reduce unnecessary imaging while maintaining sensitivity is a hot topic. The American College of Physicians recommends using age-adjusted d-dimer thresholds (age x 10 ng/ml) rather than a generic cutoff to determine d-dimer elevation in patients older than 50 years. Most faculty I asked stated that they would support use of age-adjusted d-dimers in PE algorithms, despite some doubts regarding population cohorts, gold standards, and variant assays. If you want to delve further into the potential problems and pitfalls of the d-dimer, Rory Spiegal MD, provides an interesting discussion of these in his blog

I consider some practices to be poor: for example, ordering d-dimers in triage. Typically, triage is not conducive to a thorough exam nor does it give time for accurate risk assessment; such profligate ordering might incite the wrath of your colleagues. I made this error myself as a new grad PA in triage. Lesson learned. If you see this, kindly put the kibosh on it. Furthermore, the d-dimer isn’t a lab you order and then fail to follow up. Just don’t do it. Indiscriminate use of the d-dimer jeopardizes the safety of your patient whereas judicious use protects your patient.

P5. Pictures

Step 5: Imaging studies. Patients with a positive d-dimer or high pre-test probability require imaging studies. The gold standard is the CTA PE. This test is not innocuous. It may detect subclinical PEs, result in contrast-induced nephropathy, cause allergies, and create a financial burden for the patient. However, in the high-risk patient, the CTA is the go-to test. VQ scanning is useful for patients with contraindications to CT but not for patients with CHF, COPD or pneumonia. Another valid strategy is to order venous duplex studies of the lower extremities prior to CT as this may eliminate the need for CT and obviate its inherent risks.

In conclusion, pernicious, petulant, and peculiar is as pernicious, petulant and peculiar does; yet by paying attention to the Ps of PE evaluation, you can improve outcomes, reduce cost, sharpen your skills as a diagnostician, and enjoy your own brand of P soup.

Reference

-

Douma RA et al. Prometheus Study Group. Performance of 4 clinical decision rules in the diagnostic management of acute pulmonary embolism: a prospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011; 154:7009.